Posts: 468 Location: Sioux City, IA

Mon 30 Oct, 2017 12:13 pm

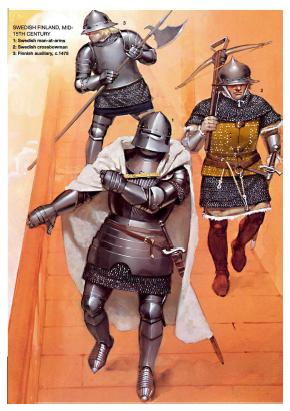

As others already said, the fact that Sweden a poor country to western medieval standards doesn't mean that there wasn't NO rich people living at it. That will simply mean there were lesser rich people there, so it was possible that swedish armies would tend to be lesser well-armored than, for example, a german one. Armor was, of course, expensive, but affordable enough for any squire, knight or men-at-arms to have one. Swedish nobility actually spent more resources at building castles, ships or waging wars than actually buying armor or preserving armor for themselves. If you look at Paul Dolstein sketches of his campaigns in Scandinavia, he shows Swedish men-at-arms with contemporary (or perhaps a decade older) full armor. There are also an example of imported armor from Germany to a 16th-century Swedish king.

When an army from Catholic Europe shows relative lack of armor, the reason usually rests on cultural factors rather than actually poverty: Ireland, for example, only adopted armor due to norman and Viking influence somewhere in 12th century, and even so they never went as far as the basic mail hauberk and padded gamberson; even if a Irish chieftain had enough money to actually cover his gambeson with silk imported from Scandinavia and ride a very expensive horse even to English standards. Scottish Highlands usually had similar standards for heavy armor. In Spanish Kingdoms, although some of the nobility actually had the newest harness and the poorer nobility had outdated armor, most of the infantry and poorer classes usually fought with little-to-any armor (in 1385's Castillian Ordinnance, neither the javelinmen nor the crossbowmen were required to have armor).

I'm curious, however, regarding how poor or rich was Sweden compared to its neighbors: Poland and Denmark-Norway

-----

| Daniel Staberg wrote: |

Where have you fund the claim that the Swedish nobility was too poor to aford amour? It certainly isn't supported by any research I know of. The poverty of Sweden as whole at this time only limited the size of the wealthy class who could equip themselves in this fashion it did not remove that group altogether. While we have no detailed data on how many "men-at-arms" the Swedish nobility could provide in the 15th Century there are detailed informantion from 16th Century.

In those years the Swedish nobility was required to provided close to 1200 men-at-arms in return for the freedom from taxation. However the largest number of men-at-arms servign in the field at one time was 642.

To this one must add the men-at-arms of the Royal household troops, durign the time in which lance armed men-at-arms were in used these numbered 200-300 MAA mantained by the King using his own resources.

So eve a maximum effort could not provide more than 1000 men-at-arms with 500-600 MAA serving in the field at any one time being a more likely number.

Cheers

Daniel |

The obligation of fielding 1,200 men-at-arms was froom fifteenth or sixteenth century? In sixteenth century the heavy cavalry lost most of its importance (unless in France), so I don't know with we could actually use this a acurrate mirror to the earlier century. There aren't no other description regarding the number of men-at-arms Sweden was fielded in battle?

Also, the 200-300 strong household knights was actually a fairly common number to late-medieval western armies. England had one with similar numbers.

| Martin Wallgren wrote: |

I would guess with thick wool under the armour. Or not as much armour as in the summer.

Last winter we had a small show at Gene Fornby, Sweden and it was like minus 14 degrees Celsius out and we had to have extra soft hats under the roman helmet not to freeze our ears of. Otherwise it´s just like my grannie said, no winter is too cold it just a matter of layers of clothes. |

I don't know any reference for underneath extra-clothing, but the Swiss usually drank more wine and local sorts of alcoholic beverages to counter the marches in cold winter.