| Author |

Message |

|

Peter Spätling

Industry Professional

|

Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 12:43 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 12:43 am Post subject: |

|

|

I believe the long faulds are a fashion feature. They run completely on leather, it's no problem to mount a horse, that 's one reason why I think it has nothing to do with foot combat.

The other one is this: "Der vermeintlich gegensätzliche Trend der fortdauernden, ja fast gesteigerten Bedeutung der Ritter und des aufkommenden Söldnerwesens sowie die Professionalisierung des Krieges lassen sich an den von den Städten zu stellenden Kontingenten festmachen. Während 1435 noch von Schützen die Rede ist, werden 1443 für die Städte im Landshuter Landesteil 99 Berittene angegeben. Hierbei handelt es sich wohl fast ausschließlich um Söldner. Diese Entwicklung hin zu Schützen und einem Reiteraufgebot lässt sich auch an den Kontingenten der Stadt Regensburg auf den Hussitenfeldzügen feststellen. 1421 setzte der Regensburger Rat in der Hautpsache auf die eigenen "Spießbürger", hatte dafür 61 Spieß, wahrscheinlich Gleven, Hellebarden, Partisanen, Spießen, Piken und dergleichen als Ausrüstung angeboten; zudem ist anzunehmehn, dass die Bürger zumindest mit Helm odder zum Teil mit Harnisch ausgestattet waren. So ergänzte der Rat 1427 sein Ausgebot aus 93 Spießbürgern mit 13 Schützen und 8 Berittenen. 1431 warten es nur noch 12 Spießbürger, aber dafür 71 Armbrustschützen, 16 Handbüchsenschützen und 73 Berittene." (Ritterwelten im Spätmittelalter S. 133)

Long story short:

Regensburg 1421: 61 Pikemen

Regensburg 1427: 93 Pikemen, 13 Marksemen, 8 Rider

Regensburg 1431: 12 Pikemen, 71 Crossbowmen, 16 Handgunners, 73 Rider

The author still mentions a few more examples, but the core is: In the first half of the 15ct. the amount of riders increased in southern german armies while the amount of pikemen decreased.

Now it 's easier to fight a rider when you are on a horse yourself and fighting a crossbowman is easier, too. You are faster so he can fire less arrows at you until you reach him and can fight him.

So we have less foot combat and more mounted combat.

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 11:11 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 11:11 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Peter Spätling wrote: | I believe the long faulds are a fashion feature. They run completely on leather, it's no problem to mount a horse, that 's one reason why I think it has nothing to do with foot combat.

The other one is this: "Der vermeintlich gegensätzliche Trend der fortdauernden, ja fast gesteigerten Bedeutung der Ritter und des aufkommenden Söldnerwesens sowie die Professionalisierung des Krieges lassen sich an den von den Städten zu stellenden Kontingenten festmachen. Während 1435 noch von Schützen die Rede ist, werden 1443 für die Städte im Landshuter Landesteil 99 Berittene angegeben. Hierbei handelt es sich wohl fast ausschließlich um Söldner. Diese Entwicklung hin zu Schützen und einem Reiteraufgebot lässt sich auch an den Kontingenten der Stadt Regensburg auf den Hussitenfeldzügen feststellen. 1421 setzte der Regensburger Rat in der Hautpsache auf die eigenen "Spießbürger", hatte dafür 61 Spieß, wahrscheinlich Gleven, Hellebarden, Partisanen, Spießen, Piken und dergleichen als Ausrüstung angeboten; zudem ist anzunehmehn, dass die Bürger zumindest mit Helm odder zum Teil mit Harnisch ausgestattet waren. So ergänzte der Rat 1427 sein Ausgebot aus 93 Spießbürgern mit 13 Schützen und 8 Berittenen. 1431 warten es nur noch 12 Spießbürger, aber dafür 71 Armbrustschützen, 16 Handbüchsenschützen und 73 Berittene." (Ritterwelten im Spätmittelalter S. 133)

Long story short:

Regensburg 1421: 61 Pikemen

Regensburg 1427: 93 Pikemen, 13 Marksemen, 8 Rider

Regensburg 1431: 12 Pikemen, 71 Crossbowmen, 16 Handgunners, 73 Rider

The author still mentions a few more examples, but the core is: In the first half of the 15ct. the amount of riders increased in southern german armies while the amount of pikemen decreased.

Now it 's easier to fight a rider when you are on a horse yourself and fighting a crossbowman is easier, too. You are faster so he can fire less arrows at you until you reach him and can fight him.

So we have less foot combat and more mounted combat. |

Thanks for your info Peter.

Interesting that mobility doesn't seem to be the problem with long faulds.

It means we probably have to discard that hypothesis. So that leaves us with more leg protection - under which circumstances is it necessary or not to have long faulds?

Yet I still don't find it convincing that it should be only fashion. Long faulds comes and then goes again. At some point people must have thought that extended low protection was necessary, but then it was abandoned again as it probably was not of relevance.

Whether these long faulds were for fighting on foot OR protection more of the legs when sitting on the horse can off course be debated. What is really interesting is that it comes and goes again. So it's likely a response to some kind of change in weaponry and/or combat style. Off course new things can become fashion, but it still has to have a function as the armour. It is what protects people's lives.

Very interesting with the change from pike men to way more crossbowmen and mounted troops in the early 1400's in southern Germany. If you go fully mounted as a knight, it is perhaps more the gunners that actually can shoot through your massive armour than longbow/crossbows. When making mounted charges you can limit your time-exposure towards the enemy army.

Still is quite weird that pikemen decreases so much as they have to protect the crossbowmen/gunners from cavalry charges?

As you see on later warfare (Swedes for instance) pikemen HAS to come back in greater numbers to defend against cavalry charges. Maybe later info from Regensburg or nearby shows exactly that.

|

|

|

|

|

Peter Spätling

Industry Professional

|

Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 12:39 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 12:39 pm Post subject: |

|

|

well if you take a look at the time of Maximilian I. you can clearly see the increasing numbers of pikemen in the armies.

Also looking at armor of later date, you may notice that tassets are mostly worn by riders and not by foot soldiers. I believe that tassets were meant to close the gap between cuisses and cuirass-faulds. Which is extended when being mounted. Just take a look at Arne when he 's mounted. The only exception are the pieces from the Helmschmied workshop. But they all share high reaching cuisses, where tassets are not needed, like Mark can show you.

|

|

|

|

|

Mark Lewis

|

Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 1:52 pm Post subject: Posted: Sun 24 Jan, 2016 1:52 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Peter Spätling wrote: | | I believe the long faulds are a fashion feature. They run completely on leather, it's no problem to mount a horse, that 's one reason why I think it has nothing to do with foot combat. |

Hi Peter, I agree that fashion plays a role, but I think Tobias Capwell has made a convincing argument that practical issues are involved as well. Long faulds do not of course prevent riding, but assist in protecting the vulnerable groin and femoral arteries which are more exposed when on foot. Capwell has identified other features in English leg armour that also enhance protection of the inner leg. The extra length was tried for a short time then discarded, as un-necessary/unfashionable.

| Peter Spätling wrote: | | The author still mentions a few more examples, but the core is: In the first half of the 15ct. the amount of riders increased in southern german armies while the amount of pikemen decreased. |

That's very interesting, and the change in numbers is dramatic! Perhaps the change is related to a shift towards lighter armed cavalry, particularly mounted crossbowmen, who begin appearing frequently in art through the mid-late 15th century?

|

|

|

|

|

Peter Spätling

Industry Professional

|

Posted: Mon 25 Jan, 2016 10:14 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 25 Jan, 2016 10:14 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Mark Lewis wrote: |

Hi Peter, I agree that fashion plays a role, but I think Tobias Capwell has made a convincing argument that practical issues are involved as well. Long faulds do not of course prevent riding, but assist in protecting the vulnerable groin and femoral arteries which are more exposed when on foot. Capwell has identified other features in English leg armour that also enhance protection of the inner leg. The extra length was tried for a short time then discarded, as un-necessary/unfashionable.

|

If the groin and femoral arteries are so exposed, as you say, why did foot soldiers often don't wear any leg protection at all?

Also the laws made by the cities like Augsburg, Bretten, Landshut etc. pp. often don't mention leg armor for many of the soldiers, except guys like a master craftsman who had to own a complete suit in some cases. Even in the 16 century many Landsknechte didn't wear leg armor. If we take a look at the battle of Towton most injuries were found on the head. And if you want to protect your dick you can simply wear a brayet, which was in fashion already.

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Mon 25 Jan, 2016 12:16 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 25 Jan, 2016 12:16 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Peter Spätling wrote: | | Mark Lewis wrote: |

Hi Peter, I agree that fashion plays a role, but I think Tobias Capwell has made a convincing argument that practical issues are involved as well. Long faulds do not of course prevent riding, but assist in protecting the vulnerable groin and femoral arteries which are more exposed when on foot. Capwell has identified other features in English leg armour that also enhance protection of the inner leg. The extra length was tried for a short time then discarded, as un-necessary/unfashionable.

|

If the groin and femoral arteries are so exposed, as you say, why did foot soldiers often don't wear any leg protection at all?

Also the laws made by the cities like Augsburg, Bretten, Landshut etc. pp. often don't mention leg armor for many of the soldiers, except guys like a master craftsman who had to own a complete suit in some cases. Even in the 16 century many Landsknechte didn't wear leg armor. If we take a look at the battle of Towton most injuries were found on the head. And if you want to protect your dick you can simply wear a brayet, which was in fashion already. |

Lack of foot protection could very well be for avoiding extra weight when doing marches. If you are a mercenary foot solider you will walk a lot, so that could be the reason landsknechts apparently mostly did without.

If you are a knight with horses you can ride and then dismount for battle, it would make extensive leg protection much more probable as they don't have to march long distances. If you fight mounded extra leg protection that doesn't hinder your mobility should also be preferable.

It is interesting that the long faulds coming and going seemingly coincide with coming and going of the numbers of pikemen. Maybe that is significant?

The problem with battlefield injuries is that only the dead shows up - not the wounded.

This is pure speculation, but if you are in a melee and you have injured one enemy who is going down seemingly incapacitated from a nasty leg wound (or nasty stomach or arm wound), would you bend down or go close to him to finish him off? He is out of the fight after all? Wouldn't you orientate yourself to defend/attack a fresh targets instead of making you totally open for attacks, while wasting time of an enemy that is no longer a threat?

You see from many battles later on in european history, that you would have extensive numbers of injured people. Those losing might be hold at ransom (or executed on the spot or somewhere elsewhere) while the wounded winners would be carried away. Thus you could have far less leg injuries showing up archaeologically at the site. Execution of the losing side infantry might give an overrepresentation of head wounds (and other wounds if the execution is savage) compared to what actually happened in the battle.

My point is just that one should be quite cautious of what turns up on battlefield-graves, no matter if my speculation is utterly wrong.

|

|

|

|

|

Pieter B.

|

Posted: Mon 25 Jan, 2016 4:53 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 25 Jan, 2016 4:53 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Niels Just Rasmussen wrote: | | Peter Spätling wrote: | | Mark Lewis wrote: |

Hi Peter, I agree that fashion plays a role, but I think Tobias Capwell has made a convincing argument that practical issues are involved as well. Long faulds do not of course prevent riding, but assist in protecting the vulnerable groin and femoral arteries which are more exposed when on foot. Capwell has identified other features in English leg armour that also enhance protection of the inner leg. The extra length was tried for a short time then discarded, as un-necessary/unfashionable.

|

If the groin and femoral arteries are so exposed, as you say, why did foot soldiers often don't wear any leg protection at all?

Also the laws made by the cities like Augsburg, Bretten, Landshut etc. pp. often don't mention leg armor for many of the soldiers, except guys like a master craftsman who had to own a complete suit in some cases. Even in the 16 century many Landsknechte didn't wear leg armor. If we take a look at the battle of Towton most injuries were found on the head. And if you want to protect your dick you can simply wear a brayet, which was in fashion already. |

Lack of foot protection could very well be for avoiding extra weight when doing marches. If you are a mercenary foot solider you will walk a lot, so that could be the reason landsknechts apparently mostly did without.

If you are a knight with horses you can ride and then dismount for battle, it would make extensive leg protection much more probable as they don't have to march long distances. If you fight mounded extra leg protection that doesn't hinder your mobility should also be preferable.

It is interesting that the long faulds coming and going seemingly coincide with coming and going of the numbers of pikemen. Maybe that is significant?

The problem with battlefield injuries is that only the dead shows up - not the wounded.

This is pure speculation, but if you are in a melee and you have injured one enemy who is going down seemingly incapacitated from a nasty leg wound (or nasty stomach or arm wound), would you bend down or go close to him to finish him off? He is out of the fight after all? Wouldn't you orientate yourself to defend/attack a fresh targets instead of making you totally open for attacks, while wasting time of an enemy that is no longer a threat?

You see from many battles later on in european history, that you would have extensive numbers of injured people. Those losing might be hold at ransom (or executed on the spot or somewhere elsewhere) while the wounded winners would be carried away. Thus you could have far less leg injuries showing up archaeologically at the site. Execution of the losing side infantry might give an overrepresentation of head wounds (and other wounds if the execution is savage) compared to what actually happened in the battle.

My point is just that one should be quite cautious of what turns up on battlefield-graves, no matter if my speculation is utterly wrong. |

At the battle of Dornach around 15-20% of the dead had healed head wounds signifying that even the ones wounded in previous battles had head wounds. I am not sure if the researchers looked at the healed injuries from the Towton graves but I do recall seeing a very grim reconstruction of a person with a scar running down his entire lower jaw.

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Wed 27 Jan, 2016 6:50 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 27 Jan, 2016 6:50 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Pieter B. wrote: | | At the battle of Dornach around 15-20% of the dead had healed head wounds signifying that even the ones wounded in previous battles had head wounds. I am not sure if the researchers looked at the healed injuries from the Towton graves but I do recall seeing a very grim reconstruction of a person with a scar running down his entire lower jaw. |

That's pretty interesting statistics since if injuries showed up in skulls, they must have been fairly substantial.

Apparently your change of surviving cuts was much greater than surviving piercing wounds, most likely because if vastly increased rate of sepsis with deep puncture wounds while cuts can be cleaned more easily.

|

|

|

|

James Arlen Gillaspie

Industry Professional

Location: upstate NY Joined: 10 Nov 2005

Posts: 587

|

Posted: Wed 27 Jan, 2016 8:10 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 27 Jan, 2016 8:10 am Post subject: |

|

|

A major factor in why many infantry soldiers did not wear leg armour is cost; most infantry were really mounted infantry, and, as I like to joke, "Anybody who was walking must have diced away their nag the night before". As sick as many of Henry V's infantry were before Agincourt, they never would have got their without their mounts.

There is a natural priority to what needs to be armoured first, and legs are near the bottom of the list. Feet, of course, are dead last, and many men-at-arms on the continent (English are an exception) did not wear sabatons. If you wanted something that fit and worked properly, they were expensive, and many warriors just took their chances.

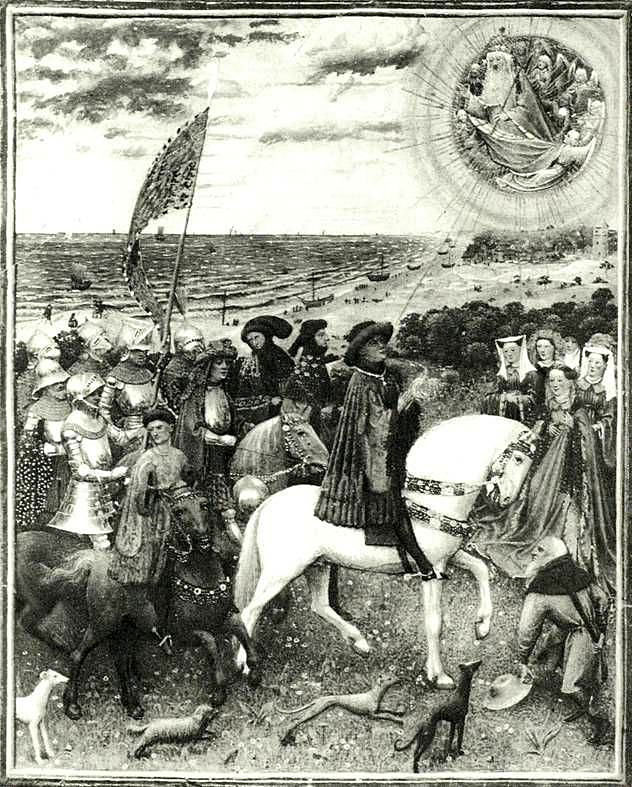

My own research has confirmed what I was told was the conclusion reached by a former member of the staff in the Arms and Armor Department in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City). The 'Kastenbrust' style is Flemish in origin and from there spread to the Holy Roman Empire. It starts out as standard globose breastplates and started becoming more angular (see the miniature in the Turin-Milan 'Book of Hours', thought to be by Huber van Eyck, 'The Sovereign's Prayer', for early breastplates that look like Kastenbrust with soft edges, and also a nice grand bacinet) until the lines became sharply defined. They were never universal, and HRE breastplates of that time are remarkable in their variety.

Attachment: 135.97 KB Attachment: 135.97 KB

jamesarlen.com

|

|

|

|

|

Pieter B.

|

Posted: Wed 27 Jan, 2016 1:18 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 27 Jan, 2016 1:18 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Niels Just Rasmussen wrote: | | Pieter B. wrote: | | At the battle of Dornach around 15-20% of the dead had healed head wounds signifying that even the ones wounded in previous battles had head wounds. I am not sure if the researchers looked at the healed injuries from the Towton graves but I do recall seeing a very grim reconstruction of a person with a scar running down his entire lower jaw. |

That's pretty interesting statistics since if injuries showed up in skulls, they must have been fairly substantial.

Apparently your change of surviving cuts was much greater than surviving piercing wounds, most likely because if vastly increased rate of sepsis with deep puncture wounds while cuts can be cleaned more easily. |

I believe some guys in the Napoleonic wars survived many saber cuts over the course of their career. There are also quite a few accounts of medieval figures with scars, I reckon that recognizing a veteran in those days wasn't to hard.

Here is an interesting article: http://hroarr.com/the-use-of-the-saber-in-the...the-saber/

As for piercing wounds, I believe De Monluc got rather lucky in this regard or he had excellent surgeons, shot a couple of times yet he never had an infected wound. I believe his memoirs include a short bit on three doctors discussing whether or not to amputate his arm, he got to keep it luckily.

|

|

|

|

|

Mark Lewis

|

Posted: Thu 28 Jan, 2016 6:03 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 28 Jan, 2016 6:03 am Post subject: |

|

|

| James Arlen Gillaspie wrote: | A major factor in why many infantry soldiers did not wear leg armour is cost; most infantry were really mounted infantry, and, as I like to joke, "Anybody who was walking must have diced away their nag the night before". As sick as many of Henry V's infantry were before Agincourt, they never would have got their without their mounts.

There is a natural priority to what needs to be armoured first, and legs are near the bottom of the list. Feet, of course, are dead last, and many men-at-arms on the continent (English are an exception) did not wear sabatons. If you wanted something that fit and worked properly, they were expensive, and many warriors just took their chances. |

Hi James, thanks for commenting, I agree completely with your assessment of the facts. Any armour is a trade-off between defense, weight, and cost... it is to be expected that recruitment requirements (as mentioned above) prioritize the more essential pieces of defense for the head and torso, and that armour for the lower limbs is the first to be dispensed with, particularly in later periods.

To clarify the point of my original comment... I simply intended to highlight the parallel (however minor) with contemporary English armour where, counter to the general trend, men-at-arms were specifically equipping themselves for combat on foot with more armour for the lower body, not less. In particular, English effigies generally include some or all of the following: longer faulds, fully enclosed cuisses, poleyns with extended coverage for the inner knee, and plate sabatons with additional reinforcement plates.

The first three features are well displayed in this example.

http://effigiesandbrasses.com/2831/2826/

The reinforcement plate for the sabaton can be seen here, attached above the usual multi-lame construction.

http://effigiesandbrasses.com/1610/1665/

For greatest contrast, we can compare with Italian armour which generally does not include these features (though Pippo Spano did bring his sabatons today.)

| James Arlen Gillaspie wrote: | | My own research has confirmed what I was told was the conclusion reached by a former member of the staff in the Arms and Armor Department in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City). The 'Kastenbrust' style is Flemish in origin and from there spread to the Holy Roman Empire. |

This is very interesting, were there any other early effigies or artworks that you found particularly compelling evidence in this regard? Another miniature I intended to share for comparison is from the Netherlands coincidentally, attributed to the Master of Catherine of Cleves, c. 1438.

http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images/10+E+1/page/1

Finally here is another example of the fan-shaped besagews (and other stylistic details) discussed earlier, from an interesting source... The Hofamterspiel is a deck of cards using the kingdoms of France, Germany, Bohemia, and Hungary as the four suits, created for Ladislaus the Posthumous. The card below is the King of Bohemia, a title which Ladislaus held himself from 1453 until his death in 1457.

http://bilddatenbank.khm.at/viewArtefact?id=91103

|

|

|

|

James Arlen Gillaspie

Industry Professional

Location: upstate NY Joined: 10 Nov 2005

Posts: 587

|

Posted: Thu 28 Jan, 2016 8:48 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 28 Jan, 2016 8:48 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Even in England, we see a lot of people showing up for muster without leg armour, especially after the Hundred Years War starts going south on them. However, I don't think any actual English man-at-arms would ever show up like that, unless he was swimming!

The characteristic skirt continues as part of the 'tonlet' armours for the tournament, apparently because it hearkens back to some heroic reference of the 'Kastenbrust' era and/or as some cultural reference to a noble tradition (court garments with the flaired skirt?).

jamesarlen.com

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Fri 29 Jan, 2016 7:27 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 29 Jan, 2016 7:27 am Post subject: |

|

|

| James Arlen Gillaspie wrote: | A major factor in why many infantry soldiers did not wear leg armour is cost; most infantry were really mounted infantry, and, as I like to joke, "Anybody who was walking must have diced away their nag the night before". As sick as many of Henry V's infantry were before Agincourt, they never would have got their without their mounts.

There is a natural priority to what needs to be armoured first, and legs are near the bottom of the list. Feet, of course, are dead last, and many men-at-arms on the continent (English are an exception) did not wear sabatons. If you wanted something that fit and worked properly, they were expensive, and many warriors just took their chances.

My own research has confirmed what I was told was the conclusion reached by a former member of the staff in the Arms and Armor Department in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City). The 'Kastenbrust' style is Flemish in origin and from there spread to the Holy Roman Empire. It starts out as standard globose breastplates and started becoming more angular (see the miniature in the Turin-Milan 'Book of Hours', thought to be by Huber van Eyck, 'The Sovereign's Prayer', for early breastplates that look like Kastenbrust with soft edges, and also a nice grand bacinet) until the lines became sharply defined. They were never universal, and HRE breastplates of that time are remarkable in their variety. |

So leg+feet armour is a pain on the march, so you really only want it if you can afford to ride as well.

I'm a bit surprised that the globular breastplates are the oldest as it seemed from the paintings that some if the oldest box-like Kastenburst already was around in the 1420's. That it originates in the Flemish area is not a surprise at all though.

So when do you have earliest images/effigies of the globular type from the Flemish area??

I ask since the material Mark Lewis have located have not shown any clearly globular types being clearly earlier than the boxed types?

| Pieter B. wrote: |

I believe some guys in the Napoleonic wars survived many saber cuts over the course of their career. There are also quite a few accounts of medieval figures with scars, I reckon that recognizing a veteran in those days wasn't to hard.

Here is an interesting article: http://hroarr.com/the-use-of-the-saber-in-the...the-saber/

As for piercing wounds, I believe De Monluc got rather lucky in this regard or he had excellent surgeons, shot a couple of times yet he never had an infected wound. I believe his memoirs include a short bit on three doctors discussing whether or not to amputate his arm, he got to keep it luckily. |

Yeah - in my thread about a Danish sabers I found also description of the Danish dragoon units going for the heads of the Prussian hussars at "Rytterfægtningen ved Århus" (1849) as described by Ritmester Søren Barth.

Of 40 Germans hussars wounded receiving head wounds and being still alive while being transported to the hospital, 29 of them had died the next day!

Source: http://myArmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.php?t=30820&highlight=

Some soldiers clearly must have survived with awful scars.

I think you are right that for surviving piercing wounds you needed good doctors and mostly only the rich had that.

(some areas could off course have local wound experts and some rich people acquired quack-doctors, so it was perhaps not always clear cut between rich and poor).

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 7:02 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 7:02 am Post subject: |

|

|

Found another quite late Kastenbrust from Denmark.

This late gothic image from Vrangstrup Kirke on Sjælland is of Sankt Jørgen (Saint George) fighting the dragon is dated 1490-1500.

Jørgen seems to be in a box-like Kastenbrust and also faintly a two-handed sword is hanging from his horse?

Attachment: 112.43 KB Attachment: 112.43 KB

Sankt Jørgen with Kastenbrust and two-hander.

Vrangstrup Kirke - dated 1490-1500.

Source: http://natmus.dk/salg-og-ydelser/museumsfaglige-ydelser/kirker-og-kirkegaarde/kalkmalerier-i-danske-kirker/

|

|

|

|

|

Pieter B.

|

Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 7:19 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 7:19 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Niels Just Rasmussen wrote: |

Yeah - in my thread about a Danish sabers I found also description of the Danish dragoon units going for the heads of the Prussian hussars at "Rytterfægtningen ved Århus" (1849) as described by Ritmester Søren Barth.

Of 40 Germans hussars wounded receiving head wounds and being still alive while being transported to the hospital, 29 of them had died the next day!

Source: http://myArmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.php?t=30820&highlight=

Some soldiers clearly must have survived with awful scars.

I think you are right that for surviving piercing wounds you needed good doctors and mostly only the rich had that.

(some areas could off course have local wound experts and some rich people acquired quack-doctors, so it was perhaps not always clear cut between rich and poor). |

A poor medieval soldier was still a comparatively rich man so it's all relative. That said I do believe Flemish cities often had their city militia organized by guilds and said guilds could also be responsible for providing barber surgeons to serve under their banner. Then again those guild members probably had an income above the 50% percentile of a given city anyways.

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 7:28 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 7:28 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Pieter B. wrote: | | Niels Just Rasmussen wrote: |

Yeah - in my thread about a Danish sabers I found also description of the Danish dragoon units going for the heads of the Prussian hussars at "Rytterfægtningen ved Århus" (1849) as described by Ritmester Søren Barth.

Of 40 Germans hussars wounded receiving head wounds and being still alive while being transported to the hospital, 29 of them had died the next day!

Source: http://myArmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.php?t=30820&highlight=

Some soldiers clearly must have survived with awful scars.

I think you are right that for surviving piercing wounds you needed good doctors and mostly only the rich had that.

(some areas could off course have local wound experts and some rich people acquired quack-doctors, so it was perhaps not always clear cut between rich and poor). |

A poor medieval soldier was still a comparatively rich man so it's all relative. That said I do believe Flemish cities often had their city militia organized by guilds and said guilds could also be responsible for providing barber surgeons to serve under their banner. Then again those guild members probably had an income above the 50% percentile of a given city anyways. |

Good points. So its more forced-drafted peasants (drafted by their local nobleman for campaigns), who didn't have the funds to pay for the "security" of being a guild member (or didn't have any guilds around for that matter), that would be in trouble if injured.

Being rich is never enough protection against being fooled by quacks if you are not critical, but at least you have a broader choice of experts to choose from.

|

|

|

|

|

Pieter B.

|

Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 8:31 am Post subject: Posted: Sun 06 Mar, 2016 8:31 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Niels Just Rasmussen wrote: | Good points. So its more forced-drafted peasants (drafted by their local nobleman for campaigns), who didn't have the funds to pay for the "security" of being a guild member (or didn't have any guilds around for that matter), that would be in trouble if injured.

Being rich is never enough protection against being fooled by quacks if you are not critical, but at least you have a broader choice of experts to choose from. |

How would one actually go about determining who was rich when the battlefield was filled with the dead and dying stripped naked? I recall reading about the battle of Montlhéry where the author and the duke of Burgundy found a wounded naked man in the camp who identified himself as an archer of the guard and was given prompt medical attention and then recovered. Had he not been identified it's possible he could have perished regardless of his status.

A second point I would like to raise is that while your 'drafted peasant' might only have had logistical and medical support as far as his captain provided he could still be a well earning member of his community. However this is not really the topic of the thread and I won't attempt to derail it further.

I'm afraid I live a bit to northerly to provide you with any pictures of Flemish effigy's. I do wonder if any breastplates were exported across the Channel to England or more to the south into France.

|

|

|

|

|

Mark Lewis

|

|

|

|

|

Niels Just Rasmussen

|

Posted: Tue 08 Mar, 2016 10:08 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 08 Mar, 2016 10:08 am Post subject: |

|

|

We have both Gierslev Kirke (1475-1525) and Vrangstrup Kirke (1490-1500) from Sjælland showing very late depictions of boxed Kastenbrust. The painting style seems quite different for these two churches, so its most likely that Kastenburst were still in use by some noblemen here, whereas the more prominent centers such as Aarhus could portray newest "fashion" armour (likely imported master painters from Germany?).

This is in itself very interesting as the evidence for very late (~1500) boxed Kastenbrust in Denmark seems to be growing if the dating of these two churches are correct - it is more likely as the dating has to do with the style of the paintings and not based on weapons or armour (so independent of that).

| Pieter B. wrote: |

How would one actually go about determining who was rich when the battlefield was filled with the dead and dying stripped naked? I recall reading about the battle of Montlhéry where the author and the duke of Burgundy found a wounded naked man in the camp who identified himself as an archer of the guard and was given prompt medical attention and then recovered. Had he not been identified it's possible he could have perished regardless of his status.

A second point I would like to raise is that while your 'drafted peasant' might only have had logistical and medical support as far as his captain provided he could still be a well earning member of his community. However this is not really the topic of the thread and I won't attempt to derail it further.

I'm afraid I live a bit to northerly to provide you with any pictures of Flemish effigy's. I do wonder if any breastplates were exported across the Channel to England or more to the south into France. |

Only the losers of the battle would risk being stripped naked (?) unless a slayer battle happened in neutral territory with local people killing and stealing from both groups before our soldiers arrived at the scene. If one group held the field after battle they would tend to their own people and probably take more wealthy soldiers of the enemy hostage.

[If you have two mercenary armies facing each other, then locals would have no ties to either group and possibly had been harassed by both - but that is more Renaissance than medieval periods.]

It was very important to "look rich" on the battlefield, so people would ransom you instead of killing you - poor people being injured would just make you lose money, while an enemy noble probably would get attention, so you could earn an income keeping him alive for ransom.

Rich nobles in the middle ages would probably have squires, servants and a private physician waiting at the baggage train, so they would off course arrive to tend their noble straight after the battle?!

|

|

|

|

|

T. Kew

Location: London, UK Joined: 21 Apr 2012

Posts: 256

|

Posted: Wed 09 Mar, 2016 4:37 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 09 Mar, 2016 4:37 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I happened to be strolling through the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow on Monday, and turned a corner to find this rather lovely piece:

A.1981.40.a

I've popped the rest of my photos into this Dropbox album, which should hopefully be viewable - let me know if not.

It's a rather nice example of a late Kastenbrust - apparently the rear fauld is not original, but the rest of the cuirass is (it wasn't clear whether that also applies to the spaulders).

HEMA fencer and coach, New Cross Historical Fencing

Last edited by T. Kew on Fri 11 Mar, 2016 2:53 pm; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2024 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|