Arms, Armour, and Fine Arts

An article by Peter Kren

Fig. 1—Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Judgment of Paris, 1515

|

From the beginning of time, man has had a special relationship with arms, for they have been closely tied to his very existence. With his weapons he captured life-sustaining nourishment and protected his family, his people, and, indeed, his species, when their well-being was threatened. As a result, he associated many of the noblest expressions of human life—power and strength, bravery and self-sacrifice, loyalty and solidarity—with his arms. Over time, weapons assumed ideal and symbolic values above and beyond their material function. Homer described the tradition of preserving a weapon as a souvenir, a trophy, or an offering; as the legitimization of a claim; or even as a collectible object. Due to this urge to protect the souvenirs of important struggles, men preserved armaments in ecclesiastical, dynastic, and secular treasuries. One of the great historical European arms collections, the Landeszeug-haus, or the Styrian State Armoury of Graz, was saved from dissolution thanks to a conviction to preserve these arms and to document Styria's military achievement.

From the beginning of time, man has had a special relationship with arms, for they have been closely tied to his very existence. With his weapons he captured life-sustaining nourishment and protected his family, his people, and, indeed, his species, when their well-being was threatened. As a result, he associated many of the noblest expressions of human life—power and strength, bravery and self-sacrifice, loyalty and solidarity—with his arms. Over time, weapons assumed ideal and symbolic values above and beyond their material function. Homer described the tradition of preserving a weapon as a souvenir, a trophy, or an offering; as the legitimization of a claim; or even as a collectible object. Due to this urge to protect the souvenirs of important struggles, men preserved armaments in ecclesiastical, dynastic, and secular treasuries. One of the great historical European arms collections, the Landeszeug-haus, or the Styrian State Armoury of Graz, was saved from dissolution thanks to a conviction to preserve these arms and to document Styria's military achievement.

Likewise, for nearly as long as there have been weapons, craftsmen have wanted to decorate them. Throughout the history of arms, and reaching a high point during the Renaissance, a man's station, status, wealth, and personal taste determined how elegant and how exquisite his weapons would be. To be sure, a man's arms were an extension of his clothing and a distinguishing sign of his social position [figure 1].

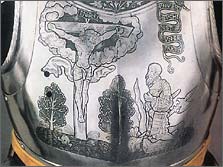

Fig. 2—Close Helmets for the field, 1550-1570

|

Stylistic Affinities Between Arms and Art

Arms were always a part of man's search to embellish his world and to shape his surroundings according to a particular style. The creative energy of an era is as evident in its weapons as it is in other types of fine and applied art. For centuries decoration enhanced even the simplest and most common weapons, but with the mechanical mass production of weapons in the nineteenth century, this idealistic and artistic dimension largely disappeared, and arms became indifferent instruments of war.

Armour and Art History

For many years, art historians overlooked antique weapons in their research, neglecting important historical collections of arms with holdings dating from as early as the fourth century through to the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1936 Bruno Thomas, a distinguished art historian and later director of the famous arms collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, challenged his colleagues to study the field of weapons because there was so much to be discovered from them. In his programmatic essay "Waffenkunde als Kunstwissenschaft" [The Aesthetics of Arms] (Belvedere XII, Vienna 1934/36), he explained that the art historian the Lentner, or cloth-covered armour, which was already fitted to the waist and so emphasized the body, to complete plate armour, developed at the end of the fourteenth century. With its torso armour, its vambraces and leg harnesses, and its corresponding joint connections, plate armour clearly described the body parts and their functions. Plate armour, moreover, corresponded to the realism that was felt throughout Europe in the fifteenth century.

An already well-known and generally accepted relationship exists between the German suit of armour from about 1460 to 1480, richly decorated with ridges, grooves, and points, and the similar details in the work of contemporary German Late Gothic artists such as Michel Pacher (c. 1435-1498) and Bernt Notke (c. 1440-1509), or even of Italian Renaissance painters such as Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435-1488) and Antonio Pollaiuolo (c. 1432-1498). Fluted armour, a creation of the early sixteenth century, is understood as part of the new plasticity of the German Renaissance, seen, for example, in the work of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Hans Burgkmair (1473-1531), and Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543), as well as in the intricate creations of the Danube School artists such as Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) [figure 2], and Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480-1538). The influence of the articles by Thomas and Camber is confirmed by the fact that, after 1945, historical arms were more often included in books on applied arts. Today they are even more readily included in large exhibitions that focus on the historical and artistic periods of a particular region.

Ornamental Motifs on Arms and Armour

Fig. 3—Three Halberds, late 16th century; Boar Spear, 1573

|

Even more clearly than in the basic shape of a suit of armour, a pistol stock, or a halberd head, the style of an era can be revealed through the decorative ornamental details that organize and embellish the object's surface. Factors such as the care of execution, the density of decoration, and the costliness of materials not only reveal the artistic period of a weapon, but also provide clues about the social station of its owner. The elongated form of most edged, staff, and percussion weapons and firearms—derived from the weapons' functions—offered little surface for decoration, but that very shape inspired the craftsman's imagination to create unusual solutions [figure 3]. For example, early Germanic and Scandinavian peoples used animal and wickerwork motifs, common decorations for their houses and ships, to decorate their sword grips and scabbards as well. Later, the architectural feature of Gothic tracery, which delineated the designs of stained-glass windows, was also imitated by craftsmen on maces and for the pierced ornamentation of spearheads, spurs, and stirrups.

Fig. 4—Morion, c.1575, comb decorated with arabesques; abstract moresque-like motifs decorate the skull and brim

|

With the emergence of the Italian Renaissance and the spread of its influence throughout Europe in the sixteenth century, the decoration of weapons developed with particular intensity. Rediscovered antique motifs encouraged artists to invent more extravagant designs. The new and flourishing medium of prints helped to spread these ornamental patterns, whether through individual sheets or entire books on ornamentation. Four ornamental forms that made a triumphant advance in the sixteenth

Fig. 5—Nikolaus Klett, Pair of Wheel-lock Pistols, c.1610

|

century—the arabesque, the grotesque, scrolled decoration, and the Moresque—are all frequently represented on weapons.

The arabesque was usually a symmetric, plastic, and naturalistic foliate tendril used in classical antiquity to decorate architectural elements. Early Italian Renaissance artists adopted this motif, and it was introduced to Germany in about 1520. The arabesque spread further through ornamental prints by such German printmakers as Bartel Beham (1502-1540) and Heinrich Aldegrever (1502-c. 1560). Graceful arabesques were used in different variations as inlay work in the stocks of small firearms. They are also found as embossed decorative motifs on some parade armour of the sixteenth century, where they parallel gold and silver embroideries on garments [figure 4].

Fig. 6—Small prints such as these engravings by Heinrich Aldegrever served as models for craftsmen and demonstrate the influence of the Italian Renaissance on German artists

|

The grotesque is a more fanciful category of decoration that consists of combinations of symmetrically arranged foliate tendrils and various objects such as vases, candelabra, fruits, flowers, trophies, architectural elements, fabulous creatures, and animal and human figures [figure 6]. This ancient form, developed in imperial Rome as architectural embellishment, was discovered there in the Domus aurea of Nero at the beginning of the sixteenth century. At that time, the Domus aurea was still underground; hence this decoration was named after grotta, the Italian for "cave." In 1511-14 Raphael made exemplary use of the grotesque in his series of

Fig. 7—In the early 1550s, Virgil Solis engraved a series of Nine Worthies, including characters of classical antiquity, the Old Testament, and the early Middle Ages. These portraits are framed by scrollwork ornaments and grotesque figures

|

murals for the loggia in the Vatican Palace, but the form of the grotesque remained a favorite motif through the nineteenth century. Ornamental engravers in Italy and Germany have depicted the grotesque since its revival in the Renaissance, and it is found on arms dating to the second half of the sixteenth century. The grotesque's great popularity was in part due to its hybrid nature, which permitted artists and craftsmen working in a broad range of materials and techniques to vary the forms almost without limit. The fantastic diversity and refinement of the grotesque bestows upon objects the impression of heightened splendor.

Scrolled decoration was also in widespread use in architecture, the decorative arts, and graphic art. About 1550, ornamental prints carried scrolled designs from Italy to the Netherlands and Germany. The form's rolled and slotted bands appear on prints as cartouches and volute-like architectural elements that have a sculptural effect [figure 7]. Scrolled decoration, despite its rather unwieldy nature, can be encountered on armours and shields of French and Flemish origin, sometimes combined with the grotesque. Frequently, however, it served as inlay work on the stocks of small firearms, where it found a natural place as a framing or accenting motif, similar to its use on furniture.

Fig. 8—Christoph Jammitzer, Ornamental (Moresque) Band with Initials M A, 1610

|

The Moresque [figure 8] originated from the acanthus, the leaf used so often in antique decoration, but it was transformed in the East into a flat form with intricate surface decoration that became known in Italy in the fifteenth century through Islamic carpets, bookbindings, and glass. It was adopted in Italy and became known through ornamental prints, especially those by Francesco Pelegrino (d. 1552), who after 1530 belonged to the artistic circle at Fontainebleau. In 1546 in Nuremberg, the German ornamental printmaker Peter Flötner (1485-1546) compiled a book of Moresque patterns, which was published in Zurich in 1549 and quickly spread throughout Europe. The silhouette-like, stylized foliate and tendril forms of the symmetrical Moresque were engraved or etched onto armours [figure 9]. The Moresque did not, however, attain the popularity of either scrolled decoration or the grotesque.

Decorative Techniques

Fig. 9—The borders and bands in the middle of this breast- and backplate are covered with etched moresque motifs (third quarter 16th century)

|

In addition to this new wealth of ornamental motifs, there were many decorative techniques that the skilled craftsman employed for arms. Line etching, developed during the late fifteenth century, used acid to assist the graving tool. With this method, the metal surface to be decorated is first covered with an acid-resistant protective medium, often wax, through which the etching needle can easily cut. Then a caustic acid is applied, which works into the exposed parts of the metal. After removing the protective coating, the etched design is blackened, making the design clearly visible. This technique for decorating arms was the precursor of printed etching, for if one were to rub an arms-etching with printer's ink, one could print it on paper.

It comes as no surprise that the discovery of the etching technique, first executed on iron plates and only later on copper or tin, can be attributed to the circle of arms-etcher Daniel Hopfer (c. 1470-1536), who came from a large Augsburg family of arms-etchers and graphic artists. Augsburg was not only an artistic

Fig. 10—Horse Armour (detail), 1505-10: School of Konrad Seusenhofer, etched in the early style of Daniel Hopfer the Elder

|

center for painters, graphic artists, and goldsmiths, but it also produced the best gunsmiths and armourers, including the distinguished armourers of the Helmschmid family. Daniel Hopfer's achievement was widely recognized during his time, and in 1590 he was posthumously named as the inventor of the art of etching in an imperial patent of nobility bestowed upon his grandson Georg. On the whole, scholarship of arms etchings and other figured and ornamental arms decorations is still in its infancy. While Hopfer's contribution as a printmaker is generally acknowledged, his arms etchings are at least as important, and, like his prints, reveal the role that Italian ornamental motifs had on his transformation from a Late Gothic to a Renaissance artist. The etched motifs on the horse armour in the Landeszeughaus, for example, which were created shortly before 1510, show this important transition [figure 10]. Here he mixed intricate and fanciful Late Gothic foliate tendrils with Italianate fruit festoons that are clearly Renaissance in character. Although this armour does not appear in any inventory of Hopfer's work, it is more significant than many of his ornamental prints. In spite of recent advances in the scholarship of arms and armour, the armour decorations of this early Renaissance style innovator still have not been studied.

Fig. 11—Many German and Austrian breastplates from the mid 16th century bear an etched crucifixion-and-kneeling-knight motif. It has been suggested that in some cases these depicted the armour's owner, making a personalized devotional image for a soldier to wear in battle

|

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, craftsmen expanded on the basic technique of etching and developed raised etching. In this variation, rather than the design being the intaglio, or recessed and darkened area, the design remains in slight relief and stands out against a background that is darkened by small etched dots. To accomplish this, the protective medium is applied with a brush to the parts that remain elevated, and is dotted with a quill over the background [figure 11]. In Italy the background was crosshatched rather than dotted, making it possible to identify whether a decoration originated there.

Another technique of introducing a linear design onto the surface of a suit of armour, a shield, a sword, or a gun barrel was damascening. As its name implies, this technique originated in the East (Damascus is the root for the word; the German term is Tauschierung, from the Arabic tausija, meaning "decoration" or "coloring") and is achieved by beating a softer metal such as gold or silver into the harder iron. There are two methods for this. For the first, which was brought from Italy to Germany around 1520 and soon spread throughout Europe, the background surface is roughened with crosshatching. Then precious metal in the form of wire or small sheets is applied and the piece is smoothed to an even surface and polished. The second method is somewhat more difficult. The design is first cut into the iron surface with a graving tool. Gold, silver, or copper wire is then hammered into the recesses, holding the design more securely than in the other method and permitting it to remain raised.

In order to obtain the effect of color, various other methods were also employed, for example, painting with oil pigments or covering with fabric. The iron could also be heated to generate oxidation tints. With this technique, various colors could be achieved, from pale yellow at 220°C to purple at 270°C and dark blue at 310°C. If one wanted the coloration only on certain parts of the weapon, the oxidized surfaces could be removed by etching the metal with dilute acetic acid.

Fig. 12—This armour is decorated with a black-and-white finish, in which the craftsman alternated bright, polished surfaces with unpolished or otherwise darkened areas. In addition, the armour has been embossed, a process whereby the metal was punched and raised from within, producing a design in relief

|

Various gilding techniques were more costly and also more tedious. In leaf gilding, the gold leaf is laid on the freshly varnished iron surface; drying the varnish under pressure adheres the gold. In fire gilding, the metal object is prepared with a copper solution before a gold and mercury amalgam is applied. Heating causes the mercury to evaporate, leaving the pure gold adhering to the metal. The gold-melting and enameling process is similar. For these, the gilded designs are first etched or engraved into the metal.

In addition to these methods of decorating the surface of an object, there were also some that transformed the object more substantially. Such was the ancient technique of embossing, or repousse. It flourished anew in the sixteenth century, especially in connection with the all'antica style of armaments. In this technique, the design is first sketched on the object and is then punched and hammered from the inside to form a raised motif. The Landeszeughaus owns a beautiful example of this treatment in the three-quarter armour from about 1550 by Michel Witz the Younger [figure 12].

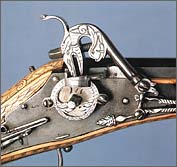

Especially in weapons, iron-cutting and iron-relief engraving facilitated pierced forms and reliefs on metal surfaces. Here, the ground was hollowed out with a chisel and worked with a punch and graving tool. These ornamentations were very common for sword and dagger hilts and were also used on small firearms [figure 13]. Related to this is pierced ornamentation, or fretwork, in which iron is perforated and cut out, a favorite technique in armours of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Cut-out tin patterns, which were applied to pistol stocks and powder bottles, also belong to this category.

Finally, the decorative techniques that flourished in the Renaissance and Baroque eras for other decorative arts were also used to embellish the wooden stocks of rifles, pistols, and crossbows. Most common was bone or ivory inlay, which was used in connection with bone engraving [figures 14, 15]. Almost every small sixteenth-century firearm in the armoury—and there are more than one thousand of them—is adorned with inlay. In this procedure, the design is engraved on a small plaque of bone and blackened. Then a section of wood is removed from the stock to accommodate the plaque, which is glued in place. In a similar method, bone and mother-of-pearl plaques were not only laid into the stock, but also fixed with metal pins.

Fig. 13—Wheel-lock Pistol (detail). The doghead and pierced wheel cover is decorated with engraving and iron-cutting

| |

Fig. 14—This German-type stock is richy inlaid with engraved late Renaissance-style staghorn decoration. The primary motifs are grotesques, foliate stripes, and tendrils; on the reverse are mythological scenes in rollwork frames depicting Perseus and Andromeda, Poseidon and Amphitrite, and Europa and Bull

|

|

Fig. 15—Although the barrel and lock are lost, this long stock is remarkable, for it is the most ornate in the Landeszeughaus. Its lavishy dense and intricate decoration includes tendrils, grotesque motifs, ellegorical figures, and medallions with views of a town

|

The stocks themselves could also be carved from wood or ivory, a technique that demanded great skill. Stocks of small firearms, or even objects such as powder flasks and sword hilts, have been sculpted into fully three-dimensional creations.

Arms and Armour in Art

The representation of battle and armaments in the arts of painting, sculpture, printmaking, drawing, and other media is a nearly inexhaustible subject of study. Such representations parallel human history from the cave paintings of Stone Age man to the depiction of real or fictitious scenes of war and revolution in modern photographs and motion pictures. The greatest artists have created battle images of wide-ranging style and scope, and many of these are among the most outstanding works in the history of art.

In western European culture, the representation of war has had both a mythic and an actual dimension. Phidias, the renowned sculptor of the Acropolis, carved the battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs in the metopes of the Parthenon; the masters of the Hellenistic altar to Zeus in Pergamum showed the gods' tortured faces in the intensely dramatic frieze of the gigantomachia (the battle of giants). The Romans, on the other hand, always more inclined than their predecessors to record artistically the minute details of history, decorated the triumphal columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius with faithful representations of military campaigns. They are now prized as documents of the armaments of the empire and its enemies in the second century.

Fig. 16—Modelled by Leonard Magt, cast by Stephan Godl, Nude Warrior, 1526. The warrior's pose is typical of Italian Renaissance figures, while the slender body and fine detail embody German Late Gothic elements

|

Since Roman times, in fact, the most important representations of arms in art are generally characterized by realism of observation—by what we now would recognize as a documentary impulse. The famous Bayeux tapestry, for instance, records the exploits of William the Conqueror, including his victory in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, as a series of embroidered panels. Created only a short time after the events took place, this lively pictorial narrative is a unique document of the appearance and use of Norman and English armaments of the eleventh century, and modern historians of arms and art alike have cooperated to interpret its significance. Even in devotional images of the Late Gothic period, such as the Votive Tablet of St Lambrecht, c. 1430, or in the panel from the somewhat provincial Miraculous Altar oj Mariazell, painted around 1512 by an artist of the Danube School, the will to record the actuality of arms can be appreciated. Although both paintings were created as images of religious inspiration and propaganda, the weapons depicted and the action of battle help the modern viewer understand the function of armaments.

The development of pictorial perspective by painters of the fifteenth century makes their art particularly instructive to the modern student of arms and armour. Artists as different as the Florentines Andrea dell Castagno (1421?-1457) and Paolo Uccello (1396/7-1475), the Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck (active 1422-1441), and the German Konrad Witz (1410/11-1444/46) treated armaments in pictorial terms that still seem wholly convincing to the modern viewer. Even today we can study their paintings for clues about the history of arms. By the same token, we can compare surviving elements of armour and their representation in contemporaneous works of art—such as the hussar's shield perhaps made in Hungary and a nearly identical shield carried by a soldier in the Danube School panel painting The Legend of St Sigismund, c. 1520, by the Master of the Brucker Panel of St Martin.

Fig. 17—According to legend, St. Florian, the patron who protects against the threat of fire, extinguished a burning church with a single bucket of water. Here he performs his firefighting heroics wearing a transitional form of armour of Maximilian period

|

The representation of armour is not always strictly historical, however. When, about 1515, the German master Lucas Cranach the Elder composed the Judgment of Paris, [figure 1] he considered it entirely appropriate to clothe the sleeping Paris—a prince of ancient Troy—in a faithful representation of a modern suit of armour. (By contrast, the bearded figure of Mercury in the painting wears fanciful armour, combining ancient and modern forms, that Cranach deemed appropriate for a demi-god.) An Italian painter of Cranach's time—Raphael, for instance—would have been more likely to adhere faithfully to an Arcadian tradition, and would have insisted on clothing the Trojan shepherd-prince in a pastoral costume derived from antique statuary or wall paintings. For the German-speaking painter of the early sixteenth century, on the other hand, the association between princely grandeur and arms and armour was taken almost as a matter of course.

It is in the German-speaking world of the Renaissance, therefore, that some of the greatest representations of princely armour can be found.

In 1512 the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I commissioned an ambitious series of woodblock prints and illustrated books to glorify his military achievements and the memory of his family. The works included illustrations to the propagandistic romances Freydal, Theuerdank, and Weisskunig, as well as the many woodblock prints that together comprise the Triumphing (a triumphal chariot and procession), and the Ehrenpforte (a printed triumphal arch that celebrated Maximilian's dynasty). Following the instructions dictated by the emperor, these large and complex prints are overwhelmingly devoted to battle, the tournament, and the hunt, as well as to the diverse branches of arms production and of military science. The list of artists called to this undertaking includes many of the most important printmakers of the Northern Renaissance: along with Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair, and Albrecht Altdorfer, there were Jorg Kölderer (active 1497-1540), Hans Schäuffelein (c. 1483-1539/40), Leonhard Beck (1480-1542), and Jorg Breu (c. 1475-1537). Seldom have painters and graphic artists—even those who specialized in military subjects—come to terms as intensively with the weapons and military apparatus of their time as did the printmakers who worked on Maximilian's extravagant projects. Nor did the need for the exacting representation of such equipment impair their creative imagination. It was truly a lucky circumstance for the emperor that his reign coincided with the greatest period of German art.

Fig. 18—Jost Amman and Tobias Summer, Dess Neuwen Kunstbuchs..., 1570-1580

|

The sixteenth-century proliferation of printed books created a demand for illustrations of all aspects of human endeavor, including illustrations of military figures such as those drawn and engraved for Dess Neuwen Kunstbuchs [New Art Book], by the Swiss-born Jost Amman [figure 18]. An unknown copyist could turn to an illustration by Amman, a woodcut for a manual on courtly tournaments, as inspiration for a lively painting of The Great Tournament in Vienna. In fact, printed sourcebooks such as these disseminated the image of the modern soldier or man of arms to artists and craftsmen throughout Europe.

Thus the Dutch engraver Jacob Jacques de Gheyn (1565-1629) influenced the image of west and central European infantrymen of his time with the magnificent figures of his drill book from 1607. Franz Hals (1581/5-1666) and Rembrandt (1606-1669), with their famous group portraits of civic militia, established monuments to the Dutch soldier and to the military way of thinking. Likewise Philips Wouwerman (1619-1668), in paintings such as his Soldiers in Baggage Train, codified for Europe in the seventeenth century the image of cavalry soldiers at camp in the field—a not infrequent incident in a century dominated by international war.

Of course, this brief survey can only mention some of the ways in which artists have treated the subject of armaments. But it is still clear that fifty years after his pioneering research, Bruno Thomas' challenge to art historians has been embraced. Historians no longer hesitate to approach the subject of arms and armour, for their history is now valued as being integral to that of both art and culture. Indeed, the study of arms and armour has been humanized in the best sense of the word.

About the Author

Peter Krenn is the co-author of Imperial Austria: Treasures of Art, Arms and Armour from the State of Styria. He has graciously granted permission for the republication of this article.

Acknowledgements

Text and photography © Copyright 1992 by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and Prestel Verlag, Munich.

|

|