Hello. I know you probably get this a lot but I can't seem to find much info on the internet about it. I wondered just how advanced the sword making techniques were of the groups that inhabited the British Isles during the Dark Ages. I understand that the Romans perhaps brought some continuity in manufacture to the inhabitants of Britain but I'm also aware that before the Roman Conquest sword manufacture has apparently been found to be inferior to that practiced by the Celts on the continent and so I'm quite interested in knowing about the techniques of groups such as the Picts and Scotti who remained relatively untouched if anyones has information. As this was the time of high point of pattern welded swords and the introduction of better steel (from the likes of Catalonia) how did swords compare with those on the continent?

I'm no expert on this subject but I believe that the Picts and Scotts used mainly spears and such. I don't believe swords were a very common thing with the tribes on the island until the Vikings, Angles, and Saxons inhabited it. As I said, I'm no expert so if I am wrong, please somone correct me.

I know the above doesn't answer your question, I'm trying to show that the sword wasn't very popular, so it would be reasonable to assume that the quality would not be as high as that of the continental swords. This is just my interpretation, and of course if my facts are wrong then my interpretation is totally wrong so don't take all of this as set in stone. Clarification (or correction) from someone with a little more knowledge in this area would be nice.

I'm not sure if I just created more confusion but I hope I was of at least some help to someone...

-James

I know the above doesn't answer your question, I'm trying to show that the sword wasn't very popular, so it would be reasonable to assume that the quality would not be as high as that of the continental swords. This is just my interpretation, and of course if my facts are wrong then my interpretation is totally wrong so don't take all of this as set in stone. Clarification (or correction) from someone with a little more knowledge in this area would be nice.

I'm not sure if I just created more confusion but I hope I was of at least some help to someone...

-James

| J. Bedell wrote: |

| I'm no expert on this subject but I believe that the Picts and Scotts used mainly spears and such. I don't believe swords were a very common thing with the tribes on the island until the Vikings, Angles, and Saxons inhabited it. As I said, I'm no expert so if I am wrong, please somone correct me. |

I´m no expert either but I would guess that swords where around long befor the Angles and Saxons came to the islands. For starters there where trade going on with the Gaulish cusins on the continent long before the Roman invasions. And the Gaulish tribes had swords, good ones. Then we have more than 400 years under the Roman sword. This must have left a good quantity and quallity of gladii and spathae on the Brittish. Just of top of my mind early a thursday morning after a long night of poker.

Iron age and early medieval britain are not my main focus. At least in the bronze age, Scotland had pretty good bronze swords. I don't know if any iron age swords can be associated directly with the Picts or the Scots, but speaking generally of the UK, there are quite a lot of pretty good swords found from the iron age. I haven't seen much in terms of metalurgical reports though. During the dark ages, there's not much difference between continental and British swords that I'm aware of, at least in typology (there's a difference in seax design, but the spathae don't seem to be very different). Ireland is different though. It appears that only small, gladius-like swords were used during the early medieval period. Also from the iron age, there aren't that many iron swords that I'm aware of, and they all appear to be quite short and of soft iron.

The brits had good swords before the Romans, "British Iron Age Swords and Scabbards" by I.M. Stead, published by the British Museum last year, goes into great detail on the La Tene period swords of the British Isles, from the fourth century BC up to the Romans. Really great book! Lots of technological details.

After the Romans, sword quality was congruent with the continent. The introduction of better steel is what killed pattern welding, but that didn't happen until about the tenth century. Although improved smelting probably developed on the continent, there wasn't an appreciable lag before the new technology was adopted in Britain.

(Or so it seems to me, but after the pattern welding drops out, so does my interest, so someone else will have to pick up the ball in the eleventh century)

:D

After the Romans, sword quality was congruent with the continent. The introduction of better steel is what killed pattern welding, but that didn't happen until about the tenth century. Although improved smelting probably developed on the continent, there wasn't an appreciable lag before the new technology was adopted in Britain.

(Or so it seems to me, but after the pattern welding drops out, so does my interest, so someone else will have to pick up the ball in the eleventh century)

:D

| Jeff Pringle wrote: |

| The brits had good swords before the Romans, "British Iron Age Swords and Scabbards" by I.M. Stead, published by the British Museum last year, goes into great detail on the La Tene period swords of the British Isles, from the fourth century BC up to the Romans. Really great book! Lots of technological details.

After the Romans, sword quality was congruent with the continent. The introduction of better steel is what killed pattern welding, but that didn't happen until about the tenth century. Although improved smelting probably developed on the continent, there wasn't an appreciable lag before the new technology was adopted in Britain. (Or so it seems to me, but after the pattern welding drops out, so does my interest, so someone else will have to pick up the ball in the eleventh century) :D |

On the subject of pattern welding, were pretty much all swords made before the mini industrial revolution around the first milennia pattern welded? I know that iron was mainly coming from bog-iron and tended to be smelted in small quantities of varying carbon content which is a major reason pattern welding was used as a technique, but what percentage of swords were pattern welded versus say, essentially homogenious? Also within the subset of pattern welded swords how many were simply hard edges welded to softer cores vs (arguably) more sophisticated matrixes?

How about Roman swords? I understand they did some pattern welding but most of the (few) surviving Roman swords I've seen from Fulham, Mainz, Pompeii and other sites look like they are made of more homogeneous steel ('steely iron'?), of course that could just mean they were not etched to show the pattern... did the Romans have different smelting techniques than the 'Barbarians'? Did they have some kind of large scale manufacturing processes utilizing slave labor or something? They certainly would have had to have made a LOT of swords and daggers, and armor, to equip all of those Legions...

I realise any response to this would be essentially speculative but I'm just wondeirng from those of you who have some sense of the range of Iron Age weapons recovered from Europe, how often one type seems to show up compared to another.

Jean

There is a chapter in Mike Bishop's & J.C. Coulston's Roman Military Equipment from the Punic Wars to the Fall of the Empire that discusses manufacturing techniques under the Romans. Among other things, they have analyzed a number of sword blades and many of them appear to have been homogeneous, some of iron with a steel edge welded in but some of all steel.

A n International History Channel special was broadcast last night (Wednesday January 3rd, 2007) regarding a warrior skeleton excavated at a military base in Suffolk England. The man was carbon dated as 1400 years old (placing him about 600 A.D. which some would consider Dark Age era.)

I will summarize what was described.

The warrior was determined to be 5' 10" tall with strong build and good nutrition and health based on the skeletal remains. No wounds or accidental causes of death were evident. The warrior was positioned prostrate with a hand over a sword that rested upon the length of his leg. The sword was badly corroded but the archeologists were able to cast a plastic over it and keep it intact and determine an amazing amount of things about its structure through off site examination. I was a double edged cruciform with a large and straight cross guard - (closer to an Oakeshotte type X or XI than any Viking category.) The pommel was a pyrimidal form similar to the pommel of a viking style, whereas the rest of the sword and guard would easily be mistaken for a 11th to 13th century weapon. X ray examination of the blade revealed a classic patternwelded construction, judged to be a stacked pile type with different steel at the center of the edges, classic opposed twist rod style core. There was also a rotted but intact spear and spear head that would have been very passable for a 10th or 11th century Norman cavalry spear, except possibly a little short on the order of 9 to 10 feet long.

He was buried with his horse which was 14 hands tall. The horse's bridle and several fittings were restored and revealed to be very decorately and finely worked bronze pieces, many of which were ornamental chapes at the end of excess straps. There was deterioration in one of the hock joints of a rear leg of the horse which suggested a severe bruise had occurred and the horse probably had arthritis and some degree of permanent lameness.

Also, some youth were found buried near by, all of which had a spear smilar to the adult warrior's spear placed within their graves.

I will summarize what was described.

The warrior was determined to be 5' 10" tall with strong build and good nutrition and health based on the skeletal remains. No wounds or accidental causes of death were evident. The warrior was positioned prostrate with a hand over a sword that rested upon the length of his leg. The sword was badly corroded but the archeologists were able to cast a plastic over it and keep it intact and determine an amazing amount of things about its structure through off site examination. I was a double edged cruciform with a large and straight cross guard - (closer to an Oakeshotte type X or XI than any Viking category.) The pommel was a pyrimidal form similar to the pommel of a viking style, whereas the rest of the sword and guard would easily be mistaken for a 11th to 13th century weapon. X ray examination of the blade revealed a classic patternwelded construction, judged to be a stacked pile type with different steel at the center of the edges, classic opposed twist rod style core. There was also a rotted but intact spear and spear head that would have been very passable for a 10th or 11th century Norman cavalry spear, except possibly a little short on the order of 9 to 10 feet long.

He was buried with his horse which was 14 hands tall. The horse's bridle and several fittings were restored and revealed to be very decorately and finely worked bronze pieces, many of which were ornamental chapes at the end of excess straps. There was deterioration in one of the hock joints of a rear leg of the horse which suggested a severe bruise had occurred and the horse probably had arthritis and some degree of permanent lameness.

Also, some youth were found buried near by, all of which had a spear smilar to the adult warrior's spear placed within their graves.

The name of the program was "Meet the Ancestors, Warrior." It should repeat on Wednesdays this month.

| Quote: |

| On the subject of pattern welding, were pretty much all swords made before the mini industrial revolution around the first milennia pattern welded? |

Since the main way to refine bloomery metal is by folding and re-welding, you could call everything pattern welded (PW), but it seems like most books refer to the straight grained stuff as ‘piled construction’ and save PW for where the smith is manipulating the material for decorative effect. I think this first starts showing up in late Roman times, see for example artifacts from Nydam Bog. I would guess that PW has never accounted for a majority of weapons made in any particular era, but since more prestige weapons would be PW a straight survey of artifact numbers might make them seem more plentiful than they were.

I bet the Romans had a more industrial approach to smelting than the ‘barbarians,’ but I don’t know if they had different furnaces or ways of treating the ore.

| Jeff Pringle wrote: | ||

Since the main way to refine bloomery metal is by folding and re-welding, you could call everything pattern welded (PW), but it seems like most books refer to the straight grained stuff as ‘piled construction’ and save PW for where the smith is manipulating the material for decorative effect. I think this first starts showing up in late Roman times, see for example artifacts from Nydam Bog. I would guess that PW has never accounted for a majority of weapons made in any particular era, but since more prestige weapons would be PW a straight survey of artifact numbers might make them seem more plentiful than they were. I bet the Romans had a more industrial approach to smelting than the ‘barbarians,’ but I don’t know if they had different furnaces or ways of treating the ore. |

Ok and this leads me to my other question.

I know this will be contraversial so bear with me.

I believe I understand the consensus about pattern welding is that it's only effect was as decoration. I have many times read the argument that pattern welded steel and even wootz steel are no 'better' in any way than modern, or even medieval homogeneous steel.

My question is do we know this for sure?

I know that a lot of people learn about wootz ('damascus') steel or pattern welding and immediately latch on to it as some sort of "magic" weapon ala Tolkein or Dungeons and Dragons. Please bear with me I'm not one of those people.

But I do wonder if there were any properties with the ancient pattern welded blades, or the wootz steel blades which made them more effective as weapons.

I know for example there has recently been a big contraversy about the so called carbon "nano-tubes" and cementite "nano wires". I gather this has largely been dismissed in the spathology community. Certainly we don't have enough comparative evidence of the structure of homogeneous and wootz steel swords to make any real conclusions yet but it 's definately interesting.

On the face of it, the much higher carbon content in wootz would seem to allow the metal to be harder and therefore sharper than many other contemporary steels, if not modern varieties. The fact that it retains flexibility (if I understand this correctly) makes it have a combination of the two ideal features of a sword: hardness and springiness.

I'm just a layman and have never made a sword, but the combination of hard and softer steels in a pattern welded blade, could concievably if it were constructed the right way, contribute to a combination of greater flexibility and greater hardness.

There was a Scientific American article about ten years ago describing the interesting role trace amounts of Vanadium played in the microscopic structure of wootz steel.

http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/JOM/9809/Verhoeven-9809.html

I've read somwhat similar analysis of the role of trace elements such as phosphorus in some Viking swords.

My question is, does everyone think pattern welded and wootz (either or) are simply decorative effects or are there some enhcancement of physical properties over homogenous steels? Do we really have evidence to know either way yet?

Jean

Last edited by Jean Henri Chandler on Fri 05 Jan, 2007 10:17 am; edited 1 time in total

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: |

| My question is, does everyone think pattern welded and wootz (either or) are simply decorative effects or are there some enhcancement of physical properties over homogenous steels? Do we really have evidence to know either way yet?

Jean |

Jean,

I'm not the best person to answer this, but as far as we know, a pattern-welded piece made today won't have any significant advantage over a monosteel piece made today. But, the situation was very different "back in the day." A smith would not necessarily have had enough high quality steely iron with which to make a monosteel sword. If he did, he might not have wanted to use it all up on one sword, nor might a customer be able to pay for it if he did.

My understanding is that pattern welding in Europe emerged to solve the challenge of not having enough good steel/steely iron to make a whole blade. So the smith would take the good stuff and combine it with other stuff. He might save the good hardening steel for the edges, while taking some other pieces of iron and forging them together to make the center of the blade. This could yield a blade with desirable qualities, since the good steel could hold an edge while the central core of iron would be softer and more flexible.

I think it had much to do with the widespread availability of the raw materials (or lack thereof). If people had had better access to a higher quality steel, we might not have seen pattern welding develop as it did.

If dated to 600 AD and found in Suffolk the man was most likely Anglo-Saxon. Does anybody know anything about the swords the Roman-British used? I presume they would have followed the Roman style for a while but obviously I can't say for sure. Before the Roman conquest I read that more advanced techniques were introduced around 150 BC by the Belgae tribes. It suggested that the techniques had been in use on the continent for a while and I find it hard to understand how the technology could not have been passed sooner considering their is only a small body of water between Gaul and Britain.

| Russel Foxtrot wrote: |

| If dated to 600 AD and found in Suffolk the man was most likely Anglo-Saxon. Does anybody know anything about the swords the Roman-British used? I presume they would have followed the Roman style for a while but obviously I can't say for sure. Before the Roman conquest I read that more advanced techniques were introduced around 150 BC by the Belgae tribes. It suggested that the techniques had been in use on the continent for a while and I find it hard to understand how the technology could not have been passed sooner considering their is only a small body of water between Gaul and Britain. |

At 150 BC I would guess you might be talking about the introduction of Iron...?

Jean

| Quote: |

| Jean,

My understanding is that pattern welding in Europe emerged to solve the challenge of not having enough good steel/steely iron to make a whole blade. So the smith would take the good stuff and combine it with other stuff. He might save the good hardening steel for the edges, while taking some other pieces of iron and forging them together to make the center of the blade. This could yield a blade with desirable qualities, since the good steel could hold an edge while the central core of iron would be softer and more flexible. I think it had much to do with the widespread availability of the raw materials (or lack thereof). If people had had better access to a higher quality steel, we might not have seen pattern welding develop as it did. |

Chad,

I realise thats the conventional wisdom and I understand the 'economic' side of it... I agree that is all true. But that doesn't neccessarily rule out the idea of pattern welded weapons being better quality or more effective.

if we know that homogeneous steel swords and pattern welded swords existed side by side, maybe the latter were actually better. I have certainly read more than one analysis favorably comparing the quality of Celtic swords over Roman ones (contradicting some Roman sources which had it the other way around). We know pattern welding persisted well into the "dark ages", the Vikings did it, even when the Franks were producing homogenous steel swords (if I understand correctly)

Even if a pattern welded sword was better the availablity of cheaper, faster more consistent homogenous steel-smelting techniques would still probably lead to their being phased out.

In other words, to put it in economic terms, if a pattern welded sword was say, twice as effective as an ordinary steel sword, but one out of three pattern welded swords didn't come out right and you could make 3 homogeneous steel swords in the same time that you could make one pattern welded one (which you certainly could by the time the overwash water wheel brought the mill powered bellows and barcelona hammer into the picture in the 11th century or so), one can easily see how pattern welding would dissapear.

And yet, the Vikings and Germanic tribes prized the old style pattern welded swords, there are all sorts of references to "the serpent in the steel" or the "dragon" in the steel. They no doubt appreciated asthetics but they were eminently pragmatic folks also. Thats why swords were made of steel in the first place rather than gold.

Jean

[quote="Jean Henri Chandler"]

As far as I've read, during the Viking period, the Frankish monosteel swords (such as the Ulfberht ones) were highly prized by the Vikings. The Ulfberth swords were even copied, which just shows that they were highly priced in those days. The latest patternwelded swords were basically just monosteel swords, which a decorative patterenwelded layer on it. Then patternwelding was dropped alltogether.

I've also read that at least in case of the early patternwelded swords, they were a combination of hard and brittle phosporous iron, and soft but tough manganese iron. I've never seen metallurgical reports on early medieval swords though. What contradicts this is that higher carbon steels have been available since the iron age. I've read of one iron age high carbon steel sword that was not hardened. Perhaps they didn't have the knowledge yet how to temper until the monosteel blades like te Ulfberth swords? On that subject, does anyone actually have access to metallurgical reports on early medieval swords?

| Quote: |

| Jean,

In other words, to put it in economic terms, if a pattern welded sword was say, twice as effective as an ordinary steel sword, but one out of three pattern welded swords didn't come out right and you could make 3 homogeneous steel swords in the same time that you could make one pattern welded one (which you certainly could by the time the overwash water wheel brought the mill powered bellows and barcelona hammer into the picture in the 11th century or so), one can easily see how pattern welding would dissapear. |

As far as I've read, during the Viking period, the Frankish monosteel swords (such as the Ulfberht ones) were highly prized by the Vikings. The Ulfberth swords were even copied, which just shows that they were highly priced in those days. The latest patternwelded swords were basically just monosteel swords, which a decorative patterenwelded layer on it. Then patternwelding was dropped alltogether.

I've also read that at least in case of the early patternwelded swords, they were a combination of hard and brittle phosporous iron, and soft but tough manganese iron. I've never seen metallurgical reports on early medieval swords though. What contradicts this is that higher carbon steels have been available since the iron age. I've read of one iron age high carbon steel sword that was not hardened. Perhaps they didn't have the knowledge yet how to temper until the monosteel blades like te Ulfberth swords? On that subject, does anyone actually have access to metallurgical reports on early medieval swords?

Alright, I've found some actual information, which answers a lot of questions. It's from "The prehistory of metallurgy in the British Isles" by R.F. Tylecote:

Iron age:

Isleham, UK, 50BC-50AD

- carbon contents: variable

- phosporous contents: 0.01%

- manganese contents: -

- hardness: 320-450 HV (cutting edge 370-450 HV)

Notes: sandwich of three layers, with a higher carbon central layer. Hardness suggests fast aircooling.

Waltham Abbey, UK, ?

- carbon contents: 0-0.25%

- phosporous contents: 0.075%

- manganese contents: 0.0035%

- hardness: 170-250 HV

Notes: 24 piled layers of 0-0.25 %C. 250 HV at edge, 170 HV at core

Other blades: examination of 5 blades from Llyn Cerrig Bach showed 4 piled blades with wrought iron with various degrees in carburization, and one piled at right angle to the axis of the cross-section (linear pattern), with alternating higher and lower carbon contents. All five blades have hardnesses in the 140- 265 HV range, usually higher at the edges and lower at the core.

Other notes: edges sometimes workhardened on the iron age swords.

Roman period:

'N' type Nydam sword, Denmark, first half of 3rd century AD

-Edges: one side 0.29% C, other 0.43% C

-Core: 0.5% C

-Thin iron strips on either side of core: 0.1% C

-Three twisted billets either side of core: 0.1-0.6% C

-Phosphorous contents: 0.16-0.21%

Note: A sword from South Shields, UK (197-205AD) has twist damast as well, with similar bronze inlays as Nydam sword.

Possibly spatha, Whittlesey, 2nd-4th century AD

Section shows well diffused structure of ferrite and pearlite with a higher carbon zone running through its centre, varying from 0.3% C at cutting edge to 0.25% C at center. The carbon contents of the center decreases to about 0.1% C at surfaces. Hardness varies from 120-150 HV.

Early medieval period:

Ulfberht sword, Donnybrook, Dublin, Ireland, ?

Centre:

- carbon contents: 0.2%

- phosporous contents: 0.02%

- manganese contents: 0.1-1.0%

Fine grained ferrite with spheroidal pearlite

Edge:

- carbon contents: 0.3-0.4%

- phosporous contents: trace

- manganese contents: 0.1%

Quench-hardened to 520-550 HV

Notes: piled layout.

French pattern-welded swords:

M. 7 core:

- carbon contents: 0.12%

- phosporous contents: 0.21%

- manganese contents: 0.01%

M. 10 core:

- carbon contents: 0.09%

- phosporous contents: 0.30%

- manganese contents: 0.05%

M.11 core:

- carbon contents: 0.08%

- phosporous contents: 0.16%

- manganese contents: nil

M.11 edge:

- carbon contents: 0.2%

- phosporous contents: 0.14%

- manganese contents: nil

Luneville sword, core:

- carbon contents: 0.01-0.05%

- phosporous contents: 0.18%

- manganese contents: nil

Luneville sword, core:

- carbon contents: 0.02-0.03%

- phosporous contents: -

- manganese contents: -

Three Norwegian pattern welded swords: 0.414% C, 0.401% C and 0.52% C

Ulfberht sword from Norway, 10th century AD: 0.75% C (not patternwelded)

Frankish sword, Canwick Common, 9th-10th century AD:

Piled in 2mm thick layers

Structure varies from high-carbon martensite to lower-carbon structure throughout the structure

Hardness 306-630HV

Pattern-welded sword of Palace of Westminster, UK, 9nd century AD:

Patternwelded areas down the center consist of 0.2% C iron together with fine and coarse grained ferrite and small globules of slag. Hardness 186-188 HV. The edges consist of fine-grained mild steel with a ferrite + pearlite structure, but surprizingly only a hardness of 136- 145 HV. Patternwelded areas are possibly harder due to higher phosphorous contents.

Note:

Story of the batlle at Swanfirth against Snorri and his folk shows that good and bad swords were used concurrently. Steinthor found that "the fair-wrought sword bit not whenas it smote armour, and oft he must straighten it under his foot"

The book also contains some information on axes, knives and scramaseaxes. But I'm too tired at the moment to write that all down.

Iron age:

Isleham, UK, 50BC-50AD

- carbon contents: variable

- phosporous contents: 0.01%

- manganese contents: -

- hardness: 320-450 HV (cutting edge 370-450 HV)

Notes: sandwich of three layers, with a higher carbon central layer. Hardness suggests fast aircooling.

Waltham Abbey, UK, ?

- carbon contents: 0-0.25%

- phosporous contents: 0.075%

- manganese contents: 0.0035%

- hardness: 170-250 HV

Notes: 24 piled layers of 0-0.25 %C. 250 HV at edge, 170 HV at core

Other blades: examination of 5 blades from Llyn Cerrig Bach showed 4 piled blades with wrought iron with various degrees in carburization, and one piled at right angle to the axis of the cross-section (linear pattern), with alternating higher and lower carbon contents. All five blades have hardnesses in the 140- 265 HV range, usually higher at the edges and lower at the core.

Other notes: edges sometimes workhardened on the iron age swords.

Roman period:

'N' type Nydam sword, Denmark, first half of 3rd century AD

-Edges: one side 0.29% C, other 0.43% C

-Core: 0.5% C

-Thin iron strips on either side of core: 0.1% C

-Three twisted billets either side of core: 0.1-0.6% C

-Phosphorous contents: 0.16-0.21%

Note: A sword from South Shields, UK (197-205AD) has twist damast as well, with similar bronze inlays as Nydam sword.

Possibly spatha, Whittlesey, 2nd-4th century AD

Section shows well diffused structure of ferrite and pearlite with a higher carbon zone running through its centre, varying from 0.3% C at cutting edge to 0.25% C at center. The carbon contents of the center decreases to about 0.1% C at surfaces. Hardness varies from 120-150 HV.

Early medieval period:

Ulfberht sword, Donnybrook, Dublin, Ireland, ?

Centre:

- carbon contents: 0.2%

- phosporous contents: 0.02%

- manganese contents: 0.1-1.0%

Fine grained ferrite with spheroidal pearlite

Edge:

- carbon contents: 0.3-0.4%

- phosporous contents: trace

- manganese contents: 0.1%

Quench-hardened to 520-550 HV

Notes: piled layout.

French pattern-welded swords:

M. 7 core:

- carbon contents: 0.12%

- phosporous contents: 0.21%

- manganese contents: 0.01%

M. 10 core:

- carbon contents: 0.09%

- phosporous contents: 0.30%

- manganese contents: 0.05%

M.11 core:

- carbon contents: 0.08%

- phosporous contents: 0.16%

- manganese contents: nil

M.11 edge:

- carbon contents: 0.2%

- phosporous contents: 0.14%

- manganese contents: nil

Luneville sword, core:

- carbon contents: 0.01-0.05%

- phosporous contents: 0.18%

- manganese contents: nil

Luneville sword, core:

- carbon contents: 0.02-0.03%

- phosporous contents: -

- manganese contents: -

Three Norwegian pattern welded swords: 0.414% C, 0.401% C and 0.52% C

Ulfberht sword from Norway, 10th century AD: 0.75% C (not patternwelded)

Frankish sword, Canwick Common, 9th-10th century AD:

Piled in 2mm thick layers

Structure varies from high-carbon martensite to lower-carbon structure throughout the structure

Hardness 306-630HV

Pattern-welded sword of Palace of Westminster, UK, 9nd century AD:

Patternwelded areas down the center consist of 0.2% C iron together with fine and coarse grained ferrite and small globules of slag. Hardness 186-188 HV. The edges consist of fine-grained mild steel with a ferrite + pearlite structure, but surprizingly only a hardness of 136- 145 HV. Patternwelded areas are possibly harder due to higher phosphorous contents.

Note:

Story of the batlle at Swanfirth against Snorri and his folk shows that good and bad swords were used concurrently. Steinthor found that "the fair-wrought sword bit not whenas it smote armour, and oft he must straighten it under his foot"

The book also contains some information on axes, knives and scramaseaxes. But I'm too tired at the moment to write that all down.

| Russel Foxtrot wrote: |

| ...I wondered just how advanced the sword making techniques were of the groups that inhabited the British Isles during the Dark Ages. I understand that the Romans perhaps brought some continuity in manufacture to the inhabitants of Britain but I'm also aware that before the Roman Conquest sword manufacture has apparently been found to be inferior to that practiced by the Celts on the continent and so I'm quite interested in knowing about the techniques of groups such as the Picts and Scotti who remained relatively untouched if anyones has information. As this was the time of high point of pattern welded swords and the introduction of better steel (from the likes of Catalonia) how did swords compare with those on the continent? |

Hi Russel...

Welcome to myArmoury!

Let me give you my 2 cents mainly from memory of things I have read in the past (or things I think I read somewhere :D )

Feel free to correct me ;)

In the Dark Ages:

Kent, in southern England, was a center of iron working and possessed some of the best blades. A high percentage, over half I believe, of the swords found in the burials in Kent were pattern welded and of superior quality (by the standards of the day, not today's standards). Or maybe we could say superior quality in terms of the "bling" factor (very fine looking), but only better than average in terms of performance. And then there was the ever present and persistent quality control problems. The forge was much more magical than scientific. )For instance it was not until well into the Industrial Age when the idea of carbon migration was developed. Before that time it was either some strange magic of the god's that made the blade tougher or, it was some form of alchemy that cleansed the iron of some impurity.)

Moving northward from Kent to Scotland and then to Ireland blades became progressively shorter and poorer in quality with much less evidence of pattern-welding.

It is logical to suppose this difference is due to Roman influence, southern Britain was a Roman provence (britannia). And there are even theories on Roman estates that controlled the forges in these areas. However, there are other possibilites. For instance (and I just made this up off the top of my head) there could have been more emphasis on the sword and its use as a prestige item in the south as opposed to the north. I think Jeff may have mentioned this earlier in reference to preservation. Prestige items would be kept longer and preserved. (It should also be kept in mind that this southern Kentish connection of sword manufacture and/or continental cultural migration seems to predate the Romans. If I remember correctly Bronze Age and Celtic sword finds also suggests the same trends from south to north. )

I have also heard that the Romans may have imported finer steels from the east, though I can't remember seeing any textural evidence for this. Even if finer eastern steels made it to the Roman Empire it is unlikely it would make it to the edge of the frontiers in the far Western Empire.

The idea that pattern welding was primarily decorative is not the leading view for no reason. For instance as pattern welding begins to disappear, archeologists find blades with pattern welded inlays and veneers on monosteel blades does suggest the possibility that pattern welding was much more decorative than functional. However this argument is really quite strained. The opponents can counter that pattern welding had been so long associated with better quality blades it had become a trademark and when truly superior blades appeared people would not believe they really were superior with out the old trademark in the form of pattern welded inlays and veneers.

ks

Hi again...

Just after I posted, I saw the data Jeroen provided and it reminded me I had seen a summary of some R.F. tylecote's conclusions as well as many other researches in this area. I found it in a work by Janet Lang and Barry Ager entitled "Swords of the Anglo-Saxon and Viking periods in the British Museum: a radiographic study", in Weapons and Warfare in Anglo-Saxon England edited by SC hawkes (Oxford, 1989).

(Be warned this is more of the "consensus." However, keep in mind it is the consensus of men and women who have spent their careers studying this very question.)

This is what it says:

"Pattern -welding has been considered to have been employed mainly for strengthening the blade, but some recent papers suggest rather that it was used mainly for decoration and a consensus of opinion seems to be gradually emerging to this effect. tylecote (1962 p. 250) remarked that the pattern was a by-product of the method of manufacture and not an intended effect. It was used, he suggested, to introduce carbon into the blade to a greater depth and thus to increase its hardness. At the same time the embrittling effect concomitant with increasing hardness would be mitigated by the softer tougher strips also incorporated in the pattern-welded structure, and gross slag inclusions would be also eliminated. Later, however, Tylecote (1976, p.57) has commented that it is not clear that artifacts made in this way were appreciably stronger than most of the weapons made by simple piling, but if well polished, they would look beautiful. Most recently (1986), Tylecote said that the pattern-welded sword appears to have been designed in its earliest phase as an ornamental or prestige weapon and its military usefulness seems to have taken second place to its appearance. He adds 'if it were not for the fact that we know that such swords were used for fighting (Beowulf etc) we would have supposed that its purpose was like the ceremonial sword of today.'

Some early work supported the idea that the swords had superior properties; certainly Salin (1957) and France-Lanord (1947) found that the patter-welded swords which they examined were extremely hard and apparently could cut like razors. France-Lanord (1947) also tested the blades he was examining and found that pattern-welded blades were three times more flexible than ordinary blades (Salin 1957, p. 65)...

During conservation in the British Museum Conservation workshop a seventh-century pattern-welded sword in good condition from Acklam still exhibited considerable springiness when being straightened in spite of lying in the ground for fourteen centuries. Menghin (1983) also stressed the importance of pattern-welding and the resilience of the blade.

Although the resilience of the blade is important, pattern-welding is not necessarily the best way of achieving it. Ypey (1984), as a result of his own experimental work, has suggested that the purpose of pattern-welding was almost entirely decorative, at least in the later Carolingian and Viking periods. This must be the case with pattern-welded spearheads which are of rigid construction. Menghin (1983) has reported thin surface layers of pattern-welded material on sword blades which must be also entirely decorative, although it should not be forgotten that these developments are relatively late. So may swords have been identified as having three layers, a relatively plain layer (Schurmann 1959) between two pattern-welded ones, that it is difficult to believe that their presence is entirely functional. Cutting edges and cores were constructed from more than one strip (Schurmann 1959, Tylecote 1986) but often with a layered structure, and this was probably intended for strengthening. Gilmour (Tylecote 1986) sectioned a number of pattern-welded swords and found that the blades were variable both in relation to soundness and their hardness although there seemed to be a technical improvement from the eighth century onwards. The majority were made from wrought iron, both phosphorus rich and phosphorus free, while some contained some iron richer in carbon. Gilmour discussed the use of phosphorus iron, which he concluded was employed to improve the pattern, rather than for its structural properties. Phosphorus iron was frequently used during the Iron Age (Schultz 1965) and a Roman blowing iron was constructed from low and high phosphorus irons. In this case it was concluded(following Rollason 1978, 170) that these irons were used to facilitate welding (Lang 1976). If this were the case, it might have been a factor in its use in pattern-welding. Goodway (1987) also points out that phosphorus has a considerably hardening effect and in the absence of carbon can be worded and used satisfactorily. On balance it seems most likely that pattern-welding was largely decorational. It is quite possible that pattern-welding was thought to improve the properties of the swords, and might be remembered that a smith with the skill to produce fine pattern-welding might be likely to produce a good quality sword anyway."

[You will notice I left out a small part of the text. This is because it dealt with period textual evidence and I wanted to focus on research of the actual swords.]

One thing I noticed with Tylecote's work is that there should be a distinction between the act of pattern welding of the core, which gets all the attention and the amazing inclusion of high carbon steel for the edges which gets very little attention. While it may be that the layers of the Pattern-Welded core do not necessarily make for a better sword (only prettier), the high carbon steel edges certainly would add to its cutting quality. Also notice that the use of phosphorus iron would explain why the swords Tylecote examined showed signs or workhardening... I have heard that phosphorus iron can be work hardened like bronze.

hope this helps

ks

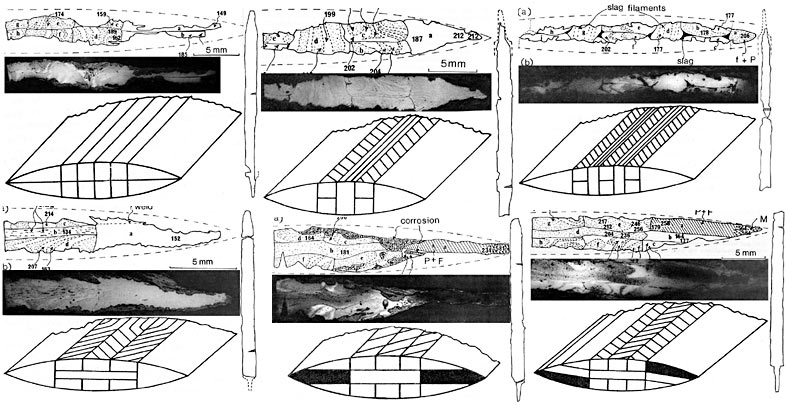

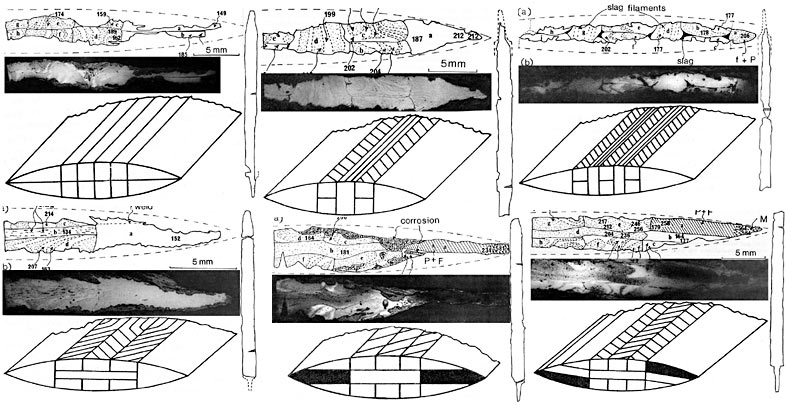

Attachment: 98.26 KB

Attachment: 98.26 KB

A selection of pattern-welded blades from Kent compiled from "The Metallography of Early Ferrous Edge Tools & Edged Weapons" by R.F. Tylecote & B.J.J.Gilmour

Just after I posted, I saw the data Jeroen provided and it reminded me I had seen a summary of some R.F. tylecote's conclusions as well as many other researches in this area. I found it in a work by Janet Lang and Barry Ager entitled "Swords of the Anglo-Saxon and Viking periods in the British Museum: a radiographic study", in Weapons and Warfare in Anglo-Saxon England edited by SC hawkes (Oxford, 1989).

(Be warned this is more of the "consensus." However, keep in mind it is the consensus of men and women who have spent their careers studying this very question.)

This is what it says:

"Pattern -welding has been considered to have been employed mainly for strengthening the blade, but some recent papers suggest rather that it was used mainly for decoration and a consensus of opinion seems to be gradually emerging to this effect. tylecote (1962 p. 250) remarked that the pattern was a by-product of the method of manufacture and not an intended effect. It was used, he suggested, to introduce carbon into the blade to a greater depth and thus to increase its hardness. At the same time the embrittling effect concomitant with increasing hardness would be mitigated by the softer tougher strips also incorporated in the pattern-welded structure, and gross slag inclusions would be also eliminated. Later, however, Tylecote (1976, p.57) has commented that it is not clear that artifacts made in this way were appreciably stronger than most of the weapons made by simple piling, but if well polished, they would look beautiful. Most recently (1986), Tylecote said that the pattern-welded sword appears to have been designed in its earliest phase as an ornamental or prestige weapon and its military usefulness seems to have taken second place to its appearance. He adds 'if it were not for the fact that we know that such swords were used for fighting (Beowulf etc) we would have supposed that its purpose was like the ceremonial sword of today.'

Some early work supported the idea that the swords had superior properties; certainly Salin (1957) and France-Lanord (1947) found that the patter-welded swords which they examined were extremely hard and apparently could cut like razors. France-Lanord (1947) also tested the blades he was examining and found that pattern-welded blades were three times more flexible than ordinary blades (Salin 1957, p. 65)...

During conservation in the British Museum Conservation workshop a seventh-century pattern-welded sword in good condition from Acklam still exhibited considerable springiness when being straightened in spite of lying in the ground for fourteen centuries. Menghin (1983) also stressed the importance of pattern-welding and the resilience of the blade.

Although the resilience of the blade is important, pattern-welding is not necessarily the best way of achieving it. Ypey (1984), as a result of his own experimental work, has suggested that the purpose of pattern-welding was almost entirely decorative, at least in the later Carolingian and Viking periods. This must be the case with pattern-welded spearheads which are of rigid construction. Menghin (1983) has reported thin surface layers of pattern-welded material on sword blades which must be also entirely decorative, although it should not be forgotten that these developments are relatively late. So may swords have been identified as having three layers, a relatively plain layer (Schurmann 1959) between two pattern-welded ones, that it is difficult to believe that their presence is entirely functional. Cutting edges and cores were constructed from more than one strip (Schurmann 1959, Tylecote 1986) but often with a layered structure, and this was probably intended for strengthening. Gilmour (Tylecote 1986) sectioned a number of pattern-welded swords and found that the blades were variable both in relation to soundness and their hardness although there seemed to be a technical improvement from the eighth century onwards. The majority were made from wrought iron, both phosphorus rich and phosphorus free, while some contained some iron richer in carbon. Gilmour discussed the use of phosphorus iron, which he concluded was employed to improve the pattern, rather than for its structural properties. Phosphorus iron was frequently used during the Iron Age (Schultz 1965) and a Roman blowing iron was constructed from low and high phosphorus irons. In this case it was concluded(following Rollason 1978, 170) that these irons were used to facilitate welding (Lang 1976). If this were the case, it might have been a factor in its use in pattern-welding. Goodway (1987) also points out that phosphorus has a considerably hardening effect and in the absence of carbon can be worded and used satisfactorily. On balance it seems most likely that pattern-welding was largely decorational. It is quite possible that pattern-welding was thought to improve the properties of the swords, and might be remembered that a smith with the skill to produce fine pattern-welding might be likely to produce a good quality sword anyway."

[You will notice I left out a small part of the text. This is because it dealt with period textual evidence and I wanted to focus on research of the actual swords.]

One thing I noticed with Tylecote's work is that there should be a distinction between the act of pattern welding of the core, which gets all the attention and the amazing inclusion of high carbon steel for the edges which gets very little attention. While it may be that the layers of the Pattern-Welded core do not necessarily make for a better sword (only prettier), the high carbon steel edges certainly would add to its cutting quality. Also notice that the use of phosphorus iron would explain why the swords Tylecote examined showed signs or workhardening... I have heard that phosphorus iron can be work hardened like bronze.

hope this helps

ks

A selection of pattern-welded blades from Kent compiled from "The Metallography of Early Ferrous Edge Tools & Edged Weapons" by R.F. Tylecote & B.J.J.Gilmour

I am going to weigh in a little with theory over why pattern welding may have been done, and why the twisted serpent form could have been prevalent.

Some facts first,

1) Ores were exported in the form of ingots (often Wootz originating from India, but commonly known for being worked in Damascus.) Ores were also traded in iron-steel rods of varying quality. Some materials such as the Wootz had carbon content as high as 1.5% which is excellent for hard tool steel, but were not ideal for a spring temper which should be closer to 1% carbon than 1.5%. This was taking place in "B.C." era.

2) Some blacksmith tools of Anglo Saxon "Dark Ages" period are known. One excavated site clearly showed that the anvil was a mere stake anvil (a spike like object wedged into a stump) and relatively small fire composed of ring of stones on a sand bed. The hammer was comparable to a modern 4 to 6 lb one.

3) The process of forge welding with moderate time and adequate welding temperature causes carbon to diffuse between high and low carbon steels to a degree, but much of it is simply lost, quickly! Modern pattern welders often utilize very heavy "power hammer" machinery to make large cross sectional rectangular bars of pattern welded material all at once without loosing too much carbon. If working the metal by hand, it is better to work in smaller pieces such as rods so that human force can perform the welds and draw or stretch back out to a shape if part of an elaborate pattern. It is also possible to only heat a small section to the temperature of welding, if working with a small fire and small cross section pieces, without loosing too much carbon. A 1/2" to 3/4" square twisted rod can be done with a hand held hammer and modest sized anvil. This was actually demonstrated by a blacksmith that fully completed a nice pattern welded sword blank in 315 hammer strokes from start to unground finish with mixed composition rods on the History Channel Show "Meet the Ancestor, Warrior", who was described as "Anglo Saxon." Considering that this allowed for creation of 4 subsections and the final welding of them into one sword blank, that works out to a manageable 75 hammer blows per twisted rod or stacked strip assembly. About 6 to 7 blows is all that can typically be done before the metal cools below welding temperature, so the rod has to be shoved back into the fire with the next section to be welded in the "heart of the fire" about 10 times to complete it as a major segment of the completed sword still relatively high in carbon content.

My "Theory"

I suspect pattern welded swords with the twisted rod core and stacked layer edge prevailed because this was conducive to the tools, and economy of using higher and lower carbon grade available materials. As few as three successive cycles (locally at each section of metal that reached temperatures of carbon diffusion) of heating to forge welding temperatures could have been done with the available materials to arrive at completed sword blanks (still unground.) Rods of varying quality could have been sorted by known origin, appearance, and possibly simple tests of hardness and ductility so as to match up layers of esthetic and functional performance in finished twisted rods and stacked bars of strips (made from flattened rods.) The probability of successful welds with mere hand tools would have been better if limited to modest diameter/ square cross section rods and strips.

I call this "my theory", but I happen to have a mentor that has produced a significant amount of pattern welded material at first by hand, then later with the power or trip hammer. He is fanatical about testing remper results for Rockwell hardness, and insists that results of handwork will turn out inconsistent (too low in carbon) unless the cross section is kept small as we see in most historical examples.

Some facts first,

1) Ores were exported in the form of ingots (often Wootz originating from India, but commonly known for being worked in Damascus.) Ores were also traded in iron-steel rods of varying quality. Some materials such as the Wootz had carbon content as high as 1.5% which is excellent for hard tool steel, but were not ideal for a spring temper which should be closer to 1% carbon than 1.5%. This was taking place in "B.C." era.

2) Some blacksmith tools of Anglo Saxon "Dark Ages" period are known. One excavated site clearly showed that the anvil was a mere stake anvil (a spike like object wedged into a stump) and relatively small fire composed of ring of stones on a sand bed. The hammer was comparable to a modern 4 to 6 lb one.

3) The process of forge welding with moderate time and adequate welding temperature causes carbon to diffuse between high and low carbon steels to a degree, but much of it is simply lost, quickly! Modern pattern welders often utilize very heavy "power hammer" machinery to make large cross sectional rectangular bars of pattern welded material all at once without loosing too much carbon. If working the metal by hand, it is better to work in smaller pieces such as rods so that human force can perform the welds and draw or stretch back out to a shape if part of an elaborate pattern. It is also possible to only heat a small section to the temperature of welding, if working with a small fire and small cross section pieces, without loosing too much carbon. A 1/2" to 3/4" square twisted rod can be done with a hand held hammer and modest sized anvil. This was actually demonstrated by a blacksmith that fully completed a nice pattern welded sword blank in 315 hammer strokes from start to unground finish with mixed composition rods on the History Channel Show "Meet the Ancestor, Warrior", who was described as "Anglo Saxon." Considering that this allowed for creation of 4 subsections and the final welding of them into one sword blank, that works out to a manageable 75 hammer blows per twisted rod or stacked strip assembly. About 6 to 7 blows is all that can typically be done before the metal cools below welding temperature, so the rod has to be shoved back into the fire with the next section to be welded in the "heart of the fire" about 10 times to complete it as a major segment of the completed sword still relatively high in carbon content.

My "Theory"

I suspect pattern welded swords with the twisted rod core and stacked layer edge prevailed because this was conducive to the tools, and economy of using higher and lower carbon grade available materials. As few as three successive cycles (locally at each section of metal that reached temperatures of carbon diffusion) of heating to forge welding temperatures could have been done with the available materials to arrive at completed sword blanks (still unground.) Rods of varying quality could have been sorted by known origin, appearance, and possibly simple tests of hardness and ductility so as to match up layers of esthetic and functional performance in finished twisted rods and stacked bars of strips (made from flattened rods.) The probability of successful welds with mere hand tools would have been better if limited to modest diameter/ square cross section rods and strips.

I call this "my theory", but I happen to have a mentor that has produced a significant amount of pattern welded material at first by hand, then later with the power or trip hammer. He is fanatical about testing remper results for Rockwell hardness, and insists that results of handwork will turn out inconsistent (too low in carbon) unless the cross section is kept small as we see in most historical examples.

Page 1 of 3

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum