| Author |

Message |

Pedro Paulo Gaião

|

Posted: Sat 09 Apr, 2016 12:14 pm Post subject: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats Posted: Sat 09 Apr, 2016 12:14 pm Post subject: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats |

|

|

I'm come with an increasing interest in the forms of the so called "transitional armour" (i.e. armored surcoats, coat-of-plates and cloth-globose brestplates). However, I have some extremely pertinent questions which I did not find answers anywhere else, I hope you can help me guys.

First of all: The earliest's reference of an armored surcoat dates from St. Maurice's effigy (1250), present in an germany's cathedral. We have the written record of the same armor also dating from 1250, the scandinavian's "Konungs skuggsj". Latter, we find another wrriten document called "Hirdskraa", from 1270s' Scandinavia.

My question is: why there aren't no archaeological evidence for this kind of armor? It has to do with the low popularity of it? Perhaps low quality or low efficiency?

Why there is only one thirteenth century's effigy representing the armoured surcoat, but there aren't any others? I mean, for a reinforcement of this type be mentioned in written sources and effigies it assumed that they were at least popular in the local places where they were mentioned / represented. But why there are no references to armored surcoats (or "Plata", according to "Hirdskraa") outside North-Germany and Scandinavia? Is there a cultural factor in the middle of it all?

I saw one of Graham Turner's illustration of 1290's Acre were a Teutonic knight wears an armoured surcoat. It's likely that these armours were at Outremer at this times, even among german crusaders?

What do you think of the theory which claims that this type of equipment has been inspired by the armor that Mongols brought in their invasions to Europe at 1240's? My main problem with it parts of the point that the only references of it does not come from Hungary or Poland, but Germany and Scandinavia, which did not come into contact with the Mongols.

Okay, the main question: how they played heraldry in these types of surcoats? Whenever I see reconstructions of this type of equipment (to speak the truth of any transitorial armor itself) they never put a coats-at-arms on it. Even in pictures of Graham Turner, like this:

Medieval people ever put something heraldry in this type of clothing? Also, this picture also caught my attention, it should represent the King St. Louis of France:

I particularly don't know who made it and I suspect also that should represent something that St. Lous wore in his crusade, but this was even possible? I mean, he's using the german plate innovations (shynbalds) and, especially, an armoured surcoat with the coat-of-arms of France. What is your opinion about this?

|

|

|

|

|

Alex W.

Location: Canada, Alberta Joined: 16 Feb 2016

Posts: 10

|

Posted: Sat 09 Apr, 2016 7:01 pm Post subject: Posted: Sat 09 Apr, 2016 7:01 pm Post subject: |

|

|

My answer to the first question: because there are barely any archeological remnants of any armour from this period left. there are only two coat of plates finds that I know of; Wisby and Kussnacht.

To the second question, it may be because it was only used rarely, if at all. Maybe only by the absurdly wealthy. Keep in mind, that the idea was in it's infancy at this point, and that the plates don't even overlap, providing extremely limited thrust protection.

I've heard more often that it was introduced to the crusaders in the holy land. I have done very little research on the matter, so have no opinion.

As for heraldry, I would assume they would have simply put heraldry on normally, we only have two effigies that show the armour, so it's very, very shaky ground to draw too many assumptions from, but I would assume they would apply their arms to whatever was the outermost layer.

My focus is more the mid 14th century, so I am mostly working from what I have heard others say and everything should be taken with a grain of salt.

|

|

|

|

|

Mart Shearer

|

Posted: Sat 09 Apr, 2016 9:16 pm Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats Posted: Sat 09 Apr, 2016 9:16 pm Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats |

|

|

| Pedro Paulo Gaião wrote: | First of all: The earliest's reference of an armored surcoat dates from St. Maurice's effigy (1250), present in an germany's cathedral. We have the written record of the same armor also dating from 1250, the scandinavian's "Konungs skuggsj". Latter, we find another wrriten document called "Hirdskraa", from 1270s' Scandinavia.

My question is: why there aren't no archaeological evidence for this kind of armor? It has to do with the low popularity of it? Perhaps low quality or low efficiency? |

As noted above, any survival of armor from the 13th century is rare. We're not sure of the Magdeburg statue's age. Although c. 1250 is frequently cited, it could be decades more modern. The King's Mirror calls for the breastplate or plates (brjóstbjörg) to be worn over the aketon (panzara) and beneath the mail, so you can't see it at all. A similar worked iron plate (ferro fabricata patena) is worn beneath the mail in Guillaume le Breton's Philippidos, Book III, line 497 of c.1215-1220, and another example of a single breastplate (Gehôrte vür die brust ein blat) worn with gambeson and hauberk appears in Heinrich von dem Türlin's Diu Crône from the 1220s. At that early date, these seem to be hidden, single plates designed to stop lance strikes to the chest.

| Quote: | | Why there is only one thirteenth century's effigy representing the armoured surcoat, but there aren't any others? |

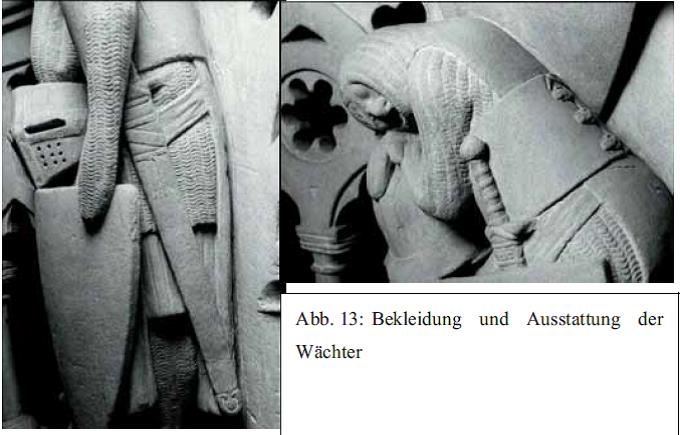

Other 13th century depictions include: the "sleeping guard" from Kloster Wienhausen, c.1280-1290 -

http://www.monasticmatrix.org/figurae/wienhau...ist-statue

Another "sleeping guard" at the Konstanz Rundkapelle, 1260-1280:

http://www.bildindex.de/bilder/mi01850a03a.jpg

Another early depiction appears in the Italian Cappella di San Martino, Assisi, 1312-1317:

http://armourinart.com/24/29/

And the Løgumkloster St. Maurice in Denmark, 1300-1325:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:L%C3%B...rein_4.jpg

| Quote: | | I saw one of Graham Turner's illustration of 1290's Acre were a Teutonic knight wears an armoured surcoat. It's likely that these armours were at Outremer at this times, even among german crusaders? |

Since there is evidence for these early pairs of plates with skirts dating from before 1290 in Germany, it is reasonable to conclude that is a possibility.

| Quote: | | What do you think of the theory which claims that this type of equipment has been inspired by the armor that Mongols brought in their invasions to Europe at 1240's? My main problem with it parts of the point that the only references of it does not come from Hungary or Poland, but Germany and Scandinavia, which did not come into contact with the Mongols. |

The Mongols used a very similar armor, with plates riveted inside a cover. German troops participated in the alliance facing the Mongols at the Battle of Legnica (Liegnitz) in 1241, and assembled and repelled several minor raids after the defeat of the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohi. Correlation is not proof of causation, but should be considered as one possible explanation.

| Quote: | | Okay, the main question: how they played heraldry in these types of surcoats? Whenever I see reconstructions of this type of equipment (to speak the truth of any transitorial armor itself) they never put a coats-at-arms on it. |

Remember that not all surcoats display heraldry, either.

http://manuscriptminiatures.com/4832/7932/

However, the 1302 inventory of Raoul de Nesle, Constable of France who was killed at the Battle of Courtrai provides some positive evidence:

Item unes plates vermeilles vil.

Item, a (pair of) plates, vermillion. 6 livre.

Item unes autres plates des armes de Neele iiiil.

Item, one other plates with the arms of Nesle. 4 l.

Although it is a century after the pairs of plates first appear, the 1357 Inventory of arms for William of Bavaria, Count of Hainaut also has a pair of plates with an heraldic shield on it.

Premiers, ij paires de plattes de wière, s'en sont les unes couviertes d'un drap d'or et les autres d'un bleu velluiel à j escut des armez Monsigneur le conte Willaume.

To begin, 2 pairs of plates of war, of which one is covered with cloth of gold, and the other one blue velvet with 1 escutcheon with the arms of my lord the count William.

Another interesting early figure shows a small cross on this Templar figure, (if the white is meant to be a pair of plates.)

Attachment: 121 KB Attachment: 121 KB

'Expositio in Apocalypsim', Cambridge MS Mm.5.31, fo.139r, Bremen, 1249-1250

ferrum ferro acuitur et homo exacuit faciem amici sui

|

|

|

|

|

Mario M.

|

Posted: Sun 10 Apr, 2016 5:15 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 10 Apr, 2016 5:15 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Alex W. wrote: | | and that the plates don't even overlap, providing extremely limited thrust protection. |

Excuse me but how does that statement make any sense?

The plates are connected to each other, and even if they were not, that still leaves most of the surface area of the torso covered by those plates.

The reasonably authentic reproduction tested by Mike Loades in the documentary "Weapons that made Britain: Armour" stopped cavalry lance strikes, only the most powerful ones went through, and when they did, they barely went through.

Also, I completely disagree with the notion of the coat of plates being an introduction through the Middle East/Asia.

You cannot use eastern lamellar as an example of earlier coat of plates, the construction is completely different.

We have more sources mentioning Middle Easterners buying Western gear than vice versa.

“The stream of Time, irresistible, ever moving, carries off and bears away all things that come to birth and plunges them into utter darkness...Nevertheless, the science of History is a great bulwark against this stream of Time; in a way it checks this irresistible flood, it holds in a tight grasp whatever it can seize floating on the surface and will not allow it to slip away into the depths of Oblivion." - Anna Comnena

|

|

|

|

Pedro Paulo Gaião

|

Posted: Sun 10 Apr, 2016 11:22 am Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats Posted: Sun 10 Apr, 2016 11:22 am Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats |

|

|

| Mart Shearer wrote: | | The King's Mirror calls for the breastplate or plates (brjóstbjörg) to be worn over the aketon (panzara) and beneath the mail, so you can't see it at all. A similar worked iron plate (ferro fabricata patena) is worn beneath the mail in Guillaume le Breton's Philippidos, Book III, line 497 of c.1215-1220, and another example of a single breastplate (Gehôrte vür die brust ein blat) worn with gambeson and hauberk appears in Heinrich von dem Türlin's Diu Crône from the 1220s. |

Quite curious. For it points out that these iron plates probably begun as reinforcements stitched or riveted in padded gambersons worn beneath mail armour, already at early 13th! Guillaume le Breton ever mentions how common this was in France? By that I mean: how relatively developed was the usage of these gamberson/surcoat reinforcements at that time in France, at least? It was used only by the king and his close noblemen or was something more "popular", like its usage among french counts and so?

If we consider that this type of armor had some kind of popularity by the more western kingdoms (ie, France) and that we have record of similar reinforcements still in 1250s' Scandinavia, we could say that St Maurice 's effigy probably points to a more innovator torso's reinforcement, where iron plates would be riveted into surcoats? It seems reasonable ...

| Mart Shearer wrote: | | and another example of a single breastplate (Gehôrte vür die brust ein blat) worn with gambeson and hauberk appears in Heinrich von dem Türlin's Diu Crône from the 1220s. |

Any idea how it could be the appearance of something like this?

The knight at the right seens to wore a very similar style to what Graham Turner made to a so called english knight:

This has the format similar to the style found in effigy of St. Maurice, I think. But I haven't' found the retangular plate format and the rivets that should be represented on it.

I'm sure that I already saw this plate's pattern in one of Visby findings. The Knyght Errant, in his series on the later forms of coat-of-plates, mentions that the armors found in Visby represent something that would use some decades before (perhaps because the latest models have been looted at the end of the battle), but I wouldn't think that would be four decades! If we have such frescos in Italy, I think we can speculate about some local production of these armours at 1310s.

Last edited by Pedro Paulo Gaião on Sun 10 Apr, 2016 5:47 pm; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

Dan Howard

|

Posted: Sun 10 Apr, 2016 2:06 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 10 Apr, 2016 2:06 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Mario M. wrote: | | Alex W. wrote: | | and that the plates don't even overlap, providing extremely limited thrust protection. |

Excuse me but how does that statement make any sense?. |

Pretty much all of the evidence we have for scale, lamellar, COPs, corrazinas, armoured jacks, and brigandines have overlapping plates. There are exceptions but not many. Armours made from non-overlapping plates seem to primarily be the province of Hollywood costume departments. If you wanted to attempt to make a reconstruction of one of the armours depicted in the illustrations then it should incorporate overlapping plates.

Author: Bronze Age Military Equipment, Pen and Sword Books

|

|

|

|

Pedro Paulo Gaião

|

Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 9:32 am Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 9:32 am Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats |

|

|

I dind't asked before, but:

| Mart Shearer wrote: | | The King's Mirror calls for the breastplate or plates (brjóstbjörg) to be worn over the aketon (panzara) and beneath the mail, so you can't see it at all. A similar worked iron plate (ferro fabricata patena) is worn beneath the mail in Guillaume le Breton's Philippidos, Book III, line 497 of c.1215-1220, and another example of a single breastplate (Gehôrte vür die brust ein blat) worn with gambeson and hauberk appears in Heinrich von dem Türlin's Diu Crône from the 1220s. |

They were riveted on the gamberson (in such way that the iron pieces would be visible on the surface of the gamberson itself) or they were riveted between the layers a separated piece of cloth (which wouldn't be the gamberson itself), and the cloth would, then, be placed beneath the mail armour?

I've been looking for this effigy and I ended up finding a picture of Ian Heath's drawing:

http://www.warfare.altervista.org/WRG/Feudal-...-c1280.htm

He mentions that:

| Quote: | | Coats-of-plates are first mentioned in two Italian documents, a war-order of Florence (1259/60) and a mercenary contract from Massa, near Carrara (1267) both referring to the armour of German knights in the service of these cities. In addition the new fangled ‘plate’ armour worn by German mercenaries at the Battle of Benevento in 1266 could only be coats-of-plates, and all the earliest sculptures, etc, depicting coats-of-plates are apparently of German origin. Bengt Thordeman, the excavator of Wisby, therfore concludes that this type of armour was probably introduced into Europe via Germany by the Mongols, though no contemporary sources seem to describe such armour in use amongst the latter. Interestingly, however, 13c depicts a very broad type of ‘belt’ of Polish origin which there is good reason to believe may be the forerunner of the coat-of-plates, consisting of several layers of leather, sometimes reinforced, and buckled at front or back. It appears to have evolved in Poland as early as the beginning of the 12th century, this particular example being from a ms. of c.1100. It seems more than probable, therefore, that the Germans adopted this form of armour during their campaigns against the Poles, improving on it until they arrived at the ‘coat-of-plates’ in the mid-13th century. |

I found one of the records of these battles in another forums' topic on Early Greatswords, about the Battle of Benevento (1266):

| Ewart Oakeshott wrote: |

Gallant and knightly, but ridiculous, Manfred's army was a heterogenous melange of assorted mercenaries (who could be relied upon to fight as long as they were paid) and his own barons and their feudal levies, who (as Manfred knew) could be relied upon to run away or change sides as soon as threr was an opportunity.

About half of these mercenaries were Sicilian Sarascens, some infantry armed with bows and with no real defensive armour, the rest light cavalry. The better part were some 1200 German men-at-arms, large, heavy, well-trained, disciplined warriors on big horses armed with long war swords (Type XIIIA's, which we met before) and well armoured with the new reinforcements of plate over their mail.

Manfred sent his light Saracen bowmen out first as skirmishers to harass the French; then the rest of his army followed in three divisions. First came the 1200 Germans, followed by a second division of 1000 Italian mercenaries. He led the rear "battle" himself, composed of the rest of his faithful Saracens combined with the untrustworthy barons of the Regno with their followers.

The French could hardly believe their eyes when they saw this. Manfred had handed Charles the battle, and his kingdom, on a plate. What followed is hardly worth describing except for one thing which is the whole point of this long tale. Charles' men were very worn out, starving and well outnumbered, but in spite of Manfred's idiocy, they very nearly lost the battle after all-because those heavily armoured Germans, with their great swords, seemed to be impervious to the utmost that the French and Provencal knights could do to them. They began to mow their opponents down, keeping knee to knee together and steadily forcing their way forward, hewing down all in front of them. Then somebody noticed that when they lifted their arms to strike, a more or less unprotected place appeared under their arms. All the chroniclers who wrote of this battle emphasise that the French were armed with swords quite different from those of the Germans, shorter and more accutely pointed. The knight who noticed the weak, unarmoured place under the Germans' arms yelled out "a l'Estoc!, a l'Estoc!" "Use the point!" And they did, thrusting their sharp little swords into the Germans' chests. Very soon, their solid formation began to break up...

The significance, for our purpose here, of this absurd, nasty battle which affected the whole history of Europe for another two centuries-to our own day, if it comes to that-is that here in use, vividly described by eye-witnesses, are the two types of sword which I have called XIIIA, the "Grant Espee d'Allemagne", and the shorter, lighter, swifter, pointed one I've called Types XIV and XV. A very interesting point here is that we find the Germans clad in the very latest kind of armour, yet using older offensive weapons, while the French, clad in outmoded mail, used a much more up-to-date and effective weapon of offense... |

Last edited by Pedro Paulo Gaião on Mon 11 Apr, 2016 9:41 am; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

Pedro Paulo Gaião

|

Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 9:38 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 9:38 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Mart Shearer wrote: | | Quote: | | Okay, the main question: how they played heraldry in these types of surcoats? Whenever I see reconstructions of this type of equipment (to speak the truth of any transitorial armor itself) they never put a coats-at-arms on it. |

Remember that not all surcoats display heraldry, either.

http://manuscriptminiatures.com/4832/7932/ |

That I did not know. I thought that the main reason behind the popularity of surcoats was the representation of one's coat-of-arms, whether to you be identified in combat or whether to you be recognized during the counting of the dead. The usage of surcoats without arms was common at 13th century? By the way, this picture should represent a swiss knight, right?

| Mart Shearer wrote: | However, the 1302 inventory of Raoul de Nesle, Constable of France who was killed at the Battle of Courtrai provides some positive evidence:

Item unes plates vermeilles vil.

Item, a (pair of) plates, vermillion. 6 livre.

Item unes autres plates des armes de Neele iiiil.

Item, one other plates with the arms of Nesle. 4 l.

Although it is a century after the pairs of plates first appear, the 1357 Inventory of arms for William of Bavaria, Count of Hainaut also has a pair of plates with an heraldic shield on it.

Premiers, ij paires de plattes de wière, s'en sont les unes couviertes d'un drap d'or et les autres d'un bleu velluiel à j escut des armez Monsigneur le conte Willaume.

To begin, 2 pairs of plates of war, of which one is covered with cloth of gold, and the other one blue velvet with 1 escutcheon with the arms of my lord the count William. |

I noticed the use of the term "pair of plates," which seems to be an equivalent of "coat of plates"- like armor. In which period this term was used? And why "a pair of"? Means that were only two pieces of cloth which would be buckled together?

Do you have any specific site that has records of these inventories? Can be useful for my research ...

-----------

| Mario M. wrote: | Also, I completely disagree with the notion of the coat of plates being an introduction through the Middle East/Asia.

You cannot use eastern lamellar as an example of earlier coat of plates, the construction is completely different.

We have more sources mentioning Middle Easterners buying Western gear than vice versa. |

The theory does not necessarily refer to lamellar, but what Mongols called "Khatangu Degel", a Chinese armor worn only by imperial guards which had riveted pieces of iron on a silk clothing. The Mongols liked it so much that had popularized it among their cavalry after China's conquest.

|

|

|

|

|

Mart Shearer

|

Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 10:54 am Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 10:54 am Post subject: Re: Coat of Arms in Armoured Surcoats |

|

|

| Pedro Paulo Gaião wrote: | I dind't asked before, but:

| Mart Shearer wrote: | | The King's Mirror calls for the breastplate or plates (brjóstbjörg) to be worn over the aketon (panzara) and beneath the mail, so you can't see it at all. A similar worked iron plate (ferro fabricata patena) is worn beneath the mail in Guillaume le Breton's Philippidos, Book III, line 497 of c.1215-1220, and another example of a single breastplate (Gehôrte vür die brust ein blat) worn with gambeson and hauberk appears in Heinrich von dem Türlin's Diu Crône from the 1220s. |

They were riveted on the gamberson (in such way that the iron pieces would be visible on the surface of the gamberson itself) or they were riveted between the layers a separated piece of cloth (which wouldn't be the gamberson itself), and the cloth would, then, be placed beneath the mail armour? |

Unfortunately, the literary descriptions don't always give us that much detail. In Diu Crône the plate in front of the breast is mentioned after the gambeson, hauberk, and coif, but before the surcoat, so it might have been worn over the mail. In Philippidos a lance penetrates shield boss, shield, gambeson and hauberk before being stopped by the plate, so it is worn beneath the mail, like in the Konungs-skuggsjá. The 1311 Inventory of John fitz Marmaduke, Lord of Horden has a possible plate attached to the aketon:

j gaimbeson cum alleccys liij s. iiij d.

1 gambeson with protector, 53s. 4d.

| Quote: | | I found one of the records of these battles in another forums' topic on Early Greatswords, about the Battle of Benevento (1266): |

You must be careful when considering second-hand descriptions. We have previously discussed this passage on this forum before.

| Mart Shearer wrote: | | Dan Howard wrote: | | We don't need a translation of the whole battle - just the few passages in which armour is mentioned. |

This is the famous call to use the point, "l'estoc". France mentions the use of the knife and stabbing at Bouvines, and then this rebuttal is found while discussing the Battle of Benevento (bolding mine). The orginal source would seem to be Andrew (III) of Hungary.

John France, Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades, 1000-1300, Chapter 13, Note 24:

| Quote: | | The tactic of stabbing under the armpit recurs in Primatus's account of the Battle of Tagliacozzo of 1268, and Delbruck, Medieval Warfare, pp. 353-7, criticized the notion as the invention of a later writer on the basis of soldiers' tales, but Delbruck did not know the sources himself: in particular, he did not know that the story is found in Andrew of Hungary, and was relying on the studies of others. Oman, Art of War, vol. 1, pp. 502-3, studied the battle of Benevento at length and supposed that this tactic was designed to avoid German plate armour. Runciman, Sicilian Vespers, pp. 109-11, follows Oman and repeats this myth. However, there is no mention of plate-armour at Benevento: the accounts stress the close order of the Germans. |

|

ferrum ferro acuitur et homo exacuit faciem amici sui

|

|

|

|

|

Mart Shearer

|

Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 11:15 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 11:15 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Pedro Paulo Gaião wrote: | I noticed the use of the term "pair of plates," which seems to be an equivalent of "coat of plates"- like armor. In which period this term was used? And why "a pair of"? Means that were only two pieces of cloth which would be buckled together?

Do you have any specific site that has records of these inventories? Can be useful for my research ... |

Pair used to mean a set, not just two. Rosaries were described as a pair of beads, staircases as a pair of stairs, etc.. Some single items composed of matched sets are still called pairs in English: a pair of scissors, a pair of pants.

Pair of plates, or often simply plates is the most common descriptor for the armor made of plates riveted to a covering of textile or leather in European inventories. Coat of plates (often abbreviated on forums as CoP) is the modern phrase for the same armor. Thom Richardson of the British Royal Armouries suggests the modern use arises from a misreading of primary accounts.

| Thom Richardson wrote: | The cerothes or cerotheca were gauntlets forming part of early plate harness

for war. The multi-plate examples excavated from Wisby probably illustrate the

type represented in Fleet’s account. Only four fragments of these defences are known

to survive, one certainly from London and another, illustrated here, probably from an

English provenance (figure 9). The word cerothes is usually contracted to cothes

de platis, and the incorrect reading of this may be the origin of the modern term

coat of plates for what is invariably called a pair of plates in the documents. |

I've tried my hand at translating a few of these inventories into English on Armour Archive. You can click any one for the armor references and a link to the originl document. There are others to be added, of course.

http://forums.armourarchive.org/phpBB3/search...mit=Search

ferrum ferro acuitur et homo exacuit faciem amici sui

|

|

|

|

Dan Howard

|

Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 1:51 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 11 Apr, 2016 1:51 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Pedro Paulo Gaião wrote: | | That I did not know. I thought that the main reason behind the popularity of surcoats was the representation of one's coat-of-arms, whether to you be identified in combat or whether to you be recognized during the counting of the dead. |

What little evidence we have suggests that the surcoat was adopted to protect armour from the rain.

| Quote: | He mentions that:

Quote:

Coats-of-plates are first mentioned in two Italian documents, a war-order of Florence (1259/60) and a mercenary contract from Massa, near Carrara (1267) both referring to the armour of German knights in the service of these cities. In addition the new fangled ‘plate’ armour worn by German mercenaries at the Battle of Benevento in 1266 could only be coats-of-plates |

As Mart already said, there is no evidence for any kind of 'new fangled' armour at Benevento. It is not a good idea to rely on Osprey for your research. Most of their books are not very good.

Author: Bronze Age Military Equipment, Pen and Sword Books

|

|

|

|

Pedro Paulo Gaião

|

Posted: Tue 12 Apr, 2016 6:40 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 12 Apr, 2016 6:40 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Mart Shearer wrote: |

You must be careful when considering second-hand descriptions. We have previously discussed this passage on this forum before.

| Mart Shearer wrote: | | Dan Howard wrote: | | We don't need a translation of the whole battle - just the few passages in which armour is mentioned. |

This is the famous call to use the point, "l'estoc". France mentions the use of the knife and stabbing at Bouvines, and then this rebuttal is found while discussing the Battle of Benevento (bolding mine). The orginal source would seem to be Andrew (III) of Hungary.

John France, Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades, 1000-1300, Chapter 13, Note 24:

| Quote: | | The tactic of stabbing under the armpit recurs in Primatus's account of the Battle of Tagliacozzo of 1268, and Delbruck, Medieval Warfare, pp. 353-7, criticized the notion as the invention of a later writer on the basis of soldiers' tales, but Delbruck did not know the sources himself: in particular, he did not know that the story is found in Andrew of Hungary, and was relying on the studies of others. Oman, Art of War, vol. 1, pp. 502-3, studied the battle of Benevento at length and supposed that this tactic was designed to avoid German plate armour. Runciman, Sicilian Vespers, pp. 109-11, follows Oman and repeats this myth. However, there is no mention of plate-armour at Benevento: the accounts stress the close order of the Germans. |

|

|

Based on what was shown, I really have to agree about the attack armpit technique is a Runciman's myth, but I disagree that there was no form of plates in battle. I get those notes on "Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades 1000-1300" at Google Books and found this:

What John France mentions in his notes is that they hadn't articulated plates in the battle of time,(i.e. white plate armor from 1415-1420), but he assumes that there were plates pieces underneath the mail. It is true that this is hardly the armoured surcoat/pair of plates we're talking about, since it was placed over of the mail. But he accepts at least the earlier 13th's iron pieces that you showed in scandinavian and french sources. Still, I continue defending the idea that used iron plates in their surcoats because in this arrangement the details (rivets and plate shapes over the surcoats) would be visible to observers (as I suspect were the chroniclers of battles) that mention some sort of these.

| Mart Shearer wrote: | I've tried my hand at translating a few of these inventories into English on Armour Archive. You can click any one for the armor references and a link to the originl document. There are others to be added, of course.

http://forums.armourarchive.org/phpBB3/search...mit=Search |

Thank you, will be of great use to me

-----------------

| Dan Howard wrote: | | Pedro Paulo Gaião wrote: | | That I did not know. I thought that the main reason behind the popularity of surcoats was the representation of one's coat-of-arms, whether to you be identified in combat or whether to you be recognized during the counting of the dead. |

What little evidence we have suggests that the surcoat was adopted to protect armour from the rain. |

True, when analyzing medieval illustrations of battles is very uncommon to find knights who have their surcoats with their coats-of-arms. But, why we couldn't interpret this as an illustrators' attempt to save time in their drawings? I actually noticed such "trend" when I saw an battle's illustration where an entire group of cavalry is mounted on two horses only! (it even turned into meme on the internet)

It makes little sense to represent all those unknown knights and barons with their coats-of-arms. It would complicate and even pollute the illustration. Of course, I'm not saying that knights and some barons wouldn't wore simple collored surcoats, but I doubt about how common it was (at Agincourt the englishmen slayed an important nobleman because they don't identified anyone important based on his tabard).

| Dan Howard' wrote: | | As Mart already said, there is no evidence for any kind of 'new fangled' armour at Benevento. It is not a good idea to rely on Osprey for your research. Most of their books are not very good. |

Although Ian Heath is the author of several Osprey's books, this figure / text itself is his own book called "Armies of Feudal Europe 1066-1300"

|

|

|

|

|

Håvard Kongsrud

|

Posted: Fri 15 Apr, 2016 1:32 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 15 Apr, 2016 1:32 pm Post subject: |

|

|

A few minor notes.

The use of coat of plates in the Norse (Norwegian) hirdskrá (royal household law) pertains only to the higest ranks, from Skutilsvein (ridder, knight) and up.

The three coat of plates-clad guards sleeping at the ressurection of christ in the Mauritz rotunda in Konstanz has been redated from around 1280 to ca 1260. The date often given at ca 1260-80 is simply a combination of the two. See Stephan Bussmann 2001, Das Heilige Grab in Konstanz, diplomoppgave kunsthistorie, der Fachhochschule Köln. The statues have traces of polychromy (having been painted) Here's another image of the thre men.

Mathias Goll suggested in his 2013 thesis a later dating of the coat of plates-clad st maurice statue in Magdeburg on the basis of his study of transitional armour. However, his argument makes no consessions to the art-historians researching the statue for the last century comparing the statue with the other statues at the site. And until their theories are discussed, their mid century date stands. The same goes for other martial historians' attempts at re-dating it.

|

|

|

|

|

Mart Shearer

|

Posted: Fri 15 Apr, 2016 2:32 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 15 Apr, 2016 2:32 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Håvard Kongsrud wrote: | | The three coat of plates-clad guards sleeping at the ressurection of christ in the Mauritz rotunda in Konstanz has been redated from around 1280 to ca 1260. The date often given at ca 1260-80 is simply a combination of the two. See Stephan Bussmann 2001, Das Heilige Grab in Konstanz, diplomoppgave kunsthistorie, der Fachhochschule Köln. The statues have traces of polychromy (having been painted) |

It is often forgotten that most medieval statues were originally painted, and a great deal of the detail such as rivet heads can be lost with the paint. At least it he gives a good picture of the back.

Attachment: 46.16 KB Attachment: 46.16 KB

ferrum ferro acuitur et homo exacuit faciem amici sui

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2026 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|