| Author |

Message |

|

Michael Pikula

Industry Professional

Location: Madison, WI Joined: 07 Jun 2008

Posts: 411

|

Posted: Sun 30 Nov, 2008 12:19 am Post subject: Pattern development for the Illerup Adal finds Posted: Sun 30 Nov, 2008 12:19 am Post subject: Pattern development for the Illerup Adal finds |

|

|

Hello everyone, I was wondering if anyone knows how a few of the patterns that were used in the late Roman blades that were part of the Illerup Adal find where developed using low technology techniques.

I have been looking at the "knot" pattern that was used in the diamond opening that are framed by a "basket weave" and I can't come up with what would be an efficient way or creating this without wasting time, material, and the blade grinders time just because one weld didn't take. Even with the aid of modern tools this seems like a massive undertaking but if you were to be a smith from the times of old and had orders to fill for men going to war I don't see that taking that kind of a risk was worth the effort...

Secondly, everything that the Vikings did, which had a lot to do with twisting, had a purpose in the process of making the sword. In the case of twisting it was to test welds and break off scale, what would be the purpose of creating the complex mosaic patterns in the blades that the Romans did? I was thinking that some of it could have been simply to show off their skills, but there are so many finds with these examples that wouldn't it logically make sense that it was a common practice in forging the blade?

Mainly I am looking to strike up a conversation that has to do with these wonderful blades. I only have volume 11 and 12 right now and am on the hunt for more texts from this find and any others that feature the complex pattern welded, but money is tight so I have to be happy with what I have.

Comments and ideas are very welcome!

Cheers,

btw I had this post in the Maker forum for about half an hour because I posted it in the wrong spot, my bad!

|

|

|

|

Kirk Lee Spencer

|

Posted: Mon 01 Dec, 2008 1:10 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 01 Dec, 2008 1:10 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Hi Michael...

First off let me say that you are doing some really amazing pattern-welding! It is good to have you here and I look forward to seeing more of your forge work in the future.

It is interesting that you bring up the subject of the very fine (and diverse) pattern-welding in the bog finds-- I was just thinking of this the other day. I have my Illerup Adal Vol. 11 & 12 on order. So when I get them I will certainly have more to add. I do have some 19th century drawings from Nydam Mosefund by Conrad Engelhardt and a couple of photographs. I have attached them to this post. Let me know if this is what you are talking about.

I'm not sure that I have ever seen anyone try to replicate these late Roman patterns. I would really like to hear if anyone has tried a little experimental archeology in the forge.

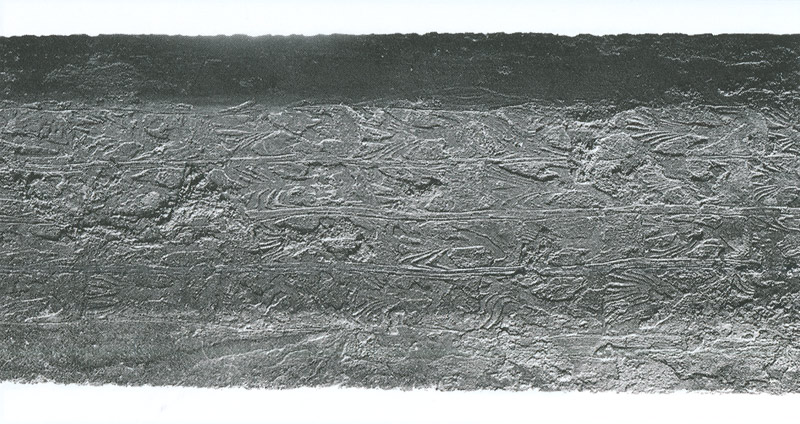

The layers appear to be very fine, like wires rather than billets. It reminds me of the earlier celtic swords that show a piled structure seen as welded wires, usually running down the length of the blade forming the core (see attachment). I have not heard of any torsion (twisting) of these wires in the Celtic finds (Although I did see a drawing of a Celtic La Tene sword with torsion in the tang). The earliest torsion pattern-welding I have seen were in Roman pugio daggers which I assume are probably 1st century A.D. at the earliest (see attachment).

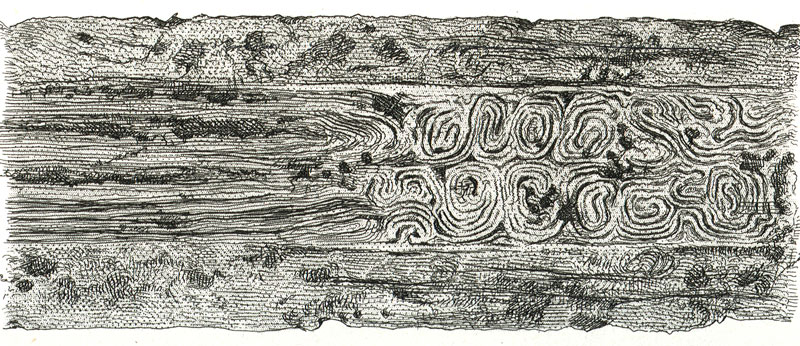

Of course in the bog finds there are also fine examples of torsion patterns, however there are also many blades that have wires in a piled structure running down the length of the blade as in the Celtic forms, however there is more variation from solid to thin wire bundles across the blade core (see attachment).

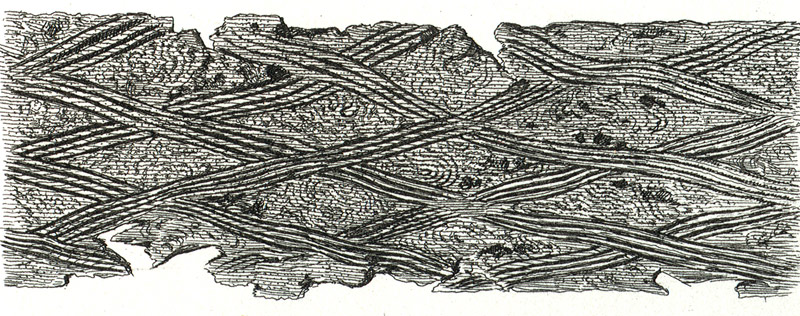

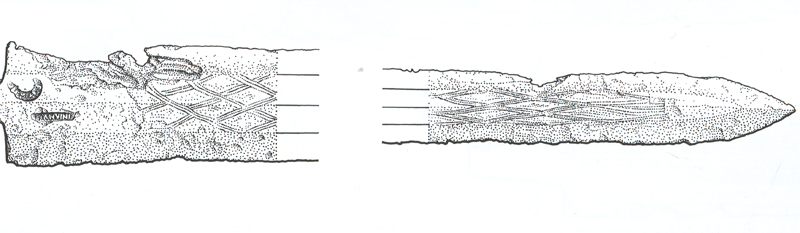

It may be that the knotted patterns you are referring to were experiments based upon the success with torsion (or leading up to it) where the wires were coiled (something the Celts really liked in their decoration) or braided (generating a knotted pattern that would become popular throughout the Middle Ages). The coiled or braided wires were then hammer welded together at welding temperature as a core (or into the surface of an iron core)

I suspect, as you say, there were many welds that didn't take. This might very well explain why this coiled form did not persist. And I had the thought that the cold shuts and weak welds, might even explain why the cross hatching of iron was inlayed into the surface of the blade (see attachments). It may have acted to cover some of the cold shuts and weak welds and add integrity to the structure of the blade. (It would be interesting to see a detailed xray of the blade with the cross-hatched iron inlay and see it there is any evidence of weakness below the inlay.) There have been several pattern welded blades that show patches and even rivets to hold the blade together.

Great question and I hope we can get some more discussion going. I would really like to know more about these beautiful blades...

take care

ks

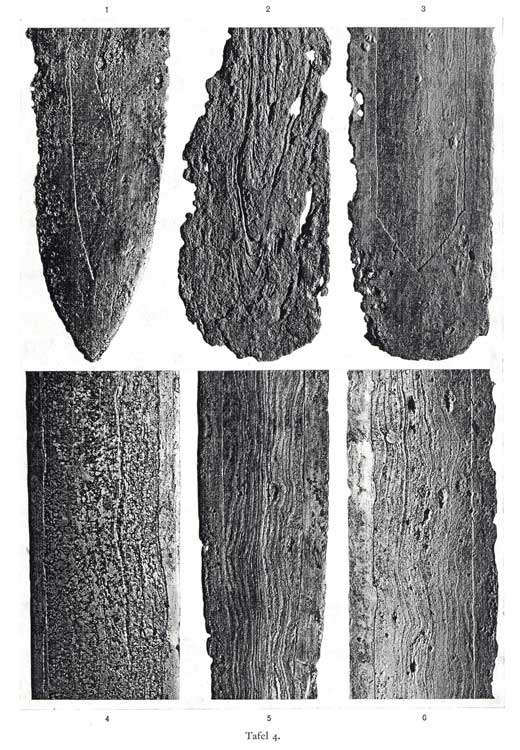

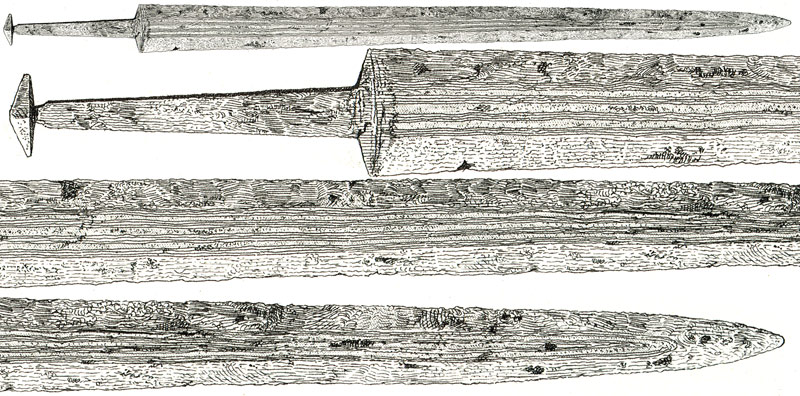

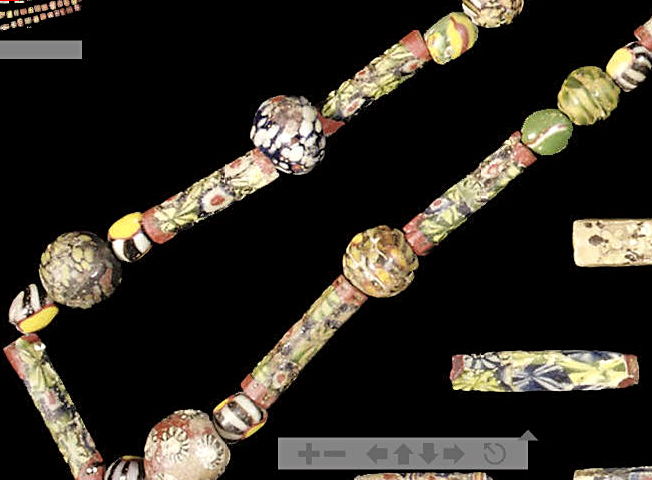

Attachment: 91.22 KB Attachment: 91.22 KB

Celtic LaTene blades with piled core

Attachment: 61.64 KB Attachment: 61.64 KB

Pugio with tortion pattern welding Image from Roman Legions Site

Attachment: 140.34 KB Attachment: 140.34 KB

Late Roman Piled Core from Nydam Bog Denmark. Length 80cm, Blade Lenth 67cm Blade Width 48mm drawing from "Nydam Mosefund" by Conrad Engelhardt

Attachment: 141.68 KB Attachment: 141.68 KB

Pattern-welded core from Nydam Bog preserved in National Museum of Denmark. Image from "Swords of the Viking Age" by Ian Peirce

Attachment: 149.27 KB Attachment: 149.27 KB

Diamond shape Iron Inlay in pattern welded core from Nydam Bog Denmark. Drawing from "Nydam Mosefund" by Conrad Engelhardt. Shows the pattern under the inlay looks like spirals wire

Attachment: 147.27 KB Attachment: 147.27 KB

Another Engelhart drawing of a sword from Nydam Bog which shows both a piled leading into a coiled like structure. Image from "Nydam Mosefund" by Conrad Engelhardt

Attachment: 99 KB Attachment: 99 KB

Another pattern welded blade with coiled like pattern although I think I see three separate billets. Preserved in LandesMuseum Zurich Switzerland

Two swords

Lit in Eden’s flame

One of iron and one of ink

To place within a bloody hand

One of God or one of man

Our souls to one of

Two eternities

|

|

|

|

|

Michael Pikula

Industry Professional

Location: Madison, WI Joined: 07 Jun 2008

Posts: 411

|

Posted: Tue 02 Dec, 2008 10:23 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 02 Dec, 2008 10:23 am Post subject: |

|

|

Hi Kirk, you bring up some very interesting points and I haven't given much thought to the piled structure because somehow it hasn't caught my eye as too appealing, but it is interesting and I will be looking at it in more detail. I have some scrap billet section lying around and I'll see what I can do about manipulating them or using them to try to create something of that aesthetic when I get some time.

We should defiantly talk more when you have a chance to look over 11 &12 when you get them, the pattern that I am talking about are very exact and extremely intentional. I am almost tempted to say that maybe they used their little scrap sections and forged them into really small sections, possibly like wire, then inlayed a set opening that was either carved out, or possibly even a basic form was stamped into the sections desired. Then cleaned up/added final detail with a chisel and hammering in the detailed work. I am also wondering if they may have used some of the filing from the forming of the blade inside of these openings. I have used the L6 that I ground out with a 36 grit belt to fill the voids of a billet I made/is in progress of making that used a whole bunch of scrap pieces of pattern weld I had around the shop, just as an experiment. The first weld and drawing are showing some very promising results...

Two problems with this line of thinking are if this was the case you would more then likely have to work very small sections of the blade at a time so as not to displace the forms before you got to weld them. Secondly if you do two sides and are only working small sections are you over working the steel in those sections? I would imagine you would want to forge the blade to shape as well so there you are adding more time hot, and if it isn't worked at the right temperature I can see failure. Secondly depending on if the fullers were partially forged or ground would mean that the depth of the inlay might have to be pretty deep and from what I have seen so far there is no indication of grinding through the patterns.

I figure that the "palm tree" mosaic that they did and the basket weave would not be a problem since it would be... easier... to get a good depth to the pattern. But I haven't had time to play with this to try to figure it out, or at least get some further insight.

Looking to stimulate the brain then take it to the forge instead of jumping in and hoping for the best.

|

|

|

|

Kirk Lee Spencer

|

Posted: Mon 15 Dec, 2008 11:37 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Dec, 2008 11:37 am Post subject: |

|

|

Hi Michael...

Well... I received Vols. 11 & 12 of the Illerup Adal series. It is certainly an important monograph. Well worth the money. It is going to take me some time to process it all. The images in these volumes on the diamond gridwork and palm tree and knotted mosaic forms have made any simple explanation difficult to imagine. You are certainly right, they are very intensional and well done.

I recognize a similarity between the palm tree forms and somewhat similar patterns I have seen in Roman glass beads from the same time period. So if someone knows how the glass beads were made, that might go along way in possibly understanding how these billets came together. Instead of molten glass they were working with iron at welding temperatures.

I don't think that they were working the blade in sections for the same reasons you mentioned. So many times reheating the whole blade to welding temperature would eventually begin to burn the iron.

It may be the reason it looks like mosaic damascus is because it is. I have a friend who has been experimenting with some mosaic damascus. He places fragments and wires in a can in a particular pattern. He has two curved dies that he has made for his press which pushes on the can like a vise with curved jaws to weld all the wires together at weld temperature. He then cuts it like cookie dough to weld into other projects.

I was wondering if it would be possible to do a similar thing in long straight sections (you would not need special dies). Rather than a can it would be two vertical plates spaced about half inch apart with some kind of bottom. Iron in thins sheets and wires could be placed between these two plates in bundels to create the palm tree pattern. The intervening spaces could be filled with filings from the shop floor. The whole would be welded together as a solid bar. This thick bar could then be cut into thin sections and layed side by side and welded together along the edges to form the blade core. It is interesting to me that the palm tree designs usually have piled layers (thin straight layers) between the mosaics. If they were made in the way just described, then these piled layers between may be the plates that were used confine the mosaic elements as they are packed into place.

One way to test this idea is to look at the palm tree pattern which all vary slightly form one to the next and see if there is a similar progression similar palm tree designs in some of the bars. This would be expected if they were cut from the same large mosaic bar, the sequence in the original would be replicated in each section cut from it.

One thing is clear from the illustrations in the monograph... the diamond gridwork, if it is some kind of inlay, as I have heard, has been done before the blade was forged to shape because it shows elongation near the tip of the blade.

Hope all this make sense.

take care

ks

Attachment: 143.05 KB Attachment: 143.05 KB

Attachment: 146.19 KB Attachment: 146.19 KB

Illerup Adal "Die Schwerter." vol. 11 & 12

Attachment: 141.58 KB Attachment: 141.58 KB

Illerup Adal "Die Schwerter." vol. 11 & 12

Attachment: 143.28 KB Attachment: 143.28 KB

Illerup Adal "Die Schwerter." vol. 11 & 12

Attachment: 105.24 KB Attachment: 105.24 KB

Illerup Adal "Die Schwerter." vol. 11 & 12

Two swords

Lit in Eden’s flame

One of iron and one of ink

To place within a bloody hand

One of God or one of man

Our souls to one of

Two eternities

|

|

|

|

|

Michael Pikula

Industry Professional

Location: Madison, WI Joined: 07 Jun 2008

Posts: 411

|

Posted: Mon 15 Dec, 2008 4:34 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Dec, 2008 4:34 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Happy to hear you got 11&12! There sure is a wealth of information in there. I should have learned German so that I could understand the text though.

I was thinking about the Palm mosaic and I agree that making some kind of a bar which could have been cut into tiles and the tiles used to make up the patterning on the blade. I was thinking how the tiles could have been held in place using a low tech method... Sometimes you can see a very faint line at the top of the palm which would correspond to the tile theory. Do we know if the patterning on the front and back are symmetrical? This could offer insight as to the technique that was used...

I am still at a loss for the knot though... It has a "flow" to the lines but I have no idea how to translate it to steel.

I don't know why I am interested so much in the traditional technique say for to understand how the minds of our predecessors worked. It must have made sense and been a cut and paste operation for them. I kind of have a full plate right now with work, but I will be getting some modeling clay in the near future to play with different ideas that come up.

Man, that knot pattern....

|

|

|

|

|

Gary Teuscher

|

Posted: Mon 15 Dec, 2008 4:42 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 15 Dec, 2008 4:42 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Since you guys seem pretty knowledgeable in pattern welding, let me ask a question

I've heard 2 schools of thought on pattern welding. One is it was done to produce a higher quality blade, even though it was less efficient time wise.

The other was that it was necessitated by having small amounts of bog iron to work with - the quality was not any better, but it required a lot more work, but for some iron poor cultures this was their only option.

I would assume there are some truths to both.

|

|

|

|

|

Jeroen Zuiderwijk

Industry Professional

|

Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 3:28 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 3:28 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Gary Teuscher wrote: | Since you guys seem pretty knowledgeable in pattern welding, let me ask a question

I've heard 2 schools of thought on pattern welding. One is it was done to produce a higher quality blade, even though it was less efficient time wise.

The other was that it was necessitated by having small amounts of bog iron to work with - the quality was not any better, but it required a lot more work, but for some iron poor cultures this was their only option. |

I'm not following the latter. Why would you go patternwelding if you have little iron available?

The main reason for patternwelding (other then simple piled constructions) is because it's pretty. The more complex the pattern, the more pimped out your sword. And particularly in the early days there was a lot of showing off by more complex and unique patterns.

As for the work involved, remind that any sword had a pretty significant amount of folding and welding involved. The cheapest, most simple sword would still be a multi layered patternwelded sword. It doesn't take that much more effort to twist some of the bars before the final assembling of the blade. There's even carbon free soft iron swords that were patternwelded, which shows that the patternwelding wasn't anything exclusive if it was done on such a low end sword.

|

|

|

|

|

Gary Teuscher

|

Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 8:45 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 8:45 am Post subject: |

|

|

What I menat by the bog iron I guess was that there would be non-homogenous types of material to use, as opposed to one piece from standard ore. Apparently it was more the blast furnace technology that made pattern welding less important, getting the temperature high enough to melt as opposed to high enough to weld as with a bloomery furnace.

I'm curious, is a pattern welded blade any better than a blast furnace produced one? It certainly would be slower to produce. I wonder how many pattern blades were done after the blast furnace was common technology, and why?

| Quote: | | The main reason for patternwelding (other then simple piled constructions) is because it's pretty. The more complex the pattern, the more pimped out your sword. And particularly in the early days there was a lot of showing off by more complex and unique patterns. |

Maybe that's the reason why it is done now - but originally it had more of a purpose than to "pimp out" your sword.

| Quote: | Pattern welding was developed in both Europe and Asia as a means of averaging the properties of iron and steel. Iron is too soft and flexible for use in weaponry, while the hypereutectoid steel produced in the ancient world was too hard and brittle. The earliest known use of pattern welding in Europe is from an 8th century BC sword found at Singen, Württemberg in Germany (Salter & Ehrenreich 1984). The Celts originally employed alternating rods of iron and steel twisted together and then welded with the use of the bloomery furnace which can bring iron and steel (carburized iron) to a welding temperature, but not melt them. In Asia, the carbon content of the iron and steel produced in the bloomery process was highly variable, and repeated folding and welding was employed to remove excess slag and impurities from the metal and to homogenize it. Two or more batches of fairly uniform steel (each batch with a different composition) were then welded together. The different steels result in blades with improved mechanical properties and a distinctive wavy pattern being observed after etching. The technique first appeared about 300 BCE, and by 500 CE/AD was being used by the Merovingian dynasty. Through their successors, the Carolingian dynasty, the technique became common throughout Europe by about 700 CE/AD. The period of European pattern welding, then, encompasses the Celto-Roman Iron Age through the Migration Era. Introduction of the blast furnace brought it to an end.

By the 9th century in Europe, the blast furnace became available and with it the ability to create homogenous high carbon steel. The need for pattern welding all but died out for other than cosmetic applications. During subsequent centuries the technique was slowly lost, and by 1300 there are few examples of its use. The technique survived, however, in Scandinavia, where good quality iron ores and charcoal were widely available.

It was during this same period that Damascus steel was being produced in the Middle East, and similarities in the markings led many to believe it was the same process being used. Swords made by pattern welding are sometimes said to be "Damascus blades", although the manufacture of Damascus steel is entirely different. The terms "Damascus", "Damask", "damascening", etc. are complete misnomers that have nothing at all to do with European pattern welding technology. |

|

|

|

|

Kirk Lee Spencer

|

Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 9:15 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 9:15 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Gary Teuscher wrote: |

...I've heard 2 schools of thought on pattern welding. One is it was done to produce a higher quality blade, even though it was less efficient time wise.

The other was that it was necessitated by having small amounts of bog iron to work with - the quality was not any better, but it required a lot more work, but for some iron poor cultures this was their only option.

I would assume there are some truths to both. |

Hi Gary...

There has been alot of speculation on this question of patternwelding. The pendulum seems to be swinging in the direction that Jeroen suggests... patternwelding designs are decorative and fashionable.

However, if I remember correctly, early on most believed that it had something to do with the quality of the sword by way of carbon migration occurring during the bending and twisting and welding making for a more steely iron. However when studies were done on the carbon content of these blades the results showed extremely wide variation in quality.

It seems that in asking the question of steel quality we may be superimposing our modern understanding of steel formation onto celtic and medieval minds. I read somewhere that it wasn't until the industrial revolution that it was even recognized that steel was formed by adding carbon. Until then, it was much more common to believe that the higher quality of the iron was caused by removing something in the process rather than adding something. This is interesting to me because one thing that the piling and layering and torsion of the iron does do is break up the running slag inclusions so that it is less likely that the weakness of the inclusions would align like perforations and cause blade failure. In this sense, it pattern welding does make for a stronger blade.

The fact that the cutting edges welded on the iron cores show a consistently higher quality shows that, as you say, they may have had a shortage of what they recognize as really "good stuff" and reserved it for the business part of the sword, using milder slaggy stuff for the core.

Because of the variables in the quality of source material, we find there are many other variables besides carbon content and slag inclusions. Things such as phosphorus content. It seems that in some blades phosphorus is present which would make the blade harder but also more brittle. However it also allowed for more work hardening. This is important in that many of these blades, if not most (I think this is right) show little to no sign of quenching and tempering but many were work-hardened (hammering the surface of the iron to compact it and make it harder).

I have read that when large quantities of the "good stuff" were discovered (or rediscovered) in central Europe around Solingen the pattern-welded core began to rapidly disappear in the blades of 9th-10th century swords. However there were thin veneers of pattern welded iron applied in the fullers for a while and even some engraving or etching that resembled pattern welding. This suggests that there may have been a generation or two that did not want to use the "new fangled" mono-steel, preferring the old school. To tap into this "old fogie" market they dressed up the monosteel blades with some pattern welded veneer in the fullers. Or as Jeroen mentioned it might simply have been the "bling" factor. Monosteel blades were just too boring without a little pazazz in the fuller.

We should also remember that it was the Middle Ages, a time when swords were not for collecting but for killing, so... there probably were all kinds of superstition involved. And, while these more mystical variables do not sit well with our modern minds, in terms of quality control, they were probably the rule rather than the exception to medieval smiths.

If we could go back in time and talk with the swordsmiths and ask them why patternwelding made a better sword they may shock us with a long dissertation on how the snake like undulations adds venom to the bite of the blade for a faster kill and how the palm tree causes the iron to spring to life and the nets and knots help to bind the sword of your enemy.

take care

ks

Two swords

Lit in Eden’s flame

One of iron and one of ink

To place within a bloody hand

One of God or one of man

Our souls to one of

Two eternities

|

|

|

|

|

Gary Teuscher

|

Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 11:15 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 16 Dec, 2008 11:15 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

How about the BLoomery vs the Blast furnace issue?

|

|

|

|

|

Jeroen Zuiderwijk

Industry Professional

|

Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 1:23 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 1:23 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Gary Teuscher wrote: | | Maybe that's the reason why it is done now - but originally it had more of a purpose than to "pimp out" your sword. |

How can you be sure? The decoration of the hilt has no function aside from pimping out the blade either. Considering that the hilts were heavily pimped out, it's no surprize if they did anything to pimp out the blade as well, within the limits that it doesn't sacrifice any functionality. Twisting the billets of the sword core has no mechanical advantage (linear piling is probably even slighly stronger), but it does make the sword look much more attractive. And it may have had a special meaning as Kirk mentioned, which may be the reason why this fasion survived that long.

Last edited by Jeroen Zuiderwijk on Wed 17 Dec, 2008 2:42 am; edited 1 time in total

|

|

|

|

|

Jeroen Zuiderwijk

Industry Professional

|

Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 2:29 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 2:29 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Gary Teuscher wrote: | | How about the BLoomery vs the Blast furnace issue? |

That's an issue not easily answered (at least not by me). The history of steel production is a very complex one, and if you don't delve deep enough into it and know all the details, you'll end up making the wrong conclusions. Blast furnaces produce cast iron. The arrival of blast furnaces around 1100 doesn't mean they were making cast steel. The first cast steel that I know was produced in Europe was in the 18th century (Benjamin Huntsman). But from what I understand, even that steel was made from steel that was already carburized by cementation (blister steel) and the melting was to remove the impurities. And just to show how complex the issue is, in the 18th century before the Huntsman process, blister steel was made from pig iron that first had the carbon removed, then carburized again by cementation into blister steel. That steel was piled and welded into what's called shear steel. And that's probably still oversimplifying it. But it shows that eventhough the iron was made by removing the carbon from cast iron, it was still turned into steel the same way wrought iron was turned into steel in ancient times (cementation in solid state, then piling and welding to homogenise the steel).

I don't know how steel was made, or if it was made at all from pig iron in the 11th century. But from metallurgic analysis of several Ulfberht swords, it shows that they were made consistantly of a good quality steel. And from then on, these plain steel blades with Ulfberth, Inglerii marks on them become very popular due to their quality. How that steel was made and what exact technological innovations resulted to this not easily answered without further study. It's possible that it wasn't even due to technological changes, but to the process being more industrialy organized rather then small workshops. It's roughly around that time that Solingen starts up to become a major production center for sword blades f.e.

|

|

|

|

|

Gary Teuscher

|

Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 6:49 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 6:49 am Post subject: |

|

|

To throw another issue into the equation, my understanding is "Damascus Steel" was made in a process different but in some ways similar to pattern welding. Anyone versed in Damascus Steel?

I guess it is funny how little we truly know about ancient swordcrafting techniques, and perhaps what is also funny how little they knew, why certain things worked well and others did not.

You have carbon introduced to the iron, phosphorous, even alloys with Vanadium, Tungsten, Nickel invloved. From what I know glass was added to Wootz steel to better remove the slag and impurities. One wonders if many of these ancient smoths really knew what they were intruducing into the basic iron.

My guess it waa trial and error situation, with certain techniques producing better swords and these techniques being then used by swordsmiths, the process rather slow from an evolutionary standpoint. It could aslo explain why the "tried and true" method of pattern welding, even though slower for manufacture was continued after better technology was available. Or perhaps pattern welding produced better swords, I don't know.

We do know that the smiths had the right idea about wanting a soft blade for fexibility, but also a harder blade for cutting. I would think they knew what they were doing when trying to incorporate both of these in one, be it a softer core and harder outside, or a harder edge on a softer blade, or even a laminate of different hardness materials.

With the Forge vs Bloomery thing - with a little reading, I have found the line between the two to be rather grey. With advances in Bloomeries, my understanding is the temepratures got hot enough to melt iron as time went on, making the blast furnace more efficient, but not always a step up in technology.

I do believe though that in the Middle ages, particularily the earlier period, the "pimping out of the sword" would have been secondary to a quality weapon, they were more concerned with functionality I would think. This may have been a carry over from when this was the best way to make a functional weapon, and perhaps it still was the best way to make a functional weapon for some time.

|

|

|

|

|

Jeroen Zuiderwijk

Industry Professional

|

Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 7:23 am Post subject: Posted: Wed 17 Dec, 2008 7:23 am Post subject: |

|

|

| Gary Teuscher wrote: | | To throw another issue into the equation, my understanding is "Damascus Steel" was made in a process different but in some ways similar to pattern welding. Anyone versed in Damascus Steel? |

We don't normally use that term, as it's being applied to both patternwelded and wootz steel. Wootz (also called bullat) is a crucible steel that shows patterns in the metal due to carbon segegration (aided by impurities like vanadium). Wiki on wootz: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wootz

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2026 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|