Here is what Oakeshott wrote about these pommels in the Archeology of Weapons:

Type A. In use frequently between c. 980 and 1120. More rarely up to c. 1200 on Type X swords.

Type B. Development of A. Popular between c. 1150-1250 on swords of Types XI and XII.

Type C. Development of Viking Type IX pommel. Popular c. 980-1100 on Type X swords.

Type D. Development of C and used between c. 1230-1280, generally on Type XII swords, but occasionally on Type XIII.

Type E. Same as D, another variety. Excellent example in hand of one of the Benefactors of Naumburg Cathedral (Conrad).

Type N. A rare type, obviously a bye-form of A, characterized by extreme breadth. The only two actual examples are a large war-sword (Type XIII) in Zurich and another, even larger, in Bucharest, found in Rumania. One of the Naumburg benefactors (Wilhelm von Cam-burg, fig. 107) has one on a short sword of Type XIV.

(Oakeshott dates a long griped type N from Romania in the Records of the Medieval Sword to 1100+...)

Type O. Curiously enough, nearly every sword (and there are many) carded by carved warrior-figures in the Cathedral of Freiburg has a pommel of this unusual form. Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane (fig. 108), SS. George and Sebastian (these two have long-gripped war swords), on the West Front and one of the sleeping guards of the Holy Sepulchre. All these figures were made about 1300. There is one pommel of this sort in the Maciejowski Bible. The only actual example I know of is on a sword which was in the Gimbel collection earlier in this century.

Here are a few sentences from the Sword in the Age of Chivalry:

Perhaps the most widely used pommel during the three centuries between c. 950 and c. 1250 is that which is generally known as the Brazil-nut form. It is perhaps also the most widely misunderstood, and the most often mis-dated. Therefore it may be expedient to begin with a detailed analysis of its development and image, treating it with a thoroughness not necessary in the case of other types.

It has been generally assumed that pommels of this form were in use during a period extending roughly from 1150 to 1250. There is, however, ample evidence clearly datable iconographical evidence to show that swords were furnished with them 200 years before this period, and that their use was general throughout the 11th and 12th centuries, particularly in Germany.

There are two other current misconceptions about the Brazilnut pommel that it developed from the so-called "Mushroom" form and eventually superseded it, and that the extent of the upward curvature of its lower edge is an indication of development and so of date. It has been stated by many authorities, in rather vague terms, that the Brazil-nut began to develop from the Mushroom form early in the 12th century, and that during the next 150 years the curvature of its base steadily grew until by about 1230 the upper edge was straight. The evidence shows conclusively that this was not so; both forms developed simultaneously in the early to middle 10th century, if not before; all the different varieties of the Brazil-nut, with a greater or lesser degree of curvature to their bases, were in use at the same time, alongside the more familiar lobated types of Viking pommel, and the variations in its shape were probably the result of chance or personal taste and not a matter of date at all.

And a bit later:

...The Brazil-nut pommel, on the other hand, continued in use for another 150 years. In the mid-12th century it began to develop a greater bulk, and in the later years of the same century several derivative forms appeared. The original shape of the 10th century was never quite lost, but the later types are easily recognizable by their much more massive appearance.

...It is not until we examine swords and monuments of the second half of the 12th century that we begin to see any noticeable change in the shape of the Brazil-nut pommel; at about that time it seems to have increased in depth or thickness at the base, so that it appears more conical when seen in profile. At the end of the century its height also began to increase until it became more like a peanut than a Brazil-nut (plate 4B).

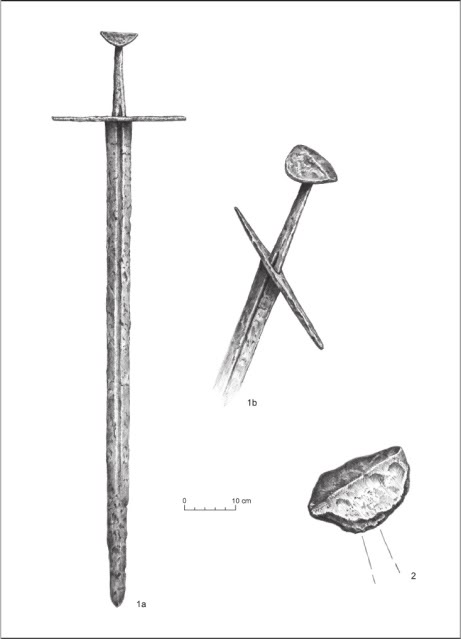

Than he gives this picture with a text:

Another, made by Rodkerus of Helmeshausen in 1118, gives us several portrayals of X-type pommels.9 In the scenes which decorate the panels forming the sides and ends of this altar (the martyrdom of Paul and the baptism and death of Cornelius) several swords appear; all of their pommels are of the two X-types. In a group of three swords we can see (fig. 50) the three basic styles of the Brazil-nut form together the semi-circular one with a straight upper edge, the wide shallow form with upper and lower edges curved equally, and the short stubby type. This group alone is evidence enough that the semi-circular style was not a late development but was contemporary with all the others, including the Tea-Cosy form. I think there is no doubt that the differences in the shapes of these pommels drawn by Rodkerus are deliberate, not accidental; his literal treatment of the weapons he portrays is shown by the inscriptions with which he has decorated some of their blades. These inscriptions are not in the form of names, as is the case with some other drawings of the same period, but of various apparently meaningless combinations of upright lines, crosses and circles, and in one case an interlaced pattern (figs. 51a and b).

And later:

The second half of the 11th century brings us to the time where the Brazil-nut pommel begins to assume its final form, well exemplified by the ''Sword of St. Maurice" in Vienna. Its particular interest lies in its great beauty of form, its restrained and simple decoration and its perfect condition; it seems to have been untouched by the hand of time (plate 5B).

About cocked pommels:

It does not seem to have been quite so widely popular as the two X-types, though it was in use all through the 11th and 12th centuries and its development was parallel to that of the Brazil-nut type that is, it became more massive towards the end of the 12th century and remained in use down to the end of the 13th (fig. 57). As a matter of fact we find representations of the final forms of this type at a later date than the last of the X-type.

About merging of brazil nuts and cocked pommels:

Many of the large, developed Brazil-nut pommels of the mid-13th century seem to be a fusion of the two types: the Brazil-nut form no longer very like a Brazil nut tends to develop a slight concavity on its upper edges. The sword of Count Konrad at Naumburg is like this (fig. 61), and so is the pommel of an identical sword in the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh whose finding-place is unfortunately not known (plate 12B).

In the Sword in the Age of Chivalry he also gives a slightly different datings and descriptions of his pommel types:

Type A.

A development of X, with the ends extended to form a very wide pommel, often as much as about 4" across. The earliest datable examples, clearly shown, are from an Arpad grave-find in Hungary of c. 1000, and a drawing (see fig. 8, p. 30 above) in an Ottonian manuscript picture datable between 98399.30 It probably remained popular until c. 1150 (plates 2A and 4C).

Type B.

This is bulkier and shorter and rounder than A, being a stouter version of X. Never very common, it seems mostly to be found on swords which on other evidence, i.e. blade inscriptions, can be dated between c. 1050 and c. 1150 (plate 4B).

Type C.

The pommel found on Viking swords of Type IX, like a cocked hat (Petersen's Type Y)31 is the immediate ancestor of C, which is of a similar hat-shape, but taller in the "crown" and now made in one piece (fig. 59). It is shown in art up to about 1150, merging after that time with:

Type D.

A stouter, bulkier version of C. Most frequently found in painting and sculpture between c. 1225 and c. 1275, and upon surviving swords which seem to be of the same date (see fig. 60, p. 90 above).

Type E.

Similar to D in bulk, it has straight or only slightly dished upper edges. Sometimes has a pronounced mid-rib (fig. 61). Contemporary with D (see plate 12B).

Type B1.

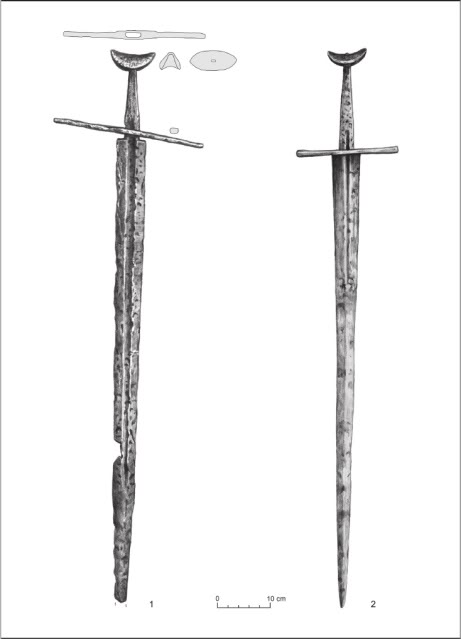

It bears some resemblance to the B pommels but with a straight lower edge. Good examples are in the Tower of London and the Historisches Museum in Berne (fig. 1).

Type N.

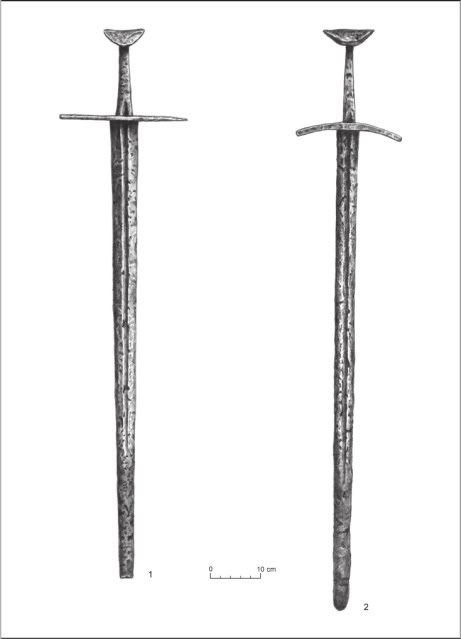

A pommel shaped like a boat. Examples are rare; there is one in the Zweizerische Landesmuseum in Zurich (Type XIIIa) and a second is in private hands in Rumania. This also is of Type XIIIa, a very large one. In art it is not quite so rare for instance, one of the Benefactors of Naumburg has one (Wilhelm von Camburg) on a short sword of Type XIV (see fig. 62, p. 92 above).

Type O.

Another rare type, but, curiously, nearly every sculptured figure of a military kind in the Cathedral of Freiburg has one of them. George and St. Sebastian, the sleeping guards at the Sepulchre, St. Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane and many more (figs. 65, 66, 67). Actual examples are almost unknown. There is a photograph of one in the catalogue of the Gimbel Collection. Even the never-failing Maciejowski Bible only shows one of them.

Now, I see some problems with his datings and classification. First, he gives different datings for different brazil nut types but at the same type says they were all contemporary and a matter of taste, not a date. Second, he has less different brazil nut types than Geibig and if Geibig has more precise dating for his types it could help to date some swords Oakeshott had problems dating. For example sword of St. Maurice in Turin has a type A pommel according to Oakeshott, but A type is Geibig's 15 and the pommels like on St. Maurice of Turin are 16v.II according to Geibig. Oakeshott wasn't sure for that sword, it might be early 12th as well as first half of 13th century according to him, but I think Geibig types could date it more securely since it has more detailed typology of such pommels.

Other problem is with the type N pommels. N family is rather limited sword family and they are probably made in a relatively short period, according to very good arguments from Marko Aleksić's article "Swords with pommels of type N", probably early 13th century. Oakeshott is obviously outdated about the dating of such swords since he guesses the type N sword from Romania in the Records of the Medieval sword to be about 1100 or a bit later... What does Geibig say about his type 17v.I which is Oakeshott's N?

Also he doesn't give any evolution theory for cocked hat pommel types.

So basically I would like people knowledgable about Geibig's typology and dating to post the dates of his types so that we could compare them to Oakeshott and see if we can maybe shed some light on the areas which are darker in Oakeshott's system. I only know about Geibig typology what can be read here on myArmoury featured article and that is not enough.

Also it would be great if people like Peter Johnsson and Craig Johnsson who have extensive experience with the originals could post some of their conclusions about these problems based on their research.

Any discussion, data or pictures on these types is welcome on this thread, it doesn't have to be Oakeshott / Geibig oriented.