Out of practical curiousity, I'm wondering, were most viking age & medieval sword fullers forged or ground in?

If forged, how was this accomplished? How would you (assuming you have practical knowledge in this skill) specifically go about forging in the fullers in a blade?

If ground (or cut) how was this accomplished?

Please give as much detail as possible.

If you are a modern day swordsmith and you forge or grind fullers, what is your process?

Thanks,

Dustin

Hey Dustin,

I've see a few designs for a fullering tool that consists of two sections of barstock welded to a c-shaped spring. You just run the blade down the tool and hammer on the top of it to create two equal fullers on either side of the blade. I seriously doubt that this is the traditional method, but it's brilliantly simple.

I've see a few designs for a fullering tool that consists of two sections of barstock welded to a c-shaped spring. You just run the blade down the tool and hammer on the top of it to create two equal fullers on either side of the blade. I seriously doubt that this is the traditional method, but it's brilliantly simple.

I can't speak specifically to viking era forging techniques, but I can speak to the principle and tradtional tools of a blacksmith that in all likelyhood is not dissimilar from that era.

The "Spring Fuller" previously described, is a single-handed contemporary variation of the top and bottom fullering tools that have been around forever. A bottom fuller is essentially a rounded off wedge that is held static in the hardie hole of an anvil. The top fuller mirrors this shape, but has an eye for a handle that is held by the smith in allignment above the bottom fuller. This configuration requires a striker (someone swinging a sledge hammer to strike the top fuller). It is up to the smith to move the work back and forth between the top and bottom fullers and to keep the two tools aligned.

In all likeleyhood an assembly like the spring fuller described could have been imagined at any point in history and I'm sure such tools existed in some form or another, though I doubt the archaelogical record can back it up as far back as the period you are inquiring about. for something as long and narrow as a sword blade, I'm sure some sort of guide must have been employed to align the striking faces and to center the fuller.

Keep in mind that a top and bottom fuller as tools are not resigned to making sword fullers. This is and has been a basic decorative and practical forging technique for the history of working iron and steel.

Cheers, Adair

The "Spring Fuller" previously described, is a single-handed contemporary variation of the top and bottom fullering tools that have been around forever. A bottom fuller is essentially a rounded off wedge that is held static in the hardie hole of an anvil. The top fuller mirrors this shape, but has an eye for a handle that is held by the smith in allignment above the bottom fuller. This configuration requires a striker (someone swinging a sledge hammer to strike the top fuller). It is up to the smith to move the work back and forth between the top and bottom fullers and to keep the two tools aligned.

In all likeleyhood an assembly like the spring fuller described could have been imagined at any point in history and I'm sure such tools existed in some form or another, though I doubt the archaelogical record can back it up as far back as the period you are inquiring about. for something as long and narrow as a sword blade, I'm sure some sort of guide must have been employed to align the striking faces and to center the fuller.

Keep in mind that a top and bottom fuller as tools are not resigned to making sword fullers. This is and has been a basic decorative and practical forging technique for the history of working iron and steel.

Cheers, Adair

I am going to speculate that they were probably ground or filed, as the industrial technologies for doing it that way tend to overlap the time frame of when fullers seem to become more common. The mining and production of grinding stones (green stone in and around England and near by regions, widely used for grain mills, grinding stone, etc.) was an established industry by the middle of the Danish definition of "viking era" (fully developed grinding stone production industry between 10th and 11th century.) We tend to lump earlier 'Migration era" swords together with what I consider the main part of the viking era, but most of these earlier era swords did not have fullers. It could just be a coincidence. I have the traditional anvil mounted bottom fuller type tool, BTW, and its not that easy to use. I would much rather attempt a good quality sword fuller through grinding than by forging with a fullering tool.

I wonder if one might not initiate the fuller and establish it's basic length and position by forging and finish it in depth and width by grinding as well as smooth out irregularities ?

With forging maybe less wasted material at a time when good iron/steel was more valuable than labour ?

I imagine that some fullers may have been done mostly by forging with grinding being just for the finishing, other cases of using both methods about equally ( Least certain about this as it might be more trouble than it's worth rather than simply grinding in fullers ? ), or going strait to grinding without any forging involved in making the fullers?

With forging maybe less wasted material at a time when good iron/steel was more valuable than labour ?

I imagine that some fullers may have been done mostly by forging with grinding being just for the finishing, other cases of using both methods about equally ( Least certain about this as it might be more trouble than it's worth rather than simply grinding in fullers ? ), or going strait to grinding without any forging involved in making the fullers?

I assumed that finish grinding was a given. The argument for conservation of material by forging is a strong one. Not to mention conservation of abrasives.

Even today, the blacksmiths with the most talent are the ones who don't spend much time grinding. Forging is fast compared to grinding and much more enjoyable.

As far as the difficulty of forging a fullered groove top and bottom: an assistant on both ends of the blade, a striker and a smith with a top tool and the job becomes quite controllable.

Those images of the rough forged fullers are wonderful.

Just a reminder, I am speculating based on a knowledge of blacksmithing techniques from the last couple centuries.

Cheers, Adair

Even today, the blacksmiths with the most talent are the ones who don't spend much time grinding. Forging is fast compared to grinding and much more enjoyable.

As far as the difficulty of forging a fullered groove top and bottom: an assistant on both ends of the blade, a striker and a smith with a top tool and the job becomes quite controllable.

Those images of the rough forged fullers are wonderful.

Just a reminder, I am speculating based on a knowledge of blacksmithing techniques from the last couple centuries.

Cheers, Adair

| M. Adair Orr wrote: |

|

...The argument for conservation of material by forging is a strong one. Not to mention conservation of abrasives... . |

This is an important point... With the relative abundance and low cost of steel today it is not that shocking to grind away a high percentage of your raw material. I suspect that the medieval sword smith would be horrified to see one of his apprentices grinding away such a high percentage. Forging would conserve these valuable natural resources.

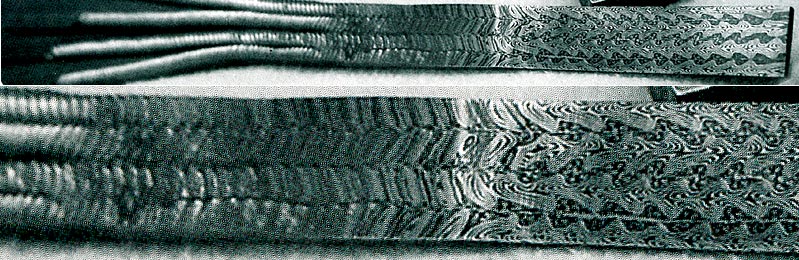

That being said, there is evidence that fullers were ground. Patternwelded cores of sword blades allows some conjecture on wether the fuller was forged or ground. If a twisted billet is forged it will collapse and the outer whirls will appear in the etched surface as diagonal lines, usually in a herringbone like configuration. However, if these same billets are ground, the stone will cut through the outer whirls and deep into the interior of these twisted billets revealing curved eddie like patterns. So forged blades will have a more herringbone pattern and ground blades will have curved "blood eddie" surface patterns. (This can be seen in the attachment from Manfred Sachse excellent work on Damascus Steel. Notice that with forging flat the layers appear straight but with grinding they appear as sinuous curves.)

In a landmark article by Janet Lang and Barry Ager "Swords of the Anglo-Saxon and Viking periods in the British Museum: A Radiographic Study," this is one of the important conclusion:

"Many Continental patterns have curving patterns, resulting from grinding away the surface. In the British Museum such a pattern is only present on part of one sword, from Crundale Down. It seems likely that most of the British Museum swords were finished by hammering rather than grinding and are therefore probably the product of a local technological tradition which has developed differently from that on the Continent."

Hope this helps.

take care

ks

From "Damascus Steel" by Manfred Sachse

Forging fullers using a top and bottom spring tool takes some practice but is not terribly difficult. Jigs can be used to help keep things aligned, the same as for grinding them. Honestly grinding them freehand is about as difficult (for me) as forging them freehand, and as mentioned forged fullers will almost invariably be ground or scraped smooth afterwards, at least in modern context. The difficulty involved in either method is mostly a matter of practice, experience, and tooling. This is one area where I have found the adage "an hour at the anvil is worth 2 at the grinder" to be untrue, however. To forge them straight is time consuming.

I'd say both forging (and finish grinding) and grinding were used. Various patternwelded swords show that nearly half of the billets were ground away. The shapes of fullers also differ greatly. Some fullers are fairly narrow and deep, while others are wide and very shallow. Narrow, deep fullers lend themselves more to being forged. Wide, shallow fullers are more likely ground. It makes no sense forging in a 0.5 mm fuller if you have to grind away >1mm of metal to clean up the blade after forging. On the other hand, there probably was a lot of cold working involved. So shallow fullers could also have been hammered in cold.

| Kirk Lee Spencer wrote: |

| Hope this helps.

take care ks |

Thank you, this is very interesting.

How were those shallow, broad fullers ground? How would you grind one now?

I find it way easier *and faster* to forge them.

With the device stated before, or with a round hammer, on a round surface, if I want to make a broader fuller.

After that, I polish (or grind, if necessary) it with an angle grinder and flap discs.

These are useful too when making convex edges.

Grinding or hammering also depends on if you are working on damascus or not.

Greetings

Andrés.-

With the device stated before, or with a round hammer, on a round surface, if I want to make a broader fuller.

After that, I polish (or grind, if necessary) it with an angle grinder and flap discs.

These are useful too when making convex edges.

Grinding or hammering also depends on if you are working on damascus or not.

Greetings

Andrés.-

| Dustin R. Reagan wrote: |

| How were those shallow, broad fullers ground? |

Either with a scraper, or with a grinding wheel. I looked at the measurements, and it would have taken a wheel of 40cm diameter to create the width and depth on these shallow fullers.

| Quote: |

| How would you grind one now? |

This is an example I have posted several times on this forum when questions regarding forging and grinding has come up.

Grinding was part of the manufacture of blades and has always been.

Fullers can be partly forged and then finished with grinding, or more or less completely scraped or ground.

This example is a sword found in Fullerö. It shows clearly the piled structure of the edge. The way the layers become more tight towards the edge show that grinding was used to shape the cross section to a rather large extent. The fullers are ground (perhaps mostly of completely) and a wheel (or a scraper/chisel) was used that had a diameter of around 15- 20 cm. The pattern in the fullers are cut away almost down to the middle of the twisted bars, but there is not distortion from cutting/chiseling the bars in two to open up the pattern.

I do not think that iron was so valuable that this was cause to avoid grinding. It was rather a case of what method gave the desired result, balancing work time and desired effect with the patterns. Some patterns need more grinding, other patterns cannot be ground so much.

Pattern welding uses up quite a lot of material in the process, lost as scale. If preservation of material was of high concern, we would not see such dedicated and advanced patterns on blades. I think more material might have been lost in the forging during welding, than in the grinding in many cases.

Blades were forged pretty close to shape, but as this blade from Fullerö shows, they were not shy leaving a forged edge thickness of around 2-3 mm or so (at a guess). The rest of the shape was ground and filed to shape before and after heat treat. The Fullerö sword also clearly shows that surface finish was very good. Well defined and probably with a pretty high polish. They were as skilled in grinding as they were in forging.

Attachment: 46.75 KB

Attachment: 46.75 KB

Grinding was part of the manufacture of blades and has always been.

Fullers can be partly forged and then finished with grinding, or more or less completely scraped or ground.

This example is a sword found in Fullerö. It shows clearly the piled structure of the edge. The way the layers become more tight towards the edge show that grinding was used to shape the cross section to a rather large extent. The fullers are ground (perhaps mostly of completely) and a wheel (or a scraper/chisel) was used that had a diameter of around 15- 20 cm. The pattern in the fullers are cut away almost down to the middle of the twisted bars, but there is not distortion from cutting/chiseling the bars in two to open up the pattern.

I do not think that iron was so valuable that this was cause to avoid grinding. It was rather a case of what method gave the desired result, balancing work time and desired effect with the patterns. Some patterns need more grinding, other patterns cannot be ground so much.

Pattern welding uses up quite a lot of material in the process, lost as scale. If preservation of material was of high concern, we would not see such dedicated and advanced patterns on blades. I think more material might have been lost in the forging during welding, than in the grinding in many cases.

Blades were forged pretty close to shape, but as this blade from Fullerö shows, they were not shy leaving a forged edge thickness of around 2-3 mm or so (at a guess). The rest of the shape was ground and filed to shape before and after heat treat. The Fullerö sword also clearly shows that surface finish was very good. Well defined and probably with a pretty high polish. They were as skilled in grinding as they were in forging.

More great info. Several of you have referred to a tools called a scraper. Can you give me more info on this? What do they look like and how do they function? How would you use one to cut in a fuller?

Thanks,

Dustin

Thanks,

Dustin

The ones I have seen are similar in form to a spokeshave, with a carbide or tool steel cutting bit. I have no idea if ones used historically looked anything like this.

| Justin King wrote: |

| The ones I have seen are similar in form to a spokeshave, with a carbide or tool steel cutting bit. I have no idea if ones used historically looked anything like this. |

I had the same thought: I would have liked to post that Psalter image.

There is no telling if it is a scraper or a polishing tool, however. The sword that is being worked on is fully mounted: it has a complete hilt. This might just be artistic license, or it might mean that the swords in the image are being seen to before battle, getting a sharpening and polish, rather than being made.

The tool looks like a small axe with handles protruding on both ends. The blade is on a low bench and is worked on with both hands and full body weight of the cutler.

There is no telling if it is a scraper or a polishing tool, however. The sword that is being worked on is fully mounted: it has a complete hilt. This might just be artistic license, or it might mean that the swords in the image are being seen to before battle, getting a sharpening and polish, rather than being made.

The tool looks like a small axe with handles protruding on both ends. The blade is on a low bench and is worked on with both hands and full body weight of the cutler.

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| I had the same thought: I would have liked to post that Psalter image.

There is no telling if it is a scraper or a polishing tool, however. The sword that is being worked on is fully mounted: it has a complete hilt. This might just be artistic license, or it might mean that the swords in the image are being seen to before battle, getting a sharpening and polish, rather than being made. |

Page 1 of 2

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum