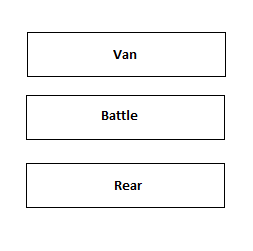

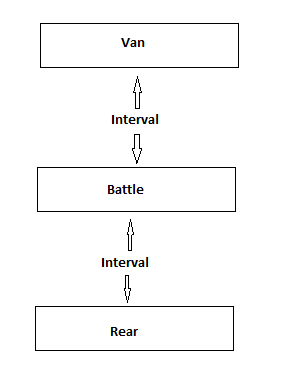

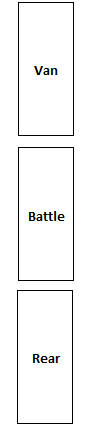

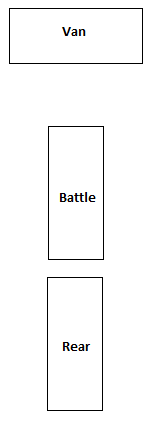

Maybe it's because of movies, video games or later historical battle that I always held the notion that armies were deployed in one or more lines across a battlefield, wider than it was deep. However recently I came across some text which suggests something else. I knew many medieval commanders divided their army into separate entities such as vanguard, mainguard and rearguard, and that sometimes separate entities of the army were called 'battles'. Of course the vanguard would be at the front of an army traveling and I read quite a few primary sources in which the vanguard engages an enemy position first while the rest of the army has to catch up. I read that in pitched battles these guard or battles as they were called were deployed in a more linear formation with the vanguard holding the left, mainguard the middle and the rearguard the right (or the other way around).

I'd imagined this is something sensible to do as it allows your army to engage the most of its soldiers, protect it's flanks and overlap the enemies flanks. However in some pitched battle it almost appears as if these larger formation were deployed in a column formation rather than a wider line formation. In the battle of Crecy the crossbowmen of the French were send forward to Skirmish a little ahead of the main army and when they retreated they threw the first group of horsemen that followed them in confusion.

Then there is the famous battle of Agincourt

| Quote: |

| When the French observed the English thus advance, they drew up each under his banner, with his helmet on his head: they were, at the same time, admonished by the constable, and others of the princes, to confess their sins with sincere contrition and to fight boldly against the enemy. The English loudly sounded their trumpets as they approached, and the French stooped to prevent the arrows hitting them on the visors of their helmets; thus the distance was now but small between the two armies, although the French had retired some paces. Before, however, the general attack commenced, numbers of the French were slain and severely wounded by the English bowmen. At length the English gained on them so much, and were so close, that excepting the front line, and such as had shortened their lances, the enemy could not raise their hands against them. The division under sir Clugnet de Brabant, of eight hundred men-at-arms, who were intended to break through the English archers, were reduced to seven score, who vainly attempted it. True it is, that sir William de Saveuses, who had been also ordered on this service, quitted his troop, thinking they would follow him, to attack the English, but he was shot dead from off his horse. The others had their horses so severely handled by the archers, that, smarting from pain, they galloped on the van division and threw it into the utmost confusion, breaking the line in many places. The horses were become unmanageable, so that horses and riders were tumbling on the ground, and the whole army was thrown into disorder, and forced back on some lands that had been just sown with corn. Others, from fear of death, fled; and this caused so universal a panic in the army that great part followed the example.

The English took instant advantage of the disorder in the van division, and, throwing down their bows, fought lustily with swords, hatchets, mallets, and bill-hooks, slaying all before them. Thus they came to the second battalion that had been posted in the rear of the first; and the archers followed close king Henry and his men-at-arms. Duke Anthony of Brabant, who had just arrived in obedience to the summons of the king of France, threw himself with a small company (for, to make greater haste, he had pushed forward, leaving the main body of his men behind), between the wreck of the van and the second division; but he was instantly killed by the English, who kept advancing and slaying, without mercy, all that opposed them, and thus destroyed the main battalion as they had done the first. They were, from time to time, relieved by their varlets, who carried off the prisoners; for the English were so intent on victory, that they never attended to making prisoners, nor pursuing such as fled. The whole rear division being on horseback, witnessing the defeat of the two others, began to fly, excepting some of its principal chiefs. |

As we can see the first wave consisted of 800 men at arms on horseback followed by three battles/guards. Again each entity of the army was routed piecemeal and brought chaos and confusion unto the next in line.

Another battle of the 100 years war which saw a similar setup (and resulted in the same side winning again) was the battle of Nájera in which Bertrand du Guesclin commanded the first division while the king of Castile commanded a second part a bit further back.

The last battle I will name which appears to have followed a similar pattern occurred during the siege of Neuss, what follows are two eyewitness accounts of the same battle. Here the positioning of the army is described in detail.

| Quote: |

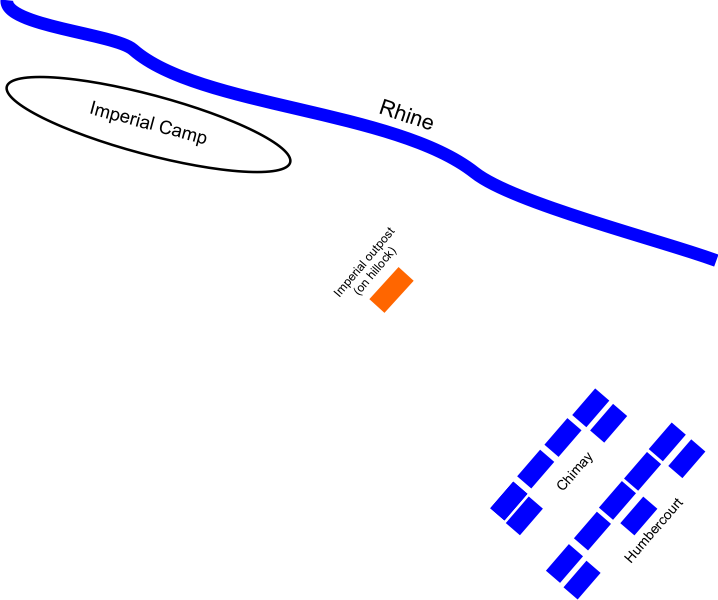

| As to our news, last Tuesday 23 May the Emperor struck camp in order to approach nearer our siege, but he only passed a wood which was very near him and pitched camp on this side of the wood. As soon as we were definitely informed of his move, which was at about 10.00 a.m., we at once caused the household troops and the companies of our ordinance to take the field, leaving our said siege defended and provided with sufficient forces to resist the sallies of the people in the town and to prevent those beyond the Rhine, who were in considerable force, from crossing to this side to help and revictual those in the town. After making these dispositions for the defence of our siege we took the field and marshalled all our troops on this side of a river which was between us and the Emperor, in the following way.

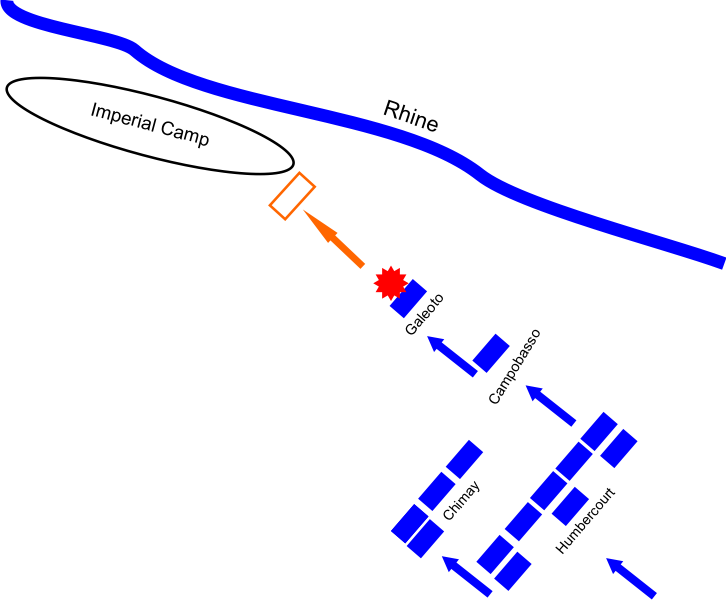

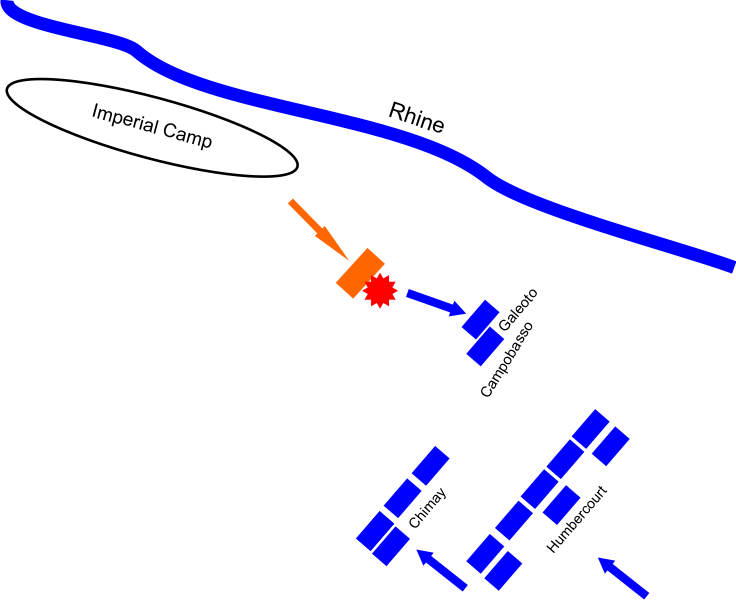

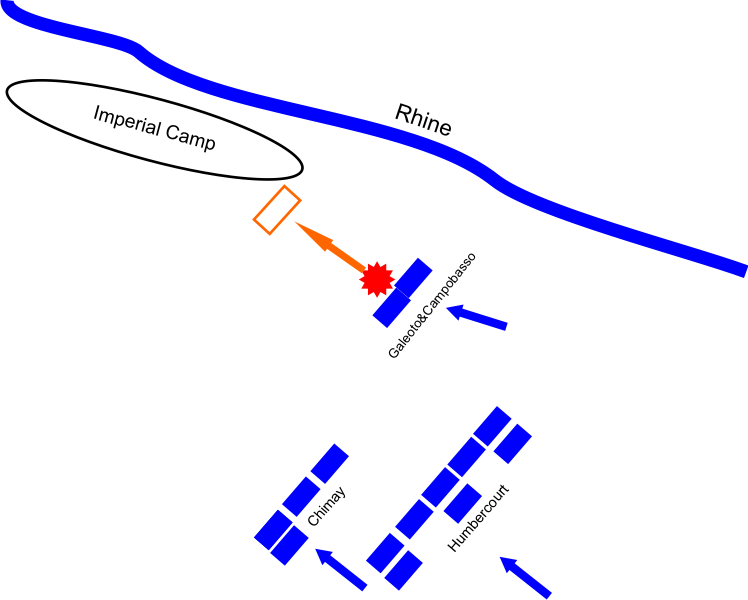

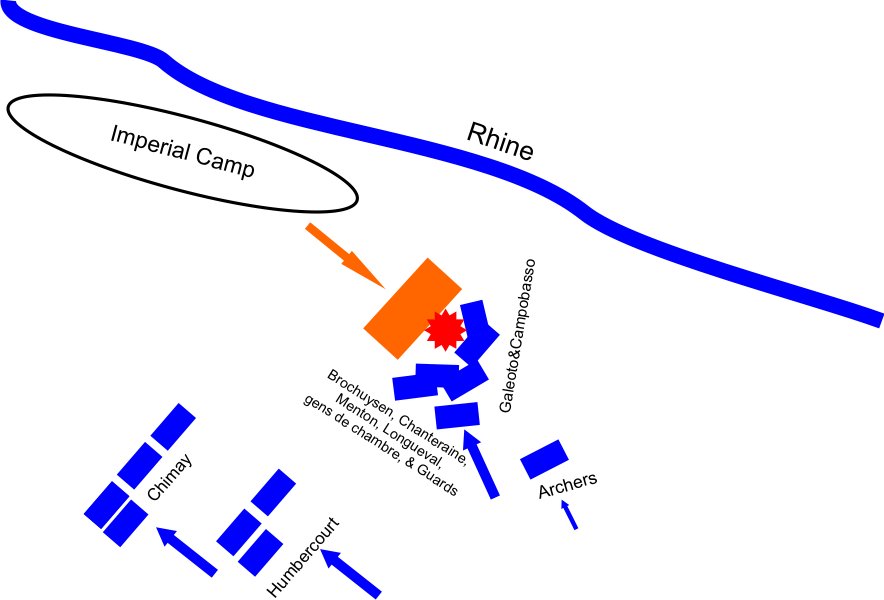

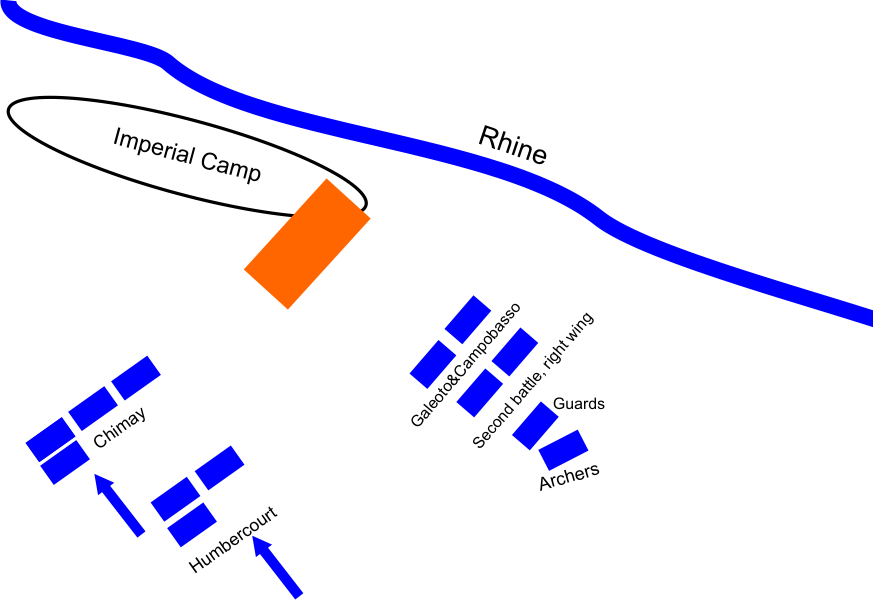

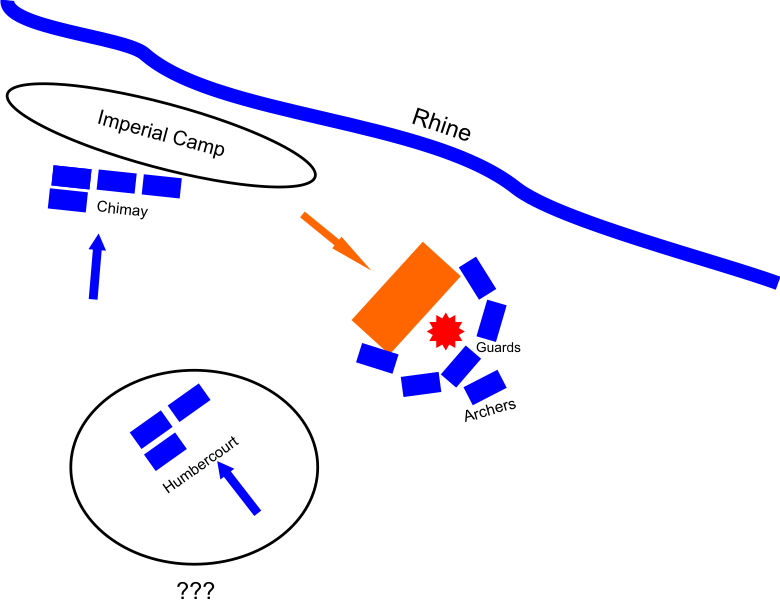

Deployment of the first battle In the first battle [we posted] all the infantry, pikemen of our ordinance, and the English archers both of Messire Jehan Middleton’s company and of our household and guard, together with the infantry belonging to [the companies of] the lords of Fiennes, Roeux, Céquy, Haines, and Peene and other enfeoffed lords. [Among] all these pikemen were intermingled the archers in groups of four, so that there was a pikeman between every group of archers. On the right wing of these infantrymen we posted Messire Jehan Middleton’s mounted men-at-arms, as well as those of Jacques Galliot’s company, all in a single squadron, with the count of Campebasse and all his men as the reserve for this wing. On the left wing of the infantry we posted the enfeoffed lords and their men-at-arms with the count of Celane and his company, all in one squadron and, for their reserve, the two companies of Messires Anthoine and Pierre de Lignanne, also in a single squadron. We appointed our cousin, councillor, and chamberlain the count of Chimay [commander-in-]chief of this battle. Deployment of the second battle In the centre of the second battle we placed the squadron of chamberlains and gentlemen of our chamber and, in reserve, the mounted guards under the command of Messire Olivier de la Marche, our maître d’hôtel, as their captain. In a squadron behind and some distance to the right of the said chamberlains and gentlemen of our chamber [we placed] all the archers of our ordinary guard and all the archers from the companies of Messire Regnier de Brochuysen, the lord of Chanteraine, George de Menton, Jehan de Longueval and Regnier de Vanperghe. The last three of these were knighted that day. On the right wing of the said archers we posted the men-at-arms of the companies of the said Messire Regnier de Brochuysen and Chanteraine with, in reserve, the men-at-arms of the companies of the said Messire George de Menton, Jehan de Longueval and Regnier de Vanperghe, all in one squadron. On the left wing of the said chamberlains and gentlemen of our chamber we posted the archers of our bodyguard and those of the companies of Philippe de Berghes, who was knighted then, and of Philippe Loycette, and on the flank of these archers all the men-at-arms of the companies of the said Messire Philippe de Berghes and Loycette in a single squadron with, as their reserve, the gentlemen of the four estates of our household, in one squadron, commanded by Messire Guillaume de St. Seigne, also our maître d’hôtel, and, under him, by the chiefs of the said four estates. This battle was commanded by the lord of Humbercourt, also our cousin, councillor, and chamberlain, as commander-in-chief in the place of our first chamberlain, [together with] the count of Joigny and the lord of Bièvres. [ Linked Image ] Order of march, river-crossing After these battles had been organized in this way a certain amount of time elapsed, more than was necessary, because the companies did not arrive soon enough at their appointed places. Nevertheless, regardless of the time, we crossed the said river at a ford which was not too deep, firm with a good bottom and, because of the narrowness of the said ford, we made the reserve of the right wing of the first battle march across it in files, the men-at-arms with their coustilliers (light cavalry/mounted infantry) and pages on their right and likewise in file after them went the right wing and all the archers of pikemen of this wing. Then followed the archers and pikemen of the left wing and, after the wing, its reserve, and, in just the same way, the second battle crossed, the reserve of the right wing followed by the wing , the archers of the same wing, and all the rest of the second battle in similar order to the first. After the reserve of the left wing, which consisted of the gentlemen of the four estates, our guard, which constituted the reserve for the said squadron of chamberlains and gentlemen of our chamber, crossed over. Deployment on the other side of the river Because their camp, which backed on to the Rhine, extended towards us, and we were nearest to this end of it, the enemy, thinking that we would come this way, had placed most of their artillery there. They had even trained the artillery in the encampment on the far side of the Rhine to fire in front of this end of their said camp where they thought we would attack. But, in crossing the river, we made all the above-mentioned formations advance to the left of the said camp, that is to our right, and move towards the above mentioned wood which they had passed through on the way to their camp, and we made all the formations and their reserves extend into the same order in which they had been on this side of the river. With regard to our artillery, we passed it over a bridge near the ford after the said battles, which, because they had been in order and crossed the ford as described above, were very quickly reorganized so that, when we crossed the said bridge after the artillery rather than passing through the ford after the said battles, we found they had all crossed over and were in excellent order. They were a very fine sight. It is a fact that on our arrival we moved them further towards the said wood to dodge the fire from over the Rhine and from the side where most of the [enemy] artillery was placed, as well as to gain the sun and the wind which was causing great deal of thick and stinging dust, and so that we could approach the left-hand side of the Emperor’s camp, where it was fortified, but not so well as on the other side. battle We gave the cry of Notre Dame! Monseigneur St. George! and our usual cry of Bourgogne! but, before we made any of our formations march, we moved up our artillery three or four bow-shots in front of us, together with the Italian infantry which had not been in any of the above-mentioned formations, so that it fired at and shot into the Emperor’s camp in such a way that no complete tents, pavilions or lodgings were left standing and people could only remain there with great difficulty. Then, in the name of God, of our Lady and of Monseigneur St. George we gave the signal for the troops to march. This done, the trumpets began to sound and everyone marched joyfully and with smiling faces, making the sign of the cross and recommending themselves to God; the English, according to their custom, making the sign of the cross on the ground and kissing it. Then they all shouted the above-mentioned cry. Because the Germans held a [certain] hillock we caused Jacques Galiot to march there. He formed the right wing of the [first] battle with the count of Campebasse as his reserve. They captured it, and the Germans were forced to flee over the flat ground between the hillock and their camp. During the capture of this hillock several of the Emperor’s people were killed. Realizing that they needed to defend and guard this flat ground to protect the security of their camp, a large number [of the enemy] sallied out both on foot and on horseback and attacked the said Jacques, who was forced to retreat towards the count, his reserve. He had gone some distance ahead of him at the first attack but now the count advanced with his reserve as Jacques fell back on him and they attacked again together and broke the enemy, putting them to flight back to the camp. Here too several of the enemy were killed. Jacques and the count had no archers with them, for the count of Chimay had marched his men too far to the left, so it was not possible at this moment to attempt anything else against the enemy and, because of the artillery fire from the camp, Jacques and the count withdrew down a valley. After this retreat more troops than before, both infantry and cavalry, sallied out of the Emperor’s camp to attack Jacques and the count, who let us know of this. So we had to send them the reserve of the right wing of the second battle, comprising Messires George de Menton, Jehan de Longueval and Regnier de Vanperghe and, immediately afterwards, we sent the reserve of the squadron of our chamberlains, that is, the guards under Messire Olivier de la Marche, and, because they needed archers, we ordered off the entire right wing of archers of the second battle. But the men of this wing, under the command of Messire Regnier de Brochuysen and the lord of Chanteraine, moved quicker than their archers who, because they were on foot, could not keep up with them, and these companies, of Messire Regnier, the lord of Chanteraine and our guard, united with Jacques and the count without waiting for the archers and attacked the [enemy] force which had sallied out, in which were the duke of Saxony and other princes, and drove them back into their camp but, because they did not have with them the archers of the right wing of the second battle, which we had sent them, they were forced by the artillery fire to withdraw to the above-mentioned valley. After this retreat, all the princes came out, deploying the imperial banner, which the duke of Saxony carried, accompanied by all their cavalry and a great number of infantrymen, to attack our people. They forced the right wing of the first battle and its reserve back onto the right wing of the second battle and its reserve, both wings and reserves falling back as far as our guard, which held firm. Seeing this, we took a squadron which had not yet been allocated and went with it towads the right, in order to charge the enemy. We advanced as far as our guard and the archers of the right wing of the [second] battle, in order to charge the enemy on our left, and we personally rallied and reorganized the squadrons which were dispirited and disordered. This done we attacked the said princes again, who were in considerable force of horse and foot, and they were broken and shattered. Many fled, about six or eight hundred horse towards Cologne. The rest stayed in great disorder in their camp. Our artillery continued to fire with such effect that it disrupted everything in their camp. Part of their infantry, up to two or three thousand of them, hoped to save themselves by boat, but a certain number were drowned. They threw their baggage into the boats in such a disorderly fashion that a good deal of it came floating down the Rhine, together with the dead and drowned, to the island were we had established part of our siege. It was then reported to us that the left wing and the reserves of the first battle, commanded by the count of Chimay, had beaten back the enemy in much disorder to their camp, so we decided to make all the formations advance to attack the [enemy] transport and, with this intention, we moved our artillery to where it could be most effectively used against the defenders of the said transport. But before this could be accomplished the light failed and night made it impossible for us to see everything, so that we could advance no further. By the grace of God we returned in such a way as to bring back everything safe and sound and at pur leisure, for it took us a good four hours to return to our siege. And, though their artillery fire was amazingly heavy and concentrated, nonetheless by the grace of God, our Lady and Monseigneur St. George, there were only three dead and six wounded among our people. |

*Death count appears to only account for notable deaths

A second account of the same battle.

| Quote: |

| On 23 May the Emperor with his army came and lodged nearer this lord [duke’s] camp, half a league from it, where he was below a hillock. At once the duke was happy and full of good cheer as it is possible to say, hoping to give battle to the enemy. He gave orders to those who had to defend the camp, so that the town remained besieged and so that certain places were furnished with men-at-arms to stop the enemy sallying forth. He ordered some conductieri with their men-at-arms to advance to a plain near, or rather next to, the camp, from which there was a bridge convenient to cross over. His lordship armed himself from head to foot in my presence joking with me the whole time. Armed, he went to the church near his pavilion to pray to our glorious Lady, then straight away mounted on a fine courser, he had some sixty big artillery pieces, bombards, spingarde and spingardelle, set forward in the above-mentioned plain while organizing the squadrons, the battle and the wings. … Then he made his troops cross the bridge en masse, in all about 12,000 picked combatants turned out like St. George. Certainly I never saw people so resolved either to die or to return victorious and advancing with such spirit, as these.

The duke laughed and seemed to be jubilant. He presented himself with these squadrons in front of the Emperor’s camp, which he found was already fortified with wagons and ditches with the [enemy] fully prepared behind the stockade, with much artillery. At about 20.00 hours the duke’s artillery and large spingarde began to fire among the enemy and they replied in terrible fashion so that it seemed like hell, and as if the world would be destroyed by thunder and fire. Then they attacked the leading squadrons with some infantry composed of hand-gunners but these were driven back and numbers of them were killed by our infantry. Afterwards a squadron of about 2,000 horse with many hand-gunners came out and, by command of the duke, Jacobo Galeoto and the count of Campobasso with the Italians assaulted them and drove them ignominiously behind the barricades. Then they reinforced themselves, so that 3,000 horse and about 6,000 hand-gunners on foot came out, their rear well protected by others. To bring them out further, Jacobo Galeoto and the count pretended to flee and, having gone some distance, they turned and pressed them so close that their horses passed over the bodies of many of their infantry, and again they drove them behind the barricades, killing a good many, with such impetus that many of our people penetrated inside. Here at the barriers the fight continued until dark night. … I was in the field during this engagement and I saw the duke applying himself in person here and there admirably in organizing and commanding. He has a mind like Caesar’s … I have never seen anyone so assured as his lordship. The [shots from] spingarde and bombards flew furiously around his horse, yet he did not care. … It required no small spirit to have left the siege and the fortified camp to go and assault the Emperor and all the power of Germany, which has not been so united for 200 years and to have returned with such a honour. |

Now having said all this my question boils down to this: Did these medieval generals arrange their army in a column like shape with successive lines of soldiers arranged deep rather than wide, or am I misinterpreting the text? And, provided the answer to the first question is yes, why did they arrange their army in such a manner? Was it a lack of space that left them unable to deploy their army in full width or is there some kind of tactical consideration?

Cheers!