Hi,

Long time lurker, first time poster - be gentle ;)

Reiner's post about sickle fighting (http://www.myArmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.php?t=17177) got me thinking about a peasant (or other civilian) and his relationship to his weapons. I'm primarily thinking about during the various peasant rebellions that cropped up across Europe - peasants becoming outraged at something, militarising their usual tools and marching into battle. Let's imagine our peasant has grabbed his sickle, scythe, flail or whatever and then gone into battle. Let's assume he survived. My question is whether or not he would then loot the battlefield and replace his improvised weapons with "proper" ones. Would he put down his sickle and pick up a sword? Fundamentally, would he put down a tool he's very familiar with, one possibly used every day for most of his life, to pick up something unfamiliar but better suited to the task at hand. Daggers, knives etc - I'm sure our erstwhile antagonist would pocket them. If he had just had a long stick (and somehow managed to survive the initial battle) I imagine using a spear wouldn't be too much of a stretch. If he had a militarised scythe? I guess a glaive or similar cutting polearm would also be close enough to what he was used to (but would the weight of the blade / balance make this troublesome?). But what about if he had a sickle or big agricultural flail - they don't seem particularly analagous to any other "standard" weapons in terms of style and usage. Wouldn't he be better, more effective, sticking with what he knows rather than picking up something weighted and balanced very differently and used in a completely different way?

All opinions gratefully received.

D

Question is, has he ever before used his scythe or whatever in a fight, or to kill?

If you have to learn the 'noble' art of killing people in battle, I don't think it will matter much what kind of weapon you are using.

Although he may be very comfortable cutting plant material with his scythe, he has got no battle experience with it.

So, if he could upgrade to a tool more designed for that job, why wouldn't he? I would....... :D

If you have to learn the 'noble' art of killing people in battle, I don't think it will matter much what kind of weapon you are using.

Although he may be very comfortable cutting plant material with his scythe, he has got no battle experience with it.

So, if he could upgrade to a tool more designed for that job, why wouldn't he? I would....... :D

| A Visser wrote: |

| Question is, has he ever before used his scythe or whatever in a fight, or to kill?

If you have to learn the 'noble' art of killing people in battle, I don't think it will matter much what kind of weapon you are using. Although he may be very comfortable cutting plant material with his scythe, he has got no battle experience with it. So, if he could upgrade to a tool more designed for that job, why wouldn't he? I would....... :D |

I'd imagine not - no. But I would have thought the mere fact that he's comfortable with the weight, the balance and how the tool / weapon fundamentally works (swing side to side or whatever) would mean that deciding to put that scythe down and picking up, for example, a sword - something used in a completely different way - would at least take some serious soul-searching.

Dedicated weapons are as a rule always better, and usually simpler to use as well.

While you CAN fight with almost any item that is handy, and even win under the right circumstances, spears, axes and swords where the most common figting tools throughout human (pre firearm) history for a reason.

Most importantly, spears and swords are relatively easy to use. they are faster and more handy than agricultural tools, and generally have more reach as well.

Scytes and flails are slow, clumsy weapons that must be used in a spesific way to be dangerous. The fast stab of the spear will most likey stopp a swung flail under most cicumstances.

The most sucsessfull "peasant" weapons, like the Godendag or bill, are both weapons with a decent stabbing potential, solid block, and heavy puch against outnumbered opponents. The flail or scyte, on the other hand, have a weaker block, no tabbing potential, and must be swung in a large motion to be effective.

Militariced schytes where usually bent upwards, to form a simple form of Glaive.

While you CAN fight with almost any item that is handy, and even win under the right circumstances, spears, axes and swords where the most common figting tools throughout human (pre firearm) history for a reason.

Most importantly, spears and swords are relatively easy to use. they are faster and more handy than agricultural tools, and generally have more reach as well.

Scytes and flails are slow, clumsy weapons that must be used in a spesific way to be dangerous. The fast stab of the spear will most likey stopp a swung flail under most cicumstances.

The most sucsessfull "peasant" weapons, like the Godendag or bill, are both weapons with a decent stabbing potential, solid block, and heavy puch against outnumbered opponents. The flail or scyte, on the other hand, have a weaker block, no tabbing potential, and must be swung in a large motion to be effective.

Militariced schytes where usually bent upwards, to form a simple form of Glaive.

Although one can kill a man with a flail, one can't thresh grain with a sword. The peasant still has to work, assuming he isn't caught and blinded or otherwise crippled. He needs the flail more than he needs the sword, and since he is probably as efficient with the former as a professional soldier would be with the latter, I'd put my money on the polearm in a match between the two.

Keep in mind that the common feature of most european peasant rebellions where that they where drowned in seas of blood, and that high and late middle age warfare was characterised by near total exclusion of light melee infantry from the battlefield, until the appearance of highly trained mercenary pikemen.

This does not indicate that a lone peasant with an improviced weapon would stand much of a chance against a lone professional soldier on open ground.

This does not indicate that a lone peasant with an improviced weapon would stand much of a chance against a lone professional soldier on open ground.

| Elling Polden wrote: |

| Keep in mind that the common feature of most european peasant rebellions where that they where drowned in seas of blood, and that high and late middle age warfare was characterised by near total exclusion of light melee infantry from the battlefield, until the appearance of highly trained mercenary pikemen.

This does not indicate that a lone peasant with an improviced weapon would stand much of a chance against a lone professional soldier on open ground. |

The level of training as well as the weapon advantage of the soldier over the peasant who may never have killed anyone or fought a serious deadly encounter: The ruthlessness of a professional soldier, mercenary or outlaw used to blood and guts and having no compunctions about killing: A battle hardened wolf against a timid sheep dog or even worse the sheep themselves !

Now, some peasants might in some cases depending on time and place be an ex-soldier or part of a local militia and have some real fighting experience i.e. that farmer with the sickle might be a hardened veteran of a previous war. ;)

If there was time to prepare the " peasant " might be digging up some real weapons and or armour hidden in the attic or buried in the barn assuming that peasants were not supposed to be armed in some societies ! In other societies ( Britain ) he might just go get his longbow and make any soldier(s) or bandit(s) miserable. ;) :p :lol:

All this said, what Elling said about most peasant revolt turning out badly for the peasants makes sense as " professional soldiers " would almost always have the advantage.

First off, I think we need to examine the term "peasant." Peasants were the workers of the common social class. During the Middle Ages, society in Europe was very complex. The modern idea of upper class, middle class, and lower class did not exist like they do today. Things were more fluid and yet at the same time more rigid.

Typically, medieval society could be divided several different ways. There were birth divisions and professional divisions, amongst others. Divisions by birth were simple: you were either common born or gentle born. This was a perceptive division. Commoners were not perceived to be able to appreciate the finer or gentler things in life, whereas the gentle born were considered so able. This had nothing to do with wealth or profession. You could have gentle born servants and wealthy common merchants. The boundary between common and gentle can still be evidenced today by example of nouveau rich versus old money wealth. You can win the $232 million Powerball jackpot, but not be accepted in the Hamptons.

Professional divisions divided people by what they did: military, clergy, and peasantry. The man-at-arms fought for all, the churchman prayed for all, and the peasant worked for all. Just as not all men-at-arms were knights, not all peasants were laborers. Agreements existed between the social classes in the feudal system. In return for the protection of the local manorial lord (be he a knight or a duke) the local peasantry would grow food to support the lord. The clergy, in return for food and protection, entreated God on behalf of the lord and the peasants to save their souls.

Peasants could be roughly divided into three groups: laborers, husbandmen, and yeomen. Laborers are the stereotypical peasant, or at least as it is thought of in the modern mind. They could not afford to own their own land and paid rent to the local landowner by working that land for the landowner. Their belongings were typically of a courser and poorer quality. Husbandmen were the "middle class" of the peasantry. They owned their own land, which was just large enough to support their family, and could afford to hire laborers. They owed fealty to the local manorial lord but were not indentured to the land. They often gave military service to their lord, received a minimum of military training, and owned at least a helmet and bow and maybe a sword. The yeoman was the upper end of the scale. Yeomen owned enough land to support themselves, hire husbandmen and laborers, and rent land out to others. While many provided military service as archers, the wealthier yeoman might serve as a man-at-arms.

The original poster seems to infer that a peasant wouldn't know much about how to use a sword, but that was not always the case. Yes, certain training was proscribed to the common person, such as the longsword or the pole axe, because they were considered gentlemen's weapons, but the commoner had access to many other weapons such as the single handed sword, the axe, and the bow.

Typically, medieval society could be divided several different ways. There were birth divisions and professional divisions, amongst others. Divisions by birth were simple: you were either common born or gentle born. This was a perceptive division. Commoners were not perceived to be able to appreciate the finer or gentler things in life, whereas the gentle born were considered so able. This had nothing to do with wealth or profession. You could have gentle born servants and wealthy common merchants. The boundary between common and gentle can still be evidenced today by example of nouveau rich versus old money wealth. You can win the $232 million Powerball jackpot, but not be accepted in the Hamptons.

Professional divisions divided people by what they did: military, clergy, and peasantry. The man-at-arms fought for all, the churchman prayed for all, and the peasant worked for all. Just as not all men-at-arms were knights, not all peasants were laborers. Agreements existed between the social classes in the feudal system. In return for the protection of the local manorial lord (be he a knight or a duke) the local peasantry would grow food to support the lord. The clergy, in return for food and protection, entreated God on behalf of the lord and the peasants to save their souls.

Peasants could be roughly divided into three groups: laborers, husbandmen, and yeomen. Laborers are the stereotypical peasant, or at least as it is thought of in the modern mind. They could not afford to own their own land and paid rent to the local landowner by working that land for the landowner. Their belongings were typically of a courser and poorer quality. Husbandmen were the "middle class" of the peasantry. They owned their own land, which was just large enough to support their family, and could afford to hire laborers. They owed fealty to the local manorial lord but were not indentured to the land. They often gave military service to their lord, received a minimum of military training, and owned at least a helmet and bow and maybe a sword. The yeoman was the upper end of the scale. Yeomen owned enough land to support themselves, hire husbandmen and laborers, and rent land out to others. While many provided military service as archers, the wealthier yeoman might serve as a man-at-arms.

The original poster seems to infer that a peasant wouldn't know much about how to use a sword, but that was not always the case. Yes, certain training was proscribed to the common person, such as the longsword or the pole axe, because they were considered gentlemen's weapons, but the commoner had access to many other weapons such as the single handed sword, the axe, and the bow.

| Jonathan Blair wrote: |

| Yes, certain training was proscribed to the common person, such as the longsword or the pole axe, because they were considered gentlemen's weapons, but the commoner had access to many other weapons such as the single handed sword, the axe, and the bow. |

Also, the ubiquitous messer and hunting spear.

| Sean Flynt wrote: | ||

Also, the ubiquitous messer and hunting spear. |

True. I'd surmise that the biggest difference between the "professional" and the peasant, first of all, was logistical infrastructure and logistical support. Tactical considerations can make a difference, but not as much of a difference as we moderns who are fascinated with them tend to make out.

Though dedicated warriors were well-equipped, that included having a social support system to try to make sure they had adequate food, water, clothing, shelter etc., so that by not concerning themselves with these matters they could concern themselves with war. Far more battles thoughout history, and especially campaigns, have been lost because of logistical considerations than because of tactical specifics.

Where would a peasant army's logistical support be? They were used to providing staples like food, but did not control the storage, safe-keeping or transport. A peasant army taking to the march risked far more than one dedicated to battle. Especially when it comes to entire campaigns; there is no shortage of instances of individual battles where a fierce "rabble" army was underestimated by seasoned soldiers only to annihilate the professionals--but then the upstarts fell apart under the vicissitudes of sustaining a campaign.

Then too, at the high end of logistics, the peasants would lack a preexisting, solid, mutually accepted command structure (not to mention reconnaisance capability, etc.) They wouldn't be used to being formed up as units and following that command structure.

None of which has much to do with individual toughness, or even skill with a weapon.

All in all, I'd hypothesize than an individual peasant of tough disposition, if pushed so far he wanted to fight, would prove a significant threat to an individual soldier. Odds would still favor the trained warrior, but though one-on-one martial skill can be a noticeable advantage, it's never been close to creating a certain outcome. Especially if the encounter is not a "duel" under accepted, "equal" conditions, which seems it'd be rare between the professional and the peasant anyway.

I'd argue it's on the level of units and their logistical support where we might instead explain how doomed most peasant rebellions were.

Many places in various times had militia laws, so a lot of those "peasants" already had weapons and at least basic training. I have a feeling such men would have formed the core of any revolt. Hunting spears and bows were probably not very common in a largely agrarian area, but there could be some.

Being extremely experienced with the use of a grain flail does not make one a good fighter with it. Thumping defenseless grain on the ground and facing a trained armored killer are rather different things! But yes, if he survives the day, ANY poorly-armed peasant is going to scrounge a decent weapon that he comes across. (And that doesn't mean he's going to chuck his farm tool!) Mind you, there won't be enough to go around--any victorious peasant force will outnumber its opponents by quite a bit, and not all of the enemy will die or leave their weapons behind.

Make spears. Cheap and simple, easy to use, and you're going to need a lot of them.

Matthew

Being extremely experienced with the use of a grain flail does not make one a good fighter with it. Thumping defenseless grain on the ground and facing a trained armored killer are rather different things! But yes, if he survives the day, ANY poorly-armed peasant is going to scrounge a decent weapon that he comes across. (And that doesn't mean he's going to chuck his farm tool!) Mind you, there won't be enough to go around--any victorious peasant force will outnumber its opponents by quite a bit, and not all of the enemy will die or leave their weapons behind.

Make spears. Cheap and simple, easy to use, and you're going to need a lot of them.

Matthew

| Robert Subiaga Jr. wrote: |

|

True. I'd surmise that the biggest difference between the "professional" and the peasant, first of all, was logistical infrastructure and logistical support. Tactical considerations can make a difference, but not as much of a difference as we moderns who are fascinated with them tend to make out. Though dedicated warriors were well-equipped, that included having a social support system to try to make sure they had adequate food, water, clothing, shelter etc., so that by not concerning themselves with these matters they could concern themselves with war. Far more battles thoughout history, and especially campaigns, have been lost because of logistical considerations than because of tactical specifics. Where would a peasant army's logistical support be? They were used to providing staples like food, but did not control the storage, safe-keeping or transport. A peasant army taking to the march risked far more than one dedicated to battle. Especially when it comes to entire campaigns; there is no shortage of instances of individual battles where a fierce "rabble" army was underestimated by seasoned soldiers only to annihilate the professionals--but then the upstarts fell apart under the vicissitudes of sustaining a campaign. Then too, at the high end of logistics, the peasants would lack a preexisting, solid, mutually accepted command structure (not to mention reconnaisance capability, etc.) They wouldn't be used to being formed up as units and following that command structure. None of which has much to do with individual toughness, or even skill with a weapon. All in all, I'd hypothesize than an individual peasant of tough disposition, if pushed so far he wanted to fight, would prove a significant threat to an individual soldier. Odds would still favor the trained warrior, but though one-on-one martial skill can be a noticeable advantage, it's never been close to creating a certain outcome. Especially if the encounter is not a "duel" under accepted, "equal" conditions, which seems it'd be rare between the professional and the peasant anyway. I'd argue it's on the level of units and their logistical support where we might instead explain how doomed most peasant rebellions were. |

On the other hand the local peasants might gain an advantage by fighting on their own ground, in an environment familiar to them. This goes both for tactical and logistical aspects, and is true for many of the campaigns in late medieval and early modern Sweden where armies were largely composed of local peasant militias. These regularly proved to be more than able to stand their ground against Danish/Union armies made up by men-at-arms and professional mercenaries, provided that the terrain and local conditions favoured the former. An interesting parallel to this is also the repeated Danish failures at the hands of the armies of the peasant republic of Dithmarschen.

Some medieval towns trained standing militias for emergency defence. This tended to be the norm throughout a substantial portion of Italy and Spain. Belgium in the battle of the golden spurs may be one other good example. Town revolts against monarchy or feudal rule were also pervasive near the end of the 100 year war, and, town militias seemed to give the governing military plenty of trouble with whatever tactics and weapons they did have. The stave or staff was actually a pretty common item. Limited approach through swampy terrain, rows of sharpened stakes, and guild members + youth with staves defeated much of the elite French heavy cavalry according to some accounts of the battle of the golden spurs.

I like the clever play of words on Oakeshott's 'A Knight and His Weapons'.

It's had to tell what farm tools were able to be converted to effective fighting weapons. Was a pitchfork any good? How will we ever know?

There were a few tools that made the jump to warfare easily. The Flail in particular was very effective. Think of all the surviving variations of the two handed war flail in different musuems and collections. Why construct so many of these things unless the original model they were based on (threshing flail) was proven to be formidable in battle? We also know that English infantry prefered the hewing power of a Billhook on a pole over the defensive thrusting power of pikes and spears. And shouldn't the axe be considered a 'peasant' weapon as well?

There were a few tools that made the jump to warfare easily. The Flail in particular was very effective. Think of all the surviving variations of the two handed war flail in different musuems and collections. Why construct so many of these things unless the original model they were based on (threshing flail) was proven to be formidable in battle? We also know that English infantry prefered the hewing power of a Billhook on a pole over the defensive thrusting power of pikes and spears. And shouldn't the axe be considered a 'peasant' weapon as well?

We did a few sperimentation with some of the peasant's weapons, like the grain's flail, and I'm convinced that they can be fearsome weapons, but overall under the standards of true weapons.

The grain's flail (which in Como we call "Fiel") is truly devastantig, for one blow. Reload for a second hit is a long operation, for the distribuition of the mass and the system of linking (I copied the one on an original fiel, only doing it with a metal chain, not leather, like you can see in the bible).

Other are more useable, like the hay-cutter or the fauchard, but you can fell the need of a straight point to finish an armored opponent (with a hit under the chin... ). If I were a peasant I would use one of my instruments only until I can find one true weapon, or modify the to a more suitable form (I remember an illustration of a blacksmith modifing scythes in glaives during a farmer's rebellion).

The grain's flail (which in Como we call "Fiel") is truly devastantig, for one blow. Reload for a second hit is a long operation, for the distribuition of the mass and the system of linking (I copied the one on an original fiel, only doing it with a metal chain, not leather, like you can see in the bible).

Other are more useable, like the hay-cutter or the fauchard, but you can fell the need of a straight point to finish an armored opponent (with a hit under the chin... ). If I were a peasant I would use one of my instruments only until I can find one true weapon, or modify the to a more suitable form (I remember an illustration of a blacksmith modifing scythes in glaives during a farmer's rebellion).

Countries and regions that lacked a large warrior aristocracy maintained leavied infantry throughout the middle ages. In Scandinavia, or in the individual italian city states, there are simply not enough potential Knights to form a army.

In France, for instance, you could raise an army of 10000, consisting purely of heavy cavalry.

A typical example is Scottland during the revolts of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.

In the high middle ages, Scotland was organiced along the same feudal lines as England. Cavalry was the priviledged fighting arm, leading to a lesser focus on training and equiping the infantry. (Norwegian descriptions of the scottish forces at Largs(1263) say that the cavalry was very impressive, but that the infantry was rabble)

However, the english could field several times as many knigths as the scots, so deciding the battle with cavalry power was not an option.

So, what do you do?

Focus on drilling and maximising the effect of your spearman infantry.

The result was very impressive, and foreshadowed the later sucsess of pikemen. Not only did the well drilled infantry defeat the enemy cavalry, but also smashed the less organiced infantry of the cavalry-focused foe.

The English, beeing quick learners, used the same tactics against the French, but utilizing dismounted men at arms, as they actually had suficient number of these, using the milita as non-melee archers.

With the introduction of pike drill, the peasntry gave better "value for money" as pikemen than as archers, resulting in the quite rapid decrease in longbow archers in english armies in the late 1400s.

In France, for instance, you could raise an army of 10000, consisting purely of heavy cavalry.

A typical example is Scottland during the revolts of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.

In the high middle ages, Scotland was organiced along the same feudal lines as England. Cavalry was the priviledged fighting arm, leading to a lesser focus on training and equiping the infantry. (Norwegian descriptions of the scottish forces at Largs(1263) say that the cavalry was very impressive, but that the infantry was rabble)

However, the english could field several times as many knigths as the scots, so deciding the battle with cavalry power was not an option.

So, what do you do?

Focus on drilling and maximising the effect of your spearman infantry.

The result was very impressive, and foreshadowed the later sucsess of pikemen. Not only did the well drilled infantry defeat the enemy cavalry, but also smashed the less organiced infantry of the cavalry-focused foe.

The English, beeing quick learners, used the same tactics against the French, but utilizing dismounted men at arms, as they actually had suficient number of these, using the milita as non-melee archers.

With the introduction of pike drill, the peasntry gave better "value for money" as pikemen than as archers, resulting in the quite rapid decrease in longbow archers in english armies in the late 1400s.

Weren't most peasant rebellions formed around a nucleus of veteran soldiers? The English Peasants Revolt of the 1381, for instance, included quite a few veterans of the French wars, IIRC, and of course all Englishmen practiced at the butts every Sunday.

-Wilhelm

-Wilhelm

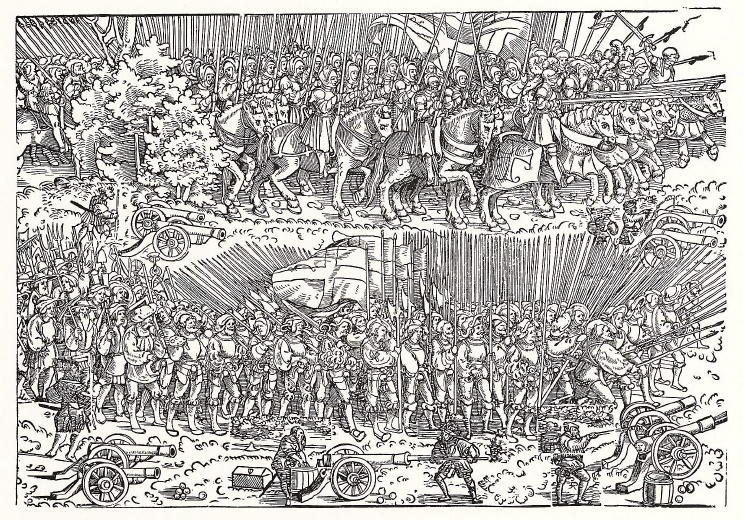

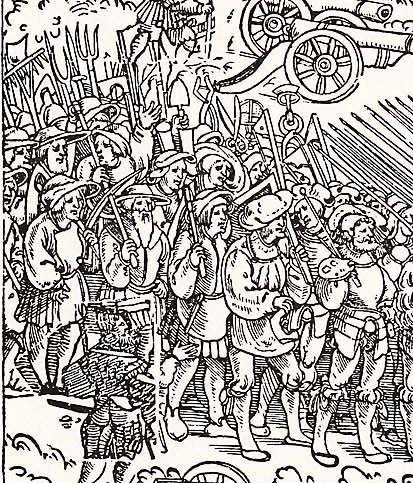

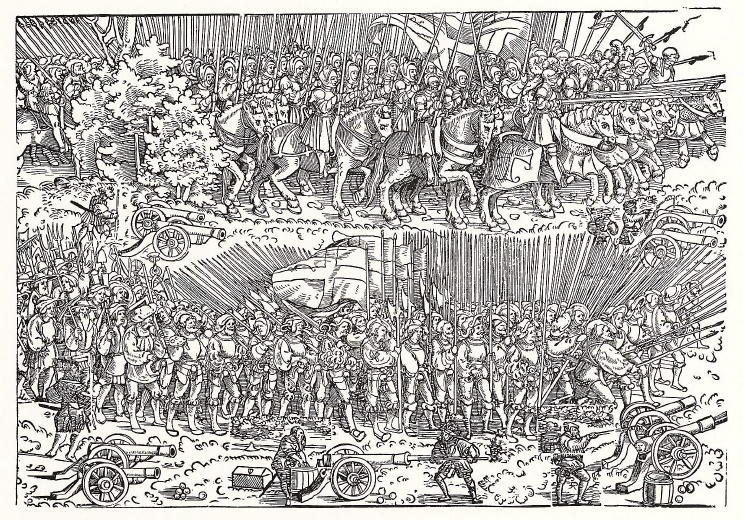

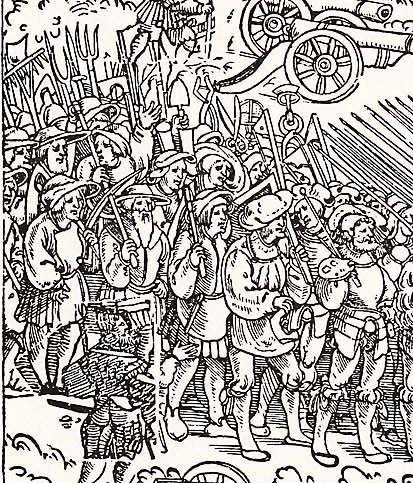

An illustration from 1525 showing landsknecht and "peasants" together in preperation for a battle. In the background and foreground there are the mounted knights and artillery with the peasants taking up a position behind the main body of landsknechts. The artist has portrayed them as possessing a motley collection of farm impliments and tools; there can be seen forks, rakes, picks and shovels along with an axe or two and oddly enough some shears and tongs. There are no spears, swords or halberds. One thing that is clear is that there is no armour amongst the peasants, so a discussion about the arms of the peasant is one thing but even if two equally experienced and equally armed forces were to face one another the one with armour would likely have an advantage.

Also, i'm not sure that I would agree with an earlier post's assessment that peasants at war would be akin to dogs vs wolves or even sheep. It should be remembered that generally the medieval era had much higher rates of violence and murder; look at the italian city communes and the intercine killings and the raiding over the scottish borders. It could be argued that on the whole the "peasant" class may have been much more "up for it" than we give them credit for. They would have been a lot closer to "gritty real life" than soft westerner's; killing their own beasts, working hard in the fields or at a trade, babies, children, friends and family dying of disease, at times, one bad harvest away from famine. I think that on the whole they would have been be a hell of a lot tougher than most of us. The fact that they were frequently decimated in battle should not be used as a commontery upon their fighting spirit or "guts". As has been said, without logistical support, artillery and significant cavalry, coupled with a lack of armour any peasant army would have been vulnerable to a more professionally led and equiped force. What is interesting though is that, given all their disadvantages in equipment, support and leadership, there are many peasant revolts. So, in my opinion, they were "up for it"; they didn't back away from a fight, and sure, they fought and died, but they did take up the few arms they had and take on vastly superior forces; that does not sound like the behaviour of a sheep.

Also, remember that city militias were made up of lower classes and that the soldiery of the professional mercenary armies were likely drawn from the landless and tradesless underclasses who joined up hoping for plunder or at least a wage. The swiss mercenaries were drawn from the lower classes and were some of the most formidible fighters of the late medieval, early renaissance period.

My 2 cents worth (or at the moment, my 1.62 cents worth)

"It's not the size of the dog in the fight, it's the size of the fight in the dog. "

Mark Twain

Attachment: 198.14 KB

Attachment: 198.14 KB

Attachment: 141.79 KB

Attachment: 141.79 KB

Also, i'm not sure that I would agree with an earlier post's assessment that peasants at war would be akin to dogs vs wolves or even sheep. It should be remembered that generally the medieval era had much higher rates of violence and murder; look at the italian city communes and the intercine killings and the raiding over the scottish borders. It could be argued that on the whole the "peasant" class may have been much more "up for it" than we give them credit for. They would have been a lot closer to "gritty real life" than soft westerner's; killing their own beasts, working hard in the fields or at a trade, babies, children, friends and family dying of disease, at times, one bad harvest away from famine. I think that on the whole they would have been be a hell of a lot tougher than most of us. The fact that they were frequently decimated in battle should not be used as a commontery upon their fighting spirit or "guts". As has been said, without logistical support, artillery and significant cavalry, coupled with a lack of armour any peasant army would have been vulnerable to a more professionally led and equiped force. What is interesting though is that, given all their disadvantages in equipment, support and leadership, there are many peasant revolts. So, in my opinion, they were "up for it"; they didn't back away from a fight, and sure, they fought and died, but they did take up the few arms they had and take on vastly superior forces; that does not sound like the behaviour of a sheep.

Also, remember that city militias were made up of lower classes and that the soldiery of the professional mercenary armies were likely drawn from the landless and tradesless underclasses who joined up hoping for plunder or at least a wage. The swiss mercenaries were drawn from the lower classes and were some of the most formidible fighters of the late medieval, early renaissance period.

My 2 cents worth (or at the moment, my 1.62 cents worth)

"It's not the size of the dog in the fight, it's the size of the fight in the dog. "

Mark Twain

Christopher, some might of been 'up for it' but by the looks of their faces in that close up, they sure aren't! :lol:

Page 1 of 3

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum