| Author |

Message |

Alexi Goranov

myArmoury Alumni

|

Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 10:21 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 10:21 am Post subject: |

|

|

Hi Felix,

you are making a good point about armour, and I should have mentioned it when I was listing other factors that affect the outcome of a an individual (one on one or one on few) battle. You make a statement about whish I have wondered a lot. Who used the war swords? If it were only the nobility, then all you say is virtually true.

But do we really know that only the nobility or armoured soldiers dared to use a sword in combat? I am trying to research the issue as I have had this question about prevalence of sword use during battles. I think one has to also be careful about the historic time period we talk about. The prevalence of sword use might be have been different from century to century. I do not know the answers to these questions, so I cannot make any hard conclusions about sword use one way or another.

Matt,

you make the point that the master strikes do not work against shields. I agree. But I doubt that a deliberate strike against a shield for the sole purpose of hitting the shiels is useful, or masterful. As I understand it, if you attack an opponent masterfully at his openings and make him work (i.e. defend with his shield or sword) you will beat him sooner or later. If one is preoccupied with defence, their offence is neglected. It sounds nice and easy on paper but in reality it does not always work so easily. Experience is needed to achieve mastery of any skill.

The opposite is true as well. If the initiative is taken from the long-swordsman and he cannot regain it, he will lose.

(excuse my not so politically correct language, as I have referred to my imaginary combattants as males)

Stamina, attitude, morale, and experience have decided battles more often then sheer numbers and degree of armament.

Along these lines is one of my favorite sayings: "The more committed usually wins"

Then again, I might be wrong....................

Yours,

Alexi

|

|

|

|

|

Don Stanko

|

Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 10:53 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 10:53 am Post subject: |

|

|

Maybe there is entirely too much focus on personal encounters. Afterall, it is called a War Sword, we can all agree on that. The next logical place to search would then be Medieval military tactics. What did the skirmish lines look like? How were the troops gathered? (in tens, hundreds?) and finally try and answer if these were in fact saddle swords, used only on horseback or were they used more on foot? In the book "the sword in the age of chivalry" they make reference to the saddle sword but bring up the point that there is nothing that states how large these swords were. In addition, great swords are depicted as being worn on the belt at times.

Unfortunately, I bring to the table only questions - I have none of the answers.

Don

|

|

|

|

Alexi Goranov

myArmoury Alumni

|

Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 11:54 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 11:54 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Don Stanko wrote: | Maybe there is entirely too much focus on personal encounters. Afterall, it is called a War Sword, we can all agree on that. The next logical place to search would then be Medieval military tactics. What did the skirmish lines look like? How were the troops gathered? (in tens, hundreds?) and finally try and answer if these were in fact saddle swords, used only on horseback or were they used more on foot? In the book "the sword in the age of chivalry" they make reference to the saddle sword but bring up the point that there is nothing that states how large these swords were. In addition, great swords are depicted as being worn on the belt at times.

Unfortunately, I bring to the table only questions - I have none of the answers.

Don |

Hi Don,

I think you hit the nail on the head. We have focused too much on individual battles, and not on the battle as a whole. I think that the point was made earlier that the environment a fighter faced during an individual duel and a melee was quite different, and hence the demands on the fighter would be somewhat different.

I have read Oackeshott's statements that the war-swords were meant to be used on the saddle, and were so long so that they can provide extra reach. I have to say that I have reservations about this interpretation. From my experience, war-swords really need two hands for good control, and using both hands to hold a weapon on a horse back is not a good idea. There was a recent thread about mounted fighting, and there was quite a dispute as to the use of hands to control the horse.

Most people with experience argued that the reigns were the main means of conroling the horse during battle so letting go of them is a very, very bad idea. I am just summarizing what others said.

Maybe the warriors at the time could wield effectively swords of the size of the baron and duke with one hand, but I have trouble (admittedly I am not of Connans physique). Some lighter XIIa swords (AT Lady Carmen) are much easier to control with one hand but I still rather wield it with both.

About medieval tactics. ......... Medieval warriors did not like following tactics much. So Helen Nicholson says in her pretty good book "Medieval Warfare". The central warfare theory in the middle ages was the widely circulated Vegetius book "De Rei Militari" (sp?) . And even though it was widely circulated and probably read. There are very few examples of an army using Vegetius'es advices. Edward I was somewhat of an exception, if I remember correctly. More importantly the majority of the military class was illiterate, and being able to read and follow theoretical advices was the pinnacle of bing un-cool. Sounds too much like today?!?!

That being said, this does not mean that battles were fought without any thought put into them, but the approaches were decided then and there, as opposed to a carefully planned set of army maneuvers.

Again, think of the composition of the armies: successful maneuvers require drills and practice, possible with professional armies, something most medieval armies were not.

Charles the bold tried to drill his armies before campaigns so that he could apply military tacticks, but that failed him badly, on at least one occasion, due to the speed of maneuvering on the battle field.

It is accepted that warfare was an art even in the middle ages in Europe (H. Nicholson agrees with that), but I am yet to read J.F. Verbruggen's book "The Art of Warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages from the Eighth Century" which is highly regarded.

I think this is somewhat beyond the scope of of the discussion but I thought I'd say something about it.

Alexi

|

|

|

|

|

Felix Wang

|

Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 8:13 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 10 Jun, 2004 8:13 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Alexi, I am sorry for causing any confusion. My discussion of longswords and armor referred to the longsword users' being armored, with the assumption that the most common sidearm (not primary arm) of any opponent would likely be a sword (single-hand, probably). As far as I know, the "grete swerde of war" was primarily a knightly weapon; commoner infantry had spears, later pikes or other complex polearms, or bows / crossbows. Most commoners' weapons required two hands (except a basic shield + spear combination), and I am not aware of any clear documentation of large numbers of infantry carrying war swords. The later styles of longsword were used by the upper class, but in Germany spread to middle class usage (i.e. the Marxbrueder) eventually. Even in the later period, I do not think that longsword usage among the commoners was prevalent. However, the sword and buckler was extremely popular among commoners, into the Renaissance in England. Certainly, in the period of the war sword, most troops could have had swords, although the swords may have been of mediocre quality.

In terms of tactics, I would have to disagree with Nicholson. For one thing, Vegetius was of primary value as a guide to strategy and perhaps some technical areas like making a camp - although that was generally neglected by Medieval generals. Vegetius has nothing useful to say about tactics that a Medieval army could use, primarily because Vegetius only discusses infantry. He considered the infantry of his day as needing improvement, and didn't discuss the cavalry because he considered contemporary cavalry (which, by the way, was close to the medieval usage, relying on the charge with lance and sword) was clearly superior to cavalry of the "good old days" of Rome.

The fundamental strategic approach of most medieval commanders was Vegetian - and this was not appreciated by the first historians of medieval warfare (Oman and Delbruck) who themselves thought in Napoleonic terms. That is how Henry II Plantagenet could rule and defend the Angevin Empire throughout his long life without ever fighting a major battle. Vegetius' advice is to avoid battle unless you have a clear advantage, as battles are unpredictable events. He prefers to rely on devastation and sieges - hunger is biologically controlled and hence pretty predictable, and sieges are at least more predictable than battles. The great William Marshal seems to have only fought in two major battles in his career. (for another case, see Gillingham http://www.deremilitari.org/resources/pdfs/gillingham3.pdf ) The chevauchees of the HYW are part of the same strategy - both Poitiers and Agincourt were fought because the French caught up with the retreating English, and forced a battle (which was disastrous for the French). Even warfare in a place as remote and backward  as Ireland had distinct and logical strategic plans ( see Sims http://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/PDFs/simms.pdf ) as Ireland had distinct and logical strategic plans ( see Sims http://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/PDFs/simms.pdf )

However, tactics most definitely existed; although the execution of these tactics did vary with the discipline of the army and the uniformity of command. For a discussion of the HYW - both the archetypal English battleplan and the French responses, read Bennett ( http://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/ARTICLES/bennett2.htm ). During the Crusades, the march of Richard Lionheart down the coast to Arsuf was meticulously planned, with clearly defined detachments of soldiers to perform clearly defined roles. Even though the climactic charge was not ordered by him, Richard had organized his forces well enough that the spontaneous charge was properly supported and turned into a decisive blow. For the organization of the Templars (and some discussion of tactics) see Bennett again ( http://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/ARTICLES/bennett1.htm ). We do know exactly how the Crusader troops were deployed at Jaffa - a row of spearmen in front, kneeling, with crossbowmen them and loaders behind the bowmen; with the few mounted knights left held behind the line in a reserve. Marshall discusses the shortcomings of the knightly charge, http://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/PDFs/MARSHALL.PDF , but it is clear that the charge didn't always work, but when it did, it was because it was carefully controlled. The great stumbling blocks of medieval battle plans were disunity of command and the lack of permanent organization.

Verbruggen is not an exciting writer, but it is an essential book to read. Medieval small unit tactics are difficult to grasp, but cohesion seems to have been the main thing, and that translated into keeping the men close together. If you look at the sources, the tightness of formations is often emphasized, i.e. "you couldn't throw an apple into the men without hitting one". These tight knots of men probably limited the handling of their weapons - for example, a spear used alone as in Chinese martial arts is a two-hand weapon, and both ends are used, and you need room to spin or flip the spear around. Neither a Greek phalanx or a Viking shield wall permits that kind of spear-handling. Dave mentioned skirmish lines, which were a 19th century invention (or at least became popular then). Going back as close to the Middle Ages as we can (i.e. the musket / pike era) when tactics were clearly spelled out, there is nothing like a skirmish line - the men are pretty much shoulder to shoulder, and the horsemen knee to knee (at least ideally). The idea of giving each cavalryman room to swing his saber in a full horizontal moulinet simply wasn't done.

Thus, as far as swing an Atrim longsword (of which I have four), most of the fancy stuff was probably restricted to judicial combat, individual challenge combat, or the beginning / end of a battle when the formations were loosened. The war sword was most likely wielded up and down from a horse's back, with one hand. Against infantry, the weight and power of the sword, combined with the height advantage of the rider, would make it a very lethal weapon. Against other horsemen the weight and power were still effective, and may have made more fancy techniques like the meisterhau unnecessary. (?)

|

|

|

|

|

Allen W

|

Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 6:58 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 6:58 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

Felix your link for William Marshall actually describes William the Conqueror.

|

|

|

|

Alexi Goranov

myArmoury Alumni

|

Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 8:15 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 8:15 am Post subject: |

|

|

Hi Felix,

You are making some good points, but I do not think that they contradict H. Nicholson. Limited strategy and tactics were employed during battles but the arguments is that they were limited, limited in comparison to Roman or Napoleonic battle strategies. There is no doubt that there were organized lines and that the battle followed some logic. My favorite example is the English strategy during the HYW: fight dismounted, hold strong defensive positions and let the archers do the work/damage. Because of the simplicity of the battle plans, which appear to be mostly dictated by the context of the particular battle, the existence of the "Art of War" in medieval europe was dismissed for a long time. Now, I think we both agree, there is resurgence in literature and historians that believe otherwise.

Just to make it clear: H. Hicholson is not arguing that no thought was put into battles, or that there was no organization.

She agrees with the fact that battles were mostly avoided because of their uncertainty. Her argument, as I understand it, is that MOST of the time the plans were very short term. And the organized army maneuvering was limited, and not quite subject to control, due to lack of drilling.

This is not always the case. There were few great generals who thought in long term campaign goals and strategies. But this is the exception and not the rule.

Your favorite examples come from the monastic orders. The caveat is that these guys were PROFESSIONAL soldiers. They spent a lifetime training to fight in formation, they have the experience to do so when it matters. The Templars won everybody's respect during the 2nd Crusade by showing their superb discipline and fighting skill.

I cannot easily project the Templars' fighting ability onto any group of peasants who are fighting because they are paying dues to their land owner. These guys are NOT professionals, they might have never fought before, and their morale and discipline were possibly not even close to that of the Templars

The mounted charges of the knights are more organized because of the knights experience, but I do not think that they were as good as the monastic orders' cavalries.

The point you make about the disunited leadership is excellent. There are no better examples than some of the Crusades.

All in all I think we are saying pretty much the same stuff.

As far as the use of the long sword: maybe it was meant to be used on horse back with one hand , maybe it was used by infantry in tight formations, maybe it was only a knight's weapon. I do not know if there is enough convincing evidence to prove or disprove one or the other.

Cheers,

Alexi

|

|

|

|

David McElrea

|

Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 11:57 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 11:57 am Post subject: |

|

|

Elling Polden wrote: | Quote: | | I belive there are a number of depictions of fighting scenes from the 13th and 14th century where kinghts in single combat have slung their shields on their backs, and are grasping their swords with both hands... |

Such an illustration can be found in the Alphonso Psalter (formerly called the Tenison Psalter)-- it can also be seen in Oakeshott's "The Sword in the Age of Chivalry", page 45 of the 1997 edition.

There are a few other illustrations that touch on some of the views presented here.

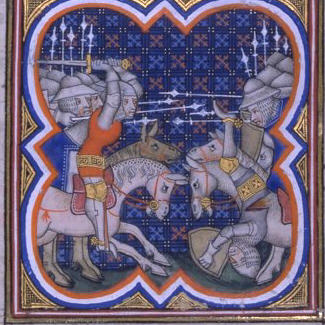

With regards to fighting with a two-handed weapon from horseback-- it can be seen in medieval illuminations. We also know that a "military hallmark" of most horse cultures throughout history was their use of the bow while mounted (and at a full gallop). This doesn't seem unlikely at all to me-- it happened in other cultures and the relevant medieval prints illustrate it.

Illustrations also show the use of two-handed striking weapons by infantry on the battlefield-- swords, axes, and so on. I'll leave off with some of the illustrations I have referred to.

Attachment: 31.75 KB Attachment: 31.75 KB

Note that every one present is wielding a two-handed weapon. No shields here, although it is a battle scene.

Attachment: 66.36 KB Attachment: 66.36 KB

Again, note that the closest horseman is striking with a two-handed blade.

Attachment: 35.7 KB Attachment: 35.7 KB

Another horseman, this time fighting with a two-handed axe.

|

|

|

|

|

Felix Wang

|

Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 6:50 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 11 Jun, 2004 6:50 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Allen, you are quite right. I neglected to mention William the Conquerer in my post; but the analysis of his campaigns fits the same general mold. Hastings was an exception, rather than a typical campaign. Actually, Gillingham has articles about Richard I and William Marshal also ( http://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/ARTICLES/gillingham.htm ).

Alexi, if Nicholson is arguing that Medieval commanders didn't think in the long term, I must disagree. (By the by, when you said "very short term", I assume we are talking about less than one campaign season. ). The general strategic style was Vegetian, which by definition is an attritional strategy. This is always long term. Devastating crops for one season is a problem, but having your fields devastated for 5 or more years running (for example) may cause serious problems. Using sieges to gain territory rather than fighting the enemy in the open field is a slow business, but sieges were the usual Medieval method. If you read Vegetius or Maurice's Strategikon the preference for a slow, secure victory over a quick, chancy victory is crystal clear. I should add that both of these authors were of the (late) Roman Empire and its eastern continuation; Roman strategy was by no means always battle-seeking.

You are quite right, I was looking at the better trained type of troops when discussing tactics. I think this is normal for assessing any military system - in evaluating WW II era armies, taking the Italians as the standard of military skill is vastly misleading. Taking the best troops - paratroopers and elite tank units - for discussion gives a better idea of how the system was supposed to work.

I will object to discussing medieval infantry as a bunch of peasants grabbed off the farm, though. Some systems did rely on mass employment of commoners - such as the Flemish urban militias and the Swiss, and to some extent the Scots. The first two definitely trained their soldiers regularly, and all three had striking successes against knightly armies. What is harder to find - and I would like specific examples, if possible - is cases were the foot soldiers were untrained and undisciplined peasants, and where these men were important combat troops. Such men always existed to support the fighting men, and they sometimes got caught in the fighting and slaughtered, but the commanders were not relying on their stableboys, wagon drivers, and cooks to win.

(you are right, we are in general fairly close  ) )

|

|

|

|

Stephen Wittsell

Location: New Glarus, WI. Joined: 17 May 2004

Posts: 12

|

Posted: Sat 12 Jun, 2004 12:27 pm Post subject: Posted: Sat 12 Jun, 2004 12:27 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Alexi Goranov wrote: |

I have read Oackeshott's statements that the war-swords were meant to be used on the saddle, and were so long so that they can provide extra reach. I have to say that I have reservations about this interpretation. From my experience, war-swords really need two hands for good control, and using both hands to hold a weapon on a horse back is not a good idea. There was a recent thread about mounted fighting, and there was quite a dispute as to the use of hands to control the horse.

Most people with experience argued that the reigns were the main means of conroling the horse during battle so letting go of them is a very, very bad idea. I am just summarizing what others said.

Alexi |

Hey Guys,

My knowledge of medieval fighting techniques is sketchy at best though I'm learning more all the time thanks to threads

like this one. Knowing a bit more about horses I'd like to add this comment. IMO a war horse not trained to respond to the leg would be virtually worthless in battle. Properly trained, it should be able, (should being the operative word) to be guided

through directional pressure from the legs, shifting of weight in the seat and overall bodily attitude and position. Horses are very sensitive to these types of cues as any modern rider can tell you. In fact, they would also be trained to strike with iron shod hooves, both fore and aft. and to savage with the teeth as needed. All in all, an awesome weapon in their own right. So, laying about with a two handed warsword from horse back, as shown in the pictures from David's post, is entirely

practical.

What I am wondering about the use of these weapons by infantry is if they were ever used to initially take out the legs of

charging horses and then dropped in favor of less cumbersome weapons when the armoured knights were then left in the unenviable and vulnerable position turtling around in the mud?

Steve

There are very few personal problems that cannot be solved through a suitable application of high explosives.

|

|

|

|

|

Felix Wang

|

Posted: Sat 12 Jun, 2004 12:46 pm Post subject: Posted: Sat 12 Jun, 2004 12:46 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Steve,

I believe you are right about attacking the legs of horses, although I can't put my finger on an example at the moment. I know it wasn't a standard tactic across Europe, so there must have been some drawback. I would guess this is one reason for maintaining the tight cohesion of a cavalry charge. If the horses are close packed, then there would be no chance for an infantryman to move aside while crippling a horse - he would move right into the path of another horse. I am not certain that attacking the legs of a horse directly in front of you would work, unless it brought the horse to a dead halt. A wounded horse might still lurch forwards, and having a wounded horse fall on top of you might be uncomfortable. The same applies to dropping to the ground and stabbing the horse from underneath. One of the very few cases in the Napoleonic Wars when a square was broken by cavalry happened when the rider was killed, the horse wounded and fell forwards into the infantry. The thrashing around created a hole in the infantry line of the square, and the infantry were routed.

|

|

|

|

Alexi Goranov

myArmoury Alumni

|

Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 10:49 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 10:49 am Post subject: |

|

|

Several random remarks.

If the war horses were fully capable of being maneuvered without the use of reigns, why put reigns on them in the first place?

The illustrations from the Maciejowski bible are filled with depictions of questionable factuality. According to these images one can slice cleanly through chain mail with a "sword-like thing", or split a helmet in half with one handed sword. I think that is pretty much fiction. Let me say that the purpose of these illustrations was not to show to us how battles were fought in reality.

So I think we have to be careful about how much we read into these illustrations. If there were other sources with the same type of depictions (hopefully more representative of the actual period reality) that will greatly strengthen the point.

Felix, from what I understand the compositions of the armies changed through the centuries. In the beginning of the feudal period the farmers (or people how worked the land owned by others) owed a fief tax to their land lord which was most often payed in terms of military service. The length of service was ~4months or less. The lords which extended their campaigns over 4 months were in danger of their army disintegrating as the people payed their "tax" and there was no other obligation keeping them there.

As it is obvious this type of army recruitment is not great but it is largely FREE (no payments involved). In later days, I do not remember exact years, the system changed and now the people could pay in money their annual fief tax, or could still serve or provide an able body to serve for them. With the monetary income the king/local baron could afford to hire more professional soldiers. Now the armies, I think, became more professional as the soldiers were often payed, mercenaries were hired, etc. This situation is closer to the army you are describing. These changes did not happen simultaneously through out europe, so it makes it harder to pinpoint dates and years.

One last thought regarding raids, Chevauchees (sp?) as they were often called. They not only served as a great way to debilitate the opponent, but were also as means of acquiring loot and food. Often an essential activity as food provisions were not adequately provided by the king. And greed is, and always has been a major driving force behind small and large scale military activity. My argument is that passing raids were not done because Vegetius thought them so, but because of necessity and greed. I am not arguing that all raids were like that , just that many or most of them. At any rate, it is very hard to impossible to establish intent. But we both agree that raids were a common military activity.

Interesting discussion, completely outside the scope of the original post but still interesting

Alexi

|

|

|

|

David McElrea

|

Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 2:05 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 2:05 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Hi Alexi,

You wrote: | Quote: | The illustrations from the Maciejowski bible are filled with depictions of questionable factuality. According to these images one can slice cleanly through chain mail with a "sword-like thing", or split a helmet in half with one handed sword. I think that is pretty much fiction. Let me say that the purpose of these illustrations was not to show to us how battles were fought in reality.

So I think we have to be careful about how much we read into these illustrations. If there were other sources with the same type of depictions (hopefully more representative of the actual period reality) that will greatly strengthen the point. |

I am in agreement with you that the portrayal of helms being cloven in two etc. should probably not be taken too literally. Since this was discussed on another thread I have observed the same kind of imagery in numerous other illuminations (I have included an image from the Kulturhistorisk Museum in Bergen as an example).This suggests to me that these types of images are simply an artistic device used to show "which side is losing"-- you will note that the carnage is normally very one-sided. What does this mean for this discussion? I would suggest that it means we need to be less quick to judge Maciejowski as an unreliable source for these discussions. Rather than seeing him as a fantastical (and therefore irrelevent) illustrator we should respect the device and then note what he has to say about weapons, armour, and so on.

Moreover, in my post above I said: | Quote: | | There are a few other illustrations that touch on some of the views presented here. |

I should have said that these images (of two-handed weapons usage in mounted combat) can be seen in a number of illuminations. In including only Maciejowski I may have confused the issue. The same thing can be seen in the work of other artists as well. I will include some of these below.

I note that most of the knights in these images have single-hand weapons and shields (although I have cut them down to details). One occasionally sees, in the midst of the fighting, someone with a two-handed grip on axe or sword. To me this seems perfectly realistic—such a fighting style was obviously not the norm, but apparently it wasn’t unheard of. I find it unlikely that all of these illustrators were clueless about what kind of weapons a knight fought with (and how they fought with them).

You also wrote: | Quote: | | If the war horses were fully capable of being maneuvered without the use of reigns, why put reigns on them in the first place? |

It is not necessary to postulate that they were "fully" capable of being maneuvered without the use of reins-- just that they were capable of being maneuvered in the right circumstances. I have discovered that, within certain limits, it is possible to steer a car with the knees (note that I am not actually admitting to doing so  ). This does not mean that, with respect to driving, knees and hands are equal in every way. In the same way I think the ability to give some direction to your horse through the legs doesn’t mean that reins are thereby redundant. At the charge, with lance couched, I suspect I would be very comforted by the feeling of the reins in my hand. On the other hand, in the thick of the battle where the degree of movement is a bit more restricted the idea of guiding a well-trained horse through the application of pressure seems quite possible. ). This does not mean that, with respect to driving, knees and hands are equal in every way. In the same way I think the ability to give some direction to your horse through the legs doesn’t mean that reins are thereby redundant. At the charge, with lance couched, I suspect I would be very comforted by the feeling of the reins in my hand. On the other hand, in the thick of the battle where the degree of movement is a bit more restricted the idea of guiding a well-trained horse through the application of pressure seems quite possible.

Again, I point out that other cultures used the horse in this way…the Japanese, the Arabs, the Alans and Huns—all of these cultures could manage a horse while wielding weapons two-handed (be they lance, bow and arrow, lasso, or sword). I wonder why, given medieval illustrations of two-handed combat, we find it so hard to believe that European fighters were capable of this feat (even if those with the skill were few, as suggested by the illuminations)?

David

Attachment: 86.11 KB Attachment: 86.11 KB

Might the widespread use of this kind of imagery suggest an artistic device?

Attachment: 39.32 KB Attachment: 39.32 KB

Note the good two-handed grip.

(Battle of the Fords of Saint Clement-- 100 Years War)

Attachment: 15.16 KB Attachment: 15.16 KB

Wielding two-hand axe, possibly swordsman on left using two-hands, as well, but hard to make out.

Attachment: 12.1 KB Attachment: 12.1 KB

One-hand grip on longsword, but no shield-- suggests that armour and skill could be a sufficient defense?

|

|

|

|

Alexi Goranov

myArmoury Alumni

|

Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 4:33 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 4:33 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Hi David,

The additional illustrations do add more merit to your point. I missed your statement in the first post about the presence of such other illustrations. Sorry!

I completely agree with the point that these illustrations aim to show that one side is winning over the other, and not to necessarily reflect the exact reality of the battle.

You mention that other cultures have used dedicated two hand weapons (bows) on horse back. I am aware of that. The reason I did not jump to the conclusion that swords can be used with two hands on horse back as well is because the battle context is different. The archers ride by the opponents, release several flights of arrows and retrieve (just guessing). The melee combat seems to be a different ball-game. I would not necessarily say that it is easier or harder to control galloping or melee fighting horses without hands. I have no experience in that department. But since the battle contexts seem different, I cannot logically make any strong claims.

There also are experienced riders and reenactors who seem to think that the reigns were essential for controlling the horse in melee combat. It is also worth mentioning that there are experienced people that disagree.

An almost universal truth seem to be : "make a statement and I will find you a person who disagrees with it".

My whole point in the last few posts was that absolute statements need to be avoided when possible, since there is no enough clear cut evidence. David, I do not think that you were making absolute statements. You were just defending the possibility of fighting a certain way.

Could one ride a horse and wield a weapon using two hands. SURE!!!! How often and how successfully? I do not know!!!!!

I do have a personal opinion, not based on much evidence I must admit. That is where discussions like this one become useful. The experts (read historians) are also very often biased and prejudicial, hence basing all opinions on only few books is also dangerous.

Unfortunately I think there are many such issues and questions that cannot be simply answered either due to lack of direct evidence or because the issues themselves are quite complicated. So arguments (not in the negative connotation of the word) are the way to resolve/ reach an interpretation of an event or question. (Don't you wish I never took several years of philosophy  ) )

Cheers,

Alexi

|

|

|

|

David McElrea

|

Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 4:43 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 13 Jun, 2004 4:43 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Well said, Alexi.

While we may lean in different directions on this issue, I think we are agreed on the methodology that is best used to approach the issue.

Cheers  , ,

David

|

|

|

|

Elling Polden

|

Posted: Mon 14 Jun, 2004 12:46 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 14 Jun, 2004 12:46 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Ta-TA! I'm back from the void...

I'll try to answer the questions posed to me in my absence...

On reenactors and footwear:

I can only answer for my scandinavian coleagues, but we do a bit of both, depending on weather and the nature of the arangement. Personaly I preffer modern boots.

Due to safety reasons we rarely crash into each other full force, wich is a problem when it comes to realism, as large scale medevial combat would be as much a brawl as a swordfight.

The conclusion is that we can fight pretty accurate duels, but battles are harder, due to the nature of field combat, and the lack of personell. (the largest scandinavian gatherings have 2-300 fighters.)

It does however show some of the efficiency of different weapons.

My previously proposed "food chain" is not a natural law of any kind, but rather the tendency we see. It is of course posible for a longswordman to beat a Sword/shield fighter, but the ods are against him.

When it comes to the use of warswords from the sadle, do remember that is also quite posible to use a warsword in one hand!

Agreed, they are heavy and sluggish when used one handed, but for the amount of finesse in knigth vs footman fighting is limited at best. (chop 'im in the head. If he blocks, ride him down. If he runs, hit him again, then ride him down.)

The weapons later used for this kind of work include maces and flails, who are also used in a similar, no-nonsense way.

Yours

Elling

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2024 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|