Renaissance Armies: The English—Henry VIII to Elizabeth

An article by George Gush

Suit of armour made at Greenwich for Henry VIII and dated 1540, now in the Tower of London

|

The service of the English army of the 16th Century was varied, if on a relatively small scale: a couple of expeditions against France, continuous trouble and two major conflicts with Scotland, lengthy wars in Ireland, aid to both sides in the Netherlands and to the Huguenots in France, plus preparations against various invasions which never came. In itself, the army is of particular interest, firstly in weaponry, with the insular retention of bill, cavalry lance, and, above all, longbow, long after their abandonment elsewhere; secondly in forced reliance on a national militia system throughout what was generally the age of the mercenary. The service of the English army of the 16th Century was varied, if on a relatively small scale: a couple of expeditions against France, continuous trouble and two major conflicts with Scotland, lengthy wars in Ireland, aid to both sides in the Netherlands and to the Huguenots in France, plus preparations against various invasions which never came. In itself, the army is of particular interest, firstly in weaponry, with the insular retention of bill, cavalry lance, and, above all, longbow, long after their abandonment elsewhere; secondly in forced reliance on a national militia system throughout what was generally the age of the mercenary.

Italian armour of 1550, typical of that worn by Enlglish demi-lances (Tower of London)

|

Englishmen had been compelled to keep arms according to their wealth (and in some cases their wives' wardrobes—a silk petticoat let you in for the expense of light horseman's equipment!) since the Assize of Arms of 1181, and the 16th Century effectively saw the continuance of this system, though with modifications.

All eligible were compelled to muster for inspection at varying intervals (up to twice a year in times of danger), the system being generally administered on a county basis, and run by Commissioners of Musters (replaced, from the reign of Mary, by the new Lords-Lieutenants). The Clergy, and Lords and their retainers, had similar obligations, administered separately. By the end of the century the militia, in theory at least, totaled a million men.

At first the troops returned home after inspection, unless an invasion threat caused them to be kept mobilized—Henry VIII kept 120,000 men on foot for a whole summer. From 1573, however, "Trained Bands" appeared, picked men from the general muster retained for drill, costs being paid by the city or county concerned. This reform was perhaps connected with the increasing use of firearms and pikes, both requiring considerable training (the bow, of course, required even more training, but this had normally been acquired by its exponents during their own time).

For service abroad, which was on a considerable scale in the last quarter of the 16th Century, troops had, of course, to be paid, but were often raised, complete with arms and armour, from the county militia or the Trained Bands (it was commonly those whose absence would be most welcome who were sent on foreign service!)

In the 17th Century the Militia system fell into decline, but by the Civil War was still the only basis for military forces in England—hence the efforts of both sides to gain control of it, and the important role played in the war by the Trained Bands of London.

Infantry Weapons and Organization

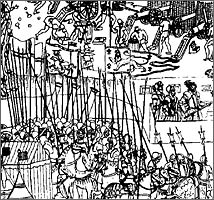

Artillery, billmen, longbowmen, and arquebusiers, with light cavalry, of Henry VIII's army (National Army Museum)

|

Henry VIII with his artillery and heavy cavalry (National Army Museum)

|

In the early 16th Century, nearly all were the traditional billmen and longbowmen, both usually equipped with a jack (a waist or knee length coat "quilted and covered with leather, fustian or canvas, over thicke plates of iron that are sowed in the same"), and with a simple rounded helmet of "skull" or sallet type. Even by the 1550s this was still largely true, corselets and morions being rare, and multi-layered canvas jackets or even mail shirts being still favored.

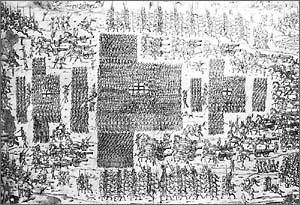

"Henry VIII's Army"—a 15th Century drawing showing the army drawn up in three "Battles" and including billmen, bowmen, arquebusiers, artillery, and lancers. (British Museum)

|

Henry VIII, the only military-minded English monarch of the period, began reform. As well as instituting home production of artillery and armour, he imported weapons in quantity (many are still at the Tower) and encouraged the adoption of artillery, the pike, and hand firearms. However, among 28,000 English foot taken to France in 1544, there were less than 2,000 arquebusiers, and billmen outnumbered pikemen three or four to one. Henry had to hire Spanish and Italian arquebusiers, and German pikemen.

The older weapons were gradually supplanted by the new, and in 1558 English companies in Ireland had about 50 each of longbowmen and arquebusiers. A Leicestershire company of 1584 shows a later stage in the transition, having 80 pikemen and 80 men with firearms, as against 40 billmen and 40 archers. Though Sir John Smith wrote approvingly of this organization in the 1590s, and recommended the formation illustrated, he was a longbow enthusiast, and it seems likely that the 1580s saw both the appearance of the musket and the disappearance of the bow from first line English service. The London Trained Bands dropped the bow in Armada year, and in 1595 it was ruled unacceptable for Trained Bands "shot" generally.

However, in the mid-1580s the general muster of the so-called "maritime" counties still included 32 percent archers, as against 40 percent with firearms and 28 percent corselets, or pikemen. Such counties as Wiltshire, Derby, Oxford and Bucks were the main suppliers of archers.

English infantry companies varied from 100 to 400 in strength, Sir Roger Williams apparently considering 150 to be standard in the 1590s. Some further examples are: 1558—150 armoured pikemen, 150 unarmoured pikemen, 100 arquebusiers; 1596—50 pikemen, 12 musketeers, 36 caliver men; 1599—30 pikemen, ten short weapons, 30 muskets, 30 calivers; 1600—20 pikes, ten halberds, six sword and buckler, 12 muskets with rests, 12 bastard (light) muskets, 40 calivers.

The word "Regiment" was used in Henry VIII's time to describe one of the three medieval-type battles into which armies were still divided (in 1544, 13,000 to 16,000 strong). Each of these would mass its pikemen and billmen together in from one to three large blocks, with wings of archers and other shot operating on their flanks. "Regiment" still had a very vague meaning in the mid-16th Century—all the troops operating in the Netherlands, 6,000 or more, forming one "regiment"—but by the later part of Elizabeth's reign, regiments were fairly definite organizations, commanded by a colonel. They could be of ten companies, as later, but in Ireland were often of five.

English drummer, fifer, arquesbusiers and halberdiers on

left, with Border Horse on right (British Library)

|

Enlish demi-lances, pikemen, and arquesbusiers of the 1580s

(British Library)

|

Cavalry

"Men-at-Arms", with heavy lance, full armour, and often barded horse, were still used in the first half of the century, but were few in number, though of high quality. In 1544, Henry VIII had 75 "Gentlemen Pensioners" or Household cavalry, and 121 Men-at-Arms. Individual noblemen would also serve in full plate. The appearance of such troops would be much the same in any army, though Englishmen might wear rounded Greenwich armour.

English man-at-arms of Henry VIII's period. Possibly Henry himself, or a Gentleman Pensioner (British Museum Manuscript Department)

|

Henry VIII's horse armour (Tower of London)

|

Much more numerous were the "demilances", with corselet only, or three-quarter armour, open burgonet, and unbarded horse. These men carried a lighter lance, and later pistols, and formed the main English heavy cavalry up to the end of the century.

According to Sir Roger Williams, in the late 16th Century, demilances formed a fifth of the English cavalry, the rest being light horse, but the proportions in the militia were nearer 1:3. The characteristic English light cavalry were those variously referred to as "Javelins", "Prickers", "Northern spears" or "Border Horse". They also were armed with lance and one pistol, sometimes carrying a round or oval shield as well, and wore an open helmet, mail shirt or jack (corselet for the wealthier individuals), leather breeches, and boots. Such cavalry were supplied by several English counties, but the best came from the raiders of the Scottish border, who were reputed to spear salmon from the saddle!

Nearly all English light horse were of this type, though by 1586 the Government were also trying to raise "petronels"—unarmoured cavalry with firearms.

Cavalry were always in short supply in English armies; Henry VIII supplemented them with Burgundians, and Germans with boar spear and pistols. In Ireland in the later 16th Century, cavalry usually formed about one-eighth of an English army. In Henry's time they were organized in bands, cornets, or squadrons of 100 men, later of about 50.

a. English officer of the 1580s carrying a partisan and wearing a sash, usually red in color, b. and c. Two views of an English mounted bugler of the same period. Note ruff-type collar, lace on front of jacket, and dagger carried on belt, d. A man of the London Trained Bands of Henry VlIl's period in white jacket with red St. George's cross on front and rear, e. Elizabethan Yeoman of the Guard. Jacket red with black stripes and gold patterning on breast. Rose is red-white-green. Cap black with grey feather and brow band. Ruff white. Breeches yellowish, slashed pink.

Dress

The general lines are indicated by the illustrations, and followed the lines of civilian dress of the period. Even the standing force, the small Sovereign's Bodyguard of the Yeoman of the Guard (who served both on foot with bow and halberd, and mounted with javelin) seem to have confined uniformity to jackets and caps. When raised by Henry VII, the jacket was white and green, with a rose on the chest; under Henry VIII and thereafter they wore red jackets, guarded in black, with rose and crown in gold, and red or black cap with white plumes, but breeches and hose could be of various colors. As gentlemen, the Pensioners probably scorned uniformity, but the illustrations may give some idea of their dress. When they became Gentlemen at Arms under James I, they wore red and yellow plumes.

English jacks of 1580 (Tower of London)

|

Militia contingents, which could be of company size or even larger, were supplied with uniform clothing, and some examples of this are listed: 1540—London Trained Bands: white jackets, city arms front and back, some with buff jerkins; 1553—Canterbury: yellow; 1556- Reading: (billmen) blue coats with red crosses; 1550s—Surrey: (demilances) red cassock with double white guard (border); 1558—London: white coats, slashed green, with red crosses; 1560s—Lancashire: (archers) blue cassock, double white guard, red cap, buckskin jerkin; 1560s—Derby: light blue; Stafford: red; 1576—Lancashire: white cassocks with one red and one green lace; 1577—Lancashire: pale blue coat, double yellow or red guard, white doublet, pale blue breeches with red or yellow stripe down seam, white stockings; 1585—London: red; 1585—Essex: (pikemen) blue mandelion (tabard-like garment worn over armour); 1587—Hertfordshire: (trained bands) red coats; 1588—Huntingdon: (the foot) "popinjay" (parrot) green, trimmed with the colors of the captain of the company; (Sir Henry Cromwell's Company of Horse) straw color, trimmed with his colors; 1590—Canterbury: red; 1596—London; red; 1599—Essex: russet coat and hose.

Contingents raised by noblemen might be clad in family or other colors (for example the Earl of Surrey brought 500 men in white and green to Flodden) and it seems that larger groups were sometimes uniformed—at the siege of Boulogne, Henry VIII's Main Battle and Rear Guard were dressed in red with yellow trim, the other forces in blue with red trim—and in 1558, 8,000 English sent to aid Spain in the Netherlands all wore blue.

In the early 16th Century, white was a favorite color for English troops (the Tudor colors were green and white); in the later part of the century red became most widely used. Blue, however, was also widely worn, and, for Irish service, cassocks (loose long or short coats, sometimes hooded or sleeveless, and worn over equipment) were usually to be of russet, green, or "sad" colors. Cavalry in Elizabeth's reign seem to have favored red, tawny or orange colors; Border horse usually wore white, and could wear "blue bonnets" like the Scots. English archers, too, often wore "Scots caps" in red or blue, over their helmets, and cavalry helmets were likewise sometimes covered with red or parti-colored caps.

The sign of the English soldier, worn on breast and back in the first half of the 16th Century, and found on shields and pennons later, was the red cross of St. George. Toward the end of the century sashes, worn about the waist or over the right shoulder by officers, and some pikemen and cavalry, became the usual national distinction. Red, or red and white, seems to have been worn by the English.

Officers were distinguished from their men, just as in other armies of this period, by armament (sword and buckler, half-pike, or partisan being favorite officers' weapons), and by rich clothing with silk and lace, gold or silver trim, decorated armour, and jewelry.

Flags

A number of English flags are shown. The St. George's cross on a white ground was evidently most common, sometimes combined with Tudor green-and-white, or the Tudor rose, but striped flags are often shown in paintings from Elizabeth's reign, possibly influenced by the Dutch.

Noblemen's units would be likely to display family crests or badges in case of cavalry, as with one guidon shown. At the battle of the Yellow Ford in Ireland, Percy's Regiment had a standard with silver crescents (a badge of the Percys) which could indicate something like the later Civil War system for company flags.

a. Plain white infantry flag with red St George's cross. Over six feet square, b. Infantry flag carried in Ireland in 1590s. St. George's cross red and white, other colors unknown, c. Infantry standard carried by Leicester's troops in the Netherlands, 1586. d. St. George's cross combined with Tudor white and green, e. Infantry standard in Ireland, 1593—white with red cross, f. Another flag carried in the Netherlands, colors unknown, g., h. and i. Three variants on the plain St. George's cross carried by infantry. j. Alternative shape for infantry standards. k., l., m., and n. Cavalry guidons, o. and p. Infantry flags of the 1580s. 'o' could be blue and white, red and white or black and white, 'p' is black and white. Contemporary pictures show such flags carried by units alongside St. George's crosses, as if the latter might be Colonel's company (regimental) standards, 'o' and 'p' ordinary company flags. Could the number of stripes indicate the company?

About the Author

George Gush was educated at Tonbridge School, Kent, and won an Open Scholarship in History to Christ Church, Oxford, and has pursued a teaching career ever since graduation.

Acknowledgements

Article contents originally © Copyright George Gush and Patrick Stephens, Ltd 1975, 1982 and reproduced here with permission.

|

|