|

|

|

Jeff Helmes Type XII Korsoygaden Sword

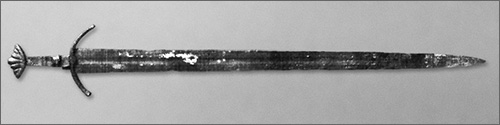

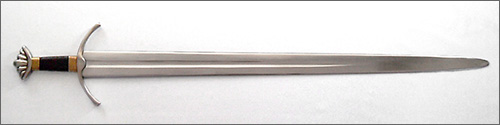

A hands-on review by J.D. Crawford If one thinks of a Viking sword one will likely picture a broad-bladed slashing sword with a compact hilt and wide flat pommel, while the mention of a High Medieval sword will likely conjure an image of a larger, longer-bladed weapon with a simple cruciform hilt and perhaps a disc-shaped pommel. However, history did not proceed along such neat categorical lines. For example, Dr. Jorma Leppäaho (as quoted by Ewart Oakeshott) unearthed various knightly cruciform swords amongst late Viking era burial sites in Finland. Conversely, "Vikingesque" lobated pommels persisted in period art depicting knights in battle well into the 13th century. Weapons that possess characteristics of both the Viking age and Medieval era have sometimes been called transitional types. Perhaps the best known of these transitional types is a family of swords mainly associated with Northern Britain. This family of one-hand swords possesses Oakeshott Type M pommels (five lobes, the center one longest over a vestigial curved upper guard) and a cross-guard or lower guard that curves strongly toward the blade. The overall impression is that the hilt developed from earlier Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian types though the blade is clearly of medieval type, characteristically Oakeshott's Type XII. Such swords are depicted in Northern English, Southern Scottish, and Irish grave slabs dating to the early medieval period, and persisted (in somewhat modified form) in Western Highland grave slabs of the 13th-15th centuries. The few surviving representatives include the celebrated Cawood sword (found near Cawood Castle in Northern England), and a very similar, but larger sword found in the coastal Korsødegården region of Norway. Likely owing to an early misspelling or mis-translation, the latter has unfortunately come to be known as the Korsoygaden sword in English writings. Oakeshott believed these two swords came from the same workshop or even the same hand, but at the very least there is a high stylistic similarity that may owe to the close connections between Norway and northwestern Britain through the Middle Ages. The Cawood sword is perhaps better known to the English-speaking world, but it is the Korsoygaden sword that inspired the focus of the sword featured in this review. Overview The original Korsoygaden sword is currently housed in the Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, Norway (view the online photo gallery). Based on the style of runes inscribed in one of the bronze collars that surrounds the grip, this sword (and thus others like it) have been dated to the first half of the 12th century. The Korsoygaden sword is a large weapon, with a broad blade nearly 35 inches long. Oakeshott classified it as Type XII (XII.10 in Records of the Medieval Sword), but most of the blade profile is actually quite parallel like a Type XIII(b), only curving very near the end toward the more acute tip associated with Type XII. This sword was found in a state of excellent preservation in 1888 within a stone cist along with remnants of a scabbard and a buckler-sized round wooden shield. One cannot say how it was buried thus, but given the epoch, cross motif on one surviving piece of scabbard, and lack of human remains it is clearly not a pagan burial site. One might imagine that the owner died far from home in one of the early crusades, and his comrades brought his weapons home for surrogate burial, but this is pure fancy on this writer's part.  Original Korsoygaden sword housed in the Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, Norway The subject of this review is a custom replica of the Korsoygaden sword commissioned from Jeff Helmes Bladesmith. Jeff is an emerging talent who has specialized at the time of this writing in Viking-era swords and knives. He has done some fine work with pattern-welded blades and decorative inlay, notably in collaboration with Michael Pikula. After spotting his work through myArmoury, I decided to commission a medieval monosteel blade to suit my interests and budget, so the transitional Korsoygaden sword—long on my wish list—was the perfect intersection of our interests. Given that this was Jeff's first foray into a fully functional and finished battle-ready medieval era sword, he was willing to accept my detailed specifications, and was also very forthcoming with verbal and pictorial feedback of the process (see this myArmoury.com forum topic), resulting in numerous and pleasant e-mail exchanges. Nevertheless, the completed sword and custom-made scabbard (packed in cut-to-fit Styrofoam within a very robust custom wooden case), arrived at my home less than two months from the commissioning of the project. Some production versions of this general type are available: Depeeka and Arma Bohemia carry shorter-bladed versions of the sword, CAS Iberia / Hanwei has recently come out with a replica of the Cawood sword, Del Tin Armi Antiche has its version of the Cawood sword that can be ordered with a longer blade more like the Korsoygaden sword, and other custom makers have done various versions of the Cawood sword. The out-of-production Windlass Steelcrafts Transitional Viking sword had characteristics of both swords. However, to this author's knowledge, Jeff Helmes' version is the first serious attempt to capture the size, spirit, and details of the historic Korsoygaden sword.  Measurements and Specifications:

Replica created by Jeff Helmes Bladesmith of Ontario, Canada. Handling Characteristics This is a big sword and its short grip and pommel type do not allow the use of a second hand. It is simply a big, one-hand early medieval cutter. The length and width of the blade, along with its extended (but historically accurate) point of balance, announce a sword with a great deal of blade presence. However, for someone who appreciates such swords, this example is a joy to wield. Jeff has done an admirable job of keeping the overall weight down (indeed lower than many smaller swords on the reproduction market), and at optimizing the mass distribution. The blade is relatively thin overall (ranging from 5mm at the guard to just above 2mm near the tip), and its non-linear (concave) distal taper puts most of its mass near the hand. The result is a sword that is manageable and excels in motion, but does not want to stop once it's in motion. This is by no means a fencing sword by late medieval standards, and will resist attempts at finessed wrist rotations. However, I have run the sword through a number of fencing drills from the later medieval era and found that despite the need for some extra torque to get it moving and stopped at guard positions, it's manageable without discomfort.

The pivot point of the sword is quite near the tip so it's not hard to aim the point in a thrust, but other factors—the weight and length, the point profile, and the flexibility of the blade—mitigate against it being a highly competent thruster against any sort of armour. Not surprisingly, the long thin blade is quite flexible, and droops slightly when held horizontally, but not to the point of being "whippy". The edge of the blade is fairly sharp and well integrated with the lenticular blade cross-section (except at the forte where it becomes more chisel-like). With winter coming on in my region at the time of this writing I have not had opportunity to get outside and do any cutting, and likely will not do so in order to maintain it in as-new condition. However, the size, width, profile, and thinness of the blade promise massive cutting power. The flexibility of the blade might dissipate some of this energy if not struck at the distal harmonic node (center of percussion), but the proximal harmonic node is at the guard, so this should not lead to undue discomfort or wear on the hilt components. One can easily imagine the original Korsoygaden sword, with its reach and design, being used as a cavalry weapon, dealing great sweeping blows from the back of a warhorse. However, there is historical evidence that large one-handed swords like this were used in the 11th-12th century by large, well equipped infantry (see Oakeshott's Sword in Hand; chapters 8 and 9). In this case, likely in combination with the buckler found with the sword. Fit and Finish Jeff Helmes' dedication to historical accuracy shows in both his methods and results. For this sword he used traditional methods of forging the blade blank and edges, followed by grinding and hand polishing. The pommel/upper guard were made in two pieces through forging and filing, and then peened, along with the cross/lower guard, directly the blade tang rather than relying on pressure against the wooden grip core. The latter was wrapped in traditional fine hemp before the final addition of reddish brown leather, bound in two decorated bronze collars like the original sword. The result is a very solidly constructed piece that captures the overall dimensions, spirit, and details of the original.

A conscious departure in historical accuracy came with the Runic inscription on one of the bronze collars, which originally read "Asmund made me, Asleik owns me" (in old Norse). As a judgment call, this author decided it might be less accurate but more honest to replace this with "Jeff (Iefr) made me, Doug (Dugr) owns me". Rather than doing this in English with generic runes, Jeff enlisted the aid of noted author, historian, and runologist Stephen Pollington, who determined the correct form of runes from the original, then translated our modern names and phrase back into the correct period language and runes. According to Pollington these runs are of a variety used in Iceland and Western Norway in 1150, thus adding further refinement to our knowledge of the historic sword. In terms of overall finish, the sword is beautifully detailed from pommel to tip. Although I generally prefer a high polish, Jeff insisted on a satin finish that he could produce by hand using a level of grit known to exist in-period. The blade edges and fuller are even and symmetric to the eye from every angle, the fuller fading toward the tip into a flat lenticular blade (unlike even some of the better production replicas of this era). The fuller edges are crisp, although not quite so ultra-crisp as high-end production pieces made using modern technologies. The peen is clean, the pommel lobes are finely shaped, and the pommel fits cleanly against the separately made upper guard. To find imperfections one must really hunt: a few irregularities in the recess of the cross, a slight scrape near the edge close to the cross that could easily be removed through polishing (i.e, minutia). Overall, one supposes this sword could have been produced next in line after the original Korsoygaden sword, or more likely several down the line after that ancient bladesmith had further perfected his craft to the level of this modern reproduction.

Conclusion In this author's opinion, Jeff Helmes Bladesmith has produced a majestic sword that more than does justice to the original Korsoygaden sword. Jeff and I both learned a great deal about such swords in the course of this project, perhaps even contributing to the scholarship of this particular sword. In terms of handling properties, historical accuracy, and finish, this large sword easily ranks amongst the best high-end production pieces and custom pieces in my own collection. All things considered—Jeff's traditional methodologies, this being his first completely functional medieval sword, and the short timeline—I am pleased, to put it very mildly, that the first attempt turned out so well. I expect we will be hearing and seeing a lot more from this emerging bladesmith in the future. About the Author J.D. Crawford is Professor and Canada Research Chair of Visuomotor Neuroscience at the York Centre for Vision Research, Toronto. He has had a hobby interest in military history and weaponry, primarily the development and use of the sword in early Medieval North-Western and Central Europe, since childhood. Acknowledgements Photographer: J.D. Crawford J.D. Crawford and Jeff Helmes thank Stephen Pollington for his aid in interpreting/translating Runes from the original Korsoygaden sword and for the modern replica described above. Sources Records of the Medieval Sword, by R. Ewart Oakeshott Sword in Hand: A History of the Medieval Sword, by R. Ewart Oakeshott |