A more recent look at alloy and hardness of some Merovingian Swords, spears & etc.

http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/jom/0508/Ehrenreich-0508.html

| Jared Smith wrote: |

| 1) Ores were exported in the form of ingots (often Wootz originating from India, but commonly known for being worked in Damascus.) Ores were also traded in iron-steel rods of varying quality. Some materials such as the Wootz had carbon content as high as 1.5% which is excellent for hard tool steel, but were not ideal for a spring temper which should be closer to 1% carbon than 1.5%. This was taking place in "B.C." era. |

| Kirk Lee Spencer wrote: |

| Hi again...

One thing I noticed with Tylecote's work is that there should be a distinction between the act of pattern welding of the core, which gets all the attention and the amazing inclusion of high carbon steel for the edges which gets very little attention. While it may be that the layers of the Pattern-Welded core do not necessarily make for a better sword (only prettier), the high carbon steel edges certainly would add to its cutting quality. |

Well, the general idea I get is that the smiths tried to create a harder edge, and a tougher core. The latter can be done in various ways, one of which is by creating nice looking torsion damast. While the patterns may be decorative, and the same effect could have been achieved by other methods, that doesn't mean the patternwelding was only decorative.

| Quote: |

| Also notice that the use of phosphorus iron would explain why the swords Tylecote examined showed signs or workhardening... I have heard that phosphorus iron can be work hardened like bronze.

ks |

Hi Jeroen...

Sorry if I gave the idea that I believed pattern-welding was only decorative or even mostly decorative. In my post above I was trying to give some expert opinions which would be much more meaningful than my on feelings.

My own personal feelings on the matter (for whatever that may be worth compared to Tylecote's and Gilmore's work) is that in many cases, in their original state before over a thousand years of aging and corrosion, many if not most of these pattern-welded core blades did have a noticable increase in toughness and resilience. As I mention earlier, I think this is why it became a hallmark of relative superiority and was included as inlay and veneers in the twilight of medieval pattern welding.

What I really wanted to emphasize in the above post, is that, to me, it is more amazing that these dark age swordsmiths could forge such fine and thin layers of steel into the edge of the blades for the full length of a 30 inch blade than that they could forge weld a bundle of twisted billets together in the core. Also I wanted to suggests that even if we were to accept the most extreme view that pattern welding was only decorative then, in terms of superiority, we still must deal with the issue of these welded on edges and especially the layered sandwich type edges with high carbon steel cores. Who is going to say that this is only decorative? It is clear to me that this was obviously meant to be functional and the experts seem to agree on this point. So... If we were to ask if there was a natural superiority in function with these pattern welded prestige weapons the answer would be yes, even if the patterns were only "bling bling." :D

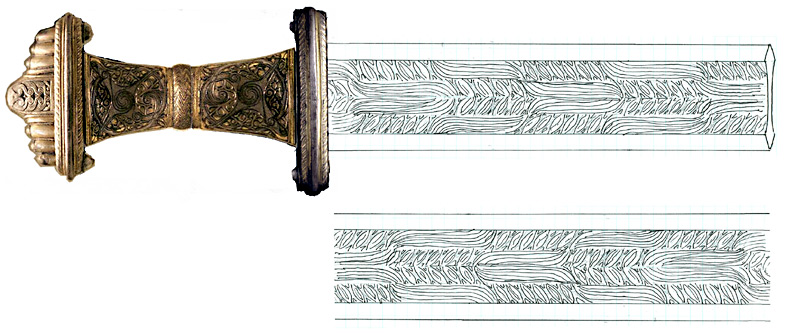

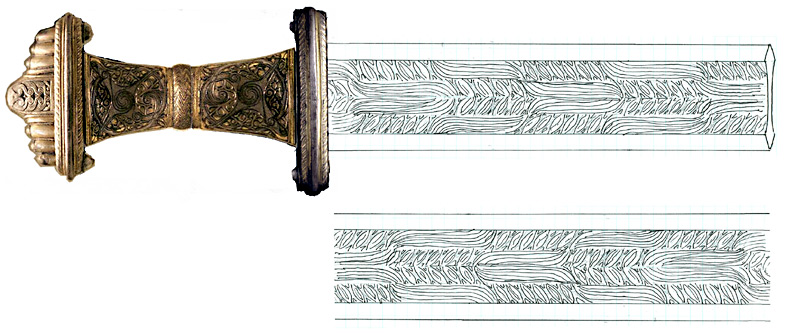

Great point... And to add to it (and probably open another can of worms): The very fact that they are experimenting with so many "various ways" and patterns in the core would suggest that they are trying to increase some functional aspect. If someone countered that the variety was simply the ever increasing desire for the "new" in decoration then, in IMHO, they don't understand the ancient mind. The obsessive "quest for the new" is a modern condition. The ancients were much more conservative. They believed, and I say this in very general terms, that old was good (tested and proven) and new was bad (unproven and chancy)... just the opposite of the modern tendency. That would explain why decorative trends, as well as technological status quo existed for centuries or longer. For instance with pattern-welding designs, it may look as if they had tried every pattern that could be imagined. However there seems to be some patterns that have not been found as of yet but would have a really nice look. As a matter of fact it was on of these patterns I really liked when designing the reconstruction of the Fetter Lane sword. It involves billets side-by-side twisted in the same direction and offset on each side of the core. I will try to post an image.

It gives a very nice decorative effect but was so unperiod that Barta reversed the outer billets to be more in keeping with period patterns.

take care

ks

Attachment: 94.45 KB

Attachment: 94.45 KB

Sorry if I gave the idea that I believed pattern-welding was only decorative or even mostly decorative. In my post above I was trying to give some expert opinions which would be much more meaningful than my on feelings.

My own personal feelings on the matter (for whatever that may be worth compared to Tylecote's and Gilmore's work) is that in many cases, in their original state before over a thousand years of aging and corrosion, many if not most of these pattern-welded core blades did have a noticable increase in toughness and resilience. As I mention earlier, I think this is why it became a hallmark of relative superiority and was included as inlay and veneers in the twilight of medieval pattern welding.

What I really wanted to emphasize in the above post, is that, to me, it is more amazing that these dark age swordsmiths could forge such fine and thin layers of steel into the edge of the blades for the full length of a 30 inch blade than that they could forge weld a bundle of twisted billets together in the core. Also I wanted to suggests that even if we were to accept the most extreme view that pattern welding was only decorative then, in terms of superiority, we still must deal with the issue of these welded on edges and especially the layered sandwich type edges with high carbon steel cores. Who is going to say that this is only decorative? It is clear to me that this was obviously meant to be functional and the experts seem to agree on this point. So... If we were to ask if there was a natural superiority in function with these pattern welded prestige weapons the answer would be yes, even if the patterns were only "bling bling." :D

| Jeroen Zuiderwijk wrote: |

|

...Well, the general idea I get is that the smiths tried to create a harder edge, and a tougher core. The latter can be done in various ways, one of which is by creating nice looking torsion damast. While the patterns may be decorative, and the same effect could have been achieved by other methods, that doesn't mean the patternwelding was only decorative. |

Great point... And to add to it (and probably open another can of worms): The very fact that they are experimenting with so many "various ways" and patterns in the core would suggest that they are trying to increase some functional aspect. If someone countered that the variety was simply the ever increasing desire for the "new" in decoration then, in IMHO, they don't understand the ancient mind. The obsessive "quest for the new" is a modern condition. The ancients were much more conservative. They believed, and I say this in very general terms, that old was good (tested and proven) and new was bad (unproven and chancy)... just the opposite of the modern tendency. That would explain why decorative trends, as well as technological status quo existed for centuries or longer. For instance with pattern-welding designs, it may look as if they had tried every pattern that could be imagined. However there seems to be some patterns that have not been found as of yet but would have a really nice look. As a matter of fact it was on of these patterns I really liked when designing the reconstruction of the Fetter Lane sword. It involves billets side-by-side twisted in the same direction and offset on each side of the core. I will try to post an image.

It gives a very nice decorative effect but was so unperiod that Barta reversed the outer billets to be more in keeping with period patterns.

take care

ks

| Jeroen Zuiderwijk wrote: | ||

|

I will phrase the claim differently. I have not researched it carefully and am very interested in actual known "steel" production within Central Europe prior to the blast furnace. Bloomery steel can be produced, but when it really began is a great subject for post by itself.

Central Europe had a very solid medieval industry and internal trade in "iron." Production of raw commodities of steel suited for spring temper swords with approximately 1% carbon or higher is hard to prove in central Europe prior to some time near the 13th century (starting into the blast furnace and bloomery steel era.)

Much earlier, several neighboring regions are accepted as steel producers. Some of this may be a result of the raw mineral composition of their available ores. Repeatedly, these production techniques appear to be crucible based. Below are some non India based production examples, still not what I consider to be central Europe.

Kurdish? Crucible steel production also known in Merv Turkmenistan during the 9th century

http://www.scienceblog.com/community/older/1999/B/199901581.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merv

Israel

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0006-0895(19...0.CO%3B2-9

Egypt was a producer but I can not recall the link or article.

This article actually characterizes metalurgical technology and refinement capabilities within central Europe as experiencing a downturn during the "dark ages."

http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/jom/0508/ehrenreich-0508.html

Primary areas accepted as having early production capabilities were; Yunan China, India/ Sri Lanka, and primarily trade but some production in central Eurasia. The "vikings" or norman saxons traded extensively with these areas for many centuries through Russia. The name of the country of Russia is actually derived from Scandinavian "Rus", with Scandanavian settlement evidence there predating the 9th century. They left some of their own objects behind in Russia as well. There are a couple of great ancient trade maps that illustrate pretty much global trade from the Eastern countries (accepted steel producers) through central Europe and into England throughout much of the dark ages. The Norman-vikings have the credit for this. An they do appear to be the first to produce semi-modern quality steel swords within central Europe.

http://www.viking.no/e/info-sheets/russia/e_kremlin_treasure.htm

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/9529/scanrus.htm

| Jeff Pringle wrote: |

| A more recent look at alloy and hardness of some Merovingian Swords, spears & etc.

http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/jom/0508/Ehrenreich-0508.html |

Thanks for posting that fascinating article Jeff.

The conclusion seems to contradict the previously held theory (stated recently in this thread) that the quality of metalurgy diminished during the 'Dark Age' period, from what they said neither the Romans nor otherr Iron Age weapons were any better, a wide range of quality seems to have existed from the Iron Ages through the medieval.

It's also interesting how the non heat-treated weapons, spearheads, arrowehads etc. were made with high-phosphorous iron.

Very interesting read that, thanks again.

J

One can read that article with several interpretations. Only one sword showed signs of optimal quench hardening.

In general terms, understanding of the metalurgy and tempering process did not really become established until 10th century.

Pattern welding of swords supposedly peaked around 11th to 12th century, with mass production of superior (more homegenous steel) becomming very well known in very early 14th century in central Europe.

In general terms, understanding of the metalurgy and tempering process did not really become established until 10th century.

Pattern welding of swords supposedly peaked around 11th to 12th century, with mass production of superior (more homegenous steel) becomming very well known in very early 14th century in central Europe.

| Quote: |

| In general terms, understanding of the metalurgy and tempering process did not really become established until 10th century. |

Really, an understanding of the metallurgy of steel did not happen until the 19th C., but quenching and tempering were grasped in an empirical way very early, certainly long before the tenth century. The martensitic ‘sword’ from the JOM article can be seen on the museum’s website:

http://www.spurlock.uiuc.edu/search/details.php?a=1924.02.0309

The museum is being cagey on date and location, but even with the tiny photo they provide you can say the blade shape is consistent with the standard large Frankish seax, common from the 6th to 8th centuries. I’m sure better provenanced examples of hardened and tempered blades can be found if you feel like looking. Some (most?) swords were not hardened because the smiths didn’t think swords should be hardened, not because they didn’t understand quenching (in my opinion, of course ;) ). Why this is so could be fun to speculate on, but a normalized blade is probably tough and fatigue resistant, and still deadly. More interesting speculation could be had on why some swords were hardened and some not, but we need a lot more info for that to be profitable.

| Quote: |

| Pattern welding of swords supposedly peaked around 11th to 12th century, with mass production of superior (more homegenous steel) becomming very well known in very early 14th century in central Europe. |

European PW swords disappear for the most part in the tenth century, immediately replaced by plain steel – Ulfberht (9th) & Ingelrii (10th) are not structurally PW, and for me symbolize the demise of PW as sword technology in early Europe. Leaf through “Swords of the Viking Age” and you’ll see the story through the rust. By the swords of the crusades, 12th century, it’s all over – no Damascus was going to Damascus on the way to Jerusalem.

Thanks Jeff!

I had been looking casually for some time regarding evidence of steel and heat treatment in an early period central European sword. It is fantastic to have something concrete to reference. I can't read many specifics in the link, and would appreciate it if you could tell the forum a little about it (estimated age, region it came from, anything else cool.)

Seperately, if you know of any evidence of early bloomery steel production in dark ages central Europe, please share it. It is hard to find through simple internet searches, if it has been written about at all.

My "theory" on why Saxons pattern welded could be totally bunk. I still desire a rational or understanding of why saxons would have utllized a particularly difficult technique (such as pattern welding) for several centuries. It becomes even more mysterious if they did not do heat treat after going through all of that work.

Some researchers have done analysis on surviving wootz and pattern welded swords and concluded that the results were not as good as modern steel (inconsistent carbon content and structure, more prone to ductile bending failure, etc.) but still exceptionally good for pre-modern steel.

I am wondering if the basic process of diffusion during welding would have accidentally imparted semi-effective spring temper (many examples are low hardness such as 30 to 35 Rockwell C) , or if many swords were tempered but have never been assessed archeologically to prove the issue. Modern pattern welders specify a fairly simple heat treat process (often something like heat whole blade to 1400 for 15 minutes, quench in 150 F bath of oil or brine for 30 seconds.) This seems well within reach of a dark age Smithy's capabilities.

I had been looking casually for some time regarding evidence of steel and heat treatment in an early period central European sword. It is fantastic to have something concrete to reference. I can't read many specifics in the link, and would appreciate it if you could tell the forum a little about it (estimated age, region it came from, anything else cool.)

Seperately, if you know of any evidence of early bloomery steel production in dark ages central Europe, please share it. It is hard to find through simple internet searches, if it has been written about at all.

My "theory" on why Saxons pattern welded could be totally bunk. I still desire a rational or understanding of why saxons would have utllized a particularly difficult technique (such as pattern welding) for several centuries. It becomes even more mysterious if they did not do heat treat after going through all of that work.

Some researchers have done analysis on surviving wootz and pattern welded swords and concluded that the results were not as good as modern steel (inconsistent carbon content and structure, more prone to ductile bending failure, etc.) but still exceptionally good for pre-modern steel.

I am wondering if the basic process of diffusion during welding would have accidentally imparted semi-effective spring temper (many examples are low hardness such as 30 to 35 Rockwell C) , or if many swords were tempered but have never been assessed archeologically to prove the issue. Modern pattern welders specify a fairly simple heat treat process (often something like heat whole blade to 1400 for 15 minutes, quench in 150 F bath of oil or brine for 30 seconds.) This seems well within reach of a dark age Smithy's capabilities.

There is another enigma of Saxon pattern welding. FLUX.

Forging higher carbon steels and iron together requires a specialized flux (chemical that prevents oxidation from ruining the welds but still permits fusion.) Modern artisan pattern welders use mixtures that are composed predominantly of Borax (sodium borates.) As far as I know, there are no “naturally occurring” alternatives to Borax that are adequate for the pattern welding technique. Alternate chemicals exist, but are products of advanced chemical synthesis. There are only two known regions where naturally occurring mineral deposits of Borax occurs; Turkey and the U.S. Mohave desert town named Borax. Today, some Borax sold for welding is chemically synthesized, but something like 60% of it is still mined, primarily in Turkey.

The Turkish deposits were known and utilized for glazing in ancient China and even found in mummification in ancient Egypt. The actual name for it is based upon Persian “buraq”. It was utilized throughout the middle-East regions also known for production of fine Damascus - wootz swords, which also are accepted as known centers of crucible production of the highest carbon steels available during the “Dark Ages.”

So here is the enigma… If the Saxons produced their pattern welded swords entirely from local mineral resources what were they using for flux? Where did they get it? Did they also have advanced chemical capabilities in addition to high carbon steel production not yet discovered by archeologists?

They could have acquired all of the non-native materials and the processing technology required for pattern welding and heat treatment on a single trade stop during the 9th century either in the mid-East or far-East. This is about the time pattern welding really becomes significant for “Vikings.”

Forging higher carbon steels and iron together requires a specialized flux (chemical that prevents oxidation from ruining the welds but still permits fusion.) Modern artisan pattern welders use mixtures that are composed predominantly of Borax (sodium borates.) As far as I know, there are no “naturally occurring” alternatives to Borax that are adequate for the pattern welding technique. Alternate chemicals exist, but are products of advanced chemical synthesis. There are only two known regions where naturally occurring mineral deposits of Borax occurs; Turkey and the U.S. Mohave desert town named Borax. Today, some Borax sold for welding is chemically synthesized, but something like 60% of it is still mined, primarily in Turkey.

The Turkish deposits were known and utilized for glazing in ancient China and even found in mummification in ancient Egypt. The actual name for it is based upon Persian “buraq”. It was utilized throughout the middle-East regions also known for production of fine Damascus - wootz swords, which also are accepted as known centers of crucible production of the highest carbon steels available during the “Dark Ages.”

So here is the enigma… If the Saxons produced their pattern welded swords entirely from local mineral resources what were they using for flux? Where did they get it? Did they also have advanced chemical capabilities in addition to high carbon steel production not yet discovered by archeologists?

They could have acquired all of the non-native materials and the processing technology required for pattern welding and heat treatment on a single trade stop during the 9th century either in the mid-East or far-East. This is about the time pattern welding really becomes significant for “Vikings.”

| Jared Smith wrote: |

| So here is the enigma… If the Saxons produced their pattern welded swords entirely from local mineral resources what were they using for flux? |

| Quote: |

| I had been looking casually for some time regarding evidence of steel and heat treatment in an early period central European sword. It is fantastic to have something concrete to reference. I can't read many specifics in the link, and would appreciate it if you could tell the forum a little about it (estimated age, region it came from, anything else cool.) |

I think you’ll need to google in German or French, most of the info is probably not in English. There are no specifics in the link, the museum is probably being careful since it came from a private collection and they don’t have further provenance (i.e. find location and ownership trail). I’m just sayin the blade looks a lot like one of these:

[ Linked Image ]

this one from the Netherlands and ~8th Century, but they crop up in Frankish cemeteries, sometimes with rivet holes in the tangs.

| Quote: |

| Forging higher carbon steels and iron together requires a specialized flux (chemical that prevents oxidation from ruining the welds but still permits fusion.) Modern artisan pattern welders use mixtures that are composed predominantly of Borax (sodium borates.) |

Modern guys are working for the most part with modern steels, which don’t act at all like pre-industrial metal. Once you’ve built a smelter and made some steel the old fashioned way, you’ll find it welds like a dream. And yes, plain silica sand is a common flux for forge welding iron and steel, borax is unnecessary. However, Theophilus, that German monk who wrote about smithing in 1120 AD, mentions borax IIRC, so it’s not like it was unavailable in the dark ages. See “On Divers Arts” for period descriptions of things like quenching (he describes hardening files and engraving tools), but make sure you have the goat & the ferns to feed it before you try it at home! :D

All this information is helpful, but I think relation to my original question about sword production in regions outside Roman influence we need to look at the swords in Britain before the Roman conquest compared to those on the continent. I find it hard to belief that quality deteriorated in the far North of Britain, perhaps in Ireland as there was a sea seperating the two islands. What do you think?

About the sand...

Nobody claims to be certain how ancient pattern welding was done, but several modern pattern welders recycle excess flux by letting it run off into a bucket of sand. They later reclaim it and reuse it. Today they are picky about sifting and separating the sand out though. As far as I know, sand will not act as a flux itself. Smooth grinding and close surface contact between the metal layers prior to forge welding is actually critical. The sand is a "bad thing" in terms of the quality of the composite blade's strength and integrity of the welds.

I honestly can not say I have heard of anyone attempting sand as a flux, although people have been intensly experiementing with reinventing how to do it for almost half a century now, and insist that the flux is critical and needs to be more than 90% Borax. Fluxes containing significant carbon powder will actually bond iron to spring grade steel, but these types of fluxes nearly destroy the cosmetic quality of the pattern welding and are not representative of the few surviving blades that have been assessed metalurgically.

Sand could possibly stop oxidation and diffusion loss of the carbon, and might also have been used as a protective layer during heating, or to protect sections of a heated blade not being prepared for the immediate section of forging. Sand is also a constituent impurity of crucible steel, which I am "theorizing" would have been the source of appropriate carbon content steel in these pre-modern blades that resemble steel. Sand inclusion was generally not a problem in pure iron production.

If someone does have a naturally occurring working alternative to Borax flux that still produces the beautiful patterns of classic pattern welded blades with dependable forge welding characteristics, it woulud be considered a major discovery by dozens of major artisans who have devoted their life careers to experiementing with and advancing the art of pattern welding.

Nobody claims to be certain how ancient pattern welding was done, but several modern pattern welders recycle excess flux by letting it run off into a bucket of sand. They later reclaim it and reuse it. Today they are picky about sifting and separating the sand out though. As far as I know, sand will not act as a flux itself. Smooth grinding and close surface contact between the metal layers prior to forge welding is actually critical. The sand is a "bad thing" in terms of the quality of the composite blade's strength and integrity of the welds.

I honestly can not say I have heard of anyone attempting sand as a flux, although people have been intensly experiementing with reinventing how to do it for almost half a century now, and insist that the flux is critical and needs to be more than 90% Borax. Fluxes containing significant carbon powder will actually bond iron to spring grade steel, but these types of fluxes nearly destroy the cosmetic quality of the pattern welding and are not representative of the few surviving blades that have been assessed metalurgically.

Sand could possibly stop oxidation and diffusion loss of the carbon, and might also have been used as a protective layer during heating, or to protect sections of a heated blade not being prepared for the immediate section of forging. Sand is also a constituent impurity of crucible steel, which I am "theorizing" would have been the source of appropriate carbon content steel in these pre-modern blades that resemble steel. Sand inclusion was generally not a problem in pure iron production.

If someone does have a naturally occurring working alternative to Borax flux that still produces the beautiful patterns of classic pattern welded blades with dependable forge welding characteristics, it woulud be considered a major discovery by dozens of major artisans who have devoted their life careers to experiementing with and advancing the art of pattern welding.

Jeff,

If I only speak English, is there a workable technique for Googeling in another language? At present I am using Firefox which may disable some functions. It seems to be good at stopping "pop ups" though......

If I only speak English, is there a workable technique for Googeling in another language? At present I am using Firefox which may disable some functions. It seems to be good at stopping "pop ups" though......

| Jared Smith wrote: |

| At present I am using Firefox which may disable some functions. It seems to be good at stopping "pop ups" though...... |

Firefox does not diminish Google's functionality. I do, however, suggest going to Google's site and using their actual page rather than any in-browser search bars. This is the only way you have access to the entire Google suite of tools.

| Jared Smith wrote: |

| About the sand...

.... I honestly can not say I have heard of anyone attempting sand as a flux, although people have been intensly experiementing with reinventing how to do it for almost half a century now, and insist that the flux is critical and needs to be more than 90% Borax. Fluxes containing significant carbon powder will actually bond iron to spring grade steel, but these types of fluxes nearly destroy the cosmetic quality of the pattern welding and are not representative of the few surviving blades that have been assessed metalurgically. ... |

Jared, I have welded with fine quarts sand, that a friend and fellow smith (Per Alnaeus) personally had collected from a natural deposit. It is as fine as the sand you would use for a small egg timer: almost dust like.

I know several other smiths who at times use quartz sand for welding.

It is a little different , but works pretty well.

I will use it when welding simple carbon steels.

I do not do a lot of patternwelding, but I have tried this in a couple of instances.

Unfortunately I have not yet had the opportunity to work with home smelted steel, but I expect that would work even better.

As to the original question about swords in the british isles in ancient times, I cannot add much.

There is some similarity to early iron age in scandinavia, however.

Spears and axes were reguarly made in local centres of production. They follow common types but show clear signs of goegraphical variation in style.

As swords go, those of sword type that were used in the centuries BC, were regularly of single edged type up till roman times. These single edged swords has been discussed in various topics on this forum before. They can have ofset tangs like great big kitchen knives, or have central whittle tangs that were mounted in solid wood or bone grips. Some has simple bronze ferrules, bur mounting was normally quite plain. There is also a type that seems to be a cross between a straight razor and a bayonette with a strong T-shaped cross section.

There are also finds of double edged sword imported from Celtic areas: weapon of La Tène type.

The straight double edged sword does not seem to be part of the repetoir of the scandinavian weapon smiths in the early iron age.

We have one or two very rare finds of iron Hallstatt swords (most certainly imported), but then there is a lag in find of iron bladed swords/knives of a few hundred years. This is a bit of a mystery.

When we do find bladed weapons of sword type again, they look like long murderous steak knives. They are well represented in the Danish Hjortspring find dating to 350 BC.

The Hjortsping find included traces of several mail shirts, a multitude of spears and shileds and a small number of war knives or single edged swords. The proportion between the different weapon types has led to the theory that only the officers or leaders were equipped with swords, about one warrior in ten.

When the roman empire gained influence on the continent it had effect also on far away scandinavia. We start to find weapons of gladius type and later on also spathae. These blades are thought to be imported with very few exceptions. There are clear roman makers marks in many of the blades.

Sometimes the hilts are of roman manufacture, sometimes they are hilted in local fashion (still very roman looking, but with a bit of the barbarian taste).

The locally made single edged swords survived for a time alongside the imported roman blades, especially in isolated areas. By the second century AD few single edged swords were being produced. Instead the seax became the short side arm for those who could afford a long and a short blade or for those who had to make do with only the short. The lance and seax is a common combination of weapons in iron age graves in scandinavia during the roman period. Swords were not completly unique, as many have been found (especially in bog deposits), but they seem to have been used by warriors of influence and status.

This situation gadually changes as we reach the period we call the Viking age, when swords were more numerous and well distributed.

I would suspect you could find a similar roman influence in the british isles. Perhaps the war knife fulfilled the role of the sword after the demise of the double edged bronze sword?

| Quote: |

| we need to look at the swords in Britain before the Roman conquest compared to those on the continent. |

The aforementioned “British Iron Age Swords and Scabbards” has a metallographic appendix, with some speculation as to methods & evolution of technology, but I haven’t had a chance to read it yet. It might make a good comparison to the Merovingian analysis in the JOM or Tylecote.

| Quote: |

|

If I only speak English, is there a workable technique for Googeling in another language? |

I guess I’ve used two techniques in the past: First, back-tracking bibliographies in books, the non-English titles and authors can lead you to other pages referencing those book or other books by the author or on the subject of interest, you can work your way back to original archaeological papers pretty quickly, and the search will generally stay on-topic.

Secondly, coming up with the search terms in other languages is not as hard as learning the whole language, so for example, ‘sword’ (Amurrican), ‘sverð’ (Icelandic), ‘sverd’ (Norwegian), ‘schwert’ (German) and ‘zwaard’ (Netherlandish) will all give different results (of course, just searching ‘sword’ by itself will result in a lot of crap to wade though, so adding another translated term is advised ;) ).

I’ve mainly used this for finding original records of various artifacts, so I’m mostly looking at the pictures. Once you have the document in front of you, though, it’s pretty easy to figure out which text is of interest, and roughly what it is saying.

I did once spend about 40 bucks on a journal only to find out when it arrived from the rare book dealer that the article was about carpenter’s axes, so the method is not without pitfalls.

:surprised:

Thanks Jeff and Peter. I think you have convinced me.

This link illustrates the method Peter described with quartz sand as flux. I was able to find it after searching for quartz as a welding flux. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ho/06/eue/hod_55.46.1.htm

This museum link describes a sword as made from "alternating rods of steel and iron." http://users.utu.fi/mikmoi/construction.htm

I suspect the museum description is misleading and that the rods would be better characterized as varying grades of iron. So far, I have not found evidence of steel in NorthWest European regions other than "bog" or low carbon wrought iron and mild carbon (0.7% or less) however it was produced. Some crucible steel was traded out of Syria to the Genoese in Italy, but evidence is not conclusive before the 12th century.

It is supposedly very difficult to weld plain low carbon steels or iron to higher carbon "alloy steel". Particularly so as you begin to introduce nickle, vanadium, chromium, and elements of stainless steels into the alternating layers to really make the contrast distinct. This is where specialized flux becomes necessary, and what modern pattern welders are doing to make the layers show up with beautiful contrast. I suspect that this is closer to what we see in some of the fantastic examples by Barta, who appears to have a sort of a blast furnace or bloomery forge for production of iron and steel. What seems to be characterized in the metallurgy of the Dark Ages non Eastern blades is "mildly carburized iron", ranging from 0.3% to 0.7% in better cases. This is still not alloy steel, but is impressive if carbon is being achieved through piling and simple hearth forge facilities. If all rods were actually low grade iron, they might be welded with a good forge using no flux at all. This would still have a beautiful look where the slag lines would reveal the look of the twisting and lamination of layers performed as part of the forging. I doubt you could get a spring temper from it though.

This link illustrates the method Peter described with quartz sand as flux. I was able to find it after searching for quartz as a welding flux. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ho/06/eue/hod_55.46.1.htm

This museum link describes a sword as made from "alternating rods of steel and iron." http://users.utu.fi/mikmoi/construction.htm

I suspect the museum description is misleading and that the rods would be better characterized as varying grades of iron. So far, I have not found evidence of steel in NorthWest European regions other than "bog" or low carbon wrought iron and mild carbon (0.7% or less) however it was produced. Some crucible steel was traded out of Syria to the Genoese in Italy, but evidence is not conclusive before the 12th century.

It is supposedly very difficult to weld plain low carbon steels or iron to higher carbon "alloy steel". Particularly so as you begin to introduce nickle, vanadium, chromium, and elements of stainless steels into the alternating layers to really make the contrast distinct. This is where specialized flux becomes necessary, and what modern pattern welders are doing to make the layers show up with beautiful contrast. I suspect that this is closer to what we see in some of the fantastic examples by Barta, who appears to have a sort of a blast furnace or bloomery forge for production of iron and steel. What seems to be characterized in the metallurgy of the Dark Ages non Eastern blades is "mildly carburized iron", ranging from 0.3% to 0.7% in better cases. This is still not alloy steel, but is impressive if carbon is being achieved through piling and simple hearth forge facilities. If all rods were actually low grade iron, they might be welded with a good forge using no flux at all. This would still have a beautiful look where the slag lines would reveal the look of the twisting and lamination of layers performed as part of the forging. I doubt you could get a spring temper from it though.

I got the above links backwards. They are the correct ones though...

Page 2 of 3

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum