| Author |

Message |

|

Isaac H.

|

Posted: Sun 01 Feb, 2015 11:04 pm Post subject: Breaking the Point : 17th Century Choosing of a Sword Posted: Sun 01 Feb, 2015 11:04 pm Post subject: Breaking the Point : 17th Century Choosing of a Sword |

|

|

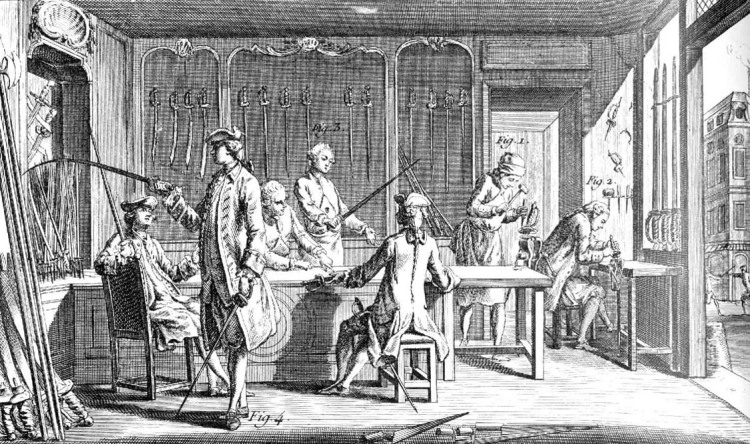

Many people on this forum purchase swords...

We buy them for many reasons : for the sheet enjoyment of possessing them, for historical interest, and some for the practice of martial art or reenactment. Yet, there is one reason we will never be able to experience... purchasing a sword that is intended to do what swords were originally meant for : to defend life, and to take life. No,it is the highest unlikelyhood you will ever trust your very life to your sword. I have been researching this forgotten perspective lately. I teach historical fencing ,and will be giving a presentation at a local sword symposium about historical necessities that are no longer part of practicing the art of historical swordsmanship . One of the topics I am covering is the gentlemanly choosing of a sharp sword for dueling and defense purposes. Several historical treatises address this subject, but my chosen source is 17th century French fencing master Monsieur L'Abbate's Sur L' Art En Fait D'Armes , translated into English in 1734 as The Art of Fencing,or,The use of the Small Sword.

In the first chapter , L'Abbat gives us a very practical premise , as follows below :

" Courage and Skill being often of little use without a good Weapon, I think it necessary , before I lay down the Rules for using it, to shew how to chuse a good Blade ,and how it ought to be mounted..."

He later continues on ,giving his opinion on the proper methodology of choosing a good blade:

" ... In order to chuse a good blade, three Things are to be observed : First, that the Blade have no Flaw in it, especially across, it being more dangerous than Length-way. Secondly, That it be well tempered ,which you'll know by bending it against a wall or other Place; if it bend only towards the Point; 'tis faulty , but if it bend in a semi-circular Manner ,and the Blade spring back to Straightness, 'tis a good Sign; If it remains bent it is a Fault ,tho' not so great as if it did not bend at all; for a blade that bends being of a soft Temper, seldom breaks; but a stiff One being hard tempered is easily broke .."

The next section is what I am particularly interested in :

" The third Observation is to be made by Breaking the point, and if the Part broken be of a grey Colour , the Steel is good ; if it be White 'tis not : Or you may strike the Blade with a Key or other piece of Iron , and if he gives a clear Sound, there is no hidden fault in it.... "

So here, amonst other antiquated behaviors, we see a most curious practice . A gentleman would not be found at fault or thought abusive if he snapped the point off a sword he was interested in. Talk about tire kicking !

A few specific questions :

Is this practice of snapping off the point while selecting a sword as commonplace as L'Abbat seems to suggest? Or perhaps only a regional practice? ( L'Abbat lived in Toulouse, south-western France)

I suppose the tip could be reground with relative ease, but the idea still seems destructive ,considering the expense of a sword. Has this technique been documented in other works?

For those of you with knowledge of metalurgy, what is indicated by the steel color L'Abbat describes? All broken steel I have seen has been a grey color. What would 'white' coloration indicate about the heat treatment? Is that a flaw that does not exist in modern alloys? I've always thought in terms of grain structure, not coloration.

I am planning on actually breaking a sword tip as part of the presentation, so I would appreciate any input .

All thoughts on this topic is most encouraged !

Attachment: 163.8 KB Attachment: 163.8 KB

Wounds of flesh a surgeons skill may heal...

But wounded honor is only cured with steel.

We who are strong ought to bear with the failings of the weak and not to please ourselves.

Each of us should please his neighbor for his good ,to build him up.

Romans 15:1-2

|

|

|

|

|

Leo Rousseau

Location: France Joined: 27 Dec 2013

Posts: 19

|

Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 12:57 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 12:57 am Post subject: |

|

|

I didn't new this treatise but thank you for speaking about it. I checked the original text in French and here is what it say :

" La troisième remarque c’est de faire emousser ou casser la pointe,si dans

l’endroit cassé elle est de couleur grise, le fer est bon, si elle est blanche c’est le contraire."

which could translate :

"The third observation is to have the point blunted or broken [The use of the French indirect mode "faire emousser ou casser" may imply to ask the maker of the blade to do it himself and show you the section, which may imply a somewhat less destructive precess than the one explained in the English translation"]. If where it is broken the colour is gray, the iron [sword in this context I think] is good, if it is white it is not"

About the matter of colour here is what I think : a well made steel with a homogeneous carbon repartition is gray. However, a steel with less carbon, bad carbon repartition or no carbon at all will be lighter end tend to white.

I hope it will help !

Leo

|

|

|

|

|

Lafayette C Curtis

|

Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 9:25 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 9:25 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

If I'm not mistaken, Liancour makes the same recommendation about checking the broken tip of a sword. This is a subject that has puzzled smallsword HEMAists for quite a while now, and personally I lean towards the interpretation that the cutler/sword-seller would already have a pre-broken blade for the buyer to inspect. I don't really know the significance of the colour since to my modern eyes "whiter" steels tend to signify stainless rather than spring/carbon steel, but if I'm allowed to speculate then it might have something to do with a "powdery" vs. clean break.

|

|

|

|

Luka Borscak

|

Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 9:50 am Post subject: Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 9:50 am Post subject: |

|

|

|

Yes, I think this colour difference might represent smooth vs more grainy steel structure.

|

|

|

|

|

Isaac H.

|

Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 6:30 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 6:30 pm Post subject: |

|

|

Thanks for the replies so far, everyone. Special thanks to Leo for the original French and translation, that was very insightful.

Some gentlemen on another forum (bladesmithing) are leaning towards the same thing that has been suggested here, that the grain structure of the break in a properly heat treated sword reflects light differently than one with improper heat treatment.

An poor interior grain structure tends to have a sparkly/ crystalline structure that would indeed appear white in contrast to properly heat treated steel, which would have a clean break, with a smooth,dull grey cross section.

Mr Curtis, thank you for mentioning Liancour's treatise, I have not studied it. His mention of the breaking of the tip as well does lead me to believe it was a fairly common practice, at least in France.

Attachment: 57.44 KB Attachment: 57.44 KB

Top two pieces of steel illustrate a "white" appearance [ Download ]

Wounds of flesh a surgeons skill may heal...

But wounded honor is only cured with steel.

We who are strong ought to bear with the failings of the weak and not to please ourselves.

Each of us should please his neighbor for his good ,to build him up.

Romans 15:1-2

|

|

|

|

|

Peter Messent

|

Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 7:53 pm Post subject: Posted: Mon 02 Feb, 2015 7:53 pm Post subject: |

|

|

I agree that the color refers to grain structure. Interestingly, this is still done by many bladesmiths. There was a very insightful thread on Bladeforums regarding the difference in granular structure (and the resulting difference in strength) that can be accomplished with normalizing steels. It includes pictures of the grain of a piece of steel that was broken after each normalizing cycle:

http://www.bladeforums.com/forums/showthread....RAIN-SHOTS

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2026 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|