| which warfare style/ period was 'more bloody' |

| medieval |

|

18% |

[ 8 ] |

| renaissance/ early modern warfare. |

|

81% |

[ 35 ] |

|

| Total Votes : 43 |

|

| Author |

Message |

|

Lafayette C Curtis

|

Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 1:57 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 1:57 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Timo Nieminen wrote: | | Renaissance/EM warfare was much more battle-oriented in comparison to atrocity-oriented Medieval warfare. |

I wouldn't be so sure about that. Atrocities by Renaissance armies outside the battlefield happened all the time; paintings and woodcuts of the period depict soldiers ravaging the countryside so frequently that it's virtually a stock subject, and the cruelties perpetrated during the Thirty Years' War were such that they were still remembered in folktales (and similar artifacts of vernacular cultural memory) and brought back to the fore during the Soviet invasion of Germany at the end of World War II. Some of the precautions used by the late- and post-WW2 German rural population to secure their supplies and womenfolk from Soviet soldiers were copied almost verbatim from this cultural memory about the 30YW.

|

|

|

|

|

Lafayette C Curtis

|

Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 2:11 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 2:11 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Matthew Amt wrote: | | Even in the 18th century, with firearms much more effective and efficient than those used in the Renaissance |

The folks at Graz in Austria experimented with samples from their rich store of gunpowder weapons in 1988-1989 and found that--of the arms in their collection--there was no material improvement in quality from the 16th to the 18th century, and in fact the finest 16th-century guns were substantially more accurate than mass-produced 18th-century infantry muskets. This hasn't even taken account of the larger windages (gap between ball and barrel) usually permitted in 18th-century muskets, which further reduced their accuracy. I'd speculate that while Renaissance musketeers and arquebusiers fired far fewer shots within a given amount of time than their 19th-century counterparts, they were able to make more of their shots count and the effects as a whole cancelled each other out; later military commanders may have chosen to emphasise reloading speed over accuracy not because it gave better results overall but because it was a cheaper way of achieving the same results at a time when labour costs (including soldiers' pay) were rising while capital/material costs (including the price of firearms and ammunition) were gradually falling.

|

|

|

|

|

Timo Nieminen

|

Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 8:19 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 8:19 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Lafayette C Curtis wrote: | | Timo Nieminen wrote: | | Renaissance/EM warfare was much more battle-oriented in comparison to atrocity-oriented Medieval warfare. |

I wouldn't be so sure about that. Atrocities by Renaissance armies outside the battlefield happened all the time; paintings and woodcuts of the period depict soldiers ravaging the countryside so frequently that it's virtually a stock subject, and the cruelties perpetrated during the Thirty Years' War were such that they were still remembered in folktales (and similar artifacts of vernacular cultural memory) and brought back to the fore during the Soviet invasion of Germany at the end of World War II. Some of the precautions used by the late- and post-WW2 German rural population to secure their supplies and womenfolk from Soviet soldiers were copied almost verbatim from this cultural memory about the 30YW. |

For sure, plenty of devastation by Renaissance armies. A lot of this was simply the army feeding itself as it moved (or stayed in one place). Any place the armies moved through suffered, whether friendly, enemy or neutral territory. (Similar problems with Qing armies, even in friendly territory, if the army stayed in place long enough to exhaust local supplies.)

But compare this with Medieval warfare, where often the sole aim was to devastate enemy territory. Not just feed yourself, but to systematically destroy as much as possible - kill farmers, burn crops. While avoiding battle with the enemy army. At least Renaissance armies, often enough, were moving with intent to fight the enemy army.

Systematic Swedish looting in the 30YW - which is a major culprit in the memories of destruction - was partly aimed at pressuring the enemy to accept Swedish terms in the ongoing peace talks, but also partly just to get the loot that was required to pay the Swedish army.

"In addition to being efficient, all pole arms were quite nice to look at." - Cherney Berg, A hideous history of weapons, Collier 1963.

|

|

|

|

|

William P

|

Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 8:27 pm Post subject: Posted: Wed 11 Jul, 2012 8:27 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Timo Nieminen wrote: | | Lafayette C Curtis wrote: | | Timo Nieminen wrote: | | Renaissance/EM warfare was much more battle-oriented in comparison to atrocity-oriented Medieval warfare. |

I wouldn't be so sure about that. Atrocities by Renaissance armies outside the battlefield happened all the time; paintings and woodcuts of the period depict soldiers ravaging the countryside so frequently that it's virtually a stock subject, and the cruelties perpetrated during the Thirty Years' War were such that they were still remembered in folktales (and similar artifacts of vernacular cultural memory) and brought back to the fore during the Soviet invasion of Germany at the end of World War II. Some of the precautions used by the late- and post-WW2 German rural population to secure their supplies and womenfolk from Soviet soldiers were copied almost verbatim from this cultural memory about the 30YW. |

For sure, plenty of devastation by Renaissance armies. A lot of this was simply the army feeding itself as it moved (or stayed in one place). Any place the armies moved through suffered, whether friendly, enemy or neutral territory. (Similar problems with Qing armies, even in friendly territory, if the army stayed in place long enough to exhaust local supplies.)

But compare this with Medieval warfare, where often the sole aim was to devastate enemy territory. Not just feed yourself, but to systematically destroy as much as possible - kill farmers, burn crops. While avoiding battle with the enemy army. At least Renaissance armies, often enough, were moving with intent to fight the enemy army.

Systematic Swedish looting in the 30YW - which is a major culprit in the memories of destruction - was partly aimed at pressuring the enemy to accept Swedish terms in the ongoing peace talks, but also partly just to get the loot that was required to pay the Swedish army. |

i remember hearing about something not dissimilar in the Hellenistic period or maybe the peleponesian war where a commander gave his men specially shaped shafts that were DESIGNED to destroy and ruin wheat.

he pelleponesian war was also alot more of a 'ravage the countryside style strategies

|

|

|

|

|

Lafayette C Curtis

|

Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 2:38 am Post subject: Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 2:38 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Timo Nieminen wrote: | But compare this with Medieval warfare, where often the sole aim was to devastate enemy territory. Not just feed yourself, but to systematically destroy as much as possible - kill farmers, burn crops. While avoiding battle with the enemy army. At least Renaissance armies, often enough, were moving with intent to fight the enemy army.

Systematic Swedish looting in the 30YW - which is a major culprit in the memories of destruction - was partly aimed at pressuring the enemy to accept Swedish terms in the ongoing peace talks, but also partly just to get the loot that was required to pay the Swedish army. |

Are we really sure that Renaissance armies were that eager to meet and fight the enemy army? Such was the case, perhaps, in the first half of the 16th century--after gunpowder-based siege weapons proved their superiority over medieval fortification and before the new model of low, thick, bastioned Renaissance fortification became sufficiently common to force armies to hunker down for prepare for long sieges once more. After this battle-intensive period, however, manoeuvre and territorial strategies reasserted their importance, and ravaging the countryside while avoiding battle was exactly the kind of strategy pursued by many armies--not just those of the Swedes--for much of the Thirty Years' War (especially the second half). Civilian memoirs from the era make it clear that the Swedes and the mercenaries in their employ were not the only perpetrators of widespread atrocities; if anything, they merely set an example of more brutal and more extensive ravaging practices, which everybody else then learned and copied (and "improved" upon).

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 1:40 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 1:40 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I think the OP is actually somewhat correct, though it would be hard to prove - you'd have to make a whole long series of youtube videos, not that it might not be a worth-while thing to do if you had the time and the patience.

There are a couple of differences between warfare warfare, very generally, in the Medieval period, and in the early modern period.

But before I get into that it's important to make two points.

First it's very dangerous to generalize according to European history. The reality in Spain was different from the reality in England which was different from the reality in Poland and so on.

Second it's dangerous to generalize across such vast time scales, people debate the meaning of the term Medieval, some would take that back all the way to the 6th or 7th Century, others would start after Charlemagne, or the Battle of Hastings, or somewhere else more or less arbitrarily. I've noticed from talking to people in various countries each education system seems to have a different arbitrary cut-off point. Though you narrowed it down a bit, it's still a rather long period of time.

So with those two strong caveats, very generally speaking you do see some changes between these time periods. In the Medieval period, you have many more and much smaller and weaker states. The Kingdoms are unstable and incapable of fully controlling their territory, especially any major vassals or cities which were fortified. Defensive warfare was still dominant. Armies tended to be 'skilled labor' in the sense that they were mostly professional or semi-professional warriors. This was not by any means limited to knights, incidentally.

Because there were fewer very large States, there were fewer really large-scale invasions. War tended to be on a smaller scale, for the most part (though there were many exceptions to this, such as the various Crusades). This didn't mean it was all raiding or that the peasants suffered excessively compared to the Early Modern period. That depended greatly on the nature of the war, and on the terrain, and on the peasants. The war varied in what rules it had, and yes they did have rules, sometimes quite complex and strict ones. The terrain varied from accessible to inaccessible. War in the mountains, deep forests, forested hills and swamps was different from war in the open rolling open hills, large cultivated valleys or plains. And the peasants varied, most were pretty easy to prey upon, others, such as the Swiss, or the Dithmarshers in Saxony, or the Bohemians or Dalarna Swedes, or the Ukranian Cossacks, were dangerous to mess with.

There is a myth that only knights were ever ransomed or paroled, but this wasn't true. Anyone with money could be ransomed and quite often were. Quite often large numbers of ordinary soldiers, militia and mercenaries who didn't have money were pardoned or paroled. In other cases they may be sold into slavery. I can cite some examples from the Baltic region. As an example of the former case, after the Battle of Grunwald / Tannenburg in 1410, King Jogaila of Poland paroled 14,000 German, Czech, Scottish and Danish troops on the Teutonic Order's side of the battle, most of whom went home without paying a dime in ransom, under the condition that they would report later to Krakow and swear an oath not to attack the Poles. As an example of the latter, during the Northern Crusades 6,000 Samogitians were captured at the battle of Medewage in 1329. At the insistence of King John of Bohemia, who was on the Crusade with the Teutonic Knights, these people were spared and many of them were made into serfs.

Crusades, of which a large number were conducted within Europe (by Europeans against Europeans), tended to be much more vicious and cruel. Most of the wholesale city massacres that I know off which took place during the Medieval era were done during Crusades, such as Beziers during the Albigensian Crusade. Where as later during the Early Modern period sometimes troops just got out of hand and decided to 'kill' a city out of pent up frustration, such as when Spanish and German troops sacked Rome in 1527, killing most of the population. Or Magdeburg during the 30 Years War.

But on the flip-side, with smaller local conflicts, over time sometimes the violence became more controlled and limited. This wasn't always the case mind you - local conflicts could be very nasty. But just as we know that in the EM period Italian Condottieri companies could sometimes, among each other, reach an understanding not to make the fight 'too bloody' (though this type of rule did not typically extend to foreign invaders like the Spanish or French), this also happened between neighbors in the Medieval period. One specific reason for this which emerged in the second half of the 14th Century was plague. "Scorched earth" tactics led directly to famine, and famine, apparently, led to plague, or at any rate there was a perceived link in the Medieval mind. So for example during the Hunger War in 1414, in the aftermath of Grunwald, both the Poles and the Teutonic Knights engaged in scorched earth tactics. This led to six years of plague cost the Teutonic Knights 86 of their Ritterbruden, compared to a loss of 400 at Grunwald. Unacceptable situation for them. It led to the ouster of a Grand Master, and a truce with Poland which among other things, stipulated rules for warfare which continued between them intermittently throughout the 15th Century.

Local truces also happened frequently during temporary or permanent interregnums. Many Royal or Princely families in Central Europe simply died out, such as the Piast dynasty in Poland and the Přemyslid dynasty in Bohemia, or the Zähringen family in Switzerland. For that matter, much of the Holy Roman Empire and the rest of Central, Northern, and Southern Europe could be thought of as a 'failed state' at one time or another. When this happened, each estate within the area immediately sought to improve their station, reduce their obligations and increase their rights, often at the expense of each other. Because defense was generally stronger than offense, especially defense of fortified towns or castles, or occupation off difficult terrain such as mountains, forests and swamps... a stalemate was often reached between the most powerful estates. This could either lead to a permanent or long-lasting state of petty war and raiding, such as you sometimes saw on the border between Scotland and England, between English controlled and French controlled zones during the 100 year war, or on the European borders with the Turks and Tartars, or between the Teutonic Knights and the pagan Lithuanians and so on. But generally speaking this kind of thing was bad for business. Unless there were mighty princely powers keeping the war going, or there was an insurmountable religious / cultural / affinity network barrier, it often made more sense economically to make a permanent truce between the powers. After 1348 -1350 the added impetus of fear of plague also lent strength to the latter course. These permanent truces were called Landfrieden by the Germans or Landfryd by the Poles and the Czechs. They were councils between the powerful estates in a given region, the princes, the free cities, the untamed clans, the prelates (Bishops, Archbishops, Abbots and so on). There were very big ones like the diet (Reichstag) of the Holy Roman Empire, and dozens, or hundreds of smaller ones, like the Swiss Confederacy or the Lusatian League.

In German law there were two kinds of war, Fehde, and Krieg. Fehde is 'private war', ostensibly between equals. Under the landfrieden there were rules about private war. You were not supposed to attack people on the Royal or Imperial roads, you were not supposed to harm women or children, merchants, hunters, farmers or fishermen plying their trade, you were not supposed to destroy mills or bridges, and so on. Violating these rules put all hands against you, and 'justices of the peace of the roads' were empowered to hang offenders.

Even in areas without strong landfrieden, sometimes simple economics dictated a decrease in violence. A robber knight could either slaughter and kidnap a merchant caravan passing below his keep, gaining treasure once and then growing bored as the caravans found another route... or he could 'tax' the caravan with a fee, low enough to allow them to keep coming by, but guaranteeing a constant source of income.

In the Early modern period, gunpowder (corned powder mid-15th C) had become more reliable and manageable (you didn't have to mix it in the field). Pike tactics had been refined to the point that rather poorly trained troops could still be useful. Mercenaries no longer had to be well trained urban militia or dangerous clansmen, but could be trained fairly quickly. Armies got a lot bigger. Meanwhile the discoveries of the New World and the spice trade from the Pacific vastly enriched all the Atlantic powers, initially Portugal, Spain, France, and England, (and later Holland as well...) the fist four were all strong centralized monarchies. The ruling families of these nations prosecuted huge wars to gain control of the wealthy but still independent towns of Italy and the Low Countries. The scale of war got bigger thanks to Inca silver and Indonesian nutmeg. At the same time, new diseases hit Europe as well as the New World (Syphilis and Typhus arrived in the Early modern period) and the vast religious schism of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation started a whole new series of Crusades by Europeans against Europeans. War became nastier.

I think you could make a case that the 15th Century was, very generally speaking at least in the center of Europe, more prosperous, more free and less violent than the 17th. But it would take a lot of youtube videos! :P

J

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Timo Nieminen

|

Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 2:32 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 2:32 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Lafayette C Curtis wrote: | | Timo Nieminen wrote: | But compare this with Medieval warfare, where often the sole aim was to devastate enemy territory. Not just feed yourself, but to systematically destroy as much as possible - kill farmers, burn crops. While avoiding battle with the enemy army. At least Renaissance armies, often enough, were moving with intent to fight the enemy army.

Systematic Swedish looting in the 30YW - which is a major culprit in the memories of destruction - was partly aimed at pressuring the enemy to accept Swedish terms in the ongoing peace talks, but also partly just to get the loot that was required to pay the Swedish army. |

Are we really sure that Renaissance armies were that eager to meet and fight the enemy army? |

Those paying the bill were keen on battle, and short wars. The immense expense of keeping armies in action left little choice. Even an expensive siege was cheaper than a protracted war. Not that battles or sieges were guaranteed to end wars, even if successful, but raid and counter-raid doesn't produce quick outcomes.

Ivan the Terrible's invasion of Livonia is a good example. He tried to extort 40,000 thalers. The Livonians refused, so he invaded. The initial war expenses for the Livonians, which might have been sufficient for a very short war, came to 60,000 thalers. The war didn't end, and it cost them hundreds of thousands of thalers in the end, just to run the war, not counting any damages.

| Lafayette C Curtis wrote: | | Such was the case, perhaps, in the first half of the 16th century--after gunpowder-based siege weapons proved their superiority over medieval fortification and before the new model of low, thick, bastioned Renaissance fortification became sufficiently common to force armies to hunker down for prepare for long sieges once more. After this battle-intensive period, however, manoeuvre and territorial strategies reasserted their importance, and ravaging the countryside while avoiding battle was exactly the kind of strategy pursued by many armies--not just those of the Swedes--for much of the Thirty Years' War (especially the second half). Civilian memoirs from the era make it clear that the Swedes and the mercenaries in their employ were not the only perpetrators of widespread atrocities; if anything, they merely set an example of more brutal and more extensive ravaging practices, which everybody else then learned and copied (and "improved" upon). |

The transition from feudal armies to professional armies that would stay in the field after 40 days at least meant that one could successfully capture forts/cities through siege. Star forts could be taken, systematically, but needed time to dig, men, and artillery, all of which means it needed vast amounts of money. Defending them wasn't cheap, either.

The 2nd half of the 30YW was the "quiet" half. A lot of the major players were earnestly engaged in peace talks. Financial exhaustion ruled. They wanted to stop fighting, but nobody was willing to "lose" by quitting, nobody could win, and the peace talks dragged on. Meanwhile, the armies acted in their locust-like way, and unemployed mercenaries made their living as bandits.

The destruction was enormous compared to Medieval wars, but the scale of the 30YW was enormous compared to Medieval wars. Does one measure "bloody" in absolute terms or relative terms?

"In addition to being efficient, all pole arms were quite nice to look at." - Cherney Berg, A hideous history of weapons, Collier 1963.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 3:00 pm Post subject: Posted: Thu 12 Jul, 2012 3:00 pm Post subject: |

|

|

It's worth noting that mercenary armies went back much further than the EM period. Most of the larger wars in the 14th and 15th Centuries in Central and Southern Europe involved mercenaries.

Castles and fortifications could be defeated by a well equipped Medieval army. The famous and intimidating Krak des Chevaliers

..was 'kracked' by Baibers in 1271 after only a 36 day siege, by tunneling. This was the normal way castles were taken, but it required having trained experts (sappers) and equipment.

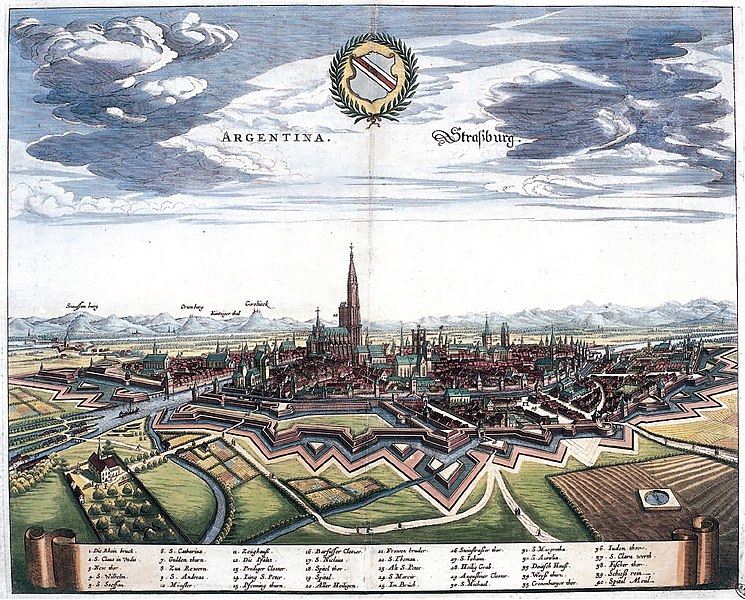

Castles built on very hard rock could be more or less immune to this type of attack, but more commonly, any fortified position surrounded by a large natural water source was beyond the abilities of sappers engineering in that time, so you had to do it the hard way- over the walls. Not coincidentally, most of the major towns were positioned on rivers. This is why so many of them proved so difficult to capture through the Middle Ages - and into the EM period, like Strasburg here with the star-fort type fortications.

Cannons made some castles and towns suddenly vulnerable, but many others were not. Towns in particular were able to buy a lot of cannons quickly and had the expertise to make them and the best available powder. By 1380 many cities had heavy ordinance at their disposal, and they spent a fortune getting 'gunpowder ready'. In 1379 Cologne spent 82% of their budget on defense, mostly cannon, and Rostock spent between 76 and 80% in 1437.

Some forts which never got the star-fortification redesign treatment remained virtually invulnerable, mostly based on their canon and their un-excavatable substrate. The Teutonic Orders castle at Malbork endured numerous sieges, sometimes for years on end, and I don't think it was ever stormed (though it changed hands many times).

Many of these sites remained invulnerable for centuries after the advent of corned powder and cast cannon barrels. I think we tend to oversimplify the transformation from 'feudal levies' to cannon and gun warfare. It was far more complex than that.

J

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

Daniel Staberg

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 2:47 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 2:47 am Post subject: |

|

|

Jean,

Malbork/Marienburg is a poor example as it never resisted a "modern" attack in it's original medieval shape, indeed it faced little or no hostile action for 160 years after being taken over by the Poles in 1466.

In the summer of 1626 Gustavus Adolphus arrived with a small Swedish army which stormed the castle in a matter of hours. The neglected state of the obsolete defences and the small garrison made it indefensible even against an modern infantry assault conducted without artillery support. The Swedes reinforced the defences by adding massive earthworks in the Dutch style around the town & castle, without them it would have been impossible to hold the castle against any attacker with modern artillery.

in 1656 the Swedes were back as part of the "Swedish Deluge" of Poland 1655-1660, this time the castle had a proper garrison as well as a resolut commander in the shape of Jakub Weyher. Yet he could do little to prevent the Swedes from taking the town and establish batteries close to the castle, within days two gates had been shattered by the Swedish artillery and it was impossible for the defenders to keep the flanking towers manned due to the hail of round shot crashing through the walls. Mortar fire ravaged the interior of the castle and it was soon clear to Weyher than his only hope was for a relife force to break the Swedish siege. 21 days after the arrival of the Swedes Weyher surrendered on terms, the castle could have been take faster but the Swedish commander had been under orders not to waste his infantry in assaults. Again the Swedes construced massive modern earthworks around the town & castle and it was these which allowed the Swedes to hold out in Marienburg until the war ended in 1660

"There is nothing more hazardous than to venture a battle. One can lose it

by a thousand unforseen circumstances, even when one has thorougly taken all

precautions that the most perfect military skill allows for."

-Fieldmarshal Lennart Torstensson.

|

|

|

|

|

William P

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 4:57 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 4:57 am Post subject: |

|

|

jean, thats a really good pair of posts, to say how complex the period REALLY was how much variaion there was,

of course im gonna limit my video number for the sake of simplicity

as mentioned m mosly going o a first talk about how warfare in terms of bttlefield tactics and weaponry + fortress design changed, plus abit saying how the wars didnt really stop, etc,

its only gonna be a couple of videos ive got one made already talking about the term 'the dark ages' saying where the erm came from, and how the medieval period was compaed to how people think it was, particularly in the areas of

interesting you mention incan silver though'

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjhIzemLdos&feature=g-all-u

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 7:57 am Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 7:57 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Daniel Staberg wrote: | Jean,

Malbork/Marienburg is a poor example as it never resisted a "modern" attack in it's original medieval shape, indeed it faced little or no hostile action for 160 years after being taken over by the Poles in 1466. |

Yes but it all depends on what you mean by 'modern' Malbork faced 6 sieges (successfully) from well equipped armies between 1410-1466. This is a (19th Century) depiction of the Polish shooting at Malbork in the 1410 siege:

The sieges during the 13 Years were much more well-equipped of course, cannon in that part of the world had advanced fast thanks to the Hussites... and several times the town was captured while the fort held out for years.

| Quote: | | In the summer of 1626 Gustavus Adolphus arrived with a small Swedish army which stormed the castle in a matter of hours. The neglected state of the obsolete defences |

True, but as you pointed out this was after 160 years of neglect and as you noted, a very small garrison. Malbork / Marienburg had been on the wrong side of the 13 Years War and was economically out of the mainstream during the Polish Renaissance and didn't have the money or the interest to keep up their defenses - of which I think the critical factor was actually the cannon not star fortification.

During the period you referred to, in warfare against the Swedes in 1655 at the siege of Jasna Góra Monastery, (a relatively obsolete fortification by the standards of the time), the issue was cannon and the size of the cannon available to the defenders vs. the attackers. When both sides had the same size guns (12 lbers), it was a stalemate. When the Swedes brought up the big 24 pounders they came close to taking the place, it was only by a sortie which took out one cannon and an accident which took out another that the siege was broken. Once the big guns were gone the 'modern' army had no advantage (of course the Poles insist it was the Black Madonna who saved them).

Malbork did endure also many sieges during the 13 Years war in the mid-15th Century - during the same period when French and Burgundian cannon were so famously knocking down dozens of fortifications in short order in France and the Savoy. In Prussia, the Bohemian condottiere Ulrich Czerwonka (aka Oldrzych) was fighting for the Teutonic Order in the early part of the war, and participated in the capture of Marienburg (the town), Dirschau, and Eylau in 1455. But the Order had serious cash flow problems just then and was unable to pay their mercenaries, so they ended up giving them these towns in lieu of pay. Oldrzych immediately arranged to sell them to the only available buyer, the Prussian Confederation and the Poles, and in gratitude King Casimir IV made him Castelan of Malbork in 1457 during a personal visit. But unfortunately for Oldrzych he didn't get to bask in his newly elevated status as a Lord for very long, since the Ordensstaat's own mighty condottieri captain Bernard Von Zinnenburg (aka Bernard Zomborsky) captured the town of Marienburg (with the collusion of the mayor) later that same year. In spite of this Oldrzych, along with the resourceful Prussian Confederation officer and former Teutonic Knight Johannes von Baysen, held out in the castle for 3 more years, resisting two full-fledged assaults in 1457 and 1459. until the town was finally relieved in 1460.

It is also worth noting that 160 years later during the Deluge Karl Gustav did not storm nearby Danzig / Gdansk, a far bigger prize than derelict Malbork at that time. Danzig was very much in the economic mainstream and had famously endured a siege by Stephen Bathory and ten thousand Polish, Hungarian and Vlach troops in 1577. The Swedes attempted to blockade Gdansk during the 30 Years War in 1626, but the Prussians an Poles smashed the Swedish fleet in a battle off Glettkau on Nov. 28th 1627. In 1629 and 1630 a series of treaties established Danzig's 'neutrality' in the war, though Sweden managed to impose a partial fee on the customs tariff on Danzig trade until 1635... this alone provided half of Swedens revenues in that 5 year period! There is no doubt the Swedes would have loved to have captured it but it simply wasn't possible. In this place, defense trumped offense even with the 'modern' army. Karl Gustav's army arrived outside the town walls in 1655 during The Deluge, but neglected to even attempt a siege. Once again they tried a blockade but a Dutch fleet arrived in 1656 and broke the siege, since the Danzig trade was so important to them.

Gdansk did have the updated trace-itallienne style defenses of course by the mid 17th Century (they wisely modernized again between 1650-1655). But even more importantly they had a large garrison and plenty of guns - because they had a lot of money and knew it was in their own self interest to defend themselves.

J

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Timo Nieminen

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 1:16 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 1:16 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: | | Daniel Staberg wrote: | Jean,

Malbork/Marienburg is a poor example as it never resisted a "modern" attack in it's original medieval shape, indeed it faced little or no hostile action for 160 years after being taken over by the Poles in 1466. |

Yes but it all depends on what you mean by 'modern' Malbork faced 6 sieges (successfully) from well equipped armies between 1410-1466. This is a (19th Century) depiction of the Polish shooting at Malbork in the 1410 siege: |

The 1410 siege wasn't by what I'd call a well-equipped army. Jogaila didn't have his siege artillery with him (he used locally acquired cannon and catapults), didn't have enough men to assault.

Is Grunwald/Tannenburg (and the other stuff, like the following siege of Marienburg) Medieval or Renaissance/Early Modern? Before it is Medieval, and not long after it is post-Medieval. Not that the changes in warfare in the region were driven so much by technology as by social factors: after Lithuania Christianised, you don't raid with intent to kill civilians, burn villages, etc. to cause enough pain for the population so that they convert to make you stop. When the enemy changes from pagan Prussians and Samogitians to Poland/Lithuania (from Golden Horde to Moscow, too,depending on the area we include), war changes.

"In addition to being efficient, all pole arms were quite nice to look at." - Cherney Berg, A hideous history of weapons, Collier 1963.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 1:28 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 1:28 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Whereas the Medieval period tends to be some what vague in it's beginning, I always thought that there was a consensus that the Early Modern period is designated as starting in 1500 or 1520...?

The 1410 siege may not have been the best equipped compared to the size of the army, but they certainly had cannon... and it was a big army. And the Teutonic Order had a very small garrison left at that point. The series of sieges during the 13 Years War in 1454-66 were much better equipped with more modern cannon (and firearms) including the use of corned powder and lead shot.

| Quote: | | When the enemy changes from pagan Prussians and Samogitians to Poland/Lithuania (from Golden Horde to Moscow, too,depending on the area we include), war changes. |

Anything to do with the Tartars tended to be harsher on both sides very generally speaking, but the fighting between the Poles / Prussians / Lithuanians vs. Moscow if anything got nastier as Moscow's power and independence grew. They got along a lot better of course with the independent Rus City-States like Novgorod though there were still nasty fights with them too - gradually they came to de-facto truce and Veliky Novgorod was linked to the Hanse until Moscow took them over in 1478. With the Muscovites such harmony was very rare. The Livonian Wars (1558-1583) during the reign of Ivan IV 'Groznyi' were characterized by widespread prisoner massacres, town-massacres, wholesale civilian slaughters, and cannibalism, among other horrors. It was something of a pre-cursor to the 30 Years War in that respect.

The Teutonic Order never really did accept the Lithuanian conversion (with some reason), which went as far back as 1387 at least in theory (and according to Polish lawyers)... the perhaps un-pragmatic refusal of the Teutonic Order to accept the Lithuanian conversion and their inability to control pagan Samogitia was in fact what led directly to their shattering at Grunwald and the back of their Order being broken.

But even well before all that, during the nastiest part of the Baltic Crusading era, according to the Chronicles of Henry of Livonia the Order was exchanging hostages and prisoners with the Lithuanians in some cases, and this continued into the 14th Century on both sides such as the incident I mentioned upthread. It all depended strongly on economic factors and politics, and the realistic balance of power. The Estonians were defeated and treated very cruelly, the Lithuanians always had German prisoners to exchange so they needed to be treated more delicately, and by the 14th Century had German populated trading cities of their own and strong trade links with the Latin world through the Hansa, which meant powerful money-interests who sought peace (which is another important reason the Poles eventually merged with them).

I think when you compare the "relatively" harmonious, albeit still often violent, relationships in the Baltic with Veliky Novgorod, the independent Russian city-state / republic, vs. the typically extremely harsh and ruthless interactions with (also Russian) Moscow, you can see that the latter was by the late Medieval period becoming an Early Modern style autocratic, centralized State. When Moscow achieved full independence from the Mongols under Ivan IV ('Ivan the Terrible') they had become a modern State in the sense of the extreme centralization of power and authority in one man, the existence of State Police and intelligence networks, a tightly regulated economy and so on. Whereas their chief rival Poland was about as decentralized and Medieval as you can get, with 5 or 6 different religious and ethnic groups (the Poles, the German burghers, the Ukranian cossacks, the Lithuanians, even the lipka Tartars) an intentionally weak king, and multiple centers of power dominated by the small gentry in the szlachta. Both Russian city-states had the same cultural / religious (Greek vs. Latin church) barriers with the Latin West, both had the same inherent rivalries and conflicts as well as common trade-interests (and military interests against the Turks and Tartars), but it was against more 'modern' Moscow that war escalated so dramatically in scale and it's violence, and lasting peace seemed to be impossible.

J

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

Daniel Staberg

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 3:40 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 3:40 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: |

It is also worth noting that 160 years later during the Deluge Karl Gustav did not storm nearby Danzig / Gdansk, a far bigger prize than derelict Malbork at that time. Danzig was very much in the economic mainstream and had famously endured a siege by Stephen Bathory and ten thousand Polish, Hungarian and Vlach troops in 1577. The Swedes attempted to blockade Gdansk during the 30 Years War in 1626, but the Prussians an Poles smashed the Swedish fleet in a battle off Glettkau on Nov. 28th 1627. In 1629 and 1630 a series of treaties established Danzig's 'neutrality' in the war, though Sweden managed to impose a partial fee on the customs tariff on Danzig trade until 1635... this alone provided half of Swedens revenues in that 5 year period! |

The Swedish blockade had nothing to do with the 30-years war as Sweden did not enter that conflict until 1630 (apart from aiding the defence of Stralsund in 1628). Sweden and Poland-Lithuania had been at war since 1600, the 1626-1629 campaigns in Polish Prussia was merly the latest phase in that long conflict. The battle of Oliwa 1627 was not even remotely a smashing defeat for the Swedes, a total of 2 ships were lost which left the other 96,4% of the fleet to carry on it's duties the next year.

The Swedish blockade was a seasonal affair as the ships had to retire to safe ports before the onset of the harsh Baltic winter. The battle of Oliwa took place after the blockade had been lifted and the Polish victory did not in any way prevent the Swedes from reestablish the blockade in 1628. The Swedish blockade of Danzig had limited objectives, the first was to prevent the Polish navy from interfering with Swedish trade and troop transports, the other was to enforce a Swedish toll on the Danzig trade. So even with the Swedish blockade in place trade did flow, the merchants just had to pay an extra toll.

Danzig did not provide "half of Swedens revenues", the total income from Prussia and the tolls collected on the Vistula trade was roughly 1/3 of the Crown's revenues in 1630-1635. An important source of income to be sure but it's importance has been exaggerated due to a couple of misunderstood statements by Axel Oxenstierna.

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: | | There is no doubt the Swedes would have loved to have captured it but it simply wasn't possible. In this place, defense trumped offense even with the 'modern' army. Karl Gustav's army arrived outside the town walls in 1655 during The Deluge, but neglected to even attempt a siege. Once again they tried a blockade but a Dutch fleet arrived in 1656 and broke the siege, since the Danzig trade was so important to them. |

Neither Karl Gustav nor his army was outside the walls of Danzig in 1655, he was way to busy advancing deep into central and southern Poland. Nor is his presence there mentioned anywhere on the wiki page, perhaps you meant to link to another web page?

Nor was there any siege in 1656 for the Dutch to break, the Dutch fleet did not fight the Swedes at all and sailed back to the Netherlands after the treaty of Elbing was signed.

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: |

Gdansk did have the updated trace-itallienne style defenses of course by the mid 17th Century (they wisely modernized again between 1650-1655). But even more importantly they had a large garrison and plenty of guns - because they had a lot of money and knew it was in their own self interest to defend themselves.

|

Without the modern defences the guns & men would have been of limited value if the Swedes had mustered the resources for a siege. It was the combination of all 3 that made Danzing the strongest fortress in Northern Europe at the time. Just what the outcome of a siege would have been is hard to say given that Danzig's defences were never seriously tested. In 1626-1629 capturing the city was never part of the Swedish strategy, in 1655 Danzig probably was a target but Karl Gustav changed his plans and instead advanced deep into Poland.

"There is nothing more hazardous than to venture a battle. One can lose it

by a thousand unforseen circumstances, even when one has thorougly taken all

precautions that the most perfect military skill allows for."

-Fieldmarshal Lennart Torstensson.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 8:54 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 8:54 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Daniel I'm not sure where you are getting your information, but it doesn't match my sources.

| Daniel Staberg wrote: | | Neither Karl Gustav nor his army was outside the walls of Danzig in 1655, he was way to busy advancing deep into central and southern Poland. Nor is his presence there mentioned anywhere on the wiki page, perhaps you meant to link to another web page? |

I linked to the wiki on the Livonian War just for the benefit of anyone reading the thread who was not familiar with it, I wasn't trying to quote a reference. But since you ask I can quickly google some online articles which refer to the initial phases of the invasion, pertinent to my point. For example 'history of War.org' makes this statement:

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/wars_northern1655.html

| Quote: | | Charles’s initial aim was the conquest of Royal Prussia (west Prussia, part of the kingdom of Poland and including the important city of Danzig). In the summer of 1655 he launched a two pronged invasion of Royal Prussia. One army under Magnus de la Gardie was to attack from the Swedish possessions in Livonia, while the main army, at first under Arvid Wittenberg, would invade from Swedish Pomerania. Charles himself followed close behind with reinforcements. |

and this one

| Quote: | | Charles spent the last months of 1655 attempting to conquer Royal Prussia, his original target. Here he was faced with a number of well defended cities, chief amongst them Danzig, and with a potentially dangerous enemy in Frederick William, elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia. On 12 November, under pressure from John Casimir, the Royal Prussian nobility signed the treaty of Rinsk, in which Frederick William agreed to garrison the Prussian towns. Danzig, Elbing and Thorn refused to accept the garrisons, but in any case the agreement did not last long. With the apparent collapse of resistance in the rest of Poland, Elbing and Thorn surrendered to Charles. Frederick William withdrew his garrisons from the rest, and then on 17 January 1656 signed the Treaty of Königsberg with Charles, in which he switched his allegiance and that of Ducal Prussia from Poland to Sweden. Soon only Danzig was holding out against Charles. |

and this one

| Quote: | | Charles’s situation in the rest of Poland quickly deteriorated. His small garrisons were vulnerable the moment a sizable Polish army was in the field, and by the spring of 1656 John Casimir had close to 30,000 men at his disposal. Charles was forced to abandon his attempts to capture Danzig and return south to deal with the new threat. |

Which seem to imply that not only the Swedish Army, but Carl himself were directly involved with Danzig and hoping to capture it. See also:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Danzig_...%931660%29

and

http://www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/danzig15571660.html

The wiki on the Northern War further states that when the combined Dutch / Danziger forces lifted the Swedish blockade in 1457, Carl Gustav himself was only 55 miles away at Elbing. They list their source as Frost, Robert I (2004). After the Deluge. Poland-Lithuania and the Second Northern War, 1655-1660. Cambridge Studies in Early Modern History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54402-5.

| Daniel Staberg wrote: | | Nor was there any siege in 1656 for the Dutch to break, the Dutch fleet did not fight the Swedes at all and sailed back to the Netherlands after the treaty of Elbing was signed. |

The people at militaryhistory.org seem confused on this point too then, because they said:

| Quote: | | The international position now began to turn in Poland’s favour. Swedish success worried their neighbours and rivals. The Dutch responded by sending a fleet to break to blockade of Danzig. |

Specifically what the Dutch fleet did was re-open the Danzig harbor, from what I understand. The wiki on the Treaty of Elbing also mentions the Dutch 'intervention'

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Elbing

The wiki also agree with my assertion as to the reason for the Dutch intervention here:

| Quote: | | The Dutch Republic heavily relied on grain imports from the Baltic Sea region, much of it was bought from Royal Prussia's chief city Danzig (Gdansk). |

and goes on to mention the exact number of the Dutch land forces, 'forty-two Dutch and nine Danish vessels ...carrying 10,000 soldiers and 2,000 guns.'

| Daniel Staberg wrote: |

Without the modern defences the guns & men would have been of limited value if the Swedes had mustered the resources for a siege. It was the combination of all 3 that made Danzing the strongest fortress in Northern Europe at the time. Just what the outcome of a siege would have been is hard to say given that Danzig's defences were never seriously tested. In 1626-1629 capturing the city was never part of the Swedish strategy, in 1655 Danzig probably was a target but Karl Gustav changed his plans and instead advanced deep into Poland. |

See the above. If that website isn't good enough for you I can cite some real books. I think Hans Delbruck gets into this in some detail in Volume IV of his History of the Art of War.

J

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

Timo Nieminen

|

Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 10:38 pm Post subject: Posted: Fri 13 Jul, 2012 10:38 pm Post subject: |

|

|

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: | | Whereas the Medieval period tends to be some what vague in it's beginning, I always thought that there was a consensus that the Early Modern period is designated as starting in 1500 or 1520...? |

It isn't like people woke up one morning and it was not longer Medieval. It was a transition that took some time. Where one chooses the cut-off date between Medieval and post-Medieval should depend on what one is comparing - different things changed at different times - and where. 1500 is a common convention. But 1400 as the beginning of the Renaissance is also common enough.

One could play safe and compare 1300 to 1600.

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: | | The 1410 siege may not have been the best equipped compared to the size of the army, but they certainly had cannon... and it was a big army. And the Teutonic Order had a very small garrison left at that point. The series of sieges during the 13 Years War in 1454-66 were much better equipped with more modern cannon (and firearms) including the use of corned powder and lead shot. |

How large was Jogaila's force at Marienburg? He would have had about 30,000 in total after Grunwald, but surely some must have been elsewhere in Prussia, rather than at Marienburg. Still, he had enough there for it to be a major distraction. Von Plauen had his 3000 from Schwetz, plus whoever he could scrape up from anywhere.

Still, Jogaila didn't have his siege artillery with him, and what he had with him wasn't enough to make much of an impression on the walls. To little, too small.

In 1457, the Poles had the wonder weapon, money, with which they took Marienburg with rather less fighting than the Teutonic Knights hoped for.

"In addition to being efficient, all pole arms were quite nice to look at." - Cherney Berg, A hideous history of weapons, Collier 1963.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Sat 14 Jul, 2012 7:18 am Post subject: Posted: Sat 14 Jul, 2012 7:18 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Quote: | | In 1457, the Poles had the wonder weapon, money, with which they took Marienburg with rather less fighting than the Teutonic Knights hoped for. |

Yeah, though technically it was their allies the Hanseatic towns of the Prussian Confederation who had the money... the King and the military leaders of the Confederation forced a gigantic, staggering tax payment on the Prussian cities to buy those 3 towns the mercenaries were selling, which led to uprisings and probably cost the burghers everything they had in terms of liquid assets, but in exchange Casimir Jagiellon gave them permanent freedoms and trade concessions which made them rich and independent for the next 200+ years, and later on even peacefully have their own Lutheran religion within a Catholic Kingdom.

One thing about the Poles, they were very pragmatic.

J

EDIT: It's funny by coincidence, the background image on Bing today is of Gdansk / Danzig. Lovely photo.

This one gives you a real good overview of the scale of the defenses in the 17th C

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

T. Arndt

|

|

|

|

Robert Rytel

Location: Pittsburgh Joined: 23 Oct 2011

Posts: 32

|

Posted: Sat 14 Jul, 2012 5:01 pm Post subject: Posted: Sat 14 Jul, 2012 5:01 pm Post subject: |

|

|

|

When I was reading about Sir John Hawkwood and The White Company, I recall reading about pike warfare of that specific period in Italy being little more than crowded shoving matches with less casualties than in previous eras thanks to the tactics employed and the proliferation of decent armor even for lowly soldiers.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Sat 14 Jul, 2012 6:39 pm Post subject: Posted: Sat 14 Jul, 2012 6:39 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I think what both of you said was true, simultaneously, at different specific times and places throughout the period.

Armor was probably most ubiquitous from roughly 1380-1520, so I don't know whether that qualifies as Medieval.

Hawkwood was involved in some nasty incidents himself...

J

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2024 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|