| Author |

Message |

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Sat 06 Aug, 2022 8:42 am Post subject: Posted: Sat 06 Aug, 2022 8:42 am Post subject: |

|

|

Well we know from records of formal and informal duels that there were both overt, written, clear prohibitions against certain types of behavior, and implicit, vague, unwritten, unofficial rules about fighting which could be of equal importance when it came down to a magistrate or the general public evaluating an incident. In the German speaking areas for example thrusting with a blade was considered more serious than cutting which was considered more serious than striking with the flat, attacking people when they were down on the ground or when their back was turned was considered at least somewhat transgressive though there weren't any formal laws against it.

I previously pointed out that putting poison on a blade or other weapon would imply intent to kill, which certainly in some kind of personal or informal dispute would be seen as legally dubious. You might get away with it but you'd better have a really good reason.

Again, yes we could be looking at an informal or unstated prohibition, or a formal and legal one we haven't found yet. But I don't think we should dismiss the notion that it's just a poor grasp of the tactical realities (and glossing over, filtering or otherwise ignoring evidence) by modern scholars.

My analogies are never convincing here apparently but I'll give you another one. Throughout the 19th, 20th, and early 21st century most documentaries, historical overviews and many professional historians (including military historians) would tell you that early firearms such as those used in the 14th and 15th Centuries were very ineffective and (so the trope goes) were mainly useful for the "smoke and noise" they created, which may have scared horses and so on. Some people will still make this claim today.

I now know this to be incorrect, and many military historians today are much more cognizant of major events like the Hussite Wars where this trope is clearly baseless. But it was a very stubborn trope for a very long time. And this isn't exactly a fringe thing. By the third quarter of the 14th Century firearms were in wide use in most sieges all over Latin Europe and toward the end of the first quarter of the 15th Century firearms were an important component of field armies. In the 1430s they are showing up in the inventories of hundreds of expeditions and even small raids.

If they missed that, what else did they miss?

Anyway, we are engaging in speculation here and just exchanging opinions. What really matters is data.

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Sat 06 Aug, 2022 8:44 am Post subject: Posted: Sat 06 Aug, 2022 8:44 am Post subject: |

|

|

I would also add that for example by 1400, we are talking about dozens of major and hundreds of minor polities throughout Latin Europe, scores of different languages and dialects and so on. You might have an informal prohibition in some areas, but all of them seems unlikely.

That again though, is just my opinion.

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Mark Millman

|

Posted: Sat 06 Aug, 2022 3:16 pm Post subject: Posted: Sat 06 Aug, 2022 3:16 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Dear Jean,

Like your analogies, my attempts to be unambiguously clear seem never to succeed, but do please note that I wrote,

| Quote: | | . . . If research cannot discover clear evidence of military use of poison on weapons in medieval Latin Europe it seems necessary to explain why . . . [emphasis added] |

To be as clear as I can, I agree: More research--and very possibly reinterpretation of the currently known sources--needs to be done on whether poisoned weapons were used in military contexts in medieval Latin Europe, and on the reasons for use or non-use regardless of whether carefully examined evidence confirms or refutes such use, recognizing that the answers may vary over time and across groups within the broad span of "medieval Latin Europe".

Best,

Mark

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan S.

|

Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 3:22 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 3:22 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: |

Anyway, we are engaging in speculation here and just exchanging opinions. What really matters is data. |

I think that we have established some good starting points for data.

1. A list of arrow poisons that were used. It becomes a lot easier to find textual data when you know the right terms.

2. Several Classical texts that would have been available to educated Europeans that mention arrow poisons.

3. Some information about how Chinese used poisoned weapons.

4. Strong evidence for hunting use.

5. Evidence that suggests that the Greeks had used poison arrows, but had abandoned it.

6. Evidence of use in Grenada.

I think that Europeans were most likely to use aconitum or hellebore. Hellebore is a weaker poison, but then the plant is safer to handle. There is also textual evidence of both varieties being used for hunting. These plants are probably more available than snake venom. I know that it is possible to import it, and except for Ireland, native poisonous snakes exist in Europe. However, the evidence for either importation or use of native snake venom is, at least, unknown to members of this forum.

An interesting experiment would be to test arrows, and if you will, daggers with some substance that could serve as a poison analogue. Maybe food coloring. It wouldn´t be perfect. First step would be to weigh the arrow, and then apply the fluid and weigh again. Then one would shoot in a target covered in cloth, and then try to determine how much of the poison came off in the cloth and how much was actually delivered.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 6:58 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 08 Aug, 2022 6:58 am Post subject: |

|

|

That's not a bad list, but I have a couple of questions there and I think there are some ommisions.

Where is the evidence precisely that the Greeks (or Romans) abandoned the use of poisons? To the contrary it seems to continue. I personally don't know of evidence of it's use in battle, but when I started this thread I wasn't aware of the use of poison on weapons (such as arrow poisons) anywhere in Europe. In fact if you had asked me that day if I thought poison was used with weapons in Europe at any point, I would have said "probably not."

But I kept an open mind. Now I know a lot better and it hasn't exactly been due to a huge amount of research. Absence of evidence isn't evidence of absence.

I would add to your list:

- We know of the use of arrow poisons in China and Southeast Asia in a military context right into the 20th Century, with both bows and crossbows. Including light crossbows like the Zhūgě nǔ and the light weapons used by "Montagnard" Highlanders in Vietnam as late as the 1950s and 60s.

- The Greeks noted the use of arrow poisons in war by Scythians, Gauls, Dacians, Parthians, Persians and many others. Many of the poisons described have later been identified by modern toxicologists.

- A wide variety of poisonous plants were written about by Greek and Roman authors as suitable for use with weapons, including extracts of belladona, aconite (wolf's bane'), hemlock, monkshood, yew berries, rhododendron, and several different species of hellebore, of which black hellebore (Helleborus Niger) which is found around Northern Italy and the Alps, is the most potent.

- There is considerable etymological evidence of the use of poisons with weapons, from the Greek term for arrows and bows and poisons (τόξο / toxon) to the term 'spear drug' and the late medieval or Early Modern use of "crossbowman's herb" for Hellebore.

- Snake venom poisons were also discussed by Pliny and others, down to fine details of both production of the poison and antidotes.

- Highly venomous snakes like Egyptian cobras were routinely found within territories controlled by Greek, Roman, and later Medieval polities.

- Some snake venoms last a long time and do not rapidly break down.

- Poisonous minerals and metals, such as arsenic ores like orpiment and realgar, were widely available in Europe going back to Antiquity (both were used as pigments through the medieval period in Italy, Flanders and Germany). Modern toxicological manuals mention the use of orpiment on arrows in China.

- Ingested poisons were in wide use in Greek and Rome in Antiquity and their use was also well documented in the late medieval and early modern period (I can provide examples of this if needed).

- The term "crossbowman's herb" for hellebore seems to have remained current in Spain and Portugal (but not necessarily just Spain and Portugal) into the 21st Century. Some hunting treatises apparently claim that Hellebore based poisons could kill game animals 'within ten paces'.

- References to the use of hellebore as an arrow poison by 'crossbowmen', and not just specifically hunters, especially in Spain and Portugal (so far).

As for coating arrows, there is a technical issue here. The reference to it's use in battle by the Moors in 1483 said "1483, Arab archers wrapped aconite-soaked cotton around their arrowheads.". Arrows are typically very light, arrows used by Moors and Arabs were often in the 30-40 gram range. So adding some cotton could conceivably have a negative effect on ballistics and range. This may not have been as much of an issue for defenders shooting from high walls or towers, as the height advantage would to some extent compensate for the extra weight of the projectiles, but it's still an issue. Another related issue is, depending on the type of poison, did you need to add something like cotton to carry the substance or could it be applied directly to the metal of the arrow, spear, or quarrel head and remain long enough to deliver the payload.

We do know of a similar problem faced in the medieval period with the occasional need for fire arrows, mainly in sieges*. The solution in Latinized Europe was mainly through the use of powerful crossbows, which often typically provided excess energy capable of pushing heavier projectiles.

These show up in period literature, such as this image from a 15th Century Feuerwerkbüch...

..and we also have many surviving examples of these special projectiles.

We even have treatises which get into detail on how to make the arrows and the special compounds. These projectiles are probably carrying more weight than what you would need to deliver poison, although the dose needed and how easily it could be applied to a projectile point (would you need something like cotton etc.) would depend greatly on the specific type of poison of course.

I suspect the ability of late medieval and early-modern crossbows to shoot heavier projectiles (and the ability to place a bolt in readiness without any physical effort, making them a little safer to use conceivably) may be related to why Hellebore is called specifically "crossbowman's herb" rather than "archers herb". But that is just speculation.

* I'd like to remind Hollywood though that these were not necessarily used in open battle, or to attack people. They were generally used to set buildings and other structures on fire.

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan S.

|

Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 5:30 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 5:30 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: |

Where is the evidence precisely that the Greeks (or Romans) abandoned the use of poisons? To the contrary it seems to continue. I personally don't know of evidence of it's use in battle, but when I started this thread I wasn't aware of the use of poison on weapons (such as arrow poisons) anywhere in Europe. In fact if you had asked me that day if I thought poison was used with weapons in Europe at any point, I would have said "probably not."

But I kept an open mind. Now I know a lot better and it hasn't exactly been due to a huge amount of research. Absence of evidence isn't evidence of absence.

|

In Mayor´s book she writes:

"The great Greek physician of the first century AD, Dioscorides, was the first to remark on the derivation of the word “toxic” from “arrow.” But Dioscorides insisted that only barbarian foreigners—never the Greeks themselves—resorted to poisoned weapons. His assumption was widely accepted in antiquity and still holds sway today, as evident in a recent declaration about poison arrows by Guido Majno, the medical historian whose specialty is war wounds in the ancient world: “This kind of treachery never occurs in the tales about Troy.”"

https://erenow.net/ancient/greek-fire-poison-arrows-scorpion-bombs/4.php

So, Mayor sees herself arguing against the majority opinion when she says that the Greeks used poison arrows.

As far as the absence of evidence, as a truism that is true, but my position is that we don’t know that the Greeks and Romans used poison arrows in combat, your position is that we do. Or have I misunderstood? The Greeks and Romans were certainly capable of using poison arrows in warfare. The technology is probably from the stone age. I also think that sometimes the absence of evidence can mean more or less, depending on how much evidence there is and if a specific type is suspected. For example, we have a lot more evidence about the American Civil War, so it is easier to come to a conclusion about which weapons were used.

To apply this principle to poison arrows, if Herodotus doesn´t mention poison arrows, that doesn´t mean much. He doesn´t mention arrows much or go into much details about Greek military equipment. On the other hand, if a manuscript on treating arrow wounds doesn´t mention poison, that might mean something.

Really, we don´t know if the Greeks and Romans used poison arrows in warfare up to the migration period. Mayor´s sources for Greek use of poison arrows are mythological and therefore Bronze Age.

Last edited by Ryan S. on Sat 13 Aug, 2022 8:16 pm; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 12:57 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 10 Aug, 2022 12:57 pm Post subject: |

|

|

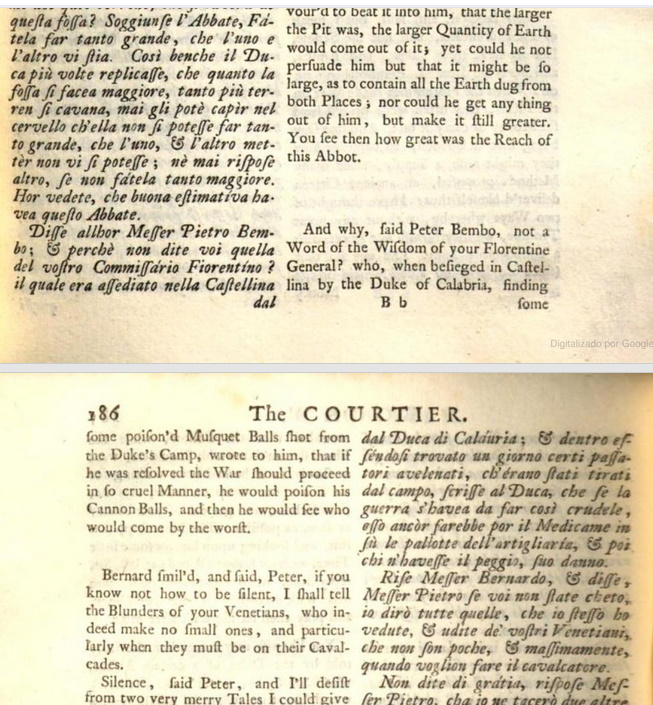

My buddy found a reference to poisoned musket balls from a famous source, in 1528. Source is Baldassare Castiglione "Il Cortegiano"

Ref: CASTIGLIONE, Baldassare (A. P Castiglione). Il Cortegiano or The Courtier, Londres: W. Bowyer, 1727, pp. 185-186 (link here)

The passage reads:

"And why, said Peter Bembo, not a word of wisdom of your Florentine general? who, when besieged in Castelina by the Duke of Calabria, finding some poisoned musquet balls shot from the Duke's camp, wrote to him, that if he was resolved the War should proceed in so cruel manner, he would poison his cannon balls, and he would see who would come by the worst."

Attachment: 228.16 KB Attachment: 228.16 KB

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan S.

|

Posted: Sat 13 Aug, 2022 9:05 pm Post subject: Posted: Sat 13 Aug, 2022 9:05 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: |

I would add to your list:

A- We know of the use of arrow poisons in China and Southeast Asia in a military context right into the 20th Century, with both bows and crossbows. Including light crossbows like the Zhūgě nǔ and the light weapons used by "Montagnard" Highlanders in Vietnam as late as the 1950s and 60s.

B- The Greeks noted the use of arrow poisons in war by Scythians, Gauls, Dacians, Parthians, Persians and many others. Many of the poisons described have later been identified by modern toxicologists.

C- A wide variety of poisonous plants were written about by Greek and Roman authors as suitable for use with weapons, including extracts of belladona, aconite (wolf's bane'), hemlock, monkshood, yew berries, rhododendron, and several different species of hellebore, of which black hellebore (Helleborus Niger) which is found around Northern Italy and the Alps, is the most potent.

D- There is considerable etymological evidence of the use of poisons with weapons, from the Greek term for arrows and bows and poisons (τόξο / toxon) to the term 'spear drug' and the late medieval or Early Modern use of "crossbowman's herb" for Hellebore.

E- Snake venom poisons were also discussed by Pliny and others, down to fine details of both production of the poison and antidotes.

F- Highly venomous snakes like Egyptian cobras were routinely found within territories controlled by Greek, Roman, and later Medieval polities.

G- Some snake venoms last a long time and do not rapidly break down.

H- Poisonous minerals and metals, such as arsenic ores like orpiment and realgar, were widely available in Europe going back to Antiquity (both were used as pigments through the medieval period in Italy, Flanders and Germany). Modern toxicological manuals mention the use of orpiment on arrows in China.

I- Ingested poisons were in wide use in Greek and Rome in Antiquity and their use was also well documented in the late medieval and early modern period (I can provide examples of this if needed).

J- The term "crossbowman's herb" for hellebore seems to have remained current in Spain and Portugal (but not necessarily just Spain and Portugal) into the 21st Century. Some hunting treatises apparently claim that Hellebore based poisons could kill game animals 'within ten paces'.

K- References to the use of hellebore as an arrow poison by 'crossbowmen', and not just specifically hunters, especially in Spain and Portugal (so far).

|

I am open to additions to the list, I will address your proposals one by one. To make it easier, I have given them letters.

A- That falls under Item 3 in my list.

B- That is correct, with I think the one addition that it be changed to the Greek and Romans as the source, because I think especially the information about the Gauls comes from Romans. (I admit I made a similar mistake earlier in this thread when I made a comment on the assumption that Pliny was Greek.

C- This falls under Item 1 of my list. Monkshood and Wolfsbane are the same. Also, Henbane (easy to confuse with Hellebore) seems to also have been important.

D- I am not sure, I would use the word considerable, or how useful that is. I don't think etymological evidence is that strong, either. Etymology is full of folk etymologies as well as theories that are argued by experts. It is certainly interesting that the Romans adopted the Greek word for arrow poison as a word for poison. I wouldn't call the name Crossman´s Herb, etymological evidence, it seems redundant.

E- I think you and I have a different idea of fine detail.

F- I am not sure if this tells us anything. Trade connection is more relevant, or evidence that cobra venom was used as arrow poison.

G- This is vague, so not really a data point. How long is long? Days? Months? Years? It seems that most people who store venom now, store it in very cold freezers. It also seems to have been thought that cooling venom makes it less potent, and some people think that still, but studies have disproven that. So it is possible that snake venom last a long time even in certain conditions. Snake venom is very complex and the different types vary. Similar snakes have similar venom, but sometimes key differences. We don´t even know what types of snake are supposed to have long-lasting venom.

H- Oh please don't provide examples again. It does seem that although the Romans and Greeks knew stuff was poisonous, it didn't mean they used it to kill people. Interesting is the Chinese use of orpiment as an arrow poison.

I- Again, I don’t know if this is relevant. Most of these poisons have already been covered by the list, so it isn't really new. In my opinion, it doesn't make sense to speculate what poisons they could have used, in addition to the many we know they used.

J and K- Does it explicitly say that it was for war? Before this thread started, I would have thought poisons were more suited for war as for hunting, but it seems that there is much more evidence that explicitly says that it is for hunting. Ambiguousness doesn't tell us much. I guess this is an expansion of number 2 as not only classical texts wrote about poison, but also medieval and early modern texts. Although it has seemed to narrow to just Crossbowman´s herb.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Sun 14 Aug, 2022 7:00 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 14 Aug, 2022 7:00 am Post subject: |

|

|

When I started this thread a couple of weeks ago, I was looking for data on an issue which someone had asked me about, but which I personally knew very little about - the historical use of poisoned weapons in Europe.

I got two kinds of responses, most people were posting various reasons why it wasn't possible, to kind of shut down or dismiss the discussion. Some were posting data, some started out doing the former and shifted to the latter.

The data was particularly welcome. But the dismissals were useful too, because they kind of created something like (an on my part, unintended) Socratic dialogue. So various objections were raised:

There was no poisoned weapons in Europe because it's not technically feasible to do it / it was too complicated.

... because they lacked the necessary raw materials (which lead to a subset of objections such as "Poisoned weapons relied on snake venom and there aren't many poisoned snakes in Europe" and "They couldn't import snake poison because it would go bad' etc.)

... because it was too expensive to import the necessary ingredients.

... because only people with weak bows used poisoned weapons.

... because poison doesn't work fast enough on the battlefield.

... because there is no evidence that they used it.

... because they had strong moral or cultural prohibitions against it.

... because snake venom would be rendered ineffective by combining it with feces or decaying flesh, per the method described by some Greek auctores.

Some of these arguments I dismissed outright. I knew that highly venomous snakes were found in and very near Europe, and that Classical polities in particular occupied lands where snakes like the Egyptian cobra are found in abundance. I knew that a huge variety of very expensive goods were imported down the Silk Road both during Antiquity and, at an accelerated rate since the time of Marco Polo. There is a great deal of data on this, a tiny bit of which I shared. I knew that in some battles in Antiquity, the Migration Era and medieval period, moral or ethical limitations on warfare (which certainly did exist) were thrown out the window. So a really strong, persistent cultural prohibition sufficient to always overrule pragmatic considerations seemed unlikely. I knew that cultures which did have powerful bows were also associated with the use of arrow poisons, so I felt that could be dismissed as well.

I also knew that snake venom was not the only type of poison that could be used on a weapon, and I knew some things being imported from China, India, Persia or the Pacific Rim were actually poisons. So I pointed this out.

So this was kind of helpful because it forced us to examine the objections, and from other research I had done rather deep dives into, I knew many of these objections weren't valid. That helped focus the most likely questions to ask, which got me closer to making some discoveries.

Some questions required further checking. By doing my own research and following up on some data posted here by various people, I learned that the Greek authors wrote extensively about poisons used as "arrow poisons" in the Classical era, and I learned that many plants were also used for "arrow poisons" and a wide variety of them from several different species were found in Europe. I shared what I found here. I learned that toxicologists seemed to know a lot of about arrow poisons which wasn't necessarily widely known by historians. (not an unusual situation).

We learned that Cobra venom, the chief ingredient which the Classical authors (many of them, not just Pliny, whatever his ethnicity which is completely irrelevant to me) noted was the chief ingredient in the poisons used by the Scythians in warfare, does not in fact break down rapidly. So even if they were importing it from China for some reason rather than just getting it from much closer Anatolian or North African sources, that would have been possible.

Then we found evidence of the ubiquity of certain plant based poisons for hunting, right through the medieval period and into the Early Modern, detailed formula / recipes for it's processing into an arrow poison, estimates as to a very high degree of lethality, and the persistence of the 'crossbowman's herb'.

Though the "dialogue" helped tease this data out, disagreeing with strangers on public fora isn't always a recipe for harmony and inevitably the process creates some friction. Some people are getting angry and still want to debate points which I think were very obviously already settled earlier in the thread. In some cases people involved in the discussion felt that their points were not being understood, or were misrepresented. I think this is inevitable again when people who don't know each other, and aren't necessarily reading all the nuance in a given post, are arguing online.

My goal was never to argue the point of poisoned weapons in Europe, since I went into it knowing very little. I have learned a lot for a thread like this, partly due to my own research, partly due to things posted here by several other people. For that, thanks. I may actually follow up on this further.

Following up on my friends discovery of the 16th Century source mentioned above, a little more googling has turned up several references in the 17th-19th Centuries of the use of poisons with firearms. For example, the British accused American Colonial militias of poisoning musket balls at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. A Scottish "Covenanter" confessed to poisoning a pistol ball which he intended to use for an act of assassination in 1680. This source claims that several Native American tribes adapted arrow poisons to their firearms using a variety of methods and substances, both for hunting and war. And so on.

Obviously there is a lot more to learn about this, in fact I sense that it is perhaps a fairly major avenue for further exploration. Without any doubt "hellebore" was a highly effective poison in long use for hunting through the medieval period and well into the Early Modern. I think it's likely that this goes all the way back to the Gauls though I haven't found evidence to support that yet. I also think it is unlikely that something well known to be so effective for hunting would never be used in war. It might be rare, there may have been some cultural rules against it, but precisely what those were and how strictly they were enforced (and by what mechanism) remains unknown to me at this time.

More digging into this will bear (poison) fruit, that is without any doubt. More arguing about subtle differences in semantics however, or going round and round over things which seem pretty obvious to me, seems to be pointless, especially as certain people have obviously gotten their feather's ruffled.

For those who I have annoyed by apparently misunderstanding parts of their posts (for example Mark Millman), I apologize. I stand by what I wrote, but I don't pretend to have superpowers when it comes to parsing fairly complex arguments being made in online forums.

Beyond that, I think I have the answer to my initial query, and anyone interested has an interesting avenue for further exploration. If I find some particularly salient data related to this subject I'll start another thread here to share it. At the moment I have some other priorities taking precedent and I think the signal to noise ratio on the discussion is falling for this thread.

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

Last edited by Jean Henri Chandler on Sun 14 Aug, 2022 7:53 am; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Sun 14 Aug, 2022 7:50 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 14 Aug, 2022 7:50 am Post subject: |

|

|

One last data point for now -

This article seems to mention crossbow-militia in 14th-15th Century Portugal (besterios do conto) being expected to practice putting poison (specifically hellebore) on their bolt-heads or quarrel heads as part of weekly militia training.

https://www.academia.edu/44113588/Crossbowmen_in_late_medieval_Portugal_and_Sweden_A_comparison

The authors source appears to be

BARROCA, Mário Jorge, 2003 – Da Reconquista a D. Dinis, in Manuel Themudo Barata & Nuno Severiano

Teixeira (Dir.). Nova História Militar de Portugal. Rio de Mouro: Círculo de Leitores, vol. I, p. 21-161.

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Mark Millman

|

Posted: Sun 14 Aug, 2022 8:58 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 14 Aug, 2022 8:58 am Post subject: |

|

|

Dear Jean,

| On Sunday 14 August 2022, you wrote: | | For those who I have annoyed by apparently misunderstanding parts of their posts (for example Mark Millman), I apologize. I stand by what I wrote, but I don't pretend to have superpowers when it comes to parsing fairly complex arguments being made in online forums. |

Thank you for your kind, although unnecessary, apology, which I am pleased to accept. In turn, if I have said or done anything that you found irritating or troublesome, I apologize; that was not my intention.

Best,

Mark

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan S.

|

Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 5:24 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 5:24 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: | When I started this thread a couple of weeks ago, I was looking for data on an issue which someone had asked me about, but which I personally knew very little about - the historical use of poisoned weapons in Europe.

I got two kinds of responses, most people were posting various reasons why it wasn't possible, to kind of shut down or dismiss the discussion. Some were posting data, some started out doing the former and shifted to the latter.

|

I don't think that anybody was trying to shut down the discussion. I know, that personally, I was trying to keep it going. I have been puzzled by some of your reactions, but now I see, you have misinterpreted mine and other motives from the beginning. You also seem to have misunderstood almost everything that people wrote here.

| Quote: | | There was no poisoned weapons in Europe because it's not technically feasible to do it / it was too complicated. |

I am not sure who was supposed to have said this. But, you yourself seemed to hold the opinion at one point that medieval Europe didn’t use poison weapons. I think, therefore, many people were trying to explain this.

| Quote: |

... because they lacked the necessary raw materials (which lead to a subset of objections such as "Poisoned weapons relied on snake venom and there aren't many poisoned snakes in Europe" and "They couldn't import snake poison because it would go bad' etc.)

... because it was too expensive to import the necessary ingredients. |

I don’t think that anyone suggested that snake poison was the only poison. It was proposed that the reasons that China used poison and the Europeans didn't, is that the Chinese had more powerful poison, and the example given was the Chinese Cobra. Your reaction to say that idea was absurd, I tried to reason with you that it was not absurd, and furthermore argue that there is no proof of Europeans importing snake venom. The idea that snake venom will go bad if not stored in cooled conditions is actually widespread among people who milk snakes. They may be wrong. The idea that snake venom might be cost-effective in China but not imported to Europe is a very reasonable thesis. I think the biggest problem with all this, is that I don´t think that there is any evidence that the Chinese used cobra venom, but I may have missed that part.

. | Quote: | .. because only people with weak bows used poisoned weapons.

|

Weak bows here, meaning also bows that shoot light arrows. Then yes. This appears to be the leading opinion in academia. Academia can be wrong, but this theory, in my opinion, is worth discussing.

| Quote: | | ... because poison doesn't work fast enough on the battlefield. |

My point was, that in order to be effective, the arrow or whatever weapon would have to carry a dose strong enough to work in a time to effect the battle. How well this works, is a big factor in the cost-benefit analysis. I thought this would be obvious.

| Quote: |

... because there is no evidence that they used it. |

You have repeatedly said that it is established that the Romans and Greeks used poison arrows. That is not the case.

| Quote: | ... because they had strong moral or cultural prohibitions against it.

|

You said that, I argued against that.

| Quote: |

... because snake venom would be rendered ineffective by combining it with feces or decaying flesh, per the method described by some Greek auctores. |

I questioned the reliably and accuracy of ancient sources, which you seemed to put a lot of faith in. My goal was to get you to at least understand why someone would doubt that they are 100% true. I will point out that Sean, referred to the use of skythikon as rumours. Of course, rumours are not necessarily false, but one shouldn't treat them as truth. You seemed, and please correct me if I am wrong, to have been basing your belief that Romans and Greeks used poison on this source, or sources (although, it is probable that one source is based on the other. If Greeks used poison (and find I, Mayor’s argument that they at one time did, convincing), they probably did not use skythikon, and the “recipe” is not sufficient to reproduce the poison. It is also possible that the “recipe” was partly or entirely made up. This in no way proves that the Latin Europeans, or who ever, didn’t use poison. It isn’t proof that the Skythians didn’t use poison. It isn’t proof of anything, and I didn’t mean it that way.

In general, you have treated sources as equal, listing poems and what are at best third hand accounts as equal to first-hand accounts. How much faith to put into sources and how to interpret them is subjective. As well as a certain degree is estimating if someone else had thought something to be expensive. In light of this subjectivity, you could probably be more lenient towards people who have ideas that you find absurd or not worth considering.

| Quote: | | Though the "dialogue" helped tease this data out, disagreeing with strangers on public fora isn't always a recipe for harmony and inevitably the process creates some friction. Some people are getting angry and still want to debate points which I think were very obviously already settled earlier in the thread. In some cases people involved in the discussion felt that their points were not being understood, or were misrepresented. I think this is inevitable again when people who don't know each other, and aren't necessarily reading all the nuance in a given post, are arguing online. |

I find that harmony is easier when one assumes that strangers on the internet are collaborators and not your opponents. That, and they aren’t always disagreeing with you, and even if they disagree with you, in might be only in degree.

| Quote: | as certain people have obviously gotten their feather's ruffled.

|

I have the feeling that you are being indirect, so to clear things up. When you say certain people, do you mean yourself? or are you implying that you are not upset. Mark, the only person you named seems not to be upset or have been upset. I have already expressed frustration at the difficulty of communicating with you, but it is the lack of success that bothers me more than anything else. Miscommunication happens and is not something worth getting hung up on.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 5:59 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 5:59 am Post subject: |

|

|

Thanks Mark and no worries. Also please accept general apologies to others I annoyed.

But at this point, with the latest data point, I think it's pretty clear now that 'arrow poisons' were in fact used in warfare and not just hunting, at least in late medieval Portugal and almost certainly in the states which make up what is now Spain as well. So the boundaries of this whole issue are now realigned once again.

Maybe their involvement in the Reconquista had something to do with their open use of arrow poisons. Or maybe it was widespread all over Europe and just not something that most 19th-20th Century historians focused on for various reasons. If it was used in Spain and Portugal, I doubt it was 100% limited to Spain and Portugal. For one thing Castilian, Almogavar, Aragonese and Portuguese soldiers fought outside of the Iberian peninsula. For another, the Reconquista was only one of many bloody, ruthless multi-generational wars fought against Muslim polities. The Eastern frontiers of Latin Christendom were even more perilous. But we can't say for sure whether arrow poisons were or were not used without more data.

It's never a good idea to be too rigid in approaching historical matters. The world is always more complex than our theories. The data tells the story but we can only ever partly understand it, and one has to accept that our understanding will continuously change and mutate (so long as we are willing to allow our theories to fit the data rather than try to force it to be the other way around).

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

Last edited by Jean Henri Chandler on Mon 15 Aug, 2022 8:41 am; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 7:38 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 7:38 am Post subject: |

|

|

Ryan,

I don't think further discussion between the two of us can be of any benefit to either of us.

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

Last edited by Jean Henri Chandler on Thu 18 Aug, 2022 8:20 am; edited 2 times in total

|

|

|

|

Benjamin H. Abbott

|

Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 3:59 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 3:59 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: | One last data point for now -

This article seems to mention crossbow-militia in 14th-15th Century Portugal (besterios do conto) being expected to practice putting poison (specifically hellebore) on their bolt-heads or quarrel heads as part of weekly militia training.

https://www.academia.edu/44113588/Crossbowmen_in_late_medieval_Portugal_and_Sweden_A_comparison

The authors source appears to be

BARROCA, Mário Jorge, 2003 – Da Reconquista a D. Dinis, in Manuel Themudo Barata & Nuno Severiano

Teixeira (Dir.). Nova História Militar de Portugal. Rio de Mouro: Círculo de Leitores, vol. I, p. 21-161. |

Thank you for this. I can't immediately figure out how to get a look at the source. Assuming Leandro Ferreira & Martin Neuding Skoog describe it accurately, that does at least strongly suggest these besterios do conto used poison in war. We'll see if folks come across more evidence for the use of poisoned projectiles in medieval European warfare. I know I'll be keeping an eye out for it. If the available poisons were as potent as that 17th-century text claims, it seems like using poisoned projectile would grant a meaningful advantage. I've long been curious about why we don't have more evidence for poisoned weapons on historical battlefields, given the theoretical effectiveness.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 6:45 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Aug, 2022 6:45 pm Post subject: |

|

|

yeah there is still a lot of mystery in this. Just because they routinely trained to put poison on their quarrels doesn't mean they actually used it on a routine basis. We spent a lot of time learning to throw hand grenades in boot camp when I was in the military, but I don't know anyone who actually ever threw one in battle. It's just not the kind of thing you want to screw up if you ever do have to use it.

There certainly does seem to be at least some hesitation and often the feeling of negative connotations on the use of poison in medieval and early modern Europe. Maybe it's just for legal reasons, maybe cultural, maybe a complex combination of both in various different times and places.

But on the other hand there is considerable evidence for it, and it's not that hard to find... yet somehow the historical overviews and synopsis seem to have missed it. Like I said before, it wouldn't be the first time something like this happens. I think there is a lot more to learn.

When I find more time I'm going to figure out the search terms in several different languages and take a hard look at some German war manuals and herbal books, because it's a safe bet the latter at least will at least cover hellebore and many of these other plants, and the snakes too. I think there is a lot more to learn here.

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan S.

|

Posted: Sat 20 Aug, 2022 5:25 am Post subject: Posted: Sat 20 Aug, 2022 5:25 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: | Ryan,

I don't think further discussion between the two of us can be of any benefit to either of us. |

I am disappointed you feel that way, but there appears to be nothing I can do about it.

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan S.

|

Posted: Sat 20 Aug, 2022 6:13 am Post subject: Posted: Sat 20 Aug, 2022 6:13 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Benjamin H. Abbott wrote: |

Thank you for this. I can't immediately figure out how to get a look at the source. Assuming Leandro Ferreira & Martin Neuding Skoog describe it accurately, that does at least strongly suggest these besterios do conto used poison in war. We'll see if folks come across more evidence for the use of poisoned projectiles in medieval European warfare. I know I'll be keeping an eye out for it. If the available poisons were as potent as that 17th-century text claims, it seems like using poisoned projectile would grant a meaningful advantage. I've long been curious about why we don't have more evidence for poisoned weapons on historical battlefields, given the theoretical effectiveness. |

I think that effectiveness is a tricky thing. If poison arrows were a game changer in war, then everyone would use them. My guess it that the effectiveness of poison is tied to the effectiveness of the projectiles that carry them. If most of the arrows don't injury the enemy at all, then even the most powerful poisons are useless, or worse dangerous to both sides who risk stepping on the things.

Anyway, it does seem that there has been more research on the topic than previously thought. Lewis Lewin a famous German pharmacologist. He wrote a book called Die Pfeilgifte. He mentions some things already mentioned here, but adds a lot, and provides a lot of leads for further research. When I have the time I will post a summary of the European section here in English. Some teaser information; he says the poison arrows would an usual weapon in Spain and mentions German laws on poison weapons!

https://archive.org/details/diepfeilgiftenac00lewi

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan S.

|

Posted: Mon 22 Aug, 2022 1:48 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 22 Aug, 2022 1:48 am Post subject: |

|

|

Louis Lewin´s book is structured and divided into sections by continent. The section on Europe seems to be the shortest, probably because he had less to research, as in other regions where poison arrows were still in use. As I write the highlights, I will follow his structure and try to communicate his opinion as short and clear as possible.

1. Celts, Gauls, Franks, Merowinger, Vandals, Nordic Peoples

Lewin starts out this section by saying that the use of poison arrows dates to prehistoric times. The first mention of the Celts using arrows he credits to Aristoles, and tells the story we know already about the using a poison arrow to hunt and cutting out the meat around the wound. Lewin disagrees that the reason for cutting out the meat was to prevent it from rotting, and argues that the poison would be more concentrated in the area around the wound and more dangerous. Only snake venom is the only edible poison that Lewin knows (and he knows a lot about poison). He then points out that Pliny and Aulus Gellius repeat the same story, only adding that the poison is hellebore and changing the reason for cutting the meat out.

Moving on to the Germanic tribes, he notes the Franks used them in war and cites examples. According to Gregory of Tours(500s AD) during the reign of Maximus. A Roman commander named Quintus fought against Franks near Neuß in 388 and was attacked by poison arrows. The poison was said to be made from herbs and so strong that a scratch would kill.

The next incident involves the Merowinger Sigebert I of Austrasia, who was in a sort of civil war with his brother Chilperic I of Neustria. After Sigebert defeated his brother, Chilperics wife hired two servants to assassinate Sigebert with poisoned scramasaxes. Lewin comments that the poison didn't have time to work as Sigebert was stabbed on both sides, screamed and fell over dead. She tried the same trick again on Sigebert´s son, this time with special made knives and two clerics, but this time they were caught.

After that, Lewin mentions that in the Lex Bajuvariorum and the Salic law, shooting someone with poison arrows is explicitly listed as a crime and punished with a fine. In other laws of Germanic tribes there are laws against attempted and successful poisoning, but not explicitly against poisoned weapons. Some tribes however have no specific law against poisoning. In the 12. and 13. century there were laws not only against poisoning but also against possession and sale of poison. The punishment of was death.

According to a medical book from 1594, poison projectiles were used in 1552 as Charles V sieged Metz.

The Vandals used poisoned throwing spears in the 5th century.

2. Dacians, Dalmatians and Slavs

Paul of Aegina wrote that Dacians and Dalmatians used poison arrows with helenium and ninum. The poison is said to only work through open wounds and not orally.

In 1118 The Byzantine Emperor John cut himself with a poison arrow while hunting and later died from it. Lewin believed the poison to be snake venom.

There are a couple of stories of Slavs using poison arrows. First in the 6th and also in the 9th century from the Eastern Roman Emperors Maurikos and Leo VI respectively. Later, Henry the Lion and Frederick Barbossa both were attacked on their separate pilgrimages by Serbians using poison arrows. One knight and two pages from Henry’s entourage were hit. Only one page died. Lewin has a quote from the two survivors that says the Serbians used poison so that no one that was hit would survive.

3. Arrow poison in German Chivalric Epics

Lewin notices that poison arrows were often mentioned in some German Epics. He quotes an Epic, but the German is too old-fashioned for me to understand.

4. Saracens in Italy

Apparently the Hohenstaufen in Italy had Saracens in their employ who used poison arrows. The source in the contemporary Mathias Paris. There is also a story that Otto II died from a poison arrow, but a year after. Lewin expresses scepticism. Also, Petrus of Abano testifies to poisoned swords towards the end of the 13th century.

5. Arrow Poisons in the 14th to 16th century French, Spanish, Waldensians, Hussites.

According to Ruffi, the Landvogt of Marseille gave permission for people to hunt roebuck, deer and wild boar with poison arrows. The surgeon Ambroise Pare wrote about the contemporary use of poison arrows and throwing spears. However, he doesn’t seem to know much about the poison used (according to Lewin).

Next he quotes Braunschwieg, who was already mentioned in this thread. The German is hard for me to understand. Lewin notes that the method to poison arrows is unusual and not found elsewhere. The poisoned person has to lose his thumb.

Lewin says that the Hussites were said to have used poison weapons in desperation, but expresses the opinion that they may be innocent.

Moving onto the Spanish, who seem to have used poison arrows the longest, he talks about Johannes Crato von Kraftheim, who mentions in a letter that Emperor Ferdinand mentioned that Spanish hunters carried white hellebore in a horn for hunting deer with arrows or spears. Alonzo Martinez de Espinaz , who served Philip III also writes about Spanish hunters doing the same thing. Also, Moors used poison arrows in the time of Philip II.

Thuanus writes of Alfonus Portocarreus (1570) being wounded by a poison arrow shot by moors. He fought on, till the poison killed him. Before firearms, poison arrows were normal weapons. Thuanus writes where the herbs were gathered. Thuanus writes that the Waldensians used poison on their arrows, swords, spears and lead shot, in order to kill both men and animals. Genser, another historian, writes the same thing about the Lucerner. Thuanus also writes about residents of the Alpine valleys in Savoy and Switzerland. They are said to have used poison for arrows and knives relatively long. Apparently they used the poison knifes to slaughter birds so that they die faster, as well as to make the meat more tender.

There is more, but I will post about that later.

Last edited by Ryan S. on Tue 23 Aug, 2022 3:40 am; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

|

Sean Manning

|

Posted: Mon 22 Aug, 2022 7:52 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 22 Aug, 2022 7:52 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Ryan S. wrote: | | Louis Lewin´s book is structured and divided into sections by continent. The section on Europe seems to be the shortest, probably because he had less to research, as in other regions where poison arrows were still in use. As I write the highlights, I will follow his structure and try to communicate his opinion as short and clear as possible. |

Thanks for the summary! I think Thuanus is Jacques Auguste de Thou who died in 1617 and Gesnerus is Conrad Gessner who died in 1565. So they were antiquarians trying to discover past practices.

If anyone can find the source about the Waldesians poisoning their spears, I hope they post it!

www.bookandsword.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2024 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|