I've just been working on an early iron age knife, and I was surprized at how deep into the metal the corrosion goes due to the forging, and just how much metal has to be ground away to remove all the traces of forging and get a clean finish. I realize there's probably a lot of factors involving the corrosion (oxydizing of the fire, time spend forging, forging temp, type of steel etc. etc.). But if this level of corrosion is in any way indicative to what the original smiths may have been faced with before the arrival of power tools and metalworking files, then creating such a fine finish is quite a daunting task.

So that brought me to the question, how far did the ancients go in finishing their forgings? How far was the average knife or sword finished after forging in say the iron age, Roman period, migration period etc.? There would have been a lot of variation of course. But my guess is that a great majority of tools and weapons that were made may have been finished just far enough to make them functional. There probably also were a lot of pieces with a mostly cleaned surface. But considering that removing the last 10% of the marks generally takes 90% of the work, I'd guess a lot of pieces with a lot of attention to a nice finish would still have various spots here and there. It would be very hard to distinguish these marks from the corrosion after deposition on originals though. Though if the surface is still in a good condition, the shape and nature of forging marks could potentially help recognizing them.

Looking at some ancient pieces, I could pick out some examples with the surface preserved that indicate that they were left in forged state, with hardly any grinding done on them. Below you can see an iron age knife and leather knife. Both still clearly show the hammer marks on them, which means that little to no grinding was done on them.

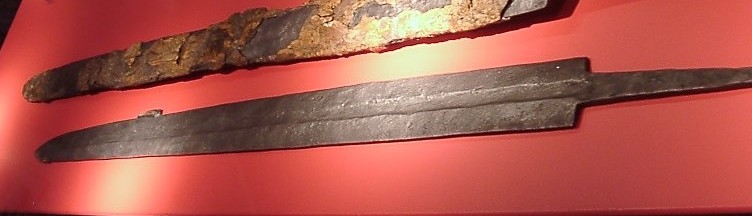

Another example is a migration era sword. This sword is hardly more then a bar of iron with an edge thinned down and a fuller (crudely) hammered into it. The raw shape of this blades make it highly unlikely that much grinding work has been done at it as well.

I realize of course that these are probably the low end pieces. There's definate examples of very finely finished pieces. Especially in patternwelded swords f.e., there was an enormous amount of grinding work involved. So by that time, I assume the grinding methods were either just efficient enough to make it worthwile, or they didn't mind spending huge amounts of manhours on a blade (and as a result also having a low production quantity).

Iron age knife and leather knife

Sword from the Netherlands, 450-600AD