| Author |

Message |

Craig Peters

|

Posted: Sun 05 Mar, 2017 6:32 pm Post subject: "The Effectiveness of the Sword/Long Bow/Crossbow/Gun/P Posted: Sun 05 Mar, 2017 6:32 pm Post subject: "The Effectiveness of the Sword/Long Bow/Crossbow/Gun/P |

|

|

So often on myArmoury people post threads about the effectiveness of this and that weapon: wanting to know how powerful it was, how crucial its role in the battles or conflicts in which it was used, how much of an advantage it gave to the armies using it. This trend is not simply confined to history enthusiasts and amateur discussions; professional historians likewise weigh-in on the “tactical” strengths or benefits offered by a particular military technology and how these technologies were central in shaping the outcomes of human conflicts in the past.

However, Kelly DeVries has written an article entitled “Catapults are not Atomic Bombs: Towards a Redefinition of Effectiveness in Premodern Military Technology” that is critical of the way many enthusiasts and historians over-emphasize the “effectiveness” of a particular weapon or technology. Although his article was written in 1997, the points it raises are still of relevance to historiography and amateurs of history, today. The opening section of his essay is worth transcribing to see the criticisms he raises regarding efficacy.

“Early in 1996 we all read about the sad death of Sergeant First Class Donald Allen Dugan, the first American soldier killed in the NATO peacekeeping mission in Bosnia. The weapon which killed him, at least according to the initial news reports, was a landmine. The number of these unexploded mines is extraordinary; some six million are buried below the soil of Bosnia, with only 20 percent known or 'remembered' by the warring factions. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of soldiers and civilians may die from these landmines, as they did from the numerous mines laid in Vietnam and Korea. Yet military historians and historians of technology would never refer to this weapon as 'decisive', 'invincible', or 'revolutionary'. Indeed, very few modern military technologies are referred to by these terms. Despite playing significant roles in the outcome of the First World War, neither the machine gun, the tank, noxious gas, the airplane or the submarine is determined to have 'won' or 'lost' that war. And if last year's discussion of the use of the atomic bomb to end the Second World War is any guide, the 'decisive' definition even of that weapon is in dispute.

“Such seems not to be the case in the scholarly discussions of premodern military technology. There continues, as can be seen in recent publications by Robert Drews, George Raudzens, Clifford J. Rogers, David Eltis and Geoffrey Parker, among others, to be an almost constant willingness to describe premodern military technology in those deterministic terms which modern military technology prohibits. The question of 'effectiveness' is at issue here. To these authors and many others who have favourably accepted their work, many premodern weapons are effective because they did more than kill and kill many. Some premodern weapons were effective because they were invincible against other weapons. Some were decisive on the battlefield and at sieges. Some were effective because they turned the tables on older, more traditional military practices: they reversed military social classes—medieval peasants being able to defeat knights, etc.—or they created economic and political catastrophe. Still others were revolutionary in that they determined the course of later world history.

“All these recent efforts to define the 'effectiveness' of premodern military technology in deterministic terms have done military history and the history of technology a disservice. Not only has this inhibited progress in understanding premodern military history in general, and premodern military technology in particular, but it has also too often and too easily removed the individual soldiers and their leaders from the military historical equation, replacing them with a technological, deterministic explanation.”

DeVries goes on to look at a few case studies: “The Catastrophe” of 1200 BC, the English Longbow, and the Military Revolution of 1560-1660. You can read the rest of the article here:

https://www.academia.edu/22787729/Catapults_are_not_Atomic_Bombs_Towards_a_Redefinition_of_Effectiveness_in_Premodern_Military_Technology

|

|

|

|

|

Pieter B.

|

Posted: Mon 06 Mar, 2017 5:09 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 06 Mar, 2017 5:09 am Post subject: |

|

|

Hows the military revolution debate going anyways? I still feel the term is essentially a misnomer for what is a long drawn out military evolution.

Thanks for posting the article.

|

|

|

|

|

Lafayette C Curtis

|

Posted: Tue 18 Apr, 2017 11:35 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 18 Apr, 2017 11:35 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

The academic world is already beginning to accept the "evolution rather than revolution" (or, perhaps more accurately, "creeping revolution" or "revolution through evolution") paradigm contra Geoffrey Parker's original sudden revolution (and Parker himself seems to have considerably modified his views), but of course the popular discourse is still stuck on processing the revolution thing.

|

|

|

|

|

Clifford Rogers

|

|

|

|

|

Henry O.

|

Posted: Tue 02 May, 2017 7:18 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 02 May, 2017 7:18 am Post subject: |

|

|

Accounts from the early modern period tend to call musket fire pretty deadly as well, even if in reality only one bullet out of every couple hundred found its mark. And muskets seem to have been considered more effective than longbows were, even when armor was falling out of use.

I think the issue with technological determinism in the pre-industrial era is that there aren't many factors to limit the adoption of per-modern technologies. Today not everyone can build a stealth fighter in their backyard because it requires a whole lot of background knowledge from multiple fields of study and a ton of pre-existing infrastructure. But in the middle ages it wouldn't exactly take a phd to make a bow but slightly longer/thicker, and we know the continent didn't have any shortage of yew. If the success of the longbow really was due to technology then why wasn't it immediately copied everywhere, and what prevented it from being invented earlier? At best it seems like more of a cultural phenomenon that left the english with an unusually high number of strong archers during the 1300s and 1400s.

|

|

|

|

|

Timo Nieminen

|

Posted: Tue 02 May, 2017 2:20 pm Post subject: Posted: Tue 02 May, 2017 2:20 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Henry O. wrote: | | But in the middle ages it wouldn't exactly take a phd to make a bow but slightly longer/thicker, and we know the continent didn't have any shortage of yew. If the success of the longbow really was due to technology then why wasn't it immediately copied everywhere, and what prevented it from being invented earlier? At best it seems like more of a cultural phenomenon that left the english with an unusually high number of strong archers during the 1300s and 1400s. |

As far as the technology goes, self bows of similar draw weights were independently invented many times, in New Guinea, Africa, and Europe. If you add bows of different construction and similar draw weights, there are even more.

The cultural/social part matters. It doesn't help you in battle if you have 10,000 150lb longbows and only 10 archers who can use them. To usefully adopt the high-draw-weight longbow in large numbers, you need large numbers of archers capable of using them, and that can mean changing the cultural/social system. That can be much harder to do than just buying/making the bows.

Given sufficient desire, the cultural/social system can be changed. It's a barrier to adoption of the weapon system, but not an insurmountable one.

"In addition to being efficient, all pole arms were quite nice to look at." - Cherney Berg, A hideous history of weapons, Collier 1963.

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Wed 03 May, 2017 9:26 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 03 May, 2017 9:26 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Henry O. wrote: | | why wasn't it immediately copied everywhere, and what prevented it from being invented earlier? At best it seems like more of a cultural phenomenon that left the english with an unusually high number of strong archers during the 1300s and 1400s. |

I don't think it had anything to do with that. Extremely heavy bows had been "invented" and were used for centuries before the 1300s. The Ballinderry bow was 10thC and was around 150lb. Otzi's bow was estimated to be around 160lb.

The only thing that changed was the application of masses of archers capable of shooting them, not the bow itself.

As a side note of sorts, we also need to move away from thinking yew was the critical factor. It's not a better bow wood than anything else, and doesn't allow you to make heavier bows. It's just way, way faster to make a bow from yew which is why it was used to supply thousands of bows during warfare.

|

|

|

|

M. Eversberg II

|

Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 9:32 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 9:32 am Post subject: |

|

|

[quote="Will S"] | Henry O. wrote: | | It's not a better bow wood than anything else, and doesn't allow you to make heavier bows. It's just way, way faster to make a bow from yew which is why it was used to supply thousands of bows during warfare. |

Why is this the case?

M.

This space for rent or lease.

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 10:43 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 10:43 am Post subject: |

|

|

Because not only can you tiller a yew bow badly, quickly and clumsily and still make them heavy enough to do the job without them failing, but you can also virtually ignore huge knots, pin knots, rot, spalting, grain violations, twist, sideways bend and just about any other natural issue wood can have.

If you're working an ash, hazel, holly, apple, plum, laburnum, elm or any other meane wood stave down to a bow and it has natural twist, that needs to be removed with heat. If you nick a growth ring on the back you need to go down an entire ring to ensure the back is flawless. If you encounter a knot it must be very carefully worked around etc etc. Once you've finished a meane wood bow it needs to have it's belly tempered using heat to prevent "chrysalling" which is the slow compressive failure of the belly fibres.

You could almost cut a bow shaped lump out of a yew tree with a chainsaw while half asleep and it would happily chuck a few dozen arrows out at an immense draw weight. It wouldn't last particularly long which is why for modern bows these issues need to be dealt with far more carefully, but if you're mass producing them in their thousands for a very short lifespan it just doesn't matter.

Also, you can use almost any cross section to make a military weight yew bow - while the Victorian D section wasn't ever really used, the oval, galleon, round and lozenge cross section all work well. In comparison each species of white wood requires a different cross section in order to function properly.

Alongside this, yew can be left completely unfinished with no wax, oil or resin coat to protect the timber and it will have no issue whatsoever. If you make a heavy white wood bow, it needs to be meticulously sealed from moisture as white woods are so hygroscopic that the bow will take lots of set and the performance will disappear after a few hours of shooting in humid conditions.

Essentially, yew becomes a bow with the most minimal effort if you're not worried about appearance or extended use.

|

|

|

|

Terry Thompson

Location: Suburbs of Wash D.C. Joined: 17 Sep 2010

Posts: 165

|

Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 2:38 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 2:38 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I will disagree with Will on a couple of points. Yew isn't much easier than most other woods to work into a bow. To the contrary, you still need to be very careful to work around knots, and not to penetrate multiple growth rings to prevent splintering. Simply planning or draw knifing through a knot (or layer of growth) in yew is an immanent break. It is actually why yew bows can tend to look very jagged or asymmetrically "wonky" when made well.

There are actually several hardwoods used for bows that do grow very strait grained and can be worked with minimal concern for penetrating multiple growth rings. Ash is one of them. But relatively speaking, English style bows were fast to manufacture compared to composite reflex/deflex bows used on the continent (as seen in hunting illustrations). And the lack of horn plates and/or sinew required in composites helped not only in speed of manufacture but also in material cost.

It's true that yew (where sap and heartwood are used) does tend to be less affected by "limb set" or "string-follow" than other self bows, it is attributed more to it's modulus of elasticity rather than any natural hydrophobic properties. Yew wood should still be treated with wax and/or oils to prevent moisture/saturation which can cause warping and swelling. I'm pretty sure it's even commented on in Ascham's Toxophilus.

(Actually just google searched and found the text "When you have brought your bow to such a point as I speak of, then you must have an herden or woollen cloth waxed, wherewith every day you must rub and chafe your bow, till it shine and glitter withal: which thing shall cause it both to be clean, well favoured, goodly of colour, and shall also bring, as it were, a crust over it, that is to say, shall make it every where on the outside so slippery and hard, that neither any wet or weather can enter to hurt it, nor yet any fret, or pinch, be able to bite upon it; but that you shall do it great wrong before you break it. This must be done oftentimes, but especially when you come from shooting." -Roger Ascham Toxophilus)

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 4:05 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 4:05 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I've got about 7 bows that I've made that would counter all of that in one go

I made a lovely 150lb Mary Rose replica from terrible quality yew as an experiment a year or so back - went through the growth rings and knots without thinking about them, just like you can see on the original Mary Rose bows.

I've also got numerous yew bows that are between 120 and 140lb with rot, spalting, sliced knots, violated growth rings and more, along with plenty under 120lb that I didn't even tiller, just roughed out with a hatchet and checked the brace shape before shooting them in.

Ash however will blow up on you if you nick a growth ring. I've had it happen at full draw. It will also absolutely not tolerate poor tiller which means many more hours spent getting a perfect shape to avoid heavy chrysalling and folding up on the belly.

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 4:28 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 28 May, 2017 4:28 pm Post subject: |

|

|

As for the sealing issue - I don't seal my yew bows. Never have, and never needed to, despite living in the UK where rain isn't forecast but simply expected. On the nice ones, or ones for customers I'll wipe them with Danish oil to bring out the colour but that doesn't do anything to protect them from moisture.

I will always seal whitewood bows however. Most traditional bowyers here who have researched and tested military weight meanewood bows use 2 part epoxy to seal them as it's so important. The current distance record for a military arrow was set using a yew bow that wasn't sealed as far as I'm aware.

Remember that Ascham is our only extant information on medieval archery - that doesn't mean he was correct  Just because he thinks it's important to do something certainly doesn't make it true. Wasn't it Ascham who said you should oil a bracer to add speed to a shot? Just because he thinks it's important to do something certainly doesn't make it true. Wasn't it Ascham who said you should oil a bracer to add speed to a shot?

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 4:03 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 4:03 am Post subject: |

|

|

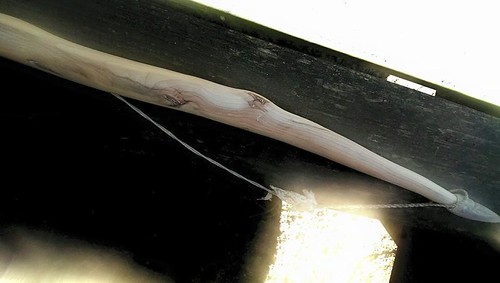

Quick example - this is a 135lb unsealed English yew replica of the Mary Rose bow MR80A0451. As you can see, on the back of the bow there's a big streak of violated heartwood showing through, along with growth rings that were cut all over the place plus of course the rotten knot that I sliced straight through. This bow is still shooting beautifully, and I wouldn't consider any of this a problem whatsoever.

This is a 95lb unsealed English yew bow that is absolutely full of rot, holes, bug damage and violated rings. Still shooting

That's the reason yew bows were so quick to make. You can get away with anything.

This however is the reason meanewood bows are so difficult. This is a large chrysal running across the belly of a fairly light (98lb) ash bow. The chrysal occurred simply because there's a tiny pin knot visible on the upper corner of the belly. These chrysals can be ignored, but eventually cause the bow to fail in compression.

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 9:40 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 9:40 am Post subject: |

|

|

Thanks Will S. for these examples of your own bow experiences.

Really interesting with the cost-benefit choice of yew if you have to equip an army. So yew both for easy and fast construction time, but also heavy handed transport on baggage trains on very uneven roads would be far safer with yew bows, than other types, where nicks could cause them to fail!

Last edited by Niels Just Rasmussen on Tue 30 May, 2017 2:14 am; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 11:13 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 11:13 am Post subject: |

|

|

Yep! It's funny really, as most professional bowyers will tell you the slightest dent or nick in the sapwood of a yew bow is game over, but in reality you could hypothetically drop a hammer on a yew bow and take a chunk out of it with no problem.

Hypothetically.

'cos I've never done that...

|

|

|

|

M. Eversberg II

|

Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 4:39 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 29 May, 2017 4:39 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I can't ever say I've thought of yew in terms of ruggedness. All the years I'd been passively milling about on pre-modern stuff and I'd assumed it just had a certain special "spring" to it.

This may be too off topic, but do these properties of yew give it anything special for the shafts of melee weaponry? I do not believe I have ever seen that referenced (usually ash or a few others, but never yew).

More to the topic, who does make decent "Mary Rose" type bows? My wife has expressed some interest in archery. We are slowly getting more involved with a early 17th century colonial history group - while longbows are basically obsolete (but still in use a bit), I'm wondering if having one as a visual sample to contrast with the matchlock might be worthwhile. Not high priority or anything, just postulating.

M.

This space for rent or lease.

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Tue 30 May, 2017 12:42 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 30 May, 2017 12:42 am Post subject: |

|

|

There's quite a few good bowyers who specialise in replicating MR bows at the moment. I make and sell them a fair bit, but not usually to order due to timber supplies. I only use English yew, whereas most other bowyers use American yew to enable them to meet order numbers.

Ian Sturgess is one of the best, along with Joe Gibbs, Ian Coote and David Pim. Some will do truly historical sidenocks and some won't. Some will use historical strings and some won't. It sort of depends on how exacting you want to be.

|

|

|

|

|

Will S

Location: Bournemouth, UK Joined: 25 Nov 2013

Posts: 170

|

Posted: Tue 30 May, 2017 12:47 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 30 May, 2017 12:47 am Post subject: |

|

|

In terms of ruggedness for shafts, yew is a softwood. It dents easily, and is pretty poor for any sort of weapon other than bows. The point here is that when it is damaged the bow doesn't fail, unlike other woods.

The reason bows had horn nocks in the first place is because yew is so soft that the bow string would cut into the timber, eventually splitting it at the nock. Hardwoods like ash, elm, hazel etc don't actually need horn nocks at all.

|

|

|

|

|

Marc Ritz

Location: Manila, Philippines Joined: 02 Aug 2013

Posts: 6

|

Posted: Fri 23 Jun, 2017 7:39 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 23 Jun, 2017 7:39 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Henry O. wrote: | | If the success of the longbow really was due to technology then why wasn't it immediately copied everywhere, and what prevented it from being invented earlier? . |

The English Longbow is the simplest bow design you can come up with. Nothing about it is in any way special. We have European self bows from the Mesolithic age which have better designs in terms of performance. Simplicity is of course a good quality, too. The deep and narrow design of English longbows maximizes the number of bows one can get out of a tree and is the quickest to build with hand tools (round surfaces are very easy to shape with hand tools rather than flat surfaces).

Yew, the tree from which English Longbows are made of, is a common bow material in Europe and in fact, it's not as important as people think it is. Yew is easy to shape and rather forgiving, that makes it easier for the bowyer. It's also preferable from an industrial standpoint to restrict oneself to one type of tree as that increases familiarity. Other bow woods do the job as well but bow designs have to be adapted to the wood.

The English Longbow wasn't just a British thing either at the time. During the Hundred Years War, the French DID invest in archers. Some French archers fought under Henry for the English even, and there have been battles won against the English due to French archers.

|

|

|

|

|

Timo Nieminen

|

Posted: Sun 25 Jun, 2017 3:14 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 25 Jun, 2017 3:14 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Marc Ritz wrote: | | The deep and narrow design of English longbows maximizes the number of bows one can get out of a tree and is the quickest to build with hand tools (round surfaces are very easy to shape with hand tools rather than flat surfaces). |

Deep and narrow also gives you more efficiency. And since you've lost efficiency from the large size, you don't want to make it worse, so take what gains to efficiency you can get.

For a military bow, you want

- cheap

- lots of energy delivered to the arrow, which you can achieve by

- High draw weight

- High energy storage for that draw weight (for a longbow, make it long)

- High efficiency (keep the limbs light)

A longbow is a fair compromise between these things, with plenty of emphasis on "cheap".

| Marc Ritz wrote: | | We have European self bows from the Mesolithic age which have better designs in terms of performance. |

Which? You have more or less D-section longbows (same performance), flatbows (less efficient) and flatbows with pseudo-siyahs (Holmegaard etc.). In principle, the last group should be able to deliver higher efficiency, but all else being the same, potentially at the cost of draw length and thus stored energy. But given that a Medieval-style longbow can get to about 200fps, that isn't easy to beat.

I haven't seen force-draw curves for Holmegaards, or energy delivered by high draw weight Holmegaards. Those would be interesting. A lot of classic military bow designs are rather mediocre at low draw weights, and only excel at high draw weights. I wonder how the Holmegaard design scales with draw weight and draw length.

(Modern Holmegaard-inspired bows can do very well, but they're not the same design as the originals.)

"In addition to being efficient, all pole arms were quite nice to look at." - Cherney Berg, A hideous history of weapons, Collier 1963.

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2026 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|