Posts: 1,757 Location: Storvreta, Sweden

Sat 06 Apr, 2013 1:19 am

Hi Jeffrey,

Evidence for my hypothesis is circumstantial.

The hypothesis has not been presented in its full yet, nor have I presented the full process of analysis nor all the criteria I use to evaluate if a swords seems to be the result of geometric design or not. I shall return to this in articles on my home page and perhaps in a larger publication.

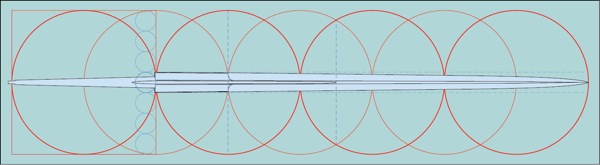

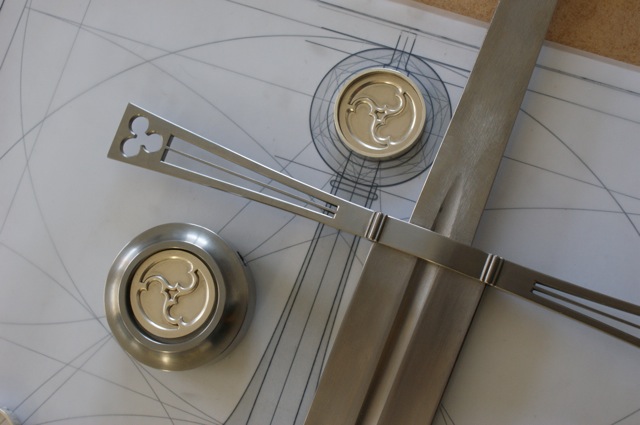

The method I use follows the same techniques and principles of development as the geometric drawings used as the basis for abbeys, churches and cathedrals. Those are the most well preserved and detailed construction drawings we have from the period.

We know that other craftsmen used geometric drawing to plan, design and lay out their work but there is very little surviving of the actual drawings themselves. Geometric drawing has ancient traditions among artist, artisans and engineers. It is telling that the one of the best sources on architecture in the classical period is by Vitruvius. He was not just an architect, but a military engineer who followed Julius Caesar on his gallic wars. Even though Vitruvius was a rather dry and very practical minded person, he also hints at some aspects of geometry that has to do with Manīs place in Cosmos. Geometry was a way to get things *right* on many levels, both practical and esoteric.

Some late 15th century handbooks in geometric design tell about the methods used by master stone masons and goldsmiths. Theophilus also describe the use of the compass and straight edge in layout work.

Why use geometry in the making of swords? Isnīt it just a complicated and roundabout way to reach a simple solution?

-To us it might seem so since we do not have the direct practical need to learn its use in our modern world. We are not familiar with the simple handling of the tools used in drawing and the thought processes involved might seem arcane and complex.

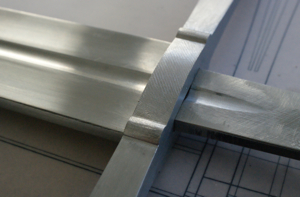

If we are making just one sword, that may well be the case, but if we think about how swords were produced in large numbers and how labour was divided between several specialist craftsmen it is more evident that a system for specification of parts is not only practical but perhaps even necessary.

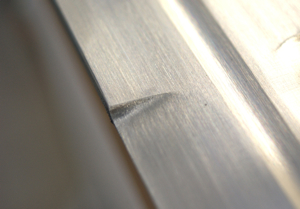

It is easy to take he shape of the medieval sword for granted. Its form is so strong and simple. Yet it is also subtle. When we look at contemporary attempts to replicate medieval swords we see how easy it is to get it wrong.

-A "simple" sword with straight guard and brazil nut pommel is just that, isnīt it: a long blade with a hilt consisting of a grip and straight guard and a lenticular shaped bob of iron.

Yet, when we compare contemporary attempts with the original swords they often seem to lack something. They are often slightly "out of tune" somehow.

In a time when many craftsmen may have been illiterate, when there were no internationally shared standards of measurements then geometric drawing is a very handy method to set out dimensions and convey to others the principles of a design. Knowledge in geometric drawing does not mean you have to be literate. You do not have to have a university degree to learn it. You can learn its use and application merely by watching it being preformed by someone who knows it. It is in fact rather easy to learn even though there are some specific rules to follow. This is probably how this knowledge was imparted to new generations of craftsmen.

Geometric designs are easy to memorize. They are easy to duplicate. You can easily scale the product to any dimension based on a geometric design. There is no need to round of measurements: you can take them directly from a drawing: this takes away the need to express dimensions in fractions of measure units.

So far I have analyzed some 80+ swords. Many do seem to follow a geometric plan for their proportions but not all. You cannot stretch the basic grid to fit just any sword. There is in fact a rather narrow margin where swords fit all the restrictions of a geometric plan.

What I have seen from 11th to 16th century swords hints that there is a pattern and perhaps even an evolution of the use of geometry.

-But, *much* more work is needed on the hypothesis as well as more critical evaluation.

What I propose is rather main stream in other fields of art history. It is just that these ideas has never before been applied to the study of swords.

On my home page there are some more articles on this theme, if you are interested. There are also two articles published in print: the Park Lane Arms Fair catalogue of 2012 has a presentation of three swords, and the catalogue to the exhibit at the

Wallace Collection: "The Noble Art of the Sword" has one article presenting the geometry of three swords in the Wallace Collection.