I have documented LaTène swords these last few years in the quest for more detailed data. Little by little my respect for those smiths who made these blades have grown. It is obvious they were great creators and keepers of highly developed forging traditions. In roman times that region was called Noricum, famous for swords and high quality steel. It is interesting to note that the centre of the LaTène area also coincides with what later came to be Passau, the famous blade making centre of the middle ages. The mark of Passau blades was the running wolf, a mark that was pirated by the makers in Solingen in the 13th century. One can contemplate if Ulfberth (Ulf- meaning wolf) might have been working in the Passau region and not the solingen are as is often surmised. Please note: that is only speculation on my part: a favourite fantasy.

In most literature on the subject of celtic swords, you see some strange ideas continued. It seems the celtic sword is mostly described as having no point. Most blades I have seen do have an adequate point similar to those on mlater medieval blades. Those with blunt ends are in minority.

Another aspect that is striking is the skill with how the blades are forged and ground. Roman historians describing the short-coming of celtic swords when encountering roman legionaires must be seen in context: Celtic swords were probably not meant to be used on armoured opponents. The blades show a high degree of specialization: slim dimensions, fine and thin edges and points that can be used in slashing cuts and thrusting attacks on opponents that have none or very little in the way of armour. Quick, precise swords meant to be used by expert swordsment in single combat betewwn equals (or to be used in terrorizing unarmored civilians, of course). This is very different from trying to hack into a line of heavily armed infantry with sturdy helmets and metal reinforced shileds. A highly specialized tool is bound to fail when put to use in a way not intended with the design.

What would have happened if the highland scots were armed with small-swords instead of basket hilted broad swords? Would their charge have been as famous?

It is obvious they used a variety of iron alloys and steel to make most of the available material, yet it seems when analyzing surviving blades, that heat treating the steel was not very common. This is very strange, and I cannot help wondering about what methods and samples have been used to arrive at these conclusions.

If I may again speculate, it may be that corrosion and ritual "killing" of swords by annealing could be the cause for the results showing only marginal or no heat treat. If the steel is low in carbon content and has a fine structure, we will only get a thin layer of hardened steel in the thinnest portions of the blade. This is also the parts that are most subject to corrosion. If the sections chosen for analyze is taken from a part of the blade closer to the hilt (where there is more healthy material left from corrosion) it would only be natural to find a lower amount of heat treat here. The point area would have had the higest hardness and as this is also the thinnest part of the blade, any corrosion here can have a big inpact on the results of metalurgical analysis.

Testing of bronze age swords sacrificed in english lakes and rivers have shown that many were annealed before being thrown into the water. Annealed, but not bent! If bronze age smiths/swordowners knew about the damaging effects of applying heat to a fine blade, then surely it would have been known during the celtic iron age, one would think? Many steel blades show a fine pearlitic structure (unhardened = soft) which is exaclty what would have been the result if a blade was placed on hot glowing embers (a funerary pyre?) untill dull red and left to cool. This process would erase all previous traces of heat treat.

We cannot know if any of these my ideas are true. I have not made research of my own to support thisin a scientific way. Still, I cannot help but wonder if we won´t see new facts emerging in the future that will shed new light on the metallurgical refinement of LaTène period swords...

Their structure and fine dimensions make it hard to believe no heat treating was used to make the thin edges harder and the slim spines more springy.

Apart from the blades, the scabbards are also very skillfully made and show a great ingenuity in design, decoration and construction.

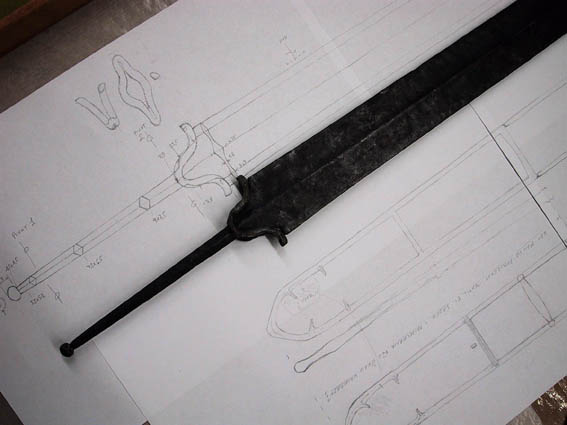

what material I have collected is too small to show something other than a selection of various possibilities. I gather information to base reconstructions on and to use as inspiration in designing swords. It is very different from the work done by an historian or archaeologist, who must look at the whole range of surviving material to draw conclusions. I can pick and choose those that I find interesting and inspiring. With that in mind the pictures might still be good illustrations of the variations of the LaTène sword.

It would be great if others would like to comment and/or add material of their own to illustrate this topic.

A very poor photo of a famous sword in the British museum. It is arranged incorrectly, as the pommel and guard have changed places and are turned the wrong way. I like these hollow bronze grips, though. Perhaps you can get an idea of the shape despite the poor quality of the photo :