English Swords 1600-1650

An article by John F. Hayward

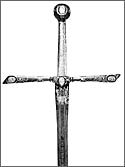

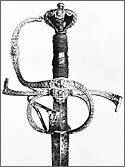

Fig. 1 a&b—Front and back view of the hilt of a back-sword, its whole surface damascened with arabesques in gold. Late 16th/early 17th century. (Private Collection, Scotland)

|

This account of English swords of the reigns of Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603), James I (r. 1603-1625) and Charles I (r. 1625-49) starts at the very end of the Elizabethan period, as it is not possible to identify earlier specimens with any certainty. There is no lack of evidence showing the various hilt fashions favored by English noblemen during the 16th century, for a great many portraits survive depicting them with their hands proudly resting on their sword hilts. Many of these swords must also survive somewhere, but unfortunately they do not differ in any essential detail from those in contemporary Continental portraits and therefore cannot be identified as English.

This account of English swords of the reigns of Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603), James I (r. 1603-1625) and Charles I (r. 1625-49) starts at the very end of the Elizabethan period, as it is not possible to identify earlier specimens with any certainty. There is no lack of evidence showing the various hilt fashions favored by English noblemen during the 16th century, for a great many portraits survive depicting them with their hands proudly resting on their sword hilts. Many of these swords must also survive somewhere, but unfortunately they do not differ in any essential detail from those in contemporary Continental portraits and therefore cannot be identified as English.

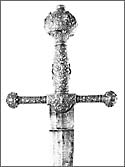

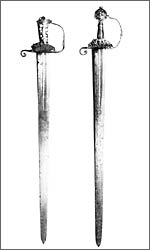

Fig. 2—Backsword with incised hilt damascened with silver, pierced pommel, and signed blade; about 1630-40. (Burrell Collection, Scotland)

|

There are, it is true, a few Holbein designs for sword hilts that were made either for Henry VIII or the young Prince Edward, later Edward VI, but these were intended to be executed in gold and are of exceptional elaboration and costliness.1 They do not, therefore, bear much relevance to the typical English sword hilt of the mid-century—that is, if an English type did exist at all at that period. We must therefore begin at the end of the Elizabethan period, though the types described may have been known a decade or so earlier. No dated hilts are recorded, but by about 1600 no fewer than four different hilt types existed, all of which can be seen in contemporary English portraits and may be recognized with some degree of confidence as English. This does not necessarily mean that all swords fitted with one or another of these hilt types must be English. Many of them are now to be seen in Continental museums and collections; some may have been purchased in England at the time, some may have been presented to foreign visitors either at the time or subsequently, and others again may have been wrought abroad by special order in the English manner.

While the hilts are not dated, some of the blades do bear a date etched or engraved on them, including those illustrated here in Figs. 5 and 8. The presence of a date on a blade cannot be accepted as conclusive evidence of the date of the hilt it accompanies. A new hilt may have been fitted to an old blade or vice-versa in the 16th or 17th centuries; alternatively, the blade may have been changed by a collector in the course of the last hundred and fifty years-that is, in the period in which old swords have been collector items.

Four Basic Types

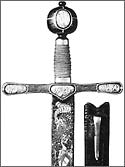

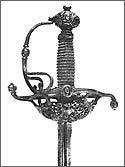

Fig. 3—Backsword, the hilt encrusted with silver floral scrolls; first quarter 17th century. (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

|

The types of swords here to be considered are: (1) backswords, (2) broadswords, (3) riding swords and rapiers, and (4) hangers or hunting swords. While it is possible to trace the development within each type, one cannot say which if any, had priority.

Backswords

The Elizabethan backsword has a hilt of simple construction (Figs, la and b), with straight, usually counter-curved quillons, knuckle-bow and ring-guard on one or on both sides of the cross. This simple construction persisted for a long time and is still found on a backsword with a Hounslow blade in the Burrell Collection, Glasgow (Fig. 2). A more evolved type of hilt is shown in Fig. 3. This has the heavy globular or octagonal pommel that is one of the characteristic features of late 16th or early 17th century swords made in England. The quillons are counter-curved, and the hilt has fully developed arms, knuckle-bow and a loop guard reaching from halfway along the bow down to join the rear arm. This particular construction was not confined to backswords but will be found on rapiers and riding swords as well.

Broadswords

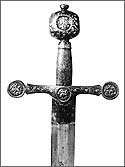

The typical broadsword had a basket hilt, but a somewhat earlier example is shown in Fig. 4. In this case the blade must once have been of considerable weight but repeated grinding has reduced it to a shadow of its former self. The shell, which is divided into two halves, one on either side of the cross, is another feature that

Fig. 4—Broadsword, the hilt chiselled with profile heads in relief, incised and damascened with gold; about 1600. (Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh)

|

will frequently be noticed on English swords. The English basket hilt, which is, of course, the ancestor of the Scottish basket-hilted sword of the 17th and 18th centuries, was, if the dates on portraits showing it can be believed, already in existence before the last quarter of the 16th century. A portrait of Sir Edward Lyttleton at Hagley in Worcestershire dated 1568 shows him with one of these basket-hilted swords with long counter-curved quillons. The earlier examples can be recognized by the presence of the long quillons, while the later ones have only a rear quillon and have developed the two loops at the base of the basket in front (Fig. 5), characteristic of the later Scottish versions of this hilt. The two hilts illustrated both have the large globular pommel but of rather flatter form than that found on the backsword or rapier hilts. That in Fig. 6 can be dated approximately, as it belonged to Sir William Twysden of Roydon Hall, Kent, who was created a knight by James I in 1603 and a Baronet in 1611. The blade of the sword in Fig. 5 is dated 1611 and is one of a number by Clemens Horn of Solingen bearing the same date.

Fig. 5—Broadsword, the basket hilt encrusted with silver, the blade etched and gilt, signed and dated 1611. (Private Collection, London)

|

A second type of broadsword had a simple cross hilt; many samples of this particular type survive, a high proportion of them in Continental collections. Thus there are examples in the Hermitage, Leningrad, in the Tøjhusmuseum, Copenhagen, the Swedish Royal Armoury, Stockholm and the Swiss Landesmuseum, Zurich.

There are two versions of these cross-hilts, differing in decoration rather than in form. In the one type the ornament is of silver or gold and silver encrustation in the iron of the hilt, while in the other thin medallions of silver, embossed or stamped with figure subjects, are inset in the hilt and the surrounding areas are either damascened with gold or encrusted with silver. The finest of all these swords is that illustrated in Fig. 7: this was made for Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, and the eldest son of James I. The blade is decorated with the Prince of Wales's feathers and the sword can, therefore, be dated between 1610, when Henry was created Prince of Wales, and his death in 1612. The blade is further damascened in gold with the monogram PH of the Prince and signed "CLEMENS HORN ME FECIT SOLINGEN." The Prince of Wales's sword appears to have lost its original grip; this was probably of iron damascened en suite with the rest of the hilt. The sword at Leningrad, which has a hilt of comparable richness to the Prince's sword, retains the original grip (Fig. 8). In this case the silver encrustation differs in many details from the established English patterns and its origin is not certainly English, though like so many of the fine English swords, it also has a Clemens Horn blade, dated, as is that of the basket-hilted broadsword in Fig. 5, 1611. Horn must have received an important order for blades from an English sword-cutler, for, in addition to the three mentioned above, there is the blade in The Victoria and Albert Museum,

Fig. 6—Broadsword, the basket hilt encrusted with silver, formerly belonging to Sir WIlliam Twysden of Roydon Hall, Kent; first quarter of 17th century. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

|

Fig. 13—Sword of State of the City of Canterbury, the cross set with silver panels embossed with panels of gold damascening within silver lines. The blade etched and gilt with inscriptions referring to King James I. Acquired by the City of Canterbury, Kent, in 1607.

|

which is etched and gilt with the Royal Stuart arms, and two swords in the English Royal Armoury at Windsor Castle, which are believed to have belonged to James I and Prince Charles (later King Charles I) respectively. A less richly decorated version of this cross-hilted type is illustrated in Fig. 9. The finest of the second type of cross-hilt is that in the Swiss Landesmuseum (Fig. 11). The hilt is set on each side with four shaped silver plaques embossed in low relief with scenes from the Passion of Christ while the surrounding areas are damascened with gold. The blade is exceptional in that it is of Persian origin. Of somewhat earlier date than the hilt, it was re-mounted when the hilt was made. Three other hilts, preserved in Copenhagen and Stockholm respectively, are of closely similar design: the silver inserts, all circular in form, are embossed in low relief with a group of St. George killing the dragon. Similar swords are to be seen in portraits of Knights of the Order of the Garter, and in view of the very similar design of these three hilts, together with the presence of the badge of the Order, it seems possible that they also were intended to accompany the regalia of the Garter which were sent to the King of Denmark and Sweden by James 1 and Charles I respectively.2 (Figs. 10 and 12)

One further cross-hilted sword remains to be mentioned; this is the sword of state of the City of Canterbury (Fig. 13). It is an enlarged version of the second type, the pommel and cross being set on each side with four silver plaques, now much damaged, one of which appears to represent Judith with the head of Holophernes. As in the case of the swords described above, the remaining area is damascened with silver lines enclosing areas of gold arabesques. The blade is damascened on one side with the arms of the city and on the other with the Stuart royal arms further inscribed "THIS SOVRDE WAS GRAUNTED BY OUR GRATIOUS SOVERAIGNE LORD KING IEAMES TO THE CITY OF CANTERBURY" and on the other with an extract from the law of Moses. The sword was acquired in 1607 and its cost is recorded in the accounts of the city for that year as 41/-. The silver grip engraved with royal arms and that of the city together with roses and thistles is a later substitution and dates from the reign of Charles I or II.

Fig. 7—Cross-hilted sword of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, the hilt encrusted with silver including profile heads of Roman Emperors, the blade damascened in gold; about 1610. (Wallace Collection, London)

|

Fig. 8—Cross-hilted sword, the hilt profusely encrusted with silver, signed 1611. (The Hermitage Museum, Leningrad)

|

Fig. 9—Cross-hilted sword, the hilt encrusted with silver, the blade signed "FERARA"; first third of 17th century. (Tøjhusmuseum, Copenhagen)

|

Fig. 10—Hilt is set with silver panels chased with St. George and the Dragon and damascened with gold scrollwork enclosing panels of silver encrustation; first third of 17th century. (Tøjhusmuseum, Copenhagen)

|

Fig. 11—Cross and pommel set with silver plaques stamped with scenes from the Passion of Christ, the intervening panels damascened with gold scrollwork. Earlier Persian blade. Perhaps made in England for export. (Schwelzerisches Landesmuseum, Zürchich)

|

Fig. 12—This hilt is set with silver panels embossed with St. George and the Dragon, the remainder of the hilt damascened with silver; first third of the 17th century. (Tøjhusmuseum, Copenhagen)

|

Riding Swords

The next two types, namely riding swords and rapiers, can be dealt with together as their hilts do not differ, the distinction lying in the weight of the blades. The earlier type of hilt has either straight of counter-curved quillons, knuckle-bow, and arms with a single loop reaching from the knuckle-bow to the rear arm while a short guard projects at right angles from the front arm. There are two or three counter-guards behind. Examples are shown in Figs. 14 and 15. These two hilts are richly damascened with silver lines enclosing panels of gold arabesques, but plainer versions (Fig. 16), some even undecorated, are known. During the second quarter of the century a distinctive type of cup-hilted rapier makes its appearance. In this the large globular pommel is abandoned in favor of an ovoid (Fig. 18) or lobate one (Fig. 17). The cup was either composed of two up-turned shells (Fig. 18) or it was a true cup pierced with a simple repeating pattern (Fig. 19).

Fig. 14—Riding sword, the hilt set with silver and damascened with gold mauresques within silver borders, one of the finest of the extant English swords of the early 17th century. Said to have been presented by Queen Elizabeth to a member of the Wetherby family.

(Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

|

Fig. 15—Rapier, the swept hilt encrusted with panels of silver masks and scrolls surrounded by gold damascening; first quarter 17th century.

(Wallace Collection, London)

|

Fig. 16—Riding sword, the hilt encrusted with silver, the blade with the probably surious signature "ANTONIO PICINIO"; first quarter of 17th century. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

|

Fig. 17—Cup-hilted rapier, the hilt with double-shell cup encrusted with silver, the blade signed "TOMAS AIALA IN TOLEDO 1610". (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

|

Fig. 18—Cup-hilted rapier, the hilt constructed of two shells and concentric rings, second quarter of 17th century. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

|

Fig. 19—Cup-hilted rapier, the hilt encrusted with silver, now much worn, second quarter of the 17th century. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

|

Fig. 20—Rapier: pierced pommel, chiselled with trophies of arms and masks, gilded. Perhaps English, early 17th century. (Wallace Collection)

|

Hunting Swords or Hangers

The last type to be mentioned is that of the hunting sword or hanger; a great many of these survived, all conforming closely to the pattern of the two illustrated in Figs. 21 and 22.

Gold and Silver Embellishments

Figs. 21 & 22—Two hunting swords, both decorated with silver encrustation in the same workshop; first half of the 17th century. (Messrs. Sotheby's, London)

|

A feature of some of the English swords discussed above is the excellence of the encrusting and damascening in gold and silver. The quality does, however, vary considerably, ranging from the cross-hilted sword of Henry, Price of Wales (Fig. 7) down t the backsword in Fig. 2. Earlier writers on the subject have of course, noted this difference and they have tended to ascribe only the coarser pieces to English masters, while giving the finer ones to Italian craftsmen. Thus Laking in his Catalogue of the Windsor Armoury describes two of the finest of them (nos. 60 and 61) as "of English fashion, but probably of Italian workmanship". They are, in fact, both quite typically English hilts, and the decoration was doubtless carried out in England, though whether by a native or an immigrant master there is no means of determining. Even as recently as 1962, in the second edition of the Wallace Collection Catalog, thee of these English swords, including that here illustrated in Fig. 15, are described as German, but for the insufficient reason that the blades are of German or, in one case, of Italian origin. Until the establishment of the Hounslow factory, the vast majority of English swords has imported blades and would, according to this system of classification, not rank as English. The presence of several of these finely decorated hilts in foreign collections, including two riding swords in the Dresden Historisches Museum and the three cross-hilted ones in Copenhagen and Stockholm respectively, has led to their being regarded by some writers as Continental; but the few examples recorded abroad are greatly outnumbered by those in old, established English collections, such as that at Warwick Castle. One is shown in Grose's Treatise on Antient Armour that was published as long as 1786.3

While English swords can be identified with some certainty by reference to their hilt construction, their ornament is a less reliable indication. Damascening in gold and encrustation with silver were forms of decoration that were applied in most western European countries, and the details-cherub's heads, floral scrolls, trophies of arms, etc-were also in general use. While some of the very simply decorated silver-encrusted hilts can be recognized as English by reference to the silver-work, the more difficult it is to establish their origin. Some of the craftsmen who executed the damascening in English may themselves have been immigrants and followed there the style and technique they had learned elsewhere. The cross-hilt shown in Fig. 9 could be of English or Continental origin.

The most striking feature of the decoration on the Prince of Wale's sword (Fig. 7) and on that in the Hermitage (Fig. 8) is the high relief and fine chasing of the silver, in particular the profile heads copied from classical medals. Next in quality to these two cross-hilted swords comes the broadsword of Sir William Twysden and the two hangers illustrated in Figs. 6, 21, and 22. On these the decoration is less crowded but at the same time executed in somewhat lower relief. Another type of decoration on the English hilts combined panels of minute gold damascening with silver encrustation. This is found on a good many English swords, though the damascening is rarely in such good condition as is that of the fine rapier illustration in Fig. 15. Some earlier swords, including the backsword in Fig. 1 were decorated exclusively with fine gold damascene that once covered the whole surface. The most pleasing of these hilts, which combine silver encrustation with gold damascene, is a sword formerly in the Spitzer and now in a Danish collection.4 The English origin of this sword, which was not recognized when it was in the Spitzer collection, is beyond doubt, and it is one of the finest surviving examples of the Elizabethan sword-cutler's art. It has a cup hilt upon which the ornament is arranged in alternate panels of silver and gold that run spirally. An offence committed by a member of the Cutlers' Company, which is referred to in a minute dated November 26, 1607, gives an insight into other methods of decorating sword-hilts. A certain William Oldren-shawe was accused of selling for sixteen shillings at Sturbridge Fair a rapier and dagger described as 'plain silvered'. As, however, he received no earnest money and another customer then appeared, he sold the same goods to him "with warranty it was hatched" for twenty-six shillings and eight pence. It was proved to the Court that the silver was not applied to the hilt by the process of hatching, -which called for a greater expense of silver as well as of labor-and the offender was accordingly fined. In 1632 a silvered sword was taken from another member of the Company, who promised not to repeat the offence. He had presumably tried to pass off a plated hilt as a solid silver one. A more common offence was the use of brass and copper for sword hilts instead of iron. In November 1635 the Court of the Cutlers' Company agreed to use their best endeavors "to suppresse and vtterly abandon the worcking and Tryming vp of swords, Rapiers and Skyrnes with Brasse and Copper Hilts and Pummels wch are Cast in moulds or any such deceiptfull way." Further, in September 1639, "Certeyne hilts handles and Pummels of Cast Brasse" which had been offered for sale "for sufficient worck made of Iron" were defaced by order of the Court.

Pierced Pommels and Guards

The various hilt types described above were exclusively English; another type which was fashionable in early 17th century England cannot be claimed as a purely English phenomenon. Its main feature is the fact that the pommel is pierced. The most important of these swords from our present point of view is one in the Windsor Castle Armoury, which, according to a reasonably convincing tradition, belonged to James I.5 Laking gives the following description of it:

The hilt might belong to the closing years of the sixteenth century, but the very fine blade associated with it, a blade made by Clemens Horn of Solingen, bears the date 1617. The pommel of the King James I sword is of inverted pear-shape, and is hollow, and constructed of five spiral scrolls a jour. The knuckle guard is flat, swelling in the center where it is pierced with a diamond shaped aperture. The quillons are short and flat, with ribbon pattern ends; from ill treatment they are now possibly more incurved than as originally made. The single bar is constructed on the same principle, and the shell is framed in similar ribbon pattern bands. The decoration of the hilt consists of trophies of arms, festoons and bouquets of flowers and fruit, boldly engraved and gilt upon a russeted groundwork. The whole of this ornamentation is bordered by a beading encrusted in silver. The underside of the bars is entirely gilt and punched with small circles.

The broad blade is elaborately etched and gilt with inscriptions, but unlike some of the other Clemens Horn blades made for England, it bears no device connected with the English royal house. The traditional association with James I must therefore be taken on trust, but the date 1617 on the blade shows that it could have belonged to him. Another sword with pierced pommel is that from the Burrell Collection illustrated in Fig. 2. This hilt is a simpler version of the Windsor sword. It has similar perforations in the hilt and the guards are also of ribbon-like construction, but there are no arms (pas d'dne) to the guard, nor a shell guard. The English association is quite convincing, for it has a Hounslow blade, and it is doubtful whether Hounslow blades ever found a market abroad, where they had to compete with the products of Solingen, Passau and Toledo. It is tempting to attribute a third sword with pierced pommel and guards (Fig. 20) to the same workshop as the other two. The resemblance of this rapier to the two English swords is noticed in the Wallace Collection Catalogue (No. A595), but its attribution there to Germany is based upon the source of the blade. In fact it has not only the same shape of pommel but also the guards are incised with similar motifs, i.e. trophies of arms, festoons, fruit and masks. The technique of applying the decoration is, however, different: whereas the other English swords discussed here have encrusted or damascened ornament, in this case the ornament is chiseled in the metal of the hilt and then overlaid with gold. Similar ornament is found on French hilts and the English origin of this superb rapier must remain less certain. Further evidence for the use of sword-hilts with pierced pommels in England can be found in contemporary portraits. A pommel of this type can be seen on the rapier carried by Francis Manners, 6th Duke of Rutland K.G., in a portrait dated 1614 at Woburn.

Changes After 1625

Fig. 23—Basket-hilted backsword, the hilt encrusted with silver, second quarter of 17th century. (Tøjhusmuseum, Copenhagen)

|

During the second quarter of the 17th century, which is in the reign of Charles I, a number of changes in hilt forms took place. These affected backswords, broadswords and rapiers. A new type of backsword hilt was introduced which was to become the standard horseman's hilt of the Civil Wars. This was a half-basket hilt that offered a great deal of protection to the hand. The example illustrated in Fig. 23, which comes from the Copenhagen Tøjhusmuseum, is typical in form and construction but still shows the silver-encrusted ornament, which by this date was somewhat old-fashioned, chiseled and pierced work being preferred. This hilt was usually roughly chiseled with masks amidst scrolls and the fancied resemblance of these masks to Charles I gave rise in the 19th century to the name Mortuary sword, the idea being that the masks commemorated the Martyr King. In fact the style was introduced long before the execution of Charles I in 1649. It is, however, true that some of the finer hilts of this type were chiseled with bust portraits of Charles I and finished with close-plated silver. The portraits were, of course, patriotic and royalist in intent. These backswords survive in great numbers and of varying quality. The less pretentious examples were finished black or simply painted black with a few of the details of the ornament picked out in gold paint. This was a very perishable type of decoration, but a few examples in good condition have survived. Besides the hilts that appear to show royalist sympathy, others are merely chiseled with figures of warriors, either mounted or on foot or trophies of arms that have no political significance. The finest of all these backswords, now in the C. O. von Kienbusch collection6, is supposed to have belonged to Oliver Cromwell and the blade is inscribed "FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF ENGLAND" with the date 1650, a fact which proves that these hilts were in general use. Of the known Hounslow blades a high proportion are found in this type of hilt, which, when intended for common troopers, was finished with a roughly chiseled feather pattern. Many of these were doubtless made in London, but as the capital was closed to the royalists during the Civil War, the latter must have obtained their supplies elsewhere. Some of the Hounslow blade-makers followed the king to Oxford and it is probable that some of the hilt-makers went with the royalist armies as well. On the other hand, the production of sword hilts does not call for specialist equipment, and it is probable that blacksmiths all over the country turned their hand to making them.

The new type of broadsword is well represented by the two examples in Figs. 24 and 25, each with blade by Johannes Kinndt. One has the earlier ornamentation consisting of silver encrustation, while the latter has the hilt chiseled with masks and scrollwork and finished with silvering. A shell on each side turned upwards towards the pommel and a single knuckle-bow protects the head.

Rapier hilts of the second quarter of the century are usually based on the cup, either pierced in petal-form or in panels running around the cup. The pommel was fluted and of exaggerated elongation (Figs. 26 and 27). An alternative form with flattened pommel and chiseled hilt is shown in Fig. 28. In this case the cup is chiseled with a portrait bust on each side, representing Charles I crowned and his Queen Henrietta Maria. The chiseling is of exceptional quality by English standards of the time but there is no trace of the silvering that was the usual finish of such hilts.

Little is known of the makers of the many superbly decorated hilts of this period. There are a few references to such sword hilts in the records of the London Company of Cutlers. From this source we know that in 1626 the price of a sword with damasked hilt was between forty and fifty shillings. An undecorated hilt was much cheaper. In 1614 the Cutlers' Company supplied 'a very good turky blade and good open hilt' for six shillings.7

Blade Manufacture

Figs. 24 & 25—Two broadswords, the hilt of No. 24 encrusted with silver, that of No. 25 close-plated with silver. Both blades signed by Johannes Kinndt of Hounslow, and dated 1634. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

|

The making and decorating of a sword hilt called for different techniques from the making of blades. Whereas the blade was of steel, the hilt was of softer iron; it was composed of various bars and other members which were hammered to shape by the blacksmith, forged together and then damascened with silver or gold. A noticeable feature of English hilts is the softness of their metal. The quillons have often been bent out of position and the loops fractured. One of the reasons for the softness of the metal used is the fact that the surface had to be sufficiently soft to permit the process of damascening which involved cutting V-shaped channels into which the precious metal could be hammered. If the iron were too hard the sword-furbisher would have difficulty in cutting his grooves and, when the silver or gold was hammered on, the iron would not give way and gain a purchase on the softer precious metal. For the same reason the silver that was used to decorate Elizabethan and Jacobean hilts had to be soft and hence very pure. This meant, however, that the silver decoration did not stand up to wear and it is rare to find such silver-encrusted hilts preserved in pristine condition. The same cutlers who made table cutlery supplied swords and daggers. While no English sword blades, other than the later Hounslow blades discussed below, are known, English table knives were struck with the maker's marks, most of which are recorded in the mark book of the London Cutlers' Company. Moreover, under the Ordinance that followed the grant of James I's Charter to the Company in 1606, the use of the dagger mark was also made compulsory, not only for members of the Company but also for foreigners working in London. These were not literally foreigners but cutlers who were not freemen of the City of London. This regulation is recorded in the Cutlers' Company records of June 25, 1606, when at a Court of the Company were "summoned most parte of the forreyne workinge cutlers in and about the Citie and suburbs of London... and they were generallie charged... to strick a proper marke by the allowance of this howse whereon is on a part thereof to be strock the dagger being the Armes of the Citie." Most of the surviving knife blades of the first half of the 17th century do, in fact, bear the dagger mark together with the personal mark of the cutler and can therefore be readily identified. There was much less space available on a knife handle than on a sword hilt or a dagger handle for damascened decoration, but the shoulders of good-quality London-made knives were decorated in the same way as sword or dagger hilts, with gold damascening or silver encrustation, or with a combination of these two techniques. There can be little doubt that the decoration was carried out by the same craftsmen.

According to Stow's Survey of London, the most influential cutler during the reign of Queen Elizabeth was Richard Mathew, who worked at Fleetbridge. The same source informs us that he was granted a privilege by the Queen for manufacturing knives by a special process, but this was subsequently withdrawn after the other members of the craft had made protests. Presumably he was also a maker of sword hilts, but unfortunately neither knives nor swords by him have hitherto been recognized.

Spurious Foreign Marks

Fig. 26—Rapier with cup hilt composed of radiating petals; mid 17th century. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

|

A good deal more is known about the manufacture of blades than of sword hilts in England. As long as blades were imported from the Continent—that is until the 1630s—the only names that were recognized as a warranty of quality were Spanish, Italian or German: Clemens Horn, Andrea Ferara, Picinino, Juan Martinez and so on. It was not until the foundation of the Hounslow sword factory in 1629 that the Solingen smiths who worked there introduced the practice of signing blades with their own name. The English bladesmiths, so far from putting their own names or marks on their productions, evidently followed the custom of their Solingen contemporaries and struck whatever mark or name seemed to offer the greatest inducement to the potential purchaser. Benjamin Stone, a London entrepreneur who had set up a blademaking factory at Hounslow, wrote in or after the year 1638 to the Office of Ordnance requesting that he be granted the power to hinder the striking of Spanish and other marks upon blades made by the workmen of the London cutlers.8 It follows that some of the blades with transparently false Spanish or Italian marks may be English, and not, as is commonly assumed, of Solingen make. The earliest reference to the manufacture of sword-blades in the records of the Cutlers' Company dates from July 1608 when it was agreed "that suit be made to the Lord Mayor and Council for the provision of such swords and other things appertaining to the Company for the service of the Realm as from time to time hereafter shall be provided for." This does not, however, mean that the manufacture of blades should be undertaken. We have fairly decisive evidence that their production had not begun in 1621. One of the beneficiaries under James I's scheme of granting patents and monopolies to certain favorite courtiers was Thomas Murrey, described as "Secretary to the Princes Highness." He received a patent for the sole making of sword and rapier blades. In July 1621 he made the Company the first offer of this patent, but then latter rejected it "by reason of the large expenses... wch this worck as they thinck will require before it come to perfection... and many other difficulties depending there-upon." It is unlikely that the offer of this monopoly would have been turned down so definitely if the manufacture of sword blades were already a practical possibility. In 1624 the London Cutlers' Company undertook to provide monthly for His Majesty's service 5000 swords with hangers and girdles, the service for which they were required being "when the Earle of Southampton and other honorable persons... employed beyond the seas." It is quite clear that in this case the blades were imported, for arrangements were made by the Company to advance money for the purchase of foreign blades which were sold to the members at a fixed price some eight months later. The first purchase was of 48 dozen blades on April 29, 1624. These were then sold to sixteen members of the Company in parcels of two-dozen costing £5. Other purchases followed during the next three years, the blades being obtained wholesale from merchants in London and Birmingham. Having been made up into swords by the cutlers, they were delivered to the Tower of London where the accounts were finally settled.

Robert South

Fig. 27—Cup-hilted rapier, the blade signed "CASPER CARNIS ME FECIT LONDON," mid-17th century.

(London Museum)

|

The leading London cutler during the first half of the seventeenth century was Robert South, who was appointed Cutler to James I and subsequently held the same office under Charles I. His name first appears in the records of the Cutlers' Company in 1603, when he was described as a member of the Yeomanry of the Company, i.e. he was free but not yet clothed with the Livery. He was Renter Warden in 1628 and Master in 1629. He supplied James I with a number of fine swords and knives and when, three years after the latter's death, he at last obtained payment for "wares delivered to the Office of the Robes in the time of the late King," the amount involved was the considerable sum of £158-15. The only hilt so far attributed to Robert South is that of the sword of Henry, Prince of Wales, illustrated in Fig. 7. This follows the usual fashion of the early decades of the 17th century but is of distinctly higher quality. Another hilt that can be attributed to South is the sword of James I with blade by Clemens Horn in the Windsor Castle armoury. It is not unlikely that South was the importer of the Horn blades and that all the hilts originally furnished with such blades can be attributed to him. Not much is known about him. His name appears again in the records in 1631. On April 22, 1631 his name, together with that of William Cave, is on a petition from the Cutler's Company, addressed to the committee for the Company of Armourers and Gun-makers, which was set up to consider the rates due to these craftsmen and also to establish a list of persons entitled to make or repair arms for the public service. The petitioners requested that they might be joined in the Commission for the supply of swords. Though the request was granted, no action seems to have been taken upon it. Robert South may well have been a promoter of the mill referred to in a Cutlers' Company Minute of June 13, 1631: "At this Court order was given to the Mr. John Porter that he with Mr. Thos. Chesshier and others shold see and vewe a cer-tyne Mill erected for the making of swords blades and to give their judgements and opinions therein at the next Court."9 In the following years South again appears in the Company records, when he had £100 "lent to him for one whole yeare gratis out of the stock of this Howse towards the makeing of Sword and Rapier blades for the good of this Companie and Kingdom." On August 7, 1632, he was granted by the Company the mark of "a Murrian Head to be strouck upon sword blades." He evidently succeeded in setting up his blade factory, for a petition addressed by him in 1639 to the Council of War states that he had supplied 4000 swords for the service of His Majesty's late Northern Expedition to the Office of Ordnance. He goes on to offer the same or a greater number.

The Hounslow Factory

It is now necessary to go back a few years to follow the history of the Hounslow factory, from which so many signed blades survive. The date of its establishment is clearly given by the terms of a petition addressed to King Charles II in 1672. The petitioners, two German smiths named Henry Hoppie and Peter English, stated that they were brought over from Germany (actually Solingen) by Sir William Heydon and King Charles I in 1629. The next date in the history of the factory is July 1, 1636, when a petition to the King was made by Benjamin Stone, blademaker on Hounslow Heath. In this, the first of a series of similar petitions, he stated that he had been at great charge in perfecting the manufacture of sword blades and entreated the King to take into his store 2000 blades which were then in readiness. He further asked that the Lord Treasurer be instructed to advance money for these blades and thereby to encourage the said manufacture, which had never been brought to such perfection before. The petition concluded with the dramatic statement that, as a result of the great expenses he had incurred in the manufacture, he was indebted to various persons in London and dared not walk about as they threatened to arrest him. A note on this petition by the Attorney-General explains that Stone was making sword, rapier, skein (dagger) and other blades for his Majesty's store and for the service of his subjects, which had up to that time been made in foreign parts. This petition was followed by another of the same year. In this, Stone, who must have been a man of means, stated that at his charge, namely £6000, he had perfected the art of blade-making, so that he made "as good as any that are made in the Christian world." As a result of great complaints made by the Lord Deputy of Ireland and others of the unserviceableness of the swords brought into the Office of the Ordnance by the cutlers, his Majesty had ordered that the Office of the Ordnance should be supplied with blades made by the petitioner, who was thereupon made a member of the Office and undertook to make 500 blades a week. He went on to complain that the London Cutlers' Company had received orders to supply 4000 swords "which were for the most part old and decayed" although he had great quantities lying on his hands and was ready to deliver hi short tune any proportion his Majesty should have occasion to use. The petition concluded with the request that no further blades should be admitted to the Office of Ordnance that had been made abroad. This attack on the Cutlers was rejected by the Company; in their reply they alleged, "that the swords which he petitioneth to be received into the store and pretends to be blades of his own making, are all bromedgham (i.e. Birmingham) blades, they are no way serviceable or fit for his Majesty's store."

This last claim is of particular interest as it shows that the manufacture of sword blades in Birmingham had already started and that the London trade did not place much store upon them, though this may have been due to commercial rivalry. In a final petition, also dated 1638, Stone describes himself as Cutler for the Office of the Ordnance' and states that he has spent £8000 (all his estate) in the manufacture of blades and is able to deliver 1000 per month.

German Workmen

Fig. 28—Cup-hilted rapier, the cup pierced and chiselled with portrait heads of Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria; second quarter of 17th century.

(Private Collection)

|

Whether Benjamin Stone was in control of all the German immigrant bladesmiths then working at Hounslow is not clear. In view of the quantity of blades he was able to supply, this seems likely. Production had certainly begun long before Stone's petitions, for signed blades of earlier date are known. Thus Johannes Kinndt, who sometimes anglicised his name as John Kennet, is represented by five blades bearing his signature together with the location Hounslow and the dates 1634 or 1635. Three are in the London Museum,10 the other two are in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Johannes Hoppie, perhaps the father of the Henry Hoppie who signed the 1672 petition, is also represented by signed blades dating from before 1636. It seems that Hoppie did not go directly to Hounslow when he came from Solingen, but was first established at what would seem to be the obvious place for a German, namely Greenwich, where Henry VIII's Almain armourers had been settled and where the royal armouries still existed. His presence there is proved by the existence of a sword with blade signed "IOHANNES HOPPE 1634 ME FECIT GRENEWICH IN ANGLIA." The postscript "IN ANGLIA" can be explained by the fact that Hoppe wished to establish that he was now working in England. A daughter of John Hoppie was christened at Greenwich Parish Church in 1632, so we can reckon with a sojourn there of some years. In addition to the blade signed Greenwich there are others by John Hoppie signed London; these also probably date from his Greenwich period. It is possible that the Solingen bladesmiths working at Hounslow may have begun by signing their wares LONDON, but this seems unlikely. Although Hounslow is now a suburb of London, it is some twelve miles distant from the city and could in the 17th century hardly be regarded as belonging to the purlieus of London. Another German smith who signed LONDON was Kaspar Fleisch. The blade of the sword illustrated in Fig. 27 is signed "CASPER CARNIS ME FECIT LONDON"; Carnis is, of course, the Latinised version of the German word Fleisch.

Fig. 29—Underside of cup-hilt, shown in Fig. 28.

|

Judging by the number of extant signed blades, one of the most important of the German smiths at Hounslow was Peter Munsten, who came from a well-known Solingen family. His name does not, however, appear in the various documentary references to the Hounslow factory and it has been suggested that he may have changed his name to Peter English. He may have chosen another name because Munsten does not readily lend itself to Anglicization. The last of the German smiths who is believed to have worked at Hounslow is Clamas Meigen, whose name appears on a number of rather rough broadsword blades.

Besides the Germans, a number of English-born smiths worked at Hounslow, and blades signed by them survive. These include Richard Hopkins, represented by a sword in the London Museum11 with blade signed "RECARDUS HOPKINS FECIT HOUN-SLOE," and Joseph Jencks, represented by a sword in an English private collection signed "JOSEPH JENCKES ME FECIT HOUNSLO." Jencks is the only working Hounslow smith who is known to have been a member of the London Cutlers' Company. His mark, a thistle with a dagger, is found on a number of finely finished table-knives. The majority of the Hounslow blades are not signed with the smith's name, and it is probable that the practice was given up. It seems that the earlier blades are signed while the later ones, which are often more roughly finished, bear only the name "HOUNSLOE" or "ME FECIT HOUNSLO."

Slow Decline and Cessation

The Hounslow factory is shown on the map published by Moses Glover in 1635, as is "Mr. Stones' house."12 Stone's name does not appear on any of the blades, although he was a member of the Cutlers' Company and actually had a mark allotted to him. It is clear from the statements in his petitions that he became a merchant and was more concerned with the financing and organization of blade manufacture in England. As Hounslow was outside the jurisdiction of the London Company, the German smiths did not need to secure admission to the Company, which would in any case probably have been refused. During their early days in England, when they seem to have worked in London, they probably enjoyed royal protection against interference by the Company. When the Civil Wars began, the Hounslow bladesmiths seem to have split into two camps according to their political sympathies. We know from the 1672 petition that Hoppie and English followed Charles I to Oxford and that Cromwell confiscated their mills and turned them into powder mills.13 On the other hand Johann Kinndt (Kennet) remained at Hounslow; a letter from Sir William Waller, dated April 1643, to Parliament requests the supply of "200 Horsemen's swords of Ken-net's making of Hounslow." The bladesmiths who remained at Hounslow were not without their difficulties for in 1649 their tools and stock in trade were distrained upon by the Commissioners of Taxes for non-payment of taxes due. The bladesmiths petitioned the Council of State with satisfactory results, for the latter sent a stiff minute to the Tax authorities requiring them to return the tools, which should not have been distrained upon as long as any other appropriate surety could be found. Further, the Commissioners were instructed to examine the bladesmiths' petition and to "take order that in future assessments they may not be oppressed with payments beyond their proportions, and that their working tools be made good to them and the manufacture may have all encouragement."

The latest dated Hounslow Blade is of the year 1637 but there are many references to the blade factory of later date. In 1650 an order was made to deliver ten trees from Windsor Forest to Paul and Everard Ernious, "strangers," for the repair of the sword mills. Various petitions dating from between 1650 and 1660 from John Cook, Gentleman, refer to "the encouragement of his manufactory of sword and rapier blades at Hounslo," In spite of the critical comments of the London Cutlers' Company, the Hounslow blades were quite serviceable; according to the account of Benjamin Stone in the Dictionary of National Biography, some of his blades were shown to Robert South, the royal cutler, described as of Toledo make and accepted by him as such. William Cavendish, first Duke of Newcastle (1592-1676), refers to the high quality of Hounslow blades in two of his plays.

About the Author

Mr. Hayward, an art historian of international repute, has greatly advanced the serious study of arms and armor throughout his many years with the Victoria & Albert Museum and as an Associate Director of Sotheby & Co. His articles and monographs are by far too numerous to list; they have been published in most major languages in the world.

Notes

1. Ill. H.A. Schmidt, Hans Holbein de Jüngere, Basel, 1945, fig. 139.

2. Christian IV of Denmark (1588-1648) was appointed Knight of the Garter in 1605 and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden in 1628.

3. F. Grose, Treatise on Antient Armour, Vol. II, pi. 33.

4. See E.A. Christensens Vaabensamling, Vaabenhis-toriske Aarbtfger, Copenhagen, 1935, pi. C5.

5. Ill. Laking, The Armoury of Windsor Castle, pi. 9, cat. no. 62.

6. Ill. Kretschmar von Kienbusch Collection, Princeton, 1963, pi. CIV, cat. no. 356.

7. This and the following extracts from the records of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers of London are taken from Charles Welch, History of the Cutlers' Company, London, 1922.

8. This and the following extracts concerning the petitions addressed by Benjamin Stone to the Office of Ordnance are taken from the Calendars of State Papers for the appropriate years. For further information concerning Benjamin Stone see Meredith Colket, "The Jenks Family of England," The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, Vol. CX, nos. 437-440, 1956.

9. Thomas Cheshire was probably an associate of Robert South; his name appears as well as that of South as a supplier of richly decorated swords to the Royal Wardrobe.

10. Ill. M.R. Holmes, Arms and Armour in Tudor and Stuart London, London, 1957, pis. xii and xiii.

11. Ill. ibid. pl. xviii.

12. Ill. M. Colket, op. cit. pls. 3 and 6.

13. S.P. Dom. Car. II, 295.41.

|

|