My focus is mainly on Central Europe and in that context, in the late medieval artwork especially in German, West Slavic (manly Czech or Polish) or Flemish artwork what you see depicted for battle are primarily the relatively small weapons spanned by the rack and pinion cranequin type spanners, and to a lesser extent, the somewhat larger weapons spanned by the windlass. Some depictions of the goats foot or wippe, and some of spanning with belt hook or the like, but not as much.

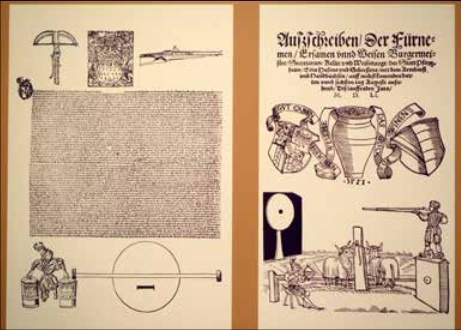

Examples would include images from the Swiss chronicles, Polish and Czech manuscripts, (Balthasar Behem Codex from Krakow is a good example) German manuscripts (like the Von Wolfegg housebook), and religious art such as various depictions of St. Sebastian. The prestigious weapon is usually the cranequin weapon.

By comparison if you look at some of the illuminated versions of Froissart from France and Flanders (for a French audience), they often depict the windlass or pully type or belt hooks.

In her War Book, Christine de Pisan clearly describes several distinct types of crossbows and spanners, unfortunately the translation just says "other crossbow" and "another crossbow" since the translator didn't know the period terms, and I've been unable to find a transcription of the original text.

This corresponds with the Teutonic Knights records, urban militia ordinances and records related to the Hungarian Black Army, which all point to an emphasis on the cranequin type weapons as the most preferred, with the stirrup crossbows coming second. I don't think the solid wood ones were used in a military context except in defense of fortifications or towns. They would be fine for hunting though probably.

Note in this detail pic from the Bern Chronik (attached / bottom) and one of the two St. Sebastian images where you can see it, he has a crossbow with a foot stirrup but he's spanning with the cranequin and not using the stirrup. However Bern Chronik also includes some images of belt-hooks.

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]