Renaissance Armies: The Swiss

An article by George Gush

The Swiss established their military reputation, along with their liberty, in the 15th Century, and their victories of the 1470s over the armies of Charles the Bold gained them general recognition as the supreme foot-soldiers of Europe, a reputation which they held until their defeat at Bicocca (1522). Even after that, though a little of their edge had gone, they remained very good soldiers, as their selection by both the Pope and the King of France as bodyguards indicated. The Swiss established their military reputation, along with their liberty, in the 15th Century, and their victories of the 1470s over the armies of Charles the Bold gained them general recognition as the supreme foot-soldiers of Europe, a reputation which they held until their defeat at Bicocca (1522). Even after that, though a little of their edge had gone, they remained very good soldiers, as their selection by both the Pope and the King of France as bodyguards indicated.

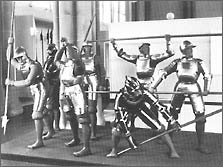

Swiss soldiers in equipment and fighting positions. (Swiss National Museum, Zurich)

|

Mercenary service was a useful supplement to the mountaineer's frugal way of life, and their hirers included Milan, Venice, the Papacy, France, Spain and even Henry VIII of England. In 1516, however, they signed a "Perpetual Peace" with France and from then on were found more or less exclusively in French service; small groups of Swiss were sometimes found in 16th Century Imperial armies, but these were deserters, who showed few of the normal Swiss qualities. For the French, the Swiss formed, as Sir Roger Williams observed, the Body of All Battles, being their chief pike infantry through the first half of the 16th Century, playing the same role for the Catholics during the French Wars of Religion, and they continued in French service through to the Revolution and beyond. In the French army, indeed, the Swiss were not really mercenaries but rather the subsidized troops of a friendly power, and even before this the Swiss, unlike the Landsknechts, were patriotic, would not fight each other, and would go at once to the aid of their Confederation if required (very disconcerting for their employer—like Francis I, who lost 6,000 Swiss this way, four days before the critical battle of Pavia).

Swiss Qualities

The Swiss troops of this period were remarkable both because of the terror they inspired in their opponents, and for their own extraordinary qualities. First of these was sheer courage—no Swiss force of this period ever seems to have been broken or to have run or surrendered; several literally fought to the last man, and the only concession they would make to defeat was a bitter and grudging retreat in good order, defending themselves against all attacks (for example, at Marignano, 1515, where their losses were over 50 percent). Perhaps their habit of hanging the first man to panic had something to do with this!

Secondly, superiority of training: The Swiss relied on a simple traditional system of tactics, practiced until it became second nature to every man, and applied it unhesitatingly under the direction of a sort of committee-leadership of dour and experienced old soldiers—rather like a Roman legion and its centurions.

Thirdly, ferocity: The Swiss spared no-one, refused quarter to their enemies—even prisoners who could afford a ransom were mercilessly slaughtered; they violated terms of surrender given to garrisons and pillaged towns that had capitulated—not a small part of the fear they inspired sprang from this bloody reputation.

With this ruthlessness went a strongly commercial attitude to war—Point d'argent, point de Suisse ("No money, no Swiss") went the saying; if not paid they simply marched off, no matter how that left their employer. If regularly paid they were normally loyal, but there were some examples of their being bribed to change sides. They were also independent and headstrong, their wish to get the job over often leading to attacks without orders, nor would they accept any discipline from outsiders.

a. Swiss halberdier at Pavia, 1525. He wears a Landsknecht-type costume, including a short Katzbalger sword, b. Swiss pikeman at Marignano, 1515. He wears tight striped hose like earlier Swiss, Sallet with face protection, corselet and tassets. c. Swiss armoured pikeman, also at Marignano. He wears a type of Sallet with plumed beret-style cap partly covering it, and half-armour with tassets. d. Swiss Guard, France, 1581. Cap black, pompoms white-blue-red. Doublet: white strip down front; right half red slashed blue, left half blue slashed red. Left sleeve blue with red stripes. Right sleeve white-blue-red, repeated. Forearm: left blue, right red. Codpiece: red-white-blue. Left leg: front blue, red stripes, back probably reversed. Right leg blue-red-blue-white-blue-red-blue. Left stocking blue with red garter. Right stocking white, with red garter and stripe. Shoes black e. and f. Swiss horn blowers from a battle picture of 1512. "e" is Lucerne—horn white, red cord; clothing blue and white with white crosses; red scabbard, "f" is Uri—horn white, red cords; clothing yellow and black with white cross, g. Swiss soldier 1572 with pike and sword, h. Sergeant of Papal Swiss Guard, with glaive, 1517. He wears a garment with baggy sleeves, square cut-away neckline (corselet beneath) and long skirt called a "Sajone" which was worn throughout the first half of the 16th Century by the Swiss Guards

Swiss Tactics and Organization

The Swiss started with eight-foot halberds, but on emerging from their mountains had to turn to the pike to stop cavalry; originally ten foot, the Swiss pikes were enlarged to 18 foot in the early Italian Wars. In the attack they were characteristically held head-high, well forward from the butt, and with the point inclined down.

An actual Swiss halberd of the late 15th or early 16th century showing characteristic shape (Tower of London)

|

Throughout our period the Swiss remained pikemen; many of them were without armour, but front rank men were usually well protected, with open burgonet or pot-helmet, half or three-quarter armour, and often arm protection, including mail sleeves. They formed a deep pike phalanx, with the usual halberdiers guarding the colors and being used if the advance was halted, there were at least ten percent of men with crossbows, or, from the 1490s on, with arquebusses, and these formed skirmishing screens in front or on the flanks of the pikes. When fighting on their own the Swiss used a larger proportion of other types of troops—at Morat in 1476 they had two cavalry to every five firearms, five pikes and five halberds; while when fighting the French in the early 16th Century they had 25 percent arquebusiers and a few cavalry, half of them mounted arquebusiers, and a small number (four to eight) of cannon.

The pikes were normally formed into three very large columns (though at Bicocca there were only two) which could be of equal strength (at Bicocca 4,Q00 each) or widely different, according to circumstances. At Novara, 1513, there was a striking column of 6,000 and two small diversionary ones of 1,000 and 2,000 respectively.

Against infantry, the Swiss nearly always took the offensive; their training gave them tremendous speed—they reckoned to charge artillery between the discharges and they liked to achieve surprise where possible, while the sight of that forest of spear-points coming down at a rush was often enough for the enemy. The columns went forward in echelon, one (not always the right) in advance, the others further back to guard its flanks and act as reserve. Leadership was professional rather than inspired, and the Swiss did not entirely adapt to the growing power of firearms and field defenses; a bloody lesson from the French cannon at Marignano was followed by disaster in the sunken road at Bicocca, 1522.

In French service, regimental organization later developed, and by 1600 the Swiss units were of ten or 12 companies, each of 200 pikes, 30 muskets, and 30 arquebusses.

Bodyguards

The Pope raised a Swiss Guard of 150 in 1506, and it was maintained thereafter except for a short time after the Sack of Rome, later reaching 600 strong. Costume is illustrated; in 1548 they changed to a Landsknecht style of dress.

The French Kings also had Swiss Guards in the 16th Century. Under Henry IV there was a Guard Regiment of 500 and the "Cent Suisses"—100 halberdiers. One of the latter, from 1581, is illustrated, together with a 17th Century Cent Suisse standard.

Dress

Pictures of Swiss troops of the late 15th Century usually show Sallet or pot-helmets, half armour, and simple clothing with tight-fitting hose—often striped or parti-colored—and tunic; the white cross was worn as a field sign—sometimes, apparently on the leg.

In their wars with Charles the Bold of Burgundy, the Swiss are said to have originated the Landsknecht style of dress with its characteristic slashed decoration; after their victory at Grandson (1476) the Swiss patched their ragged clothing with captured silks, and the result was copied by the German mercenaries, who after all were modeled on the Swiss in most other respects. It certainly appears that a style of dress very similar to that of the Landsknechts, if a fraction more restrained, was characteristic of the Swiss in the 16th Century.

Sixteenth Century Flags

a. Confederation flag, red and white, already in use in the 15th and 16th Centuries, b. Zurich—blue and white, c. Zug—blue and white, d. Lucerne—blue and white, e. Fribourg—black and white, f. Unterwalden, Solothurn—red and white, g. Schaffhausen—yellow with black ram. h. Uri—yellow with black bull, red ring and eyes, i. Appenzell—white with black bear, red tongue, j. Berne—bear black on yellow, tongue and corners red

k. Basle—white with red crozier. l. Basle, as seen at Marignano—yellow with red crozier. m. Glarus—red with monk in black habit, white face, hands and feet, brown stick, yellow bible and halo, n. Schwyz—red with left-hand figure blue, right-hand green, white faces, gold halos. o. Schwyz—red with gold canton, p. Schwyz—plain red. In later times carried small white cross, but not in this period, q. Nidwald (part of Unterwalden)—red and white, r. Obwald (part of Unterwalden)—reef and white, s. Luzern, also used at Marignano. Styles and details of all these Swiss flags seem to have varied a great deal. They are sometimes shown as "t" with a shield imposed on the flag, t. Papal flag used by Swiss at Marignano

About the Author

George Gush was educated at Tonbridge School, Kent, and won an Open Scholarship in History to Christ Church, Oxford, and has pursued a teaching career ever since graduation.

Acknowledgements

Article contents originally © Copyright George Gush and Patrick Stephens, Ltd 1975, 1982 and reproduced here with permission.

|

|