| Author |

Message |

Chad Arnow

myArmoury Team

|

Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 11:00 am Post subject: Polearms before 1400 Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 11:00 am Post subject: Polearms before 1400 |

|

|

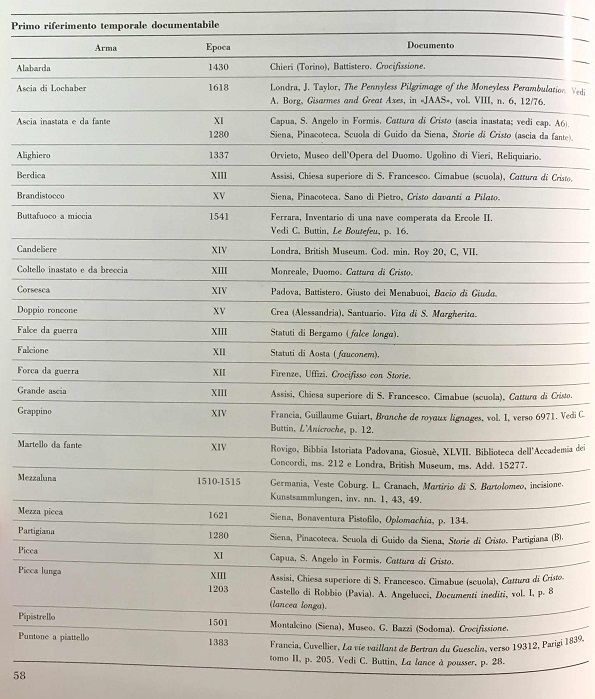

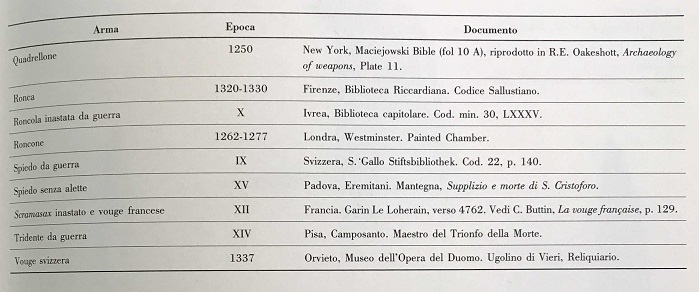

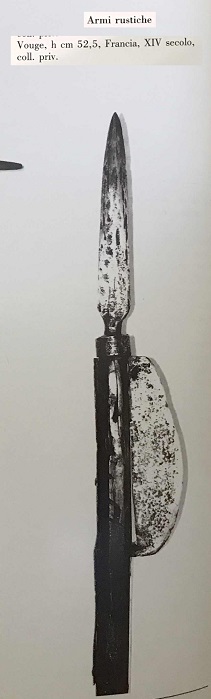

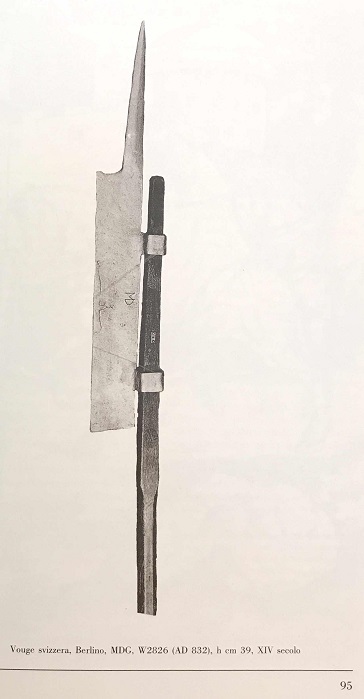

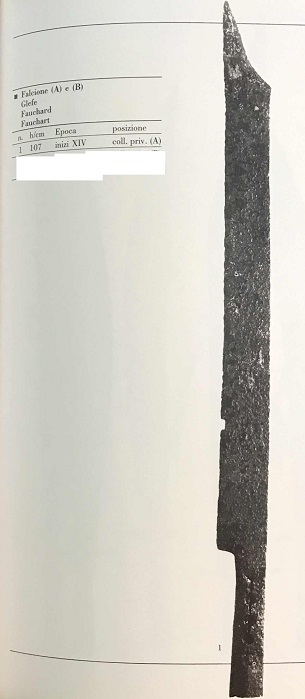

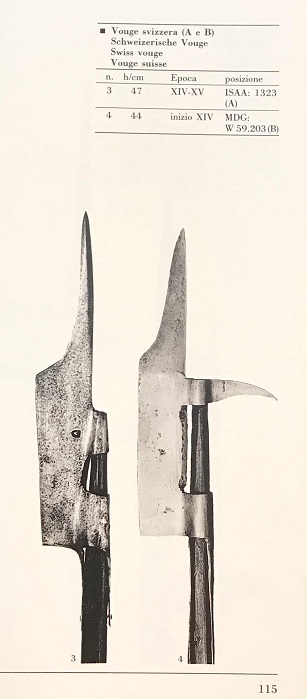

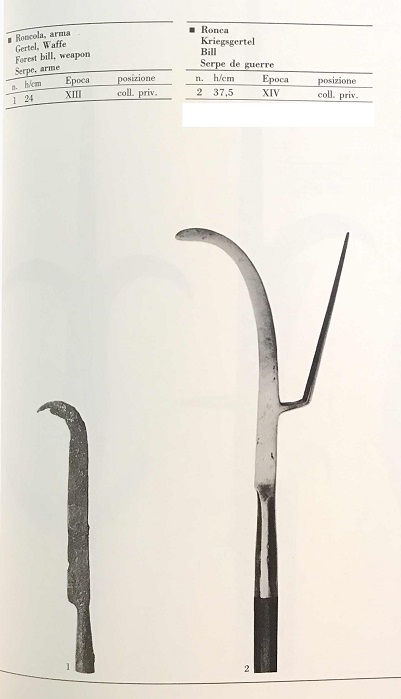

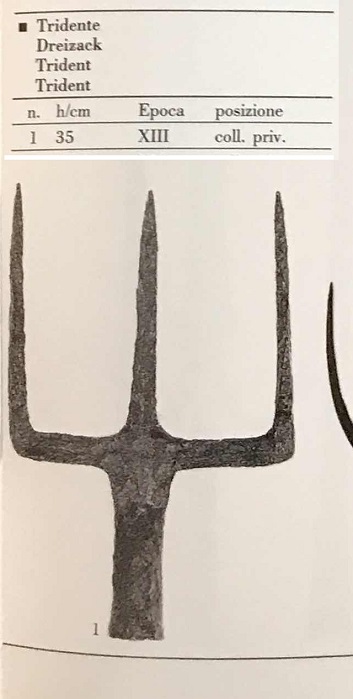

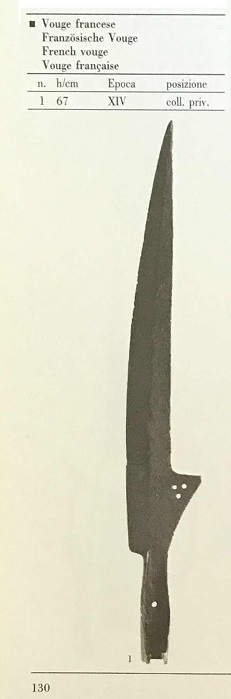

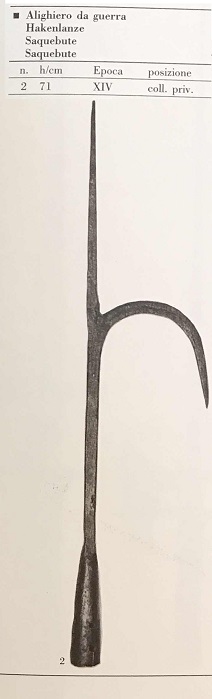

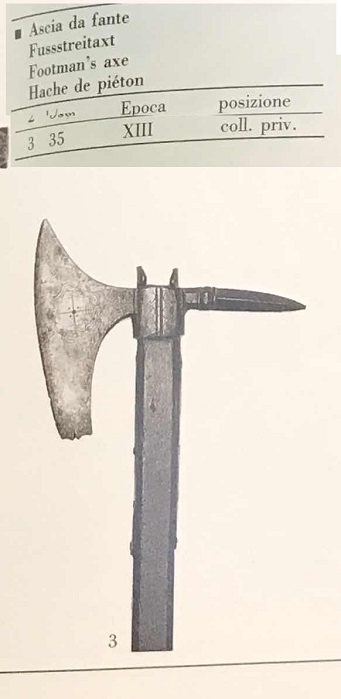

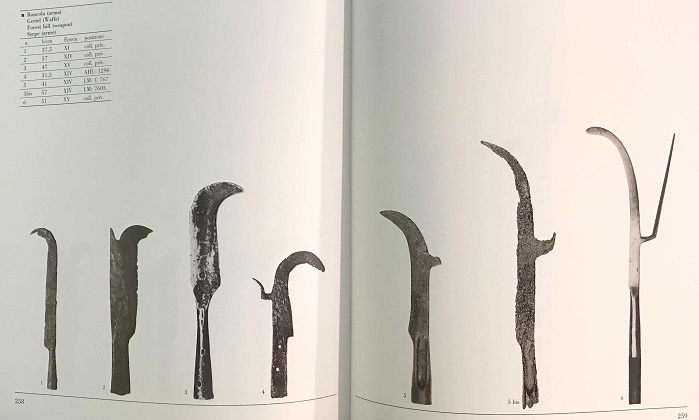

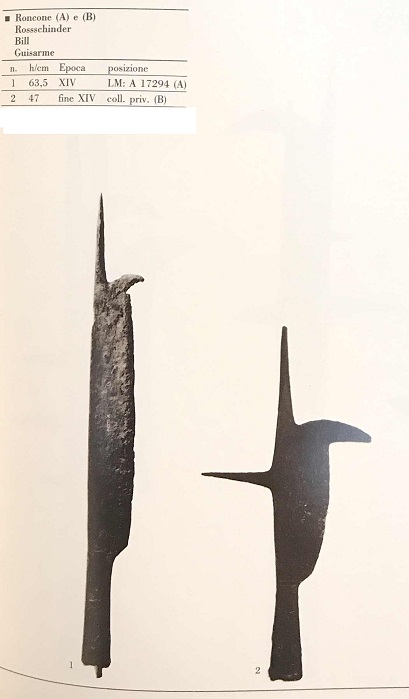

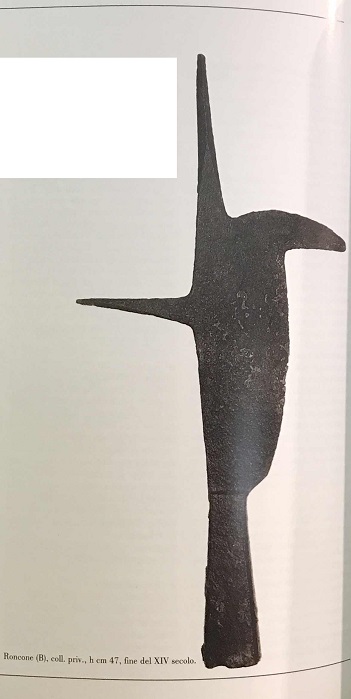

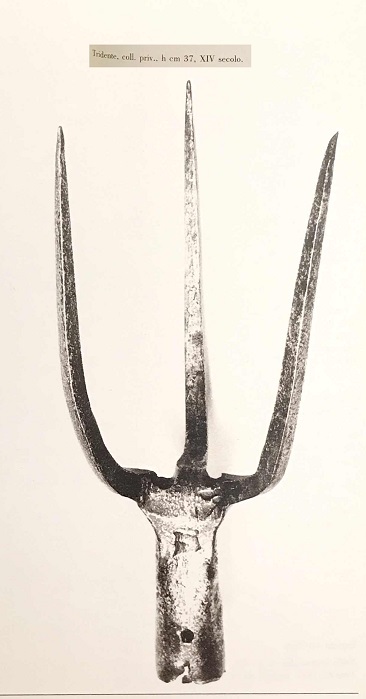

There are a number of threads on here asking about earlier polearms. There seems to be interest, but not a ton of info out there. From 1400 on, there are many examples that get talked about a lot; much less so from before 1400. Mario Troso's book "Le Armi in Asta delle Fanterie Europee 1000-1500" (roughly translated "Pole Weapons of European Infantry 1000-1500") is a treasure trove of info on pole arms and shows far more early examples than I've seen elsewhere. Apart from spears, of course, there were quite a few things in use before the 15th century. I'm attaching images from the book (which is out of print and hard to come by). First, the image quality isn't great. My scanner is slow and I didn't want to spend hours standing in front of it wearing out both my spine and the spine of a rare book. These are pictures from a tablet and are skewed in a variety of ways. I also edited out (poorly) captions/text/other weapons from outside the period. The book also contains a lot of period art from pre-1400, but I didn't take pics of those.

First up are some charts showing different types of polearms and dating associated with them. Really interesting to see when different forms appeared. Following that are early polearms. I left out the spears, as we're all pretty familiar with those.

Attachment: 173.23 KB Attachment: 173.23 KB

Attachment: 151.64 KB Attachment: 151.64 KB

Attachment: 75.18 KB Attachment: 75.18 KB

Attachment: 35.91 KB Attachment: 35.91 KB

Attachment: 43.95 KB Attachment: 43.95 KB

Attachment: 45.55 KB Attachment: 45.55 KB

Attachment: 49.69 KB Attachment: 49.69 KB

Attachment: 49.86 KB Attachment: 49.86 KB

Attachment: 54.14 KB Attachment: 54.14 KB

ChadA

http://chadarnow.com/

|

|

|

|

Chad Arnow

myArmoury Team

|

Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 11:05 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 11:05 am Post subject: |

|

|

And some more. There's a limit to what can be attached to each post...

As an FYI, "Secolo" is Italian for "century." Some captions/charts use "Epoca" (epoch, time, age, etc.) instead.

Attachment: 33.46 KB Attachment: 33.46 KB

Attachment: 29.17 KB Attachment: 29.17 KB

Attachment: 44.75 KB Attachment: 44.75 KB

Attachment: 43.19 KB Attachment: 43.19 KB

Attachment: 57.15 KB Attachment: 57.15 KB

Attachment: 48.18 KB Attachment: 48.18 KB

Attachment: 49.01 KB Attachment: 49.01 KB

Attachment: 51.64 KB Attachment: 51.64 KB

ChadA

http://chadarnow.com/

|

|

|

|

J. Nicolaysen

|

Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 3:01 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 3:01 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

Fantastic Chad, thanks. Another great-sounding but hard to find book. Really cool examples of polearms

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 8:15 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 8:15 am Post subject: |

|

|

Really neat and helpful, thanks for posting this!

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

Craig Peters

|

Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 12:18 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 12:18 am Post subject: |

|

|

If I might be permitted to add to the discussion:

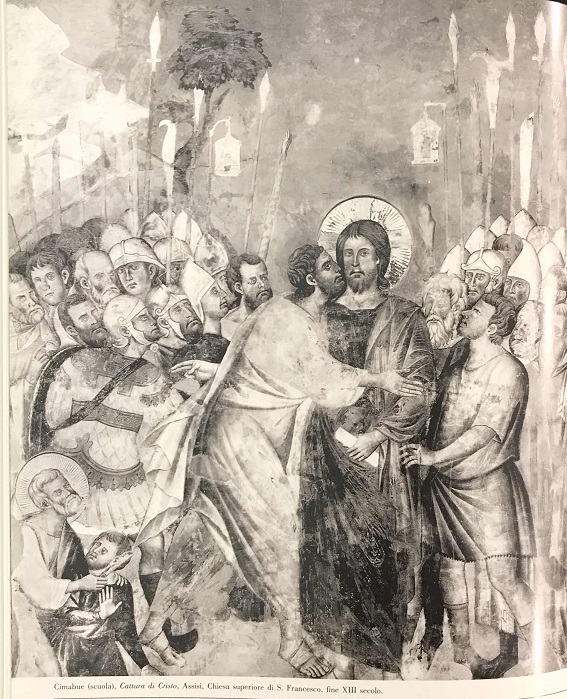

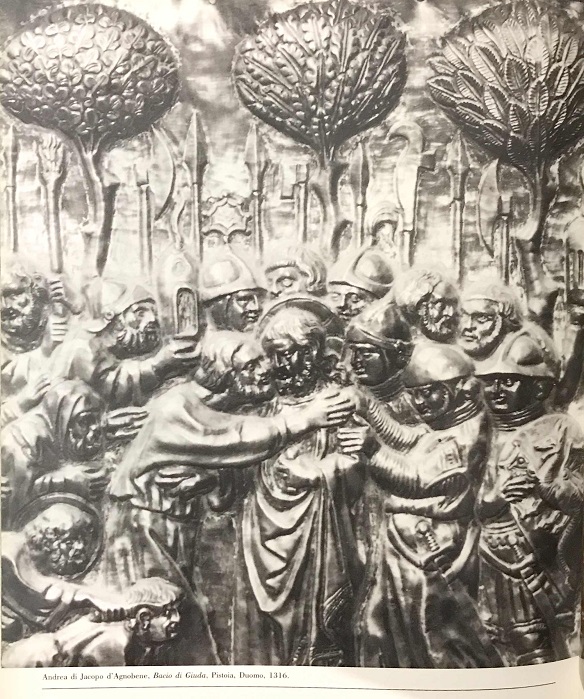

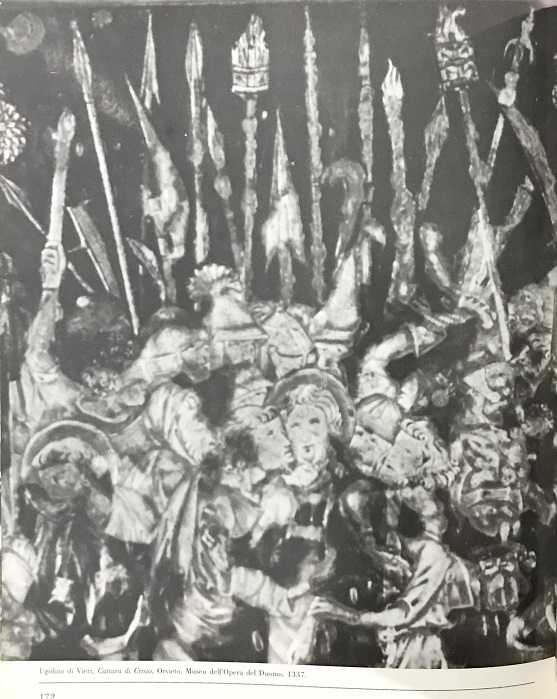

Period art is another area that can provide insight into early polearms. Of course, art has to be handled cautiously because it can sometimes be in a deliberately archaic style, or might exaggerate the appearance of weapons. Nevertheless, it can give some valuable insights into polearms beyond extant artifacts.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, the overwhelming majority of polearms are spears and lances. Miniature after miniature shows knights and infantry carrying them and fighting with them. Weapons other than swords and spears/lances are quite rare. There are a few instances of maces (primarily in Italian miniatures) and a few instances of axes. The latter are seen a bit more frequently in Western European art, including miniatures from France and England. Intriguingly, siege slings—slings attached to a haft and always shown when besieging a castle—are more common in art at this time than polearms which are not spears, lances and axes.

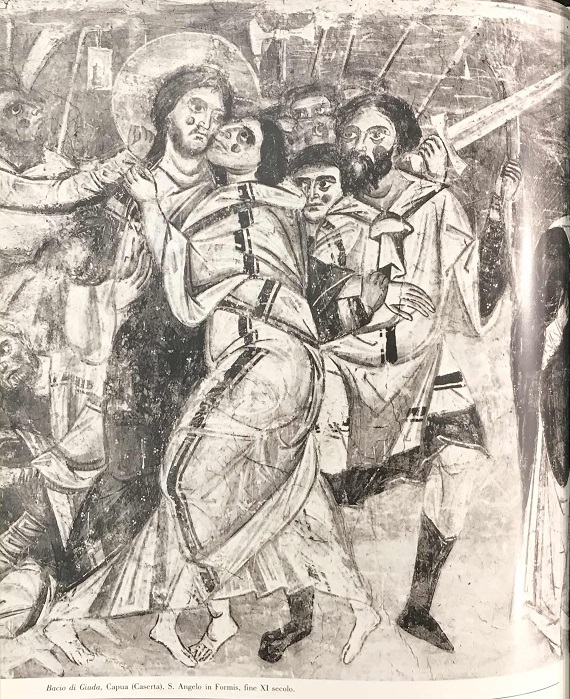

There is only one unambiguous instance in the collection from Manuscript Miniatures of an image depicting some other form of polearm. This is found in the 1136 AD Italian manuscript BNF NAL 710 Exultet, depicting the betrayal and arrest of Christ. Several soldiers carry weapons which are unambiguously examples of the forest bills seen in Chad's images. There also appears to be various maces, both with flanges and without. My impression is that these may be hafted and similar in length to the spears, making them more analagous to later morning stars. However, their exact length is uncertain, meaning there is insufficient evidence for the morning star claim. Noteworthy are also axes which do not correspond with the appearance of Danish/Viking axes more commonly seen in contemporary illustrations.

There is one other example I have found so far, a rather odd looking axe from the Morgan M.736 Miscellany on the life of St Edmund . It dates to 1130 AD. However, whether this axe is just an exaggerated depiction of a regular war axe or whether it should be classified as some other form of “polearm” is debatable.

There are two additional points worth drawing attention to. First, from a preliminary investigation of period art, the impression is that only in Italy would one find, very rarely, a polearm that was not a spear or lance during the 11th or 12th centuries. Secondly, it's worth considering the frequency of such polearm depictions. Arguably, they are under-attested in art. Nevertheless, to give a sense of perspective, 1 miniature out of 441 that are dated between 1100 AD and 1200 AD depicts a polearm aside from axes, spears/lances—and in this image, the only other polearms are the forest bills. This means that 0.002% of all 12th century miniatures depict polearms other than axes, spears and lances. To my knowledge, 0% of the 11th century miniatures depict other polearms.

Attachment: 80.47 KB Attachment: 80.47 KB

Attachment: 255.45 KB Attachment: 255.45 KB

[ Download ]

|

|

|

|

|

Matthew Amt

|

Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 2:03 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 2:03 am Post subject: |

|

|

I'm a little curious about the dating on some of these artifacts. I would have thought that the more slender bill-like weapons, particularly with that forward-angled backspike, were quite late. A couple of those bills are basically identical to a couple found in 17th century contexts in Jamestown and other sites in Virginia, though of course the colonists were sent a lot of outdated stuff.

It's all good stuff, just kinda wondering...

Matthew

|

|

|

|

Chad Arnow

myArmoury Team

|

Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 9:31 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 9:31 am Post subject: |

|

|

Matthew and Craig,

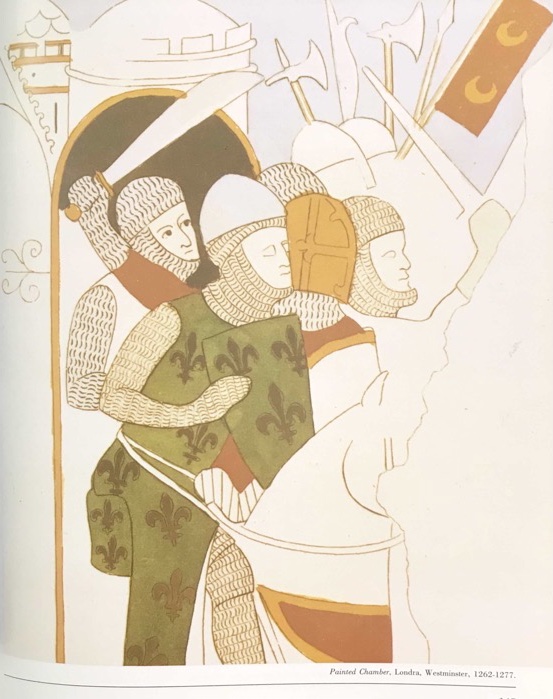

Thanks for chiming in. I'm a little skeptical of the dating of some of the surviving examples as well. However, the charts I posted above (especially the 2nd and 3rd images in the first post) show the first verifiable date for each of the forms. Many of those are datable period art. While I think it's safe to say they were more common later, I think we can say they did exist.

Craig, thanks for the math on search results from Manuscript Miniatures. It's certainly compelling. They do have a lot of things, though not everything, and search terms are tagged by humans.

I wasn't planning on taking pics of the period art from the book, but Craig's and Matthew's comments inspired me.  These are the bits of period art Troso included from the period 1000-1400. I left out things after 1400 and things showing the spears we already know about. There are at least a couple whose dates I might be skeptical of, but I'm not an art historian.... These are the bits of period art Troso included from the period 1000-1400. I left out things after 1400 and things showing the spears we already know about. There are at least a couple whose dates I might be skeptical of, but I'm not an art historian....

Attachment: 232.66 KB Attachment: 232.66 KB

Attachment: 179.76 KB Attachment: 179.76 KB

Attachment: 284.15 KB Attachment: 284.15 KB

Attachment: 147.15 KB Attachment: 147.15 KB

Attachment: 198.13 KB Attachment: 198.13 KB

Attachment: 211.8 KB Attachment: 211.8 KB

Attachment: 204.45 KB Attachment: 204.45 KB

Attachment: 194.57 KB Attachment: 194.57 KB

Attachment: 150.85 KB Attachment: 150.85 KB

ChadA

http://chadarnow.com/

|

|

|

|

|

Matthew Amt

|

Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 2:03 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 2:03 pm Post subject: |

|

|

OH! Okay, call me a believer! Thanks, Chad, great stuff!

Matthew

|

|

|

|

Craig Peters

|

Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 9:01 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 9:01 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Regarding my search protocol, I was aware that depending upon other people to tag miniatures with the word “polearm” could lead to me missing some relevant images. Therefore, I did a manual search of Manuscript Miniatures, with the time frame of 1000-1200 AD.

I found one other image from Armour in Art. It's another Arrest of Christ, dated 1100-1199 AD, from the Chapelle de Notre-Dame d'Yron, Cloyes-sur-la-Loire, France. What is most notable is the fact that several of the soldiers are holding glaives. See here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/biron-philippe/6329396329/sizes/l/in/pool-530819@N20/

From what I can see of the four images we have from the 11th and 12th centuries, we have examples of what might be termed a “war scythe” (assuming it is hafted), glaives and forest bills. These all date to the 12th century, while the 11th century example seems to depict an unusual war axe or “axe polearm” of some sort.

What is curious is that every one of these images is a depiction of Christ being arrested. None are conventional illustrations of armed conflicts between knights and other soldiers. I wonder then to what extent these images are depicting genuine military weapons as opposed to makeshift peasant/commoner weapons that are essentially modified farm tools. The billhooks are not far off in appearance from modern bills, while the sickle looks very much like a farming implement. As for the glaives, the fact they are being carried by soldiers gives the impression they are genuine military polearms. With the other polearms that are not spears or axes, it is less clear.

|

|

|

|

|

Pieter B.

|

Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 10:04 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 10:04 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Could it be that polearms were a response to late 12th century changes in cavalry warfare?

I believe the last decades of the 12th century and the first of the 13th century marked something of a change in that regard. Milites started fighting on horseback more often, as argued by Strickland, and jousts first became popular. It is not entirely uncontested but I believe the couched lance also supplanted other methods of lance use. In response to more common and more intense cavalry combat we see early developments like larger areas of the body covered by mail, smaller shields and enclosed helmets followed later in the 13th century by early plate armor. Soldiers on foot seem to have been blessed with composite crossbows, kettlehelmets and gambesons around the same time.

Other contemporary regions in which cavalry warfare was important such as Song Dynasty China or Japan also seem to have had a thing for polearms.

|

|

|

|

Craig Peters

|

Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 11:42 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 11 Aug, 2022 11:42 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Pieter,

My guess, which is mostly educated speculation, is that the development in polearms is specifically related to developments in armour—not just technological developments, but also armour becoming increasingly affordable. Whether or not this is specifically linked to an increasing emphasis upon cavalry in the late 12th and early 13th century is less clear. In England and France at least, cavalry provided an important element of warfare throughout the 12th century. I am unaware of an increase in its importance later in the century. My impression also is that some other parts of Europe were increasingly influenced by England and France, such as lowland Scotland during the reign of David I and Malcolm IV, and the Holy Roman Empire under Frederick Barbarossa. These regions would therefore have already had a strong influence from cavalry well before the close of the 12th century.

It seems reasonable to suggest that polearms become increasingly common as infantry begins to have better access to armour, especially to mail hauberks and chausses. Wielding a polearm other than a spear represents a significant sacrifice to defense because you are forced to employ two hands. For much of the 11th and 12th century, when infantry might only have a helmet and shield, or shield alone, a spear would be the only sensible polearm to use. However, once mail armour becomes comparatively more affordable, and eventually brigandine also, then the sacrifice for wielding a polearm starts to make a little more sense. I think it's telling that the great profusion of polearms takes place after circa 1400, precisely around the time when it starts to become more common even for infantry to wear breastplates and partial plate armour.

|

|

|

|

Craig Peters

|

Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 12:09 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 12:09 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

Another thought: during the 11th and 12th centuries, spears are a much better choice of polearm than other forms because of how well they work in formations. As I'm sure you know, wielding spears allows infantry to be in comparatively dense formations which is useful against cavalry or other infantry- a definite advantage over other polearms which require more room to wield unless you employ them like a spear. Further, if the infantry has limited defenses in the form of shields, or even no defense at all, a densely-packed spear formation is safer for the infantry due to the layering of spears forming a sort of “hedge”. Other polearms do not offer this advantage unless you use them as a spear, and even then, you sacrifice the defense of a shield. As a formation weapon, spears are probably better than nearly every other form of polearm, especially when your defenses are limited.

|

|

|

|

Bartek Strojek

|

Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 12:28 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 12:28 am Post subject: |

|

|

The fact that all those polearm depictions appear in one scene, and one of key events of Christianity itself too, does suggest that the power of convention might have been huge here.

Many of those polearms look blurry and off, as if artist wasn't exactly sure what was he drawing. But it was obviously right thing to draw, after all, all those painting of such important event couldn't have been wrong.

|

|

|

|

|

Anthony Clipsom

Location: YORKSHIRE, UK Joined: 27 Jul 2009

Posts: 361

|

Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 1:32 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 1:32 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Bartek Strojek wrote: | The fact that all those polearm depictions appear in one scene, and one of key events of Christianity itself too, does suggest that the power of convention might have been huge here.

Many of those polearms look blurry and off, as if artist wasn't exactly sure what was he drawing. But it was obviously right thing to draw, after all, all those painting of such important event couldn't have been wrong. |

It's a long lived convention too - Durer followed it in the 16th century, for instance. One thing to note is an air of the exotic or foreign, because of the context. Perhaps more relevant is a sense of a mob of lower orders, or perhaps the watch, rather than the weapons of milites or professionals.

Anthony Clipsom

|

|

|

|

Chad Arnow

myArmoury Team

|

Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 11:14 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 11:14 am Post subject: |

|

|

I realized I overcropped the Westminster image. Here it is with less cropping…

Attachment: 122.57 KB Attachment: 122.57 KB

ChadA

http://chadarnow.com/

|

|

|

|

Chad Arnow

myArmoury Team

|

Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 12:53 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 12:53 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Craig Peters wrote: | | Regarding my search protocol, I was aware that depending upon other people to tag miniatures with the word “polearm” could lead to me missing some relevant images. Therefore, I did a manual search of Manuscript Miniatures, with the time frame of 1000-1200 AD. |

Craig,

Thanks for doing all that.  That’s a lot of work…. That’s a lot of work….

ChadA

http://chadarnow.com/

|

|

|

|

Craig Peters

|

Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 4:40 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 12 Aug, 2022 4:40 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Hi Bart,

If I've understood you correctly, your argument is that the artists are likely drawing based upon conventions. As such, there is not good evidence to suggest the weapons they depict were actually in use at the time.

On the one hand, there is an argument to be made about following “convention”. If the artists depicted details actually following the details of Christ's arrest, they are following a “convention” so to speak. The three synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) all agree that the people who came to arrest Jesus were carrying “clubs and swords”. John's gospel is vaguer in terms of what arms were carried. It simply identifies the men were carrying “weapons” and “lanterns and torches”. Beyond this, all four gospels record one of the disciples drawing a sword and striking the servant of the high priest, though only in the Gospel of John is Peter explicitly identified as the one having done so. Therefore, any medieval illustration that contains the above-mentioned elements is following “conventions” in terms of depicting the scene. Notice, however, that the only weapons explicitly named are “swords and clubs”. Any other weapons represent artistic choices, rather than Biblical record.

You have mentioned that many of the polearms look blurry and off, presumably reflecting that the artist had not seen them. However, if you spend plenty of time looking at manuscript art and medieval frescoes, it will become apparent that plenty of medieval art suffers from being comparatively poor quality. There are plenty of instances where parts of the illustration lack sharpness and precision, even when depicting common and well-known weapons like swords and spears/lances. Also, plenty of medieval art has declined in quality due to aging or other mishaps experienced by the manuscript. These factors do not, in and of themselves, demonstrate the artists had no knowledge of the weapons.

Lastly, one still might argue that there does come to be an established set of artistic conventions which artists follow, borrowing from past precedent. That may be true perhaps during the 13th and 14th centuries—but looking carefully at the images Chad posted, you see as much variation in the scene as you see continuity. For the time period I am focusing upon specifically, the 11th and 12th centuries, the argument for an established artistic convention seems particularly weak. There may be plenty of other images of Christ's arrest that we have not seen that could lend support to a convention. In the four images we have looked at, there is not particularly consistent overlap. Nearly all agree about axes and spears. Some have what could be morning stars, but what may be clubs and maces. Two have glaives that look very different in style (unless you want to identify them as being two different weapons, which reinforces the lack of similarity in the two images), while one has a war sickle and a different image has forest bills. The only polearm that is common to all four is the spear, which shouldn't be surprising given how ubiquitous they were during the Middle Ages. A fairly strong argument can be made for axes, if we count them as a polearm, as three of the four images unambiguously depict them. Beyond that, however, there is no clear tradition or convention for other polearms. The very specific appearance of the glaives and bills, and the fact they cannot easily be copied from other contemporary art because so few examples exist, suggests the artists were basing their illustrations upon actual weapons they had encountered or at least knew of well, rather than drawing from conventions.

In my view, the artistic evidence overall supports the contention that these weapons were actually found at the time when the art was produced, albeit rarely.

|

|

|

|

Chad Arnow

myArmoury Team

|

Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 3:34 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 3:34 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I took a quick minute tonight to compare some of Troso's info with George Snook's short monograph "The Halberd and Other European Polearms 1300-1650." Troso puts the Halberd ("Alabarda" in the charts above) as a 15th century item with an earliest dating of 1430 from a piece of art. Snook, however, notes a poem by Konrad of Wurzburg from before 1287 that mentions halberds. Snook goes on to note that the earliest datable halberd is from 1315, recovered from the battlefield at Morgarten. He doesn't show a picture of it...

Confusing things is that what Snook might call an early (Swiss) halberd Troso calls a "Vouge Svizzera" ("Swiss Volgue"). Even so, if Snook's example from 1315 is a Swiss halberd/voulge and not a true "halberd," that moves Troso's dating for the Swiss Volgue back from 1337 to 1315. Snook's contention (grossly simplified) is that axes got bigger/evolved into what some call Swiss Halberds (Troso: Volgue), then into the halberds of the 15th century and beyond.

Snook offers this chronology of the halberd in the 13th and 14th centuries:

13th Century:

-Early prototype is essentially a two eyed axe

-At end of century: Blade long and thin, slightly curved and comes to a point

-Spear [top spike] not well defined

-Eyes are square, later becoming round

-Small beak between eyes or integral with upper eye

-Blade secured by nail in either the lower or both eyes

14th century:

-Upper eye may be smaller than lower eye

-Upper edge of blade elongates and indents to form a true spear [top spike]

-Head becomes larger and heavier and more rectangular

-Beak becomes integral with head

-Eyes merge to become a socket

-Axis of spear is in front of shaft

-Spear is short and sharpened on both edges. May have reinforced points

-Rudimentary langets integral with small socket appear

ChadA

http://chadarnow.com/

|

|

|

|

|

Len Parker

|

|

|

|

Craig Peters

|

Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 7:29 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 7:29 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I had a look at manuscript art again. This time, I have not searched exhaustively through the images by date. Rather, my search was with the tags “axe” and “halberd” (including some of the other European variant spellings of “halberd”).

As Chad's discussion has noted, part of the problem is how one defines a “halberd”. I cannot provide a definitive solution to this problem. For the purposes of my search, I will define a halberd as follows: it has an axe head, some sort of back fluke or spike, and a top that has been sharpened to a point, especially if the top appears to be metal.

During the 13th century, we find an immense variety of axes. Some are single handed, some two. Some clearly look like a continuation of the large Danish Type M war axes (the classic, late Viking axe) while others look more like Type L axes. Others have much smaller heads, and are similar to Type A and Type B axes. Some don't seem to exactly fall within existing axe typologies. Some of these axes have a back spike, while others do not.

However, overall, there seems to be little 13th century evidence for halberds as I have defined them. In fact, Chad's image of the Westminster painting of 1262-1277 AD is the only one that I have seen so far depicting what could be termed a “halberd”.

The next image I have located with a halberd is the Queen Mary Psalter of circa 1310-1320 AD. After that is an image of the “sleeping guards” before Christ's tomb in the Taymouth Hours of 1325-1350 AD. The first non-British example I have seen is from the Czech Velislavova Bible, circa 1325-1349. Thereafter there appear to b examples in France and elsewhere in Europe. By circa 1350, it seems that halberds have started to become reasonably common in European art.

Attachment: 90.5 KB Attachment: 90.5 KB

Attachment: 102.36 KB Attachment: 102.36 KB

Attachment: 132.39 KB Attachment: 132.39 KB

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2026 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|