How long could the length of swords with blades made out of either copper or bronze reach :?:

I have a chart from the book called "The Encyclopedia of the Sword" and "supposably" these blade lengths from the ancient or classical world are correct and I was just wondering if these blade lengths are accurate?

Egyptian sword blade: 17 to 36 inches

Etruscan sword blade: 14 to 25 inches

Greek sword blade: 14 to 25 inches

Roman sword blade: 19 to 27 inches

Jewish sword blade: 18 inches

Well, for starters, copper wasn't used for sword blades--swords weren't invented until the Bronze Age. Minor point, probably, since older sources often use "copper", "bronze", or even "brass" almost interchangeably, whereas modern scholars tend to play it safe by saying "copper alloy" unless they KNOW the allow in question!

Bronze blades from most cultures tended to run in the "short sword" length, from knife length up to 24 inches or so. But not all of them!! There are "rapiers" from the Mycenaean Shaft Graves that are easily 3 feet long, and they appear to be fully functional. Some late Bronze Age Mindelheim swords from Europe are almost 3 feet long, as well, if I'm remembering correctly.

Couldn't tell you about the specifics of Egyptian swords, those aren't my area. Interesting that the list is so specific about Jewish blades, since from what I can tell NO one is sure what the Hebrews were using in the Bronze Age! And not much point in listing the Romans, since they used iron and steel for swords--they were well past the Bronze Age. (Those lengths would be more like 16 to 32 inches, anyway!) "Greek" spans both Bronze and Iron Ages, of course, so better to use the term "Mycenaean" for the earlier stuff.

Does that help? Vale,

Matthew

Bronze blades from most cultures tended to run in the "short sword" length, from knife length up to 24 inches or so. But not all of them!! There are "rapiers" from the Mycenaean Shaft Graves that are easily 3 feet long, and they appear to be fully functional. Some late Bronze Age Mindelheim swords from Europe are almost 3 feet long, as well, if I'm remembering correctly.

Couldn't tell you about the specifics of Egyptian swords, those aren't my area. Interesting that the list is so specific about Jewish blades, since from what I can tell NO one is sure what the Hebrews were using in the Bronze Age! And not much point in listing the Romans, since they used iron and steel for swords--they were well past the Bronze Age. (Those lengths would be more like 16 to 32 inches, anyway!) "Greek" spans both Bronze and Iron Ages, of course, so better to use the term "Mycenaean" for the earlier stuff.

Does that help? Vale,

Matthew

| Quote: |

| Well, for starters, copper wasn't used for sword blades--swords weren't invented until the Bronze Age. |

Ah, there's where I have to correct you :) There were indeed copper swords. Most were short, dirk sized. But there are exceptions, like this monster:

http://1501bc.com/page/british_museum_2006/09140101.jpg

It's from the middle-east (Beth Dagan, whereever that may be), and dates to around 2400-2000BC. It's almost pure copper, with a little arsenic. The blade is around a meter in length (or even longer)! I've seen an image somewhere of a group of warriors with exactly those swords, so they're not just for show either.

As for how long bronze swords could reach, the longest I know are the Qin period two handed swords from China. The longest is 111cm long, which would make 44 inches:

http://thomaschen.freewebspace.com/custom4.html

Interesting and thanks for the info!

One other question about Copper or Bronze swords wasn't it a challenge to keep a sharp edge, because in one of my books it says that it was difficult for a blacksmith/swordsmith to give either metals a sharp edge and keep it from going dull with usage? :confused:

One other question about Copper or Bronze swords wasn't it a challenge to keep a sharp edge, because in one of my books it says that it was difficult for a blacksmith/swordsmith to give either metals a sharp edge and keep it from going dull with usage? :confused:

| Matthew Amt wrote: |

| There are "rapiers" from the Mycenaean Shaft Graves that are easily 3 feet long, and they appear to be fully functional. |

These have been identified as being imports of Late Minoan manufacture from Crete, the Minoans being the leaders in bronze technology throughout the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean regions. The earliest example of these "rapiers", dating to the Middle Minoan period, about 1500 BC , was excavated at the palace complex at Mallia and was, like all of the Type A and B Minoan swords found on Crete, unearthed in a ritual context. This, along with the relatively fragile riveted handle/tangless blade juncture of the swords, and a complete absence of any representations of combat between humans in Middle Minoan iconography, is taken as evidence that these early swords were intended as ritual paraphrenalia rather than actual offensive weapons. Most if not all measure approximately 3 feet in length.

| Jeroen Zuiderwijk wrote: |

| Ah, there's where I have to correct you |

Ha, thanks Jeroen, I knew I could count on you! Usually I remember not to be so absolute!

| Quote: |

| swords wasn't it a challenge to keep a sharp edge, because in one of my books it says that it was difficult for a blacksmith/swordsmith to give either metals a sharp edge and keep it from going dull with usage? |

Well, they're easy enough to sharpen. Generally the edge was hammered to work-harden the metal, and then some work with a whetstone would make it sharp. Since good tin bronze is harder than wrought iron, you could certainly get a decent edge. Straight copper is definitely softer, just don't mistake it for clay or something, eh? How long it stays sharp is more a matter of how much abuse it gets, I guess--probably a kitchen knife does a lot more cutting in the average month than any sword!

| Quote: |

| These have been identified as being imports of Late Minoan manufacture from Crete, the Minoans being the leaders in bronze technology throughout the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean regions. The earliest example of these "rapiers", dating to the Middle Minoan period, about 1500 BC , was excavated at the palace complex at Mallia and was, like all of the Type A and B Minoan swords found on Crete, unearthed in a ritual context. This, along with the relatively fragile riveted handle/tangless blade juncture of the swords, and a complete absence of any representations of combat between humans in Middle Minoan iconography, is taken as evidence that these early swords were intended as ritual paraphrenalia rather than actual offensive weapons. |

I'm very weak on the Shaft Grave era, but I hadn't run across this import theory before. True, MOST of Mycenaean culture was credited to the Minoans at some point or other. From what I've heard of those swords, however, many of them were very functional. The later ones had very sturdy handles and often had marble pommels, making a good balance. Even on the earlier ones, the hilt joint was not necessarily as "fragile" as we've been led to believe, particularly since these are mainly thrusting weapons. I also find it curious that those peaceful Minoans seem to have used so many weapons in their rituals! Part of that could just be me being cynical, of course, but over the years I've seen EVERY piece of Bronze Age armor or weaponry written off as "ceremonial" by someone, so I tend to be skeptical.

Khairete,

Matthew

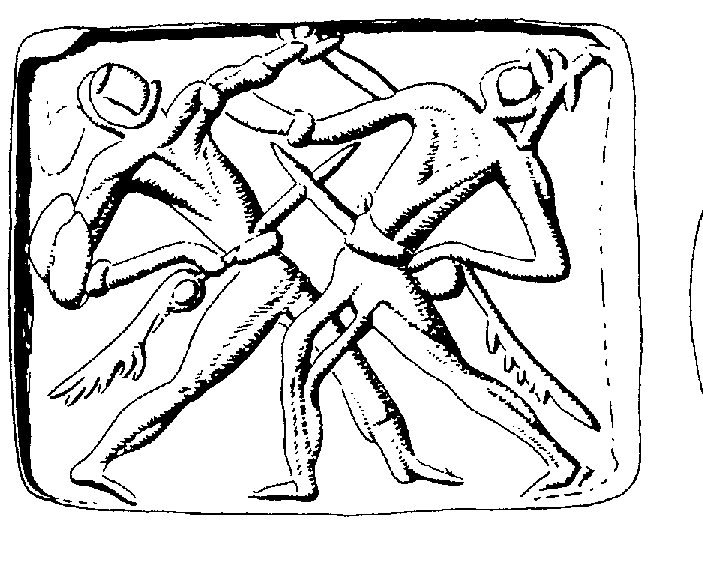

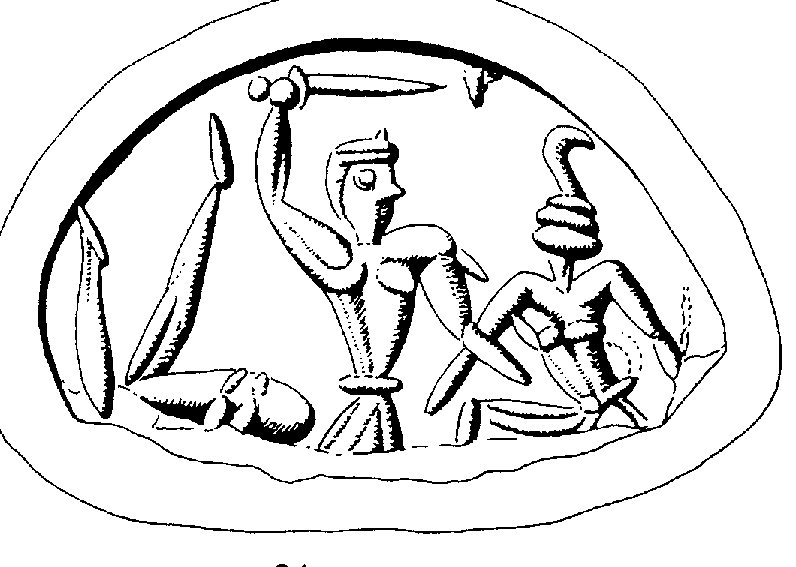

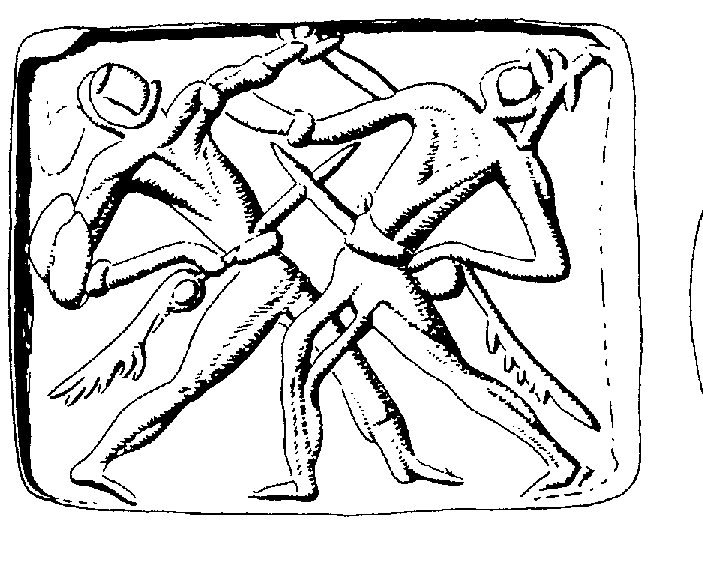

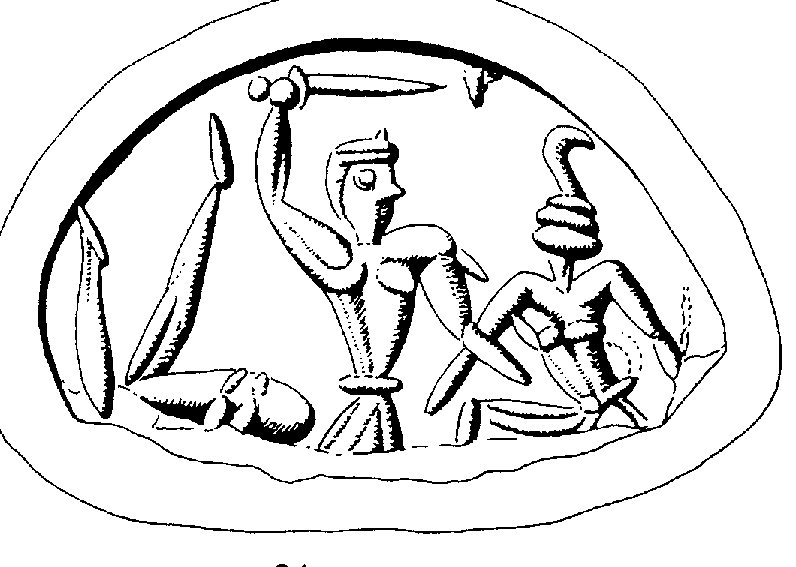

There are quite a few repreentations in early greek art of these long thrusting swords being used in fighting and even battle. Some situations could be duels between heros perhaps in a ritualistic situation, but other clearly depict a battle scene with fallen warriors at the feet of other combatants.

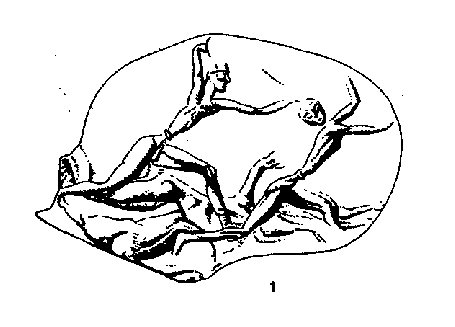

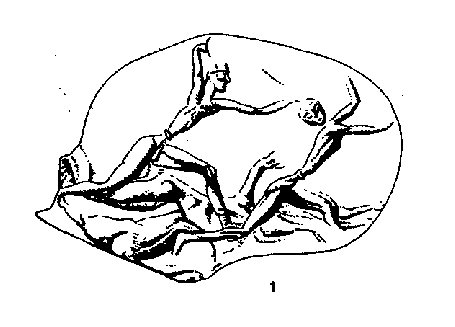

Attached are examples of seals from the book "Die Schwerter in Griechenland..." by Imma Killian-Dirlmeier

(I wonder if the top one is showing a strange combination of football and fencing?)

The seeming fragility of the mounting of these blades would much depend on how they were used. I am not convinced that sword were being produced with the only intention of being ritual or status objects. It might be that the sword had a limited role on the battle field, but that would be true for many historical periods. It is most a strategic and tactical problem, not so much a question of sword construction or metallurgy.

A sword can be made sharp enough for long enough to take the lives of several opponents and save the life of its owner a few times around even if it is made in bronze. The relative fragility or sturdiness of any tool much depend on the knowledge, skill and experience of the user.

I think that too much has been made of the shortcoming of early swords: looking for a technical or metallurgical reason for development to iron based manufacture.

I think the reason can be found elsewhere. It might be a matter of economy and/or politic as much as anything else.

I am not convinced there is a clear superiority of steely iron over bronze if compared for sturdiness or sharpess side by side.

If we add trade, control of economy, availability (or lack of) of local rescouces to the picture, other reasons might emerge.

I have a strong suspicion that the splendid Mycean rapiers are not made just for show, but are deadly and serious weapons in the hands of a skilled user.

Attachment: 63.18 KB

Attachment: 63.18 KB

Attachment: 71.88 KB

Attachment: 71.88 KB

Attachment: 106.07 KB

Attachment: 106.07 KB

Attachment: 91.76 KB

Attachment: 91.76 KB

Attachment: 112.32 KB

Attachment: 112.32 KB

Attachment: 65.45 KB

Attachment: 65.45 KB

Attached are examples of seals from the book "Die Schwerter in Griechenland..." by Imma Killian-Dirlmeier

(I wonder if the top one is showing a strange combination of football and fencing?)

The seeming fragility of the mounting of these blades would much depend on how they were used. I am not convinced that sword were being produced with the only intention of being ritual or status objects. It might be that the sword had a limited role on the battle field, but that would be true for many historical periods. It is most a strategic and tactical problem, not so much a question of sword construction or metallurgy.

A sword can be made sharp enough for long enough to take the lives of several opponents and save the life of its owner a few times around even if it is made in bronze. The relative fragility or sturdiness of any tool much depend on the knowledge, skill and experience of the user.

I think that too much has been made of the shortcoming of early swords: looking for a technical or metallurgical reason for development to iron based manufacture.

I think the reason can be found elsewhere. It might be a matter of economy and/or politic as much as anything else.

I am not convinced there is a clear superiority of steely iron over bronze if compared for sturdiness or sharpess side by side.

If we add trade, control of economy, availability (or lack of) of local rescouces to the picture, other reasons might emerge.

I have a strong suspicion that the splendid Mycean rapiers are not made just for show, but are deadly and serious weapons in the hands of a skilled user.

Last edited by Peter Johnsson on Thu 01 Feb, 2007 1:41 pm; edited 2 times in total

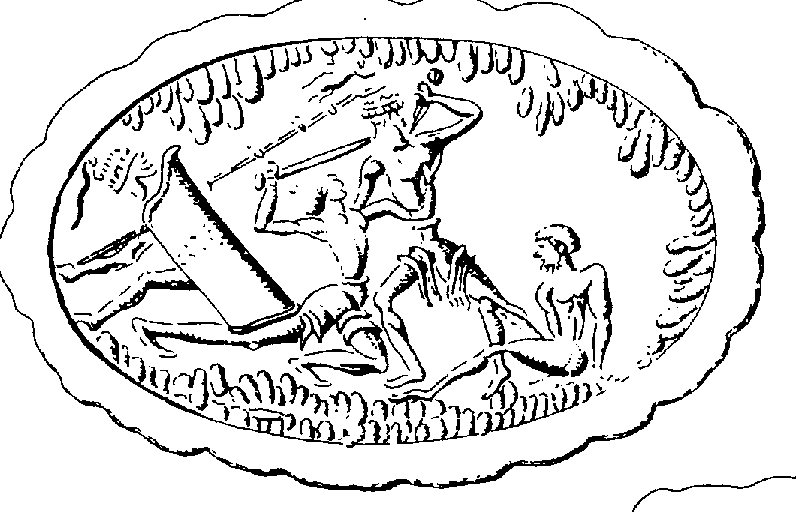

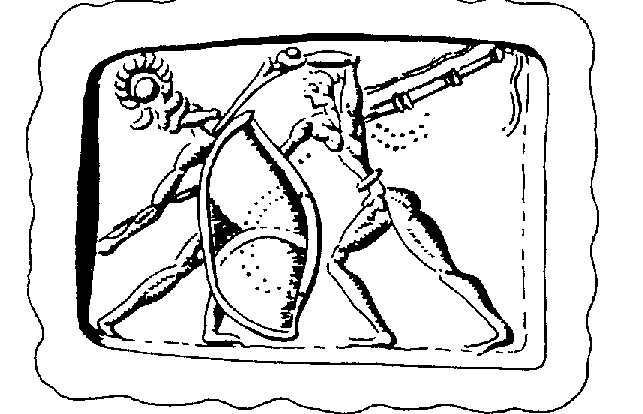

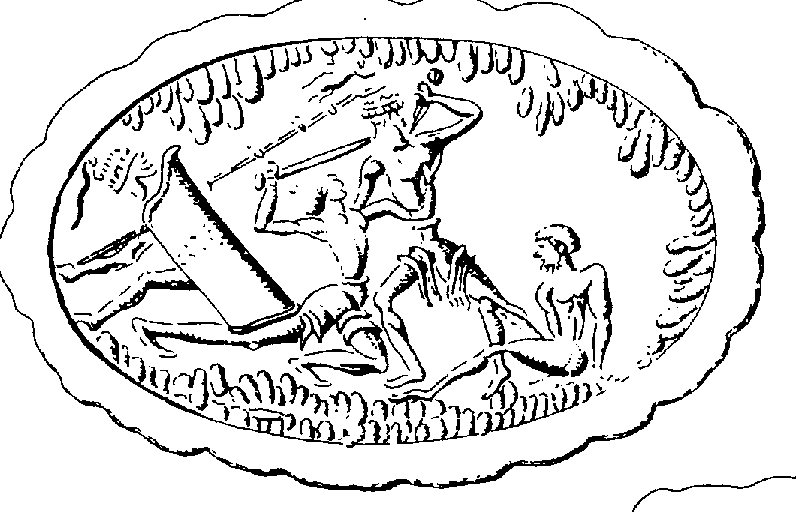

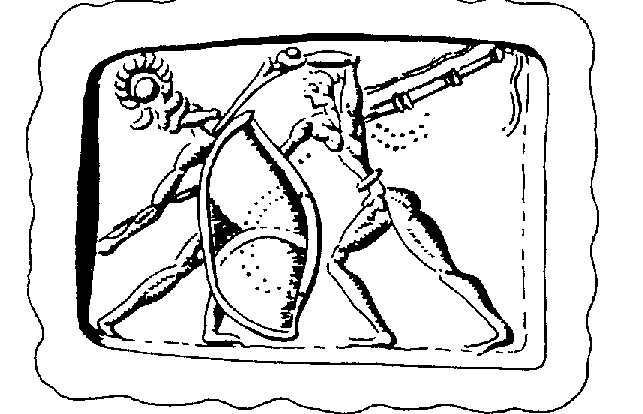

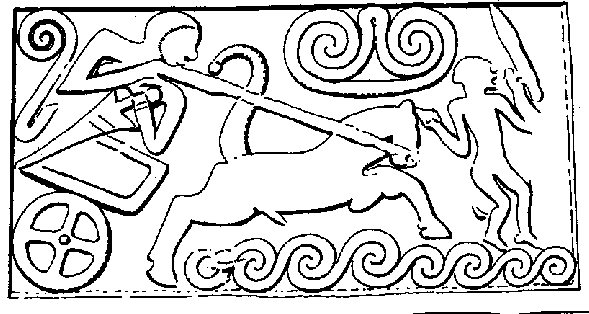

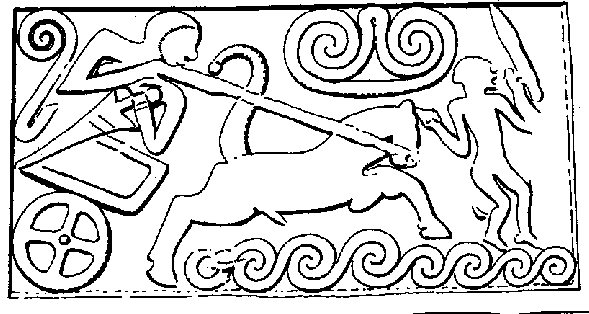

And a few more...

Note how a thrust from above seems to be a popular technique: the swordsman seems to aim at the base of the throat or behind the collarbone of his opponent, often above the rim of his shield.

The sword is held in a ice pick or hammer grip, it seems. Short grips and wide pommels would make such a grip secure, much like the tight grip of ater era rondell daggers.

The top one of these last two is rather gruesome: a battle frenzied swordsman leaps over heaps of bodies, grasping his opponent by the hair, wrenchng his head back, while aiming the deathblow.

Note how the chariot warrior below is armed with a long thrusting sword as well as his primary weapon: the lance. He seems to be persuing his enemy into the sea.

Attachment: 30.63 KB

Attachment: 30.63 KB

Attachment: 71.43 KB

Attachment: 71.43 KB

Note how a thrust from above seems to be a popular technique: the swordsman seems to aim at the base of the throat or behind the collarbone of his opponent, often above the rim of his shield.

The sword is held in a ice pick or hammer grip, it seems. Short grips and wide pommels would make such a grip secure, much like the tight grip of ater era rondell daggers.

The top one of these last two is rather gruesome: a battle frenzied swordsman leaps over heaps of bodies, grasping his opponent by the hair, wrenchng his head back, while aiming the deathblow.

Note how the chariot warrior below is armed with a long thrusting sword as well as his primary weapon: the lance. He seems to be persuing his enemy into the sea.

| Justin Pasternak wrote: |

| Interesting and thanks for the info!

One other question about Copper or Bronze swords wasn't it a challenge to keep a sharp edge, because in one of my books it says that it was difficult for a blacksmith/swordsmith to give either metals a sharp edge and keep it from going dull with usage? :confused: |

| Matthew Amt wrote: |

| Straight copper is definitely softer, just don't mistake it for clay or something, eh? |

Also mind that even pure copper can be workhardened quite far, harder then cast bronze. Considering only the edges were workhardened on swords, if you harden the entire blade of a copper sword it can be a close match to a bronze one (except for the edges being more susceptible to damage).

Peter, may I highly thank you for those images! I've been looking for quite some time for good pictures of European bronze age sword fights. These are excellent! Do you have more information about them? Regarding the last one, isn't the charriot driver just holding the leash, instead of it being a spear? Something else that strikes me, non of the sword bearers uses a shield! I've always had the assumption that sword and shield in the bronze age were linked. But it seems only the spear bearers have shields here.

My opinion whether swords or other weapons are ceremonial or not I usually determine by the design features. If the sword has design features that are purely there to make it function as sword, it has to be functional. F.e. the long rapiers mentioned have very thick midribs, in order to prevent bending of these long blades. This is purely there because they are so long, and wouldn't work well without it. There are swords that I know are definately ceremonial. These are the Ploughrescant-Ommerschans type, found in the Netherlands, France and the UK. These are up to 2.6kg swords, or basically highly enlarged versions of daggers, which are all left unsharpend, and don't have rivet holes to attach them to hilts. Also, one of these swords was deposited several centuries after it was made, showing that it was something very important, which was held on to for a very long time. There are more such examples of ceremonial "weapons". They're always they are based on actual weapons, which are very functional.

My opinion whether swords or other weapons are ceremonial or not I usually determine by the design features. If the sword has design features that are purely there to make it function as sword, it has to be functional. F.e. the long rapiers mentioned have very thick midribs, in order to prevent bending of these long blades. This is purely there because they are so long, and wouldn't work well without it. There are swords that I know are definately ceremonial. These are the Ploughrescant-Ommerschans type, found in the Netherlands, France and the UK. These are up to 2.6kg swords, or basically highly enlarged versions of daggers, which are all left unsharpend, and don't have rivet holes to attach them to hilts. Also, one of these swords was deposited several centuries after it was made, showing that it was something very important, which was held on to for a very long time. There are more such examples of ceremonial "weapons". They're always they are based on actual weapons, which are very functional.

| Jeroen Zuiderwijk wrote: |

| ....It's edge damage and resistance to bending where the hardness starts playing a role. This influences the thickness of the edge and cross-section of the blade to give the best robustness/sharpness compromise. Bronze age swords can bend, however the cutting edges were quite robust. As bronze workhardens fast when it deforms, cuts into the cutting edge don't go deep (2-3 mm for a Ewart Park sword) by f.e. edge on edge blocking. Also to keep in mind is that bronze when workhardened was close in hardness to the bulk of iron swords up to the early medieval period, which were often made from wrought iron, or unhardened low carbon steel. |

Yes, and this is with a concept that swordsmen of the bronze age used their swords for blocking incoming attacks.

One would think there are other ways to manage offensive and defensive manouvers.

Traces of use in battle would be less a matter of nicks and more about resharpening, I would suspect.

-there has been a study of resharpening of bronze swords by a Danish scholar. His name escapes me and I have sadly not read his work (only heard it referred to: many swords show a lot of traces from resharpening!).

-Jeroen, Matthew: do you know the work I am fishing for and have you read this? any one else?

I have done some limited experiments with bronze and found edges to be surprisingly sharp and resilient. Jeroen has done this rather thoroughly with quite authentic techniques as well.

With one of my bronze swords I could quite easily chop a 2"X4" pine plank in two (with several chops naturally) without any dulling or damage to the blade. The edge was not quite hair popping sharp to begin with, but it clearly had a good bite to it and gave a smooth surface in the cut.

Even if the blade sometimes got a slight bend after a badly placed cut or if I struck a very resilient and unyielding target, it was no great trouble to straighten it again.

After these rather preliminary tests I have gained a greater respect for bronze weapons. I look forward to an opportunity to making them, but sadly very few would be prepared to pay the price for such a sword. (It takes more work to do a bronze sword than a similar one in steel; at least for me).

Below is a snapshot of the sword I used for cutting planks. It is 64 cm overall with a blade length of 54 cm. As you see I have not mounted a grip on it. The bare blade weighs 580 grams. The cardboard tube is 2" diameter with a wall thickness of 3 mm. The cut was executed with the tube standing on the floor without support.

Last edited by Peter Johnsson on Thu 01 Feb, 2007 2:47 pm; edited 4 times in total

| Jeroen Zuiderwijk wrote: |

| Peter, may I highly thank you for those images! I've been looking for quite some time for good pictures of European bronze age sword fights. These are excellent! Do you have more information about them? Regarding the last one, isn't the charriot driver just holding the leash, instead of it being a spear? Something else that strikes me, non of the sword bearers uses a shield! I've always had the assumption that sword and shield in the bronze age were linked. But it seems only the spear bearers have shields here.

My opinion whether swords or other weapons are ceremonial or not I usually determine by the design features. If the sword has design features that are purely there to make it function as sword, it has to be functional. F.e. the long rapiers mentioned have very thick midribs, in order to prevent bending of these long blades. This is purely there because they are so long, and wouldn't work well without it. There are swords that I know are definately ceremonial. These are the Ploughrescant-Ommerschans type, found in the Netherlands, France and the UK. These are up to 2.6kg swords, or basically highly enlarged versions of daggers, which are all left unsharpend, and don't have rivet holes to attach them to hilts. Also, one of these swords was deposited several centuries after it was made, showing that it was something very important, which was held on to for a very long time. There are more such examples of ceremonial "weapons". They're always they are based on actual weapons, which are very functional. |

Jeroen, you are most welcome!

I sadly do not have precise info on these images. I had to select parts of the book when I copied it and I chose to have the pictures, rather than the text. All are from the same book, however. The fight scenes are printed in the back and all does have a povinence in the catalogue, if I remember correctly.

"Die Schwerter in Griechenland..." by Imma Killian-Dirlmeier is a splendid book. I tought you had it (or had it copied ;)?)

I agree with you on the way to make a distinction between functional and ceremonial weapons. Even those that are very rich and ornamented can be functional and in some way intended for actual use (at least as much as their less embelished siblings). I would think it is more a question if the owner were first in line or had others doing the fighting for him. The sword of the general or king could be as functional as the ones his soldiers carried, even if he does not do much practical fighting himself. For the situation when he *does* get into a tight spot I would think he would have had the best swordsmith make him the best and most good looking sword to be had....

On the chariot driver: you might well be correct!

I saw it as the spear, but it migh very well be the leash to the horses mouth.

-Perhaps it is a spear, though?:confused:

-Or perhaps he has lost his spear and run out of arrows and now simply want to run over or drown the poor guy in front of him....? :cool:

| Matthew Amt wrote: |

| I'm very weak on the Shaft Grave era, but I hadn't run across this import theory before. True, MOST of Mycenaean culture was credited to the Minoans at some point or other. From what I've heard of those swords, however, many of them were very functional. The later ones had very sturdy handles and often had marble pommels, making a good balance. Even on the earlier ones, the hilt joint was not necessarily as "fragile" as we've been led to believe, particularly since these are mainly thrusting weapons. I also find it curious that those peaceful Minoans seem to have used so many weapons in their rituals! Part of that could just be me being cynical, of course, but over the years I've seen EVERY piece of Bronze Age armor or weaponry written off as "ceremonial" by someone, so I tend to be skeptical.

Khairete, Matthew |

First off, the Mycenaeans were not descendants but usurpers of Minoan civilization at a time when the Minoan infrastructure had been critically weakened, most probably by a long series of natural catastrophes. One of their primary interests in dominating Late Minoan society was to exploit their superior bronze working technology for the manufacture of arms. Secondly, my statement comes from a point of evidence, in the form of a clear lack of evidence to the contrary. All of the Type A and B swords found on Crete were found in ritual contexts, ie.the Mallia Palace cult shrine, the sacred cave at Arkalochori, etc. and date to the Middle Minoan period. Conjecture all you like, there is NO evidence that swords of these 2 types were used in combat between human beings, but rather as ritual paraphrenalia and/or votive offerings. There is NO iconography from the the Middle Minoan period depicting weapons in use against other humans, but rather for hunting animals.

Peter,

The seal impressions you've provided, while wonderful, are Late Minoan and Mycenaean and not Middle Minoan and do not depict the Type A and B "rapiers" I referred to. They are Type D and later, which were known to have had integrally cast handles. Let's not make the mistake of lumping Minoan and Greek cultures together, please.

(BTW, while I have your attention, I want to congratulate you on your development of the Albion Maestro Line Liechtenauer. I got mine in December and can't let go of it! Thanks!)

The seal impressions you've provided, while wonderful, are Late Minoan and Mycenaean and not Middle Minoan and do not depict the Type A and B "rapiers" I referred to. They are Type D and later, which were known to have had integrally cast handles. Let's not make the mistake of lumping Minoan and Greek cultures together, please.

(BTW, while I have your attention, I want to congratulate you on your development of the Albion Maestro Line Liechtenauer. I got mine in December and can't let go of it! Thanks!)

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| I sadly do not have precise info on these images. I had to select parts of the book when I copied it and I chose to have the pictures, rather than the text. All are from the same book, however. The fight scenes are printed in the back and all does have a povinence in the catalogue, if I remember correctly.

"Die Schwerter in Griechenland..." by Imma Killian-Dirlmeier is a splendid book. I tought you had it (or had it copied ;)?) |

Nope. I've got a few pages of it, but not all of it.

| Quote: |

| I agree with you on the way to make a distinction between functional and ceremonial weapons. Even those that are very rich and ornamented can be functional and in some way intended for actual use (at least as much as their less embelished siblings). I would think it is more a question if the owner were first in line or had others doing the fighting for him. The sword of the general or king could be as functional as the ones his soldiers carried, even if he does not do much practical fighting himself. For the situation when he *does* get into a tight spot I would think he would have had the best swordsmith make him the best and most good looking sword to be had.... |

Yup, agreed. The sword may have had more additional roles in a lot of cases then just a weapon, like a car nowadays isn't just a vehicle to get from A to B. They would have been status objects (making clear that the bearer is a chieftain/king when you see him f.e.), or used in ceremonial purposes etc. But just because it may be a totally pimped out sword, doesn't mean it's not meant to be used as a sword :)

That's a very nice sword you've made b.t.w.!

| Gene Davis wrote: |

| Peter,

The seal impressions you've provided, while wonderful, are Late Minoan and Mycenaean and not Middle Minoan and do not depict the Type A and B "rapiers" I referred to. They are Type D and later, which were known to have had integrally cast handles. Let's not make the mistake of lumping Minoan and Greek cultures together, please. (BTW, while I have your attention, I want to congratulate you on your development of the Albion Maestro Line Liechtenauer. I got mine in December and can't let go of it! Thanks!) |

Thanks forpointing this out!

They are indeed late bronze age images. It even says so at the bottom of the page! Sloppy of me not to notice! Some of the swords depicted have the same length as the earlier swords, but I was wrong to make assumptions, of course. Sorry about that.

To follow up on the ceremonial role of the earliest swords of typ A: why do you think the Sword developed from a non functional ceremonial object into a functional weapon, instead of the other way around? To me the idea that the sword was first a ceremonial attribute, only later to develop into an actual fighting weapon is very strange. I would very much like to learn why this is thought to be the case. Please elaborate on this!

Is the fact that swords are non existant in art reason enough to assume they were not intended for fighting, or are there additional reasons? Lack of nicks in the edges? Lack of resharpening? They sometimes seem to be bent as if having struck a solid target and do at times seem to have scars in their edges. I don´t know for sure, it is only an impression I have got from looking at these blades.

The assumed fragility of the mounting does not convince me: I do believe it is possible to make a functional sword with the same mounting method as the Swords type A. Functionality depends on how you use the sword.

Please understand I do not mean to be confrontational: I really would like to learn more about these swords: they fascinate me!

PS : I am very happy to hear you like the Liechtenauer!

DS

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| To follow up on the ceremonial role of the earliest swords of typ A: why do you think the Sword developed from a non functional ceremonial object into a functional weapon, instead of the other way around? To me the idea that the sword was first a ceremonial attribute, only later to develop into an actual fighting weapon is very strange. I would very much like to learn why this is thought to be the case. Please elaborate on this!

Is the fact that swords are non existant in art reason enough to assume they were not intended for fighting, or are there additional reasons? Lack of nicks in the edges? Lack of resharpening? They sometimes seem to be bent as if having struck a solid target and do at times seem to have scars in their edges. I don´t know for sure, it is only an impression I have got from looking at these blades. The assumed fragility of the mounting does not convince me: I do believe it is possible to make a functional sword with the same mounting method as the Swords type A. Functionality depends on how you use the sword. Please understand I do not mean to be confrontational: I really would like to learn more about these swords: they fascinate me! |

I can best explain by quoting a 2006 paper I wrote on the subject. (Sorry for the length, but you asked.)

"Of the Type-A sword N.K. Sandars wrote: “The A swords, sometimes over a meter long, had a fatal weakness in the hafting, a slender tang that is often found snapped, and would have left the swordsman unarmed, with a useless hilt in his hand.” (1963: 118). Presumably Sandars is referring to true Type-A swords found distributed mostly as grave-goods outside of Crete within the confines of the Peloponnese, and Cyclades (Sandars 1961: 25) to where they had been exported or otherwise transposed as prestige items. Those examples that show signs of breakage very likely were subjected to more rigorous applications than they were originally intended, for all the technical expertise that went into their manufacturing. Our concern is the earliest of these swords, found on their native Crete, and by contrast, most, if not all, in ritualistic rather than mortuary contexts. As will be shown, Minoan iconography supports their function as ritual paraphernalia.

"The earliest known example of the Type-A sword, nearly a meter long with a wide flat central rib, tentatively dated to MM I (Pendlebury, 1939, 1990: 118; Sandars, 1961: 180, Schoep, 2002: 124) was found in an assemblage of cult paraphernalia in a shrine room at Mallia Palace (Marinatos, 1993: 109). It is mounted with a gold-covered ivory handle surmounted by a rock-crystal pommel. The handle is attached to the blade by a straight row of rivets that run parallel to the blade’s width (fig1). It is in fact, the earliest known true sword in the Aegean region, its length and reinforcing rib being without precedence (Sandars, 1961: 19).

Two other Type-A swords were found at Mallia Palace as well, also within a religious context (Peatfield, 1999: 68-69; Schoep, 2002: 113, 120), and may be contemporaneous with the crystal-pommeled sword previously mentioned (Sandars, 1961: 19), though my sense is that morphologically they supersede it. Both had been hilted, but the fittings of only one survive and will be discussed in more detail.

The features that distinguish the earliest Type-A swords are as follows:

The cast bronze blade is of unprecedented length, in some examples exceeding one meter, but none more than 1.55 meters. The proximal end consists of rounded shoulders surmounted by a truncated tang. In plan the blade tapers distally to a spatulate point of varying acuity. A robust central reinforcing rib runs the full length of the blade on both dorsal and ventral faces. In cross section the ribs are normally rhomboid, but sometimes rounded (Sandars, 1961: 17). Handles were separate constructions devoid of projecting hand guards, made of perishable materials, sometimes covered in gold foil, and attached to the blade by rivets driven through perforations forming a triangular pattern, usually one or two in the tang and one on either shoulder. Fig. 2 shows these distinctive

components, while Fig. 2.3 is from Arkalochori Cave, and shows the lack of rivet perforations on the tang and blade shoulders, prompting the idea of its intention as a votive offering.

"The genesis of the Type-A sword from the copper Cretan dagger is evident from key similarities in general construction, namely the placement of the two handle-securing rivets on the blade shoulders, and the high-profile central rib. The extraordinary length of the Type-A, however, probably owes its development to influence from the Near East where attempts at long blades reached limited success due to their lack of reinforcing ribs (Sandars, 1961: 20). The Type-A then, may very likely represent an amalgam of Near Eastern and native Cretan technologies, from which was born the first true sword, unobtainable before the perfecting of bronze-working, impractical before the innovation of the central reinforcing ribs.

What is reasonably certain is that the Type A first appeared on Crete, and abruptly. The question is: To what purpose? As a weapon? Possibly, but if so, one of specialized, non-martial application given its inherent weakness of hilt attachment. As already noted, the riveted handle/blade juncture and truncated tang presented a tenuous solution for wielding a weapon of such weight and length (Peatfield, 1999: 69). Bronze swords of similar construction found throughout Southern and Western Europe display the results of using such swords in combat: broken tangs and rivet holes ripped through the edges of the blades’ shoulders. The natural inclination when using a sword in a combative engagement, especially in the midst of multiple enemies, is to swing it at the opponent in an attempt to cut or otherwise wound them with the edge. Thrusting, for which the Type-A sword was clearly designed, is a skill requiring flawless precision and timing (Oakeshott: 1960, 1996: 26). Was it carried as a symbol of prestige, then? Undoubtedly, in part at least, given the costliness of bronze and the high degree of metallurgical proficiency required to create a sword from it. Swords have always been symbolic of the privileged elite, both in terms of visible wealth, and in terms of holding sway over the life and death of the subservient classes. But why then make a sword so long, so robust if its intended function was merely to serve symbolically or ceremonially? Such “swords of state” existed throughout time, but by virtue of a usually gracile construction, elaborate decoration, and costly materials have always been regarded as non-functioning.

The strongest evidence for the function of the earliest Minoan Type-A sword of Crete points to an active ritualistic application (Peatfield, 1999: 69). Their provenience in religious contexts, coupled with iconographic clues, suggest they were not just ritualistic cult paraphernalia or priestly accoutrements, but active elements of Minoan ritual (Driessen, 1999:15). In fact, their very crafting may in itself have been regarded as a ritual action (Warren, 1988: 35). Even if the functioning Type-A sword (or swords) of Arkalochori Cave was part of a mundane palatial metal horde and not an actual ex voto, does not mean its making was not regarded as a sacred, or even magical activity. As Budd and Taylor state, “In non-literate societies, complex procedures are necessarily ritualized - a sequence of procedures that cannot be written down in a scientific manual must be committed to memory as a formulaic ‘spell’.” (1995: 139). Analogies can be drawn to the sacredness and ritual surrounding the art of sword-making in cultures all over the world. Why not then in Minoan Crete, a land and culture steeped in magic, religious ritual, and symbolism, and renowned for its metallurgical expertise? We may expand on this notion by reasoning that a ritual for which an apparatus is specifically made would be made more potent by the ritualization of the apparatus’s making and subsequent dedication. This is especially true for an object that either is offered to a divinity directly, or by which a sacrificial offering is delivered to the divinity, whether it be a libation bowl or a weapon.

"Beside context and morphology, perhaps the most telling evidence about the true function of early Type-A Minoan swords comes from iconography. Intuitively, images of swords should be found in depictions of warfare. Yet warfare is a theme conspicuously missing in Minoan art (Gates, 1999: 277). This, along with a seeming absence of fortifications and a scarcity of weapons in the archaeological record, has been long considered as evidence for what Sir Arthur Evans termed the Pax Minoica. However, more recent opinion sees the possibility of any land, regardless of time period or location, knowing centuries without strife to be implausible at best (Gates, 1999: 277). Another possibility is that, perhaps even for reasons of magical association, the Minoans prohibited the depiction of warfare (Ward, et al., 1970: 75) lest it become a reality, in effect, manifested by those depictions. Depictions of weapons and fighting do exist in Minoan art, however, mainly in scenes of hunting, individual combat between men, individual combat between men and animals, and sacrifice of both animals, and possibly humans found on seals and sealings (Gates, 1999: 278). The swords that are clearly recognizable as being as such tend to be the LM Type-B, distinguished by proximally-slanting horn-like projections on the blade shoulders. The MM Type-A, the focus of this paper, appears much more infrequently, but is usually identifiable by its rounded blade shoulders and large, spherical pommel stone. One of the clearest depictions of a Type-A is to be found on the carved serpentine “Chieftain Cup” from the MM III – LM I palace at Hagia Triada. Needless to say, the interpretation of the scene depicted on the cup is the subject of much debate (Koehl, 1986: 99-100), and it is not the aim of this paper to add fuel to a fire of controversy that has been smoldering since the cup was found. What is important to our discussion is that the carving features a youthful male figure holding what is undoubtedly a Type-A sword (fig. 3), and that the overall scene is generally interpreted as being ritualistic rather than militaristic (Koehl, 1986: 109; Marinatos, 1999: 217; 2006: personal communication). Behind the sword-bearing youth are three other male figures (fig. 4), each bearing a large object commonly believed to be an ox or bull hide, either the skins of bulls sacrificed in celebration of an initiatory experience (Koehl, 1986: 109), or the trophies of a successful hunt (Marinatos, 1999: 217; 2006: personal communication). The symbology of hunting in Minoan art is in itself yet another point where scholars are in disagreement. While some scholars interpret such scenes literally as an activity that validated the manliness of the participants, in other words, a Right of Passage, an act of bravery (Hiller commenting on Peatfield, Peatfield 1999: 74), others see hunting scenes as a metaphor for sacrifice (Marinatos, 1986: 42-43). It is my personal view that these two ideas are too intertwined to be considered separately. Hunting has always been ritualized, initiatory, and ultimately sacrificial. Hunters don special clothes, arm themselves and carry specialized equipment. They journey to places apart from their habitation to test their abilities, strength, and bravery against the forces of nature, and sometimes nature wins. Either way, the balance of sacrifice and reward must be maintained. That swords are featured in such scenes in Minoan art must logically point to their ritual significance as instruments of sacrifice. This possibility is further hinted at by scenes depicted on several seals and sealings which show swords either in use in combat against predatory animals (fig. 5), or as part of an assemblage of religious paraphernalia (fig. 6). Several others depict what are purported to be swords shown in ritual contexts, but in comparing them with depictions of clearly identifiable swords of both Type-A and B, I must conclude that they are more likely to be wood-hafted stone maces, used to stun sacrificial bulls before they were killed (Marinatos, 1986: 22). It is interesting to note that when swords are shown in use on Minoan seals and sealings that they are usually held horizontally or at a descending angle, over the wielder’s head, tip lowered, and either ready to deliver a killing thrust or in the act of delivery (Peatfield, 1999: 71). Is it merely coincidence that the modern torero, armed with a slim thrusting sword (estoque), assumes the same attitude before delivering the death blow to his adversary (Douglas, 1984: 254)? This is not to say that the Minoan Type-A sword was produced with the sacrificial killing of bulls in mind, only that the morphology of the Type-A, like the delicate estoque of the modern Spanish Bull-fighter, made it quite useless for any other active application, its symbolic status not withstanding. As Marinatos points out (personal communication, 2006), the famed Minoan “Bull-sports”, very likely concluded with the sacrifice of the bull, yet no known iconography directly depicts this being inflicted by a sword thrust. While her last observation is undoubtedly true, I must counter that at the same time, no known MM iconography depicts two men fighting with Type-A swords either. Such imagery belongs to the Late Bronze Age (Peatfield, 1999: 71), and when recognizable, the swords are of the more serviceable Type-B, or its antecedents.

One additional work of Minoan iconography must be mentioned, significant as it comes from a component of one of the very earliest Type-A swords: the gold “Acrobat” pommel (sometimes referred to as a “roundel”) from the MM I-MM II sword with preserved hilt found at the palace of Mallia, previously mentioned. The pommel is a flattened, circular disc, hollow in the center to fit it onto the proximal end of the sword’s gold-leafed ivory hilt (fig.7). Incised around the distal face of the pommel is an image of what is commonly believed to be an acrobat, his body contorted in the act of tumbling (Daniel, 1939: 162). By anyone’s reasoning this is an odd decoration for a weapon of war, or even individual combat. In a book specifically devoted to an explanation of the “Acrobat Sword”, and its companion, whose hilt was not preserved, the swords’ excavator, Fernand Chapouthier inferred that these swords may actually have been used in a ritualized acrobatic display (1938), perhaps a symbolic reenactment of the famed Minoan “Bull-leaping” sport, in which the swords substituted for bulls’ horns. Besides the evidence of extensive iconography, it is uncertain whether the “Bull-leaping sports” actually occurred as depicted. If they did, the risk involved undoubtedly incurred horrendous casualties (Ward, et al., 1970: 119-120). Given that, it is conceivable that some substitute, still risky, but more controllable, might have been implemented.

"As the evidence, both physical, iconographical, and inferential strongly suggests, the earliest of the Type-A swords that appeared on Minoan Crete were most likely created for ritualistic rather than martial applications. However, this is not to say that they were passive ornamental or symbolic objects. Rather, they appear to have been actively used as ritual implements, perhaps even exclusive cult paraphernalia related to the sacrifice of bulls. This can be corroborated by their proveniences within assemblages of other ritual items, and in religious contexts. The abruptness with which they appear in the archaeological record also points to this probability. Their dichotomous morphology of robust blade, achievable by only the most adept of bronze-working craftsmen, and weak hilt attachment makes their effectiveness in armed combat, especially against multiple opponents limited, if not highly doubtful. This fact is quite obvious from broken examples of Type-A swords that were exported from Crete to places where the original dynamic they were created for had probably changed, with potentially disastrous consequences. Also, there is the absence of evidence for warfare on Crete during MM II-LM I to consider. "

If your interested in reading the full paper send me a PM.

Hmm, it seems that in relation to the 'monster' sword that Jeroen brought up, no one has said anything about arsenic bronze, which is some of the earliest bronze known. True, its metallurgical properties are obscure; the only things I have read about it is that it will not work harden quite to the point a tin bronze will, but is more ductile.

| Quote: |

| Traces of use in battle would be less a matter of nicks and more about resharpening, I would suspect.

-there has been a study of resharpening of bronze swords by a Danish scholar. His name escapes me and I have sadly not read his work (only heard it referred to: many swords show a lot of traces from resharpening!). -Jeroen, Matthew: do you know the work I am fishing for and have you read this? any one else? |

I overlooked this bit. I haven't heard of this study, but I'd be interested in reading it should you manage to find it. I have heard if a british archeologist who is studying british swords on battle damage. She found that a great majority show battle damage. I find that quite remarkable, as I wouldn't have expected to see a whole lot of damage, even if they were saw a lot of combat!

Page 1 of 2

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum