The Ochs dvds are certainly a very interesting source. It's hard to really understand to mechanic of the fight simply by reading a book (for me at least).

You might also want to take a look at youtube.com and search for "longsword", "western martial arts", etc. Not everything is bad there. ;)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y3DhjFUOG6Y

Concerning the greatsword and the longsword, in my own experience, the later appears more lively in the hand, allowing to stop in mid cut without effort to do a parry-estoc, while the first can get you tired fast if you try to use it this way. The best with the great cutting swords (one or two-handed) is to simply redirect the energy of the cut, instead of "fighting" it. This way you can fight with a greatsword for a long time without breaking a sweat... Well, my point is that a greatsword can appears somewhat heavy and ponderous if not used in the way it's meant to be. Different tools handle differently.

Hello again!

Hugo,

That sounds similar to what Oakeshott said regarding the 12th, 13th and 14th century great sword; "if handled correctly, (it) handles well". He also pointed out that they were made for a specific purpose.

I think one point we must keep in mind is that these swords ceased to be popular toward the later part of the 14th century; there were better tools out there that could do the job more efficiently. They did become popular again during the later part of the 15th century, but I'm not sure how widespread that popularity was, and these examples may have been designed for a different purpose than the earlier examples. The great swords of the 12th-14th centuries may have been designed to defeat mail and reinforced mail armour, while the 15th century examples may have been designed against lightly armoured foes. My point is, a knight of the late 14th century might choose a XVa over the older XIIIa, because the XVa might have done the job better at that time. It could more effectively exploit gaps in the plate armour, and it might feel "livelier" in the hand. Just pondering the possibilities!

Stay safe!

| Hugo Voisine wrote: |

|

Well, my point is that a greatsword can appears somewhat heavy and ponderous if not used in the way it's meant to be. Different tools handle differently. |

Hugo,

That sounds similar to what Oakeshott said regarding the 12th, 13th and 14th century great sword; "if handled correctly, (it) handles well". He also pointed out that they were made for a specific purpose.

I think one point we must keep in mind is that these swords ceased to be popular toward the later part of the 14th century; there were better tools out there that could do the job more efficiently. They did become popular again during the later part of the 15th century, but I'm not sure how widespread that popularity was, and these examples may have been designed for a different purpose than the earlier examples. The great swords of the 12th-14th centuries may have been designed to defeat mail and reinforced mail armour, while the 15th century examples may have been designed against lightly armoured foes. My point is, a knight of the late 14th century might choose a XVa over the older XIIIa, because the XVa might have done the job better at that time. It could more effectively exploit gaps in the plate armour, and it might feel "livelier" in the hand. Just pondering the possibilities!

Stay safe!

| Richard Fay wrote: |

|

Thanks for the observations, and the stats on the two period examples! This was very illuminating information! So, if I'm reading this correctly, some XIIIa'a were relatively "slower" and more "ponderous" than others (sorry for using these terms again, Patrick, but I'm just quoting here). I wonder if the "heavier" sword was designed as more of an "anti-armour" weapon, and the "lighter" sword was more to be used against lightly armoured or unarmoured foes. Or maybe one swordsmith just got it right, and another got it wrong. When you say some swords handle like crowbars, are you referring to modern reproductions only, or do some period examples handle like that? I know some modern reproductions can handle badly; I had a Windlass sword when MRL first switched over, and it was very tip-heavy, and definitely ponderous! Are you saying some period examples might not handle in what most feel is an "ideal" fashion? I'm just trying to make sure I understand you clearly. It seems like that's what the stats you posted would indicate. This is along the lines of what I've been trying to say, but I've only really had Oakeshott's observations to work on. I believe that there could be some variation in period examples; Oakeshott seemed to observe that some type XIIIa's felt light and well-balanced, while others felt relatively heavy. Medieval swordsmiths were master craftsmen, but they were human, and some period swords do seem to have better dynamic properties than others, at least based on my interpretation of Oakeshott's observations. I know modern customers want the finest blade their money can buy, and they should get just that, but it might not have always been the case with every period example. (Oakeshott showed a type XVIIIa with a significant forge-made bend in the blade. This would be considered a far from perfect blade today. It's XVIIIa. 2 in Records of the Medieval Sword.) I think medieval warriors may sometimes have looked for different things in their blades than modern customers do today. A heavier sword may have been ideal for a well-armoured knight who fought other well-armoured knights on horseback, but it might be far from ideal for a modern practitioner of western martial arts. That doesn't mean that finely-crafted, well-balanced, easily-wielded great swords didn't exist, it just means that different swords were made for different purposes. Of course, it's all relative, and even the heavier examples would have been fairly well-balanced, or the medieval warrior would have rejected it! Still, the examples that Angus presented, as well as the two type XVII's that Oakeshott discussed (the one he owned, and the one in the Fitzwilliam Museum) show that different swords of the same type could have different handling characteristics. Some might feel that certain swords are heavier than others, but it's all relative, as well as subjective. I Stay safe! |

HI Richard

The only reason I got involved in this thread, is this site is widely considered an educational site. A good place to learn more about swords, and the properties thereof....

I thought that without interjecting something, that a distorted picture of our history could result for some readers. This is a subject that inspires incredible passions, and when we speak with those passions fired up, we can leave a bit of a one sided view "up". But these discussions wind up being accessed for years afterwards........thus I feel it important to sometimes interject a differing view on things.....

I could make a good case for most of the early types {X, XI, XII, XIII, XIIIa} being "boat anchors", because the center of gravity of many of these is quite a ways down the blade, but there are also early versions that handle like "magic".......And some inbetween.......

The point being that making a case for one or the other, is ignoring the fact that there is tremendous variability in these antiques. I think it important to interject that a truly balanced view may be impossible, because there are really, very few survivors from "period". Thus, sometimes the best thing to do is keep an open mind.........

In the subject of swords, when thinking in terms of stereotypes, one should always "caveat". In this thread for instance, its been suggested that the later "longswords" were more "handy". I think that, as a generalization that may be true, but in the Oakeshott collection there's an XVIIIa {XVIIIb if "Swords in the Age of Chivalry is used for typology} with a cog of 9 inches, and its handling has been described in less than complimentary terms by at least one WMA gent that has handled it.....

Hello all!

Angus,

Your input is greatly appreciated, at least by me! Like I mentioned earlier, I have not had the chance to handle period pieces (or even higher quality reproductions), so I have to rely on what Oakeshott and others (like you) have said about the handling of period pieces. It's not the best way to gain an understanding about these things, I know, but it's the way I have at the moment.

I, too, believe that this site serves a valuable educational purpose; that's why I post extremely long excerpts from various books, to broaden knowledge. I know book learning can only take you so far, but books are valuable resources.

I hope I wasn't presenting a distorted picture by my arguments and quotes; that wasn't my intention! I, too, am passionate about this subject, but also try to approach it with an open mind, and cover all aspects of it (at least, all aspects I can within my means). I think we feel the same about this issue, even if we are approaching it from different angles; different period swords even of the same type could have different handling properties. Again, I am aware that calling the later longswords more "wieldy" is a generality. Of course there are exceptions to every rule; but I think that the tapered edges and other properties would make a later longsword handle a bit sweeter than a parallel-edged great sword of the same size. I know there are many, many other factors involved here, and maybe it is a gross over-simplification.

I hope my posts have sounded thoughtful, even if I do lack practical knowledge. I've tried to discuss both sides of the issue, but perhaps I spent a bit more time on "heavier" great swords, because that was the main point of my comments. It was also the point of contention in what I said, so maybe I did get a bit one-sided for awhile. Some of the questions surrounding what I said were just about the verbiage, one of the negative points about internet communications (and my habit of relying heavily on Oakeshott).

I think I've been trying to say that there is variability amongst antiques, at least based on what I've read. Handmade objects are rarely exactly the same; there is always some variability because of the human element. Add to that different tools for different uses, and different preferences by different users, and you can have an almost limitless amount of variability.

Again, Angus, I really appreciate that you interjected your thoughts and experiences. That's just the sort of thing I was looking for!

Thanks again for the input! I would love to read more, if you get a chance!

By the way, do you know if that XVIIIa with a COG of 9 inches is in Records of the Medieval Sword, and if so, which number? If it is, I could post a picture. (Also, I would like to read what Oakeshott said about it.)

Stay safe!

| Angus Trim wrote: |

|

The only reason I got involved in this thread, is this site is widely considered an educational site. A good place to learn more about swords, and the properties thereof.... I thought that without interjecting something, that a distorted picture of our history could result for some readers. |

Angus,

Your input is greatly appreciated, at least by me! Like I mentioned earlier, I have not had the chance to handle period pieces (or even higher quality reproductions), so I have to rely on what Oakeshott and others (like you) have said about the handling of period pieces. It's not the best way to gain an understanding about these things, I know, but it's the way I have at the moment.

I, too, believe that this site serves a valuable educational purpose; that's why I post extremely long excerpts from various books, to broaden knowledge. I know book learning can only take you so far, but books are valuable resources.

I hope I wasn't presenting a distorted picture by my arguments and quotes; that wasn't my intention! I, too, am passionate about this subject, but also try to approach it with an open mind, and cover all aspects of it (at least, all aspects I can within my means). I think we feel the same about this issue, even if we are approaching it from different angles; different period swords even of the same type could have different handling properties. Again, I am aware that calling the later longswords more "wieldy" is a generality. Of course there are exceptions to every rule; but I think that the tapered edges and other properties would make a later longsword handle a bit sweeter than a parallel-edged great sword of the same size. I know there are many, many other factors involved here, and maybe it is a gross over-simplification.

I hope my posts have sounded thoughtful, even if I do lack practical knowledge. I've tried to discuss both sides of the issue, but perhaps I spent a bit more time on "heavier" great swords, because that was the main point of my comments. It was also the point of contention in what I said, so maybe I did get a bit one-sided for awhile. Some of the questions surrounding what I said were just about the verbiage, one of the negative points about internet communications (and my habit of relying heavily on Oakeshott).

I think I've been trying to say that there is variability amongst antiques, at least based on what I've read. Handmade objects are rarely exactly the same; there is always some variability because of the human element. Add to that different tools for different uses, and different preferences by different users, and you can have an almost limitless amount of variability.

Again, Angus, I really appreciate that you interjected your thoughts and experiences. That's just the sort of thing I was looking for!

Thanks again for the input! I would love to read more, if you get a chance!

By the way, do you know if that XVIIIa with a COG of 9 inches is in Records of the Medieval Sword, and if so, which number? If it is, I could post a picture. (Also, I would like to read what Oakeshott said about it.)

Stay safe!

Richard,

Gus has mentioned some very valid points. However, I believe he may be misconstruing some of what I was trying to say. When I mention the common properties of these swords I'm not talking about the simplistic terms of static weight, length, width, etc. As Gus has pointed out, these are all merely pieces of the larger puzzle that all need to fit together. In my mind, it would be misleading to call a sword like this a "butt anchor" because the point of balance is far out on the blade. Due to their design many of these swords should have their point of balance out there in order to do their job. Their design follows their intended function and they shouldn't be expected to balance like fishing rods. However, there is a big difference between a sword, both old and new, that has been designed with a purpose and one that has simply been designed badly. Gus' own work is an excellent example of this. He designs each of his swords with a specific goal in mind, because of this the sword will feature specific statistics that lend themselves to that purpose. This is far different from some of the lower end replicas that seem to have been designed with a "let's see what happens" approach. This is what I mean when I talk about the properties of medieval swords. (I don't make them like Gus but I have seen more than a few) Regardless of their feel they generally seem to have been designed with a specific goal in mind, not in the haphazard fashion that terms like "boat anchor", slow and ponderous", heavy", etc. would imply. There were bad swords made then just as now and I've seen a couple that I wouldn't have considered stellar examples but they seem to be in the surviving minority.

I don't really know if that makes it any clearer or not!

Gus has mentioned some very valid points. However, I believe he may be misconstruing some of what I was trying to say. When I mention the common properties of these swords I'm not talking about the simplistic terms of static weight, length, width, etc. As Gus has pointed out, these are all merely pieces of the larger puzzle that all need to fit together. In my mind, it would be misleading to call a sword like this a "butt anchor" because the point of balance is far out on the blade. Due to their design many of these swords should have their point of balance out there in order to do their job. Their design follows their intended function and they shouldn't be expected to balance like fishing rods. However, there is a big difference between a sword, both old and new, that has been designed with a purpose and one that has simply been designed badly. Gus' own work is an excellent example of this. He designs each of his swords with a specific goal in mind, because of this the sword will feature specific statistics that lend themselves to that purpose. This is far different from some of the lower end replicas that seem to have been designed with a "let's see what happens" approach. This is what I mean when I talk about the properties of medieval swords. (I don't make them like Gus but I have seen more than a few) Regardless of their feel they generally seem to have been designed with a specific goal in mind, not in the haphazard fashion that terms like "boat anchor", slow and ponderous", heavy", etc. would imply. There were bad swords made then just as now and I've seen a couple that I wouldn't have considered stellar examples but they seem to be in the surviving minority.

I don't really know if that makes it any clearer or not!

| Patrick Kelly wrote: |

| Richard,

Gus has mentioned some very valid points. However, I believe he may be misconstruing some of what I was trying to say. When I mention the common properties of these swords I'm not talking about the simplistic terms of static weight, length, width, etc. As Gus has pointed out, these are all merely pieces of the larger puzzle that all need to fit together. In my mind, it would be misleading to call a sword like this a "butt anchor" because the point of balance is far out on the blade. Due to their design many of these swords should have their point of balance out there in order to do their job. Their design follows their intended function and they shouldn't be expected to balance like fishing rods. However, there is a big difference between a sword, both old and new, that has been designed with a purpose and one that has simply been designed badly. Gus' own work is an excellent example of this. He designs each of his swords with a specific goal in mind, because of this the sword will feature specific statistics that lend themselves to that purpose. This is far different from some of the lower end replicas that seem to have been designed with a "let's see what happens" approach. This is what I mean when I talk about the properties of medieval swords. (I don't make them like Gus but I have seen more than a few) Regardless of their feel they generally seem to have been designed with a specific goal in mind, not in the haphazard fashion that terms like "boat anchor", slow and ponderous", heavy", etc. would imply. There were bad swords made then just as now and I've seen a couple that I wouldn't have considered stellar examples but they seem to be in the surviving minority. I don't really know if that makes it any clearer or not! |

Hi Patrick

I was trying real careful like not to make it look like I was coming to any conclusions..... merely trying to widen the scope of it a bit......

We have two gents that sometimes grace this board with their presence, who I consider "experts", or historians of the sword, the Johnson twins {Craig and Peter}........ but even in their cases sometimes what is written in one of these discussions can be a bit misleading........ These are ongoing discussions that are quite often spur of the moment kind of things, that many of us would write differently if we knew that what we are writing was going to be around for years, and influence a lot of folks.........

I also think there's a danger of comparing any modern made sword that is not specifically a replica of an existing antique, as an "average" "example" of anything period. That's not to judge the value of any given modern sword, nor how or where they would fit into the past, given time machine access........

I guess I was trying to suggest a bit of caution when writing about historical objects, or even modern ones and whether they are "good" examples, or "bad" examples. There is so much variation in antique blade geometries, that making strong statements as fact, instead of caveating as opinion, can leave lasting impressions that might not necessarily be accurate.

You'll notice some of the most experienced folk these days writing a lot of caveats, and using "opinion" in what they write, because they've discovered how hard it is to be accurate all the time with a statement that looks like fact.......

Craig Johnson is a good example of that................the more he learns, the more he knows, the more he caveats........

Hello again!

Angus and Patrick,

I appreciate input from both you guys, and I can see both sides of the issue. Some of this may be related to perceptions; I believe both of you may have talked about this stuff being rather subjective in nature.

I am not trying to say one sword type is good, or another is bad, I'm just trying to understand the variability of period examples. I have mentioned many times that I think there was a variability in the way swords even of the same type may handle, and both of you have mentioned this, too.

Patrick, you mentioned the fact that the fitness and training of medieval warriors was a factor in how they may have perceived period swords as compared to us moderns. I believe this is definitely an issue with some of the "heavier" and "more massive" great swords. Some were designed specifically to deliver weighty, powerful blows, which would be a property a warrior would look for in a sword designed to defeat mail or reinforced mail armour. Other great swords would be relatively more nimble due to a difference in their function, being a more "general purpose" sword. I am not saying one was wrong and one was right, just different tools for different purposes.

Also, I have admitted several times that I don't currently have access to quality replicas, and I'm aware of the limitations of lower-end replicas. At least MRL swords can be handled, even if they don't handle perfectly. I think some period swords may not have handled perfectly. I still know Windlasses fall short of period examples. Also, having taken apart several Windlass hilts, I am aware that their craftsmanship pales in comparison to period swords. When I mention the handling of the replicas I own, I've always try to do it in a comparative way, comparing one Windlass to another. I am not trying to compare Windlass swords to period examples or even higher quality replicas like Albions. I have read a lot on this web site, and I have absorbed a lot of knowledge. I think you can understand why I was leery about how people would view my comments, based on my lack of practical experience. I will be the first to admit that my practical experience is lacking, that's why I ask for input from other members with more practical experience. What I try to do is to bring the benefits of my obsessive "book learning" to the discussion.

Angus, I appreciate a wider scope, and that's what I'm asking for. Again, I understand the dangers of making generalities regarding medieval swords.

I hope you guys still feel I can make a worthwhile contribution to the discussion, even given my lack of practical knowledge. I'm trying to bring a thoughtful approach to the discussion, and cover many sides of the issue.

Again, I love to read about all observations. I'm one of those types that loves knowledge and learning (one of the reasons I home school my daughter).

Stay safe!

Angus and Patrick,

I appreciate input from both you guys, and I can see both sides of the issue. Some of this may be related to perceptions; I believe both of you may have talked about this stuff being rather subjective in nature.

I am not trying to say one sword type is good, or another is bad, I'm just trying to understand the variability of period examples. I have mentioned many times that I think there was a variability in the way swords even of the same type may handle, and both of you have mentioned this, too.

Patrick, you mentioned the fact that the fitness and training of medieval warriors was a factor in how they may have perceived period swords as compared to us moderns. I believe this is definitely an issue with some of the "heavier" and "more massive" great swords. Some were designed specifically to deliver weighty, powerful blows, which would be a property a warrior would look for in a sword designed to defeat mail or reinforced mail armour. Other great swords would be relatively more nimble due to a difference in their function, being a more "general purpose" sword. I am not saying one was wrong and one was right, just different tools for different purposes.

Also, I have admitted several times that I don't currently have access to quality replicas, and I'm aware of the limitations of lower-end replicas. At least MRL swords can be handled, even if they don't handle perfectly. I think some period swords may not have handled perfectly. I still know Windlasses fall short of period examples. Also, having taken apart several Windlass hilts, I am aware that their craftsmanship pales in comparison to period swords. When I mention the handling of the replicas I own, I've always try to do it in a comparative way, comparing one Windlass to another. I am not trying to compare Windlass swords to period examples or even higher quality replicas like Albions. I have read a lot on this web site, and I have absorbed a lot of knowledge. I think you can understand why I was leery about how people would view my comments, based on my lack of practical experience. I will be the first to admit that my practical experience is lacking, that's why I ask for input from other members with more practical experience. What I try to do is to bring the benefits of my obsessive "book learning" to the discussion.

Angus, I appreciate a wider scope, and that's what I'm asking for. Again, I understand the dangers of making generalities regarding medieval swords.

I hope you guys still feel I can make a worthwhile contribution to the discussion, even given my lack of practical knowledge. I'm trying to bring a thoughtful approach to the discussion, and cover many sides of the issue.

Again, I love to read about all observations. I'm one of those types that loves knowledge and learning (one of the reasons I home school my daughter).

Stay safe!

Hello again!

Patrick,

I just wanted to address this point as well as what I've already said in my previous post.

I definitely agree with you on this point, and I'm sorry if I wasn't clear about this. I might be fairly new to the forums, but I've been reading stuff here for a while. As I think you can gather, and you mentioned, I've been researching this stuff for a long time now, at least as far as I've been able. If your comment is addressed more at the "masses" than toward me, then ignore my ramblings.

Medieval sword smiths were craftsmen, like I've already said, and drew upon years and years of collective experience. A lot of modern companies that churn out lower-end products mass produce these things, and certain handling attributes do suffer as a consequence. Yes, the really "bad" (subjectively speaking, of course) period swords are undoubtedly in the minority, but we can't ever be 100% sure what was the accepted "norm". I doubt that "bad" swords were the norm at all, but I doubt that the "best" examples were the norm either. I think there may have been a bit of "you get what you pay for" back then as there is now. However, the swords still needed to function properly back then; warrior's staked their lives on their swords functioning properly. Today, lower end companies aren't under the same pressure to deliver absolutely functional products. That being said, plenty of people use MRL swords, and cut with MRL swords, and have had few problems. Many times the problems, if the sword blade is okay, can be fixed with a little do-it-yourself work. There are some issues with the sharp corners of the juncture of tang and the shoulders of the blade, and some users have had problems of breakages, but again some Windlasses are better than others. Obviously makers like Angus Trim, Albion, and Arms & Armor produce a much nicer product, but again at a much higher price (and a price that puts these items out of reach for some of us).

My point in all this is to gather information about the variability of the handling characteristics of certain period swords. There does seem to be some variability in period examples of the same type; different tools for different jobs, as we all keep saying. Some great swords were particularly "large" and "massive" (as in having a large mass - a lot of metal in the blade), and were designed for a specific purpose. I wanted to point out that some great swords could exhibit these features, while others might be a bit less "massive", and I think there are some examples that exhibit this variability. The more massive blades might feel heavy to some, especially to those who think all medieval swords must handle like a "tennis racket" or a "fishing rod". Some might even feel these swords are "boat anchors" (especially if the blade's mass is particularly large - like some especially broad examples), but it's all subjective. A strong and fit medieval knight might have desired such attributes in a blade that he would use on horseback against other well-armoured knights, but it might not be the best tool for a modern practitioner. Does any of this make sense, or am I just rambling down a long and winding road?

I also think that some of these great swords functioned as hand-and-a-half swords, perfectly usable in one hand or two, while some may have been meant more as true two-handed swords. There are some great swords shown in Records of the Medieval Sword (and that I recently posted on a thread about two-handed swords) that have such long hilts that they appear to almost be true two-handed swords. Many of these also possess larger blades, and might feel "heavier" (or more massive) as compared to smaller examples of great swords. Two-handed use would enable the warrior to strike with more power, using the strength of both arms. There were definite period references in the 12th-15th centuries of two-handed swords, and Oakeshott stated that these were often just oversized versions of the standard period types.

Again, I have enjoyed this discussion, even if at times we seem to have been at crossed purposes. I appreciate the "hands-on" input from those that have had a bit more practical experience than I have had.

Thanks!

Stay safe!

P.S. It was never my intention to stir up controversy, and I'm sorry if some of the things I said might have seemed like I was dredging up the old myth that sees medieval swords as "barely sharpened, horribly heavy bars of steel". It can be hard to discuss this sort of thing in this sort of venue, because a lot of this is subjective.

| Patrick Kelly wrote: |

|

Regardless of their feel they generally seem to have been designed with a specific goal in mind, not in the haphazard fashion that terms like "boat anchor", slow and ponderous", heavy", etc. would imply. There were bad swords made then just as now and I've seen a couple that I wouldn't have considered stellar examples but they seem to be in the surviving minority. |

Patrick,

I just wanted to address this point as well as what I've already said in my previous post.

I definitely agree with you on this point, and I'm sorry if I wasn't clear about this. I might be fairly new to the forums, but I've been reading stuff here for a while. As I think you can gather, and you mentioned, I've been researching this stuff for a long time now, at least as far as I've been able. If your comment is addressed more at the "masses" than toward me, then ignore my ramblings.

Medieval sword smiths were craftsmen, like I've already said, and drew upon years and years of collective experience. A lot of modern companies that churn out lower-end products mass produce these things, and certain handling attributes do suffer as a consequence. Yes, the really "bad" (subjectively speaking, of course) period swords are undoubtedly in the minority, but we can't ever be 100% sure what was the accepted "norm". I doubt that "bad" swords were the norm at all, but I doubt that the "best" examples were the norm either. I think there may have been a bit of "you get what you pay for" back then as there is now. However, the swords still needed to function properly back then; warrior's staked their lives on their swords functioning properly. Today, lower end companies aren't under the same pressure to deliver absolutely functional products. That being said, plenty of people use MRL swords, and cut with MRL swords, and have had few problems. Many times the problems, if the sword blade is okay, can be fixed with a little do-it-yourself work. There are some issues with the sharp corners of the juncture of tang and the shoulders of the blade, and some users have had problems of breakages, but again some Windlasses are better than others. Obviously makers like Angus Trim, Albion, and Arms & Armor produce a much nicer product, but again at a much higher price (and a price that puts these items out of reach for some of us).

My point in all this is to gather information about the variability of the handling characteristics of certain period swords. There does seem to be some variability in period examples of the same type; different tools for different jobs, as we all keep saying. Some great swords were particularly "large" and "massive" (as in having a large mass - a lot of metal in the blade), and were designed for a specific purpose. I wanted to point out that some great swords could exhibit these features, while others might be a bit less "massive", and I think there are some examples that exhibit this variability. The more massive blades might feel heavy to some, especially to those who think all medieval swords must handle like a "tennis racket" or a "fishing rod". Some might even feel these swords are "boat anchors" (especially if the blade's mass is particularly large - like some especially broad examples), but it's all subjective. A strong and fit medieval knight might have desired such attributes in a blade that he would use on horseback against other well-armoured knights, but it might not be the best tool for a modern practitioner. Does any of this make sense, or am I just rambling down a long and winding road?

I also think that some of these great swords functioned as hand-and-a-half swords, perfectly usable in one hand or two, while some may have been meant more as true two-handed swords. There are some great swords shown in Records of the Medieval Sword (and that I recently posted on a thread about two-handed swords) that have such long hilts that they appear to almost be true two-handed swords. Many of these also possess larger blades, and might feel "heavier" (or more massive) as compared to smaller examples of great swords. Two-handed use would enable the warrior to strike with more power, using the strength of both arms. There were definite period references in the 12th-15th centuries of two-handed swords, and Oakeshott stated that these were often just oversized versions of the standard period types.

Again, I have enjoyed this discussion, even if at times we seem to have been at crossed purposes. I appreciate the "hands-on" input from those that have had a bit more practical experience than I have had.

Thanks!

Stay safe!

P.S. It was never my intention to stir up controversy, and I'm sorry if some of the things I said might have seemed like I was dredging up the old myth that sees medieval swords as "barely sharpened, horribly heavy bars of steel". It can be hard to discuss this sort of thing in this sort of venue, because a lot of this is subjective.

Gus,

Again, all very valid points. Lately I've been a bit rushed with lifes other matters so I haven't had an excessive amount of time to really get into posting and reading here. That's what I get for trying to type a quick response. ;) I agree, we should be very careful about what we point to as the average or 'industry standard' for these things. However, the only thing I'd add to that is I think we do have enough surviving examples available for study that we can get a fairly good handle on the general properties desired in a given design. As for what was typical or not?.............................much more dicey to say.

Agreed about Craig and Peter. When they talk the rest of us need to sit down, shut up and learn something.

Richard,

I don't think you've caused any kind of controversy, just some interesting discussion. There's nothing wrong with that. As I've said before: the citations you've quoted from Oakeshott are very valuable for many others reading this thread. As I just told Gus in PM: some of us old timers tend to look at a lot of things as common knowledge. We've been communicating via cyberspace for close to a decade now and many things have been said so often that we take them for granted on a subconscious level. This is a bad habit to fall into and one I think I've been a bit guilty of in this thread. What I'm trying to say is that I apologize if it's seemed I was talking down to you with a "well duh..." attitude. That wasn't my intention. I suppose part of it is my own growing disenchantment with this electronic medium, it causes my patience to be a bit thin of late. Again, my apologies. Please, keep posting!

BTW, do you have Oakeshotts Sword in Hand? There's some interesting stuff there on this type of sword.

Again, all very valid points. Lately I've been a bit rushed with lifes other matters so I haven't had an excessive amount of time to really get into posting and reading here. That's what I get for trying to type a quick response. ;) I agree, we should be very careful about what we point to as the average or 'industry standard' for these things. However, the only thing I'd add to that is I think we do have enough surviving examples available for study that we can get a fairly good handle on the general properties desired in a given design. As for what was typical or not?.............................much more dicey to say.

Agreed about Craig and Peter. When they talk the rest of us need to sit down, shut up and learn something.

Richard,

I don't think you've caused any kind of controversy, just some interesting discussion. There's nothing wrong with that. As I've said before: the citations you've quoted from Oakeshott are very valuable for many others reading this thread. As I just told Gus in PM: some of us old timers tend to look at a lot of things as common knowledge. We've been communicating via cyberspace for close to a decade now and many things have been said so often that we take them for granted on a subconscious level. This is a bad habit to fall into and one I think I've been a bit guilty of in this thread. What I'm trying to say is that I apologize if it's seemed I was talking down to you with a "well duh..." attitude. That wasn't my intention. I suppose part of it is my own growing disenchantment with this electronic medium, it causes my patience to be a bit thin of late. Again, my apologies. Please, keep posting!

BTW, do you have Oakeshotts Sword in Hand? There's some interesting stuff there on this type of sword.

Hello all!

Patrick,

Thanks again for taking the time to respond to my comments. It's appreciated.

I'm getting to be a bit of an "old timer" when it comes to reading about and researching this stuff (at least since the mid 1980's, when I would scour my high school library for books about arms and armour after I became interested in role playing games), but I'm a relative "newbie" when it comes to posting. I have been trying to present a broad view for those that have not read some of these books over and over and over again (and again, and again, and again).

I can get rather impatient with the electronic medium as well, it's sometimes a difficult way to communicate.

Yes, I have Sword in Hand (I've actually cited from that a few times). I just got it this year as a birthday present. I think I posted the excerpt about the battle of Benevento from that work earlier in this post.

For those who don't have the book, let me say that it has a nice chapter about the great swords being talked about in this thread. It also has an interesting chapter about another type of large medieval sword, but one that has a small, one-handed size grip. I believe that Jean Thibodeau mentioned the sword found in Pontrirolo in North Italy. I was unaware of some of these massive one-handed swords before I acquired Sword in Hand, and I found the chapter about these "pre-great swords" illuminating.

I might have already posted the description of the Pontirolo sword (I can't remember everything I post), but here it is again:

Even though Oakeshott says the blade handles sweetly, it must handle somewhat differently (relatively speaking) than smaller-bladed swords with different weight distribution. It does sound like an early attempt at creating a "great sword", but with a smaller grip, just like Jean Thibodeau suggested in one of his previous posts. Oakeshott dates this large example of a type XIa to circa 1150. There are some long-hilted great swords from around the same period, but these big-bladed one-handed swords may be attempts to create a sword that functioned in a similar fashion to the more traditional longer-hilted great swords.

In the same chapter, Oakeshott also presented a few other examples of one-handed swords with particularly large blades. He used the term "heroic' to describe the dimensions of these swords. I think this is an evocative but appropriate term for these especially large swords.

Stay safe!

Patrick,

Thanks again for taking the time to respond to my comments. It's appreciated.

I'm getting to be a bit of an "old timer" when it comes to reading about and researching this stuff (at least since the mid 1980's, when I would scour my high school library for books about arms and armour after I became interested in role playing games), but I'm a relative "newbie" when it comes to posting. I have been trying to present a broad view for those that have not read some of these books over and over and over again (and again, and again, and again).

I can get rather impatient with the electronic medium as well, it's sometimes a difficult way to communicate.

Yes, I have Sword in Hand (I've actually cited from that a few times). I just got it this year as a birthday present. I think I posted the excerpt about the battle of Benevento from that work earlier in this post.

For those who don't have the book, let me say that it has a nice chapter about the great swords being talked about in this thread. It also has an interesting chapter about another type of large medieval sword, but one that has a small, one-handed size grip. I believe that Jean Thibodeau mentioned the sword found in Pontrirolo in North Italy. I was unaware of some of these massive one-handed swords before I acquired Sword in Hand, and I found the chapter about these "pre-great swords" illuminating.

I might have already posted the description of the Pontirolo sword (I can't remember everything I post), but here it is again:

| Ewart Oakeshott wrote: |

|

The sword's massive proportions put it into a class of its own...The overall length is 47.25 inches (120 cm): the blade is 40.5 inches (102.8 cm) long and 2.75 inches (7 cm) broad at the hilt; the cross is 8.5 inches wide and no less than 1 and 1/16 inches thick in the middle. The weight of the sword is just a whisker under 5 lb. A really massive weapon, but its grip is only 4.25 inches long, so in no way can it come into the same category of other types of Great Sword, or War Sword, whose grips are between 6 inches and 8 inches long. The pommel is not an elegantly finished pievce of work; in the lower part, beneath the deep patination of age, the smith's hammer-marks still show where he had a shot at forming it into a faceted shape, but it seems he soon gave up and quite roughly fashioned his massive cookie-like counterpoise to the great blade. It's point of balance is located just where the bladesmith's mark is, 31.125 inches (79 cm) up from the point. So, in spite of its weight, it handles sweetly. |

Even though Oakeshott says the blade handles sweetly, it must handle somewhat differently (relatively speaking) than smaller-bladed swords with different weight distribution. It does sound like an early attempt at creating a "great sword", but with a smaller grip, just like Jean Thibodeau suggested in one of his previous posts. Oakeshott dates this large example of a type XIa to circa 1150. There are some long-hilted great swords from around the same period, but these big-bladed one-handed swords may be attempts to create a sword that functioned in a similar fashion to the more traditional longer-hilted great swords.

In the same chapter, Oakeshott also presented a few other examples of one-handed swords with particularly large blades. He used the term "heroic' to describe the dimensions of these swords. I think this is an evocative but appropriate term for these especially large swords.

Stay safe!

Hello again!

Here's another example of those big one-handed swords that Oakeshott described rather subjectively, but, in my opinion poetically, as "heroic". These are slightly off-topic from great swords, but are definitely related to them, and could have an "evolutionary" link to their longer-hilted brethren.

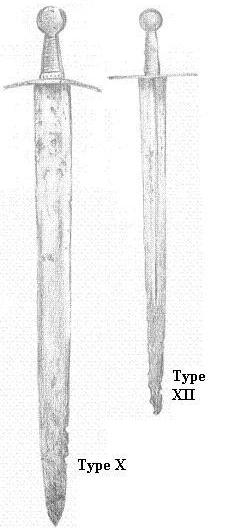

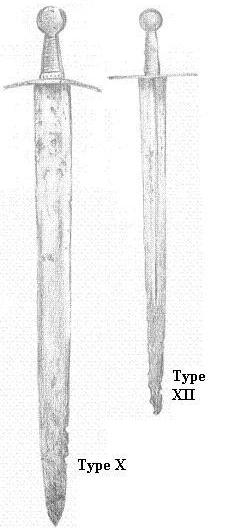

This one has been published in Records of the Medieval Sword ("Multiple Miscellaneous 26"), The Sword in the Age of Chivalry (Plate 2. B) and Ian Pierce's Swords of the Viking Age pg. 142, Musee de l'Armee, Paris J4). It's a sword that Oakeshott classified as a type X, but an extremely broad example of that type. This sword from the late eleventh or early twelfth century resides in the Musee de l'Armee, Paris.

There seems to be some confusion regarding the dimensions of this sword; Ian Peirce's dimensions of overall length of 85 cm and a blade length of 72 cm don't seem to match, when converted, Oakeshott's measurements of overall length of about 42 inches, and a blade length of 39 inches. Oakeshott stated that the blade is nearly 4 inches wide. Oakeshott does comment on the feel of the sword, saying it is not over-heavy (about 3 3/4 pounds) and handles "like a tennis racket or a fishing rod" (Oakeshott's own description). Peirce stated that the blade was extremely thin, as it would need to be to produce any degree of wieldability. It has an extremely broad (but shallow) fuller to match the extremely broad blade.

Oakeshott showed this sword alongside a more modest-sized type XII, the sword of Ramon Berengar III. These drawings are supposed to be to the same scale, but they might not be if Oakeshott's measurements are in error.

Does anyone have the correct measurements for this sword? Who was right; Oakeshott or Peirce? If this sword has a blade length of only 72 cm (28 inches by my calculations) then it would actually be shorter than what Oakeshott stated as the average for type X swords (average of 31 inches), but if it's blade measures 39 inches, then it would be larger than the average for the type. In any case, this sword has an extremely broad blade.

Anyway, here are Oakeshott's drawings from Records of the Medieval Sword (I switched the order of the pictures so the broad type X would be first, then the type XII):

Attachment: 17.3 KB

Attachment: 17.3 KB

Type X and Type XII from Records of the Medieval Sword

Here's another example of those big one-handed swords that Oakeshott described rather subjectively, but, in my opinion poetically, as "heroic". These are slightly off-topic from great swords, but are definitely related to them, and could have an "evolutionary" link to their longer-hilted brethren.

This one has been published in Records of the Medieval Sword ("Multiple Miscellaneous 26"), The Sword in the Age of Chivalry (Plate 2. B) and Ian Pierce's Swords of the Viking Age pg. 142, Musee de l'Armee, Paris J4). It's a sword that Oakeshott classified as a type X, but an extremely broad example of that type. This sword from the late eleventh or early twelfth century resides in the Musee de l'Armee, Paris.

There seems to be some confusion regarding the dimensions of this sword; Ian Peirce's dimensions of overall length of 85 cm and a blade length of 72 cm don't seem to match, when converted, Oakeshott's measurements of overall length of about 42 inches, and a blade length of 39 inches. Oakeshott stated that the blade is nearly 4 inches wide. Oakeshott does comment on the feel of the sword, saying it is not over-heavy (about 3 3/4 pounds) and handles "like a tennis racket or a fishing rod" (Oakeshott's own description). Peirce stated that the blade was extremely thin, as it would need to be to produce any degree of wieldability. It has an extremely broad (but shallow) fuller to match the extremely broad blade.

Oakeshott showed this sword alongside a more modest-sized type XII, the sword of Ramon Berengar III. These drawings are supposed to be to the same scale, but they might not be if Oakeshott's measurements are in error.

Does anyone have the correct measurements for this sword? Who was right; Oakeshott or Peirce? If this sword has a blade length of only 72 cm (28 inches by my calculations) then it would actually be shorter than what Oakeshott stated as the average for type X swords (average of 31 inches), but if it's blade measures 39 inches, then it would be larger than the average for the type. In any case, this sword has an extremely broad blade.

Anyway, here are Oakeshott's drawings from Records of the Medieval Sword (I switched the order of the pictures so the broad type X would be first, then the type XII):

Type X and Type XII from Records of the Medieval Sword

| Quote: |

| There seems to be some confusion regarding the dimensions of this sword; Ian Peirce's dimensions of overall length of 85 cm and a blade length of 72 cm don't seem to match, when converted, Oakeshott's measurements of overall length of about 42 inches, and a blade length of 39 inches. Oakeshott stated that the blade is nearly 4 inches wide. |

Here lies one of the faults in Oakeshotts work: many of his measurements were his best guess. Apparently, or so I've been told by those who knew him, he'd often examine a sword at an arms show or when viewing another collection and make a visual estimate as to length, or a guess as to weight according to how it felt in the hand. When Ian Peirce put his book together (in my opinion a superior one to Oakeshotts for what it is) I believe he actually took physical measurements of the specimens. So if I had to take one set of measurements as being accurate I'd have to go with Mr. Peirces.

I personally think the heavier swords are generally still quite fast in the initial attack, but often a bit slower in the recovery, meaning that striking tends to be just as quick (especially if you factor in a reach advantage) but followup displacements and counters sometimes are not. This however can be handled by the way you fight, using the strengths of a heavier sword , more authority at the bind, and (usually) the reach advantage which comes with it, in sparring I have used such weapons effectively by keeping within it's optimal (longer) range, and going to half-sword when the range is close. I had a couple of type XII and XXa sparring swords I used this way quite a bit.

By contrast, a lighter nimbler sword with a closer point of balance can be much quicker in reaction and from the bind, and tends to result in better closer-in fighting. I would agree with Patrick though that a 3-4 pound sword doesn't necessarily mean a clumsy weapon, or an overly simple fighting style. The ergonomics of the WMA techniques actually help you cope with the issue of weight quite well, by staying in the guards, using false edge cuts, twitches, miesterhau etc., you can fight quite a 'complex' fight with a formidable sword.

Incidentally, with a little practice you can make yourself practice and sparring weapons which match exactly to the weight and balance of real swords with commonly available household materials, which can give you a very similar 'feel' to the real thing. I'll be posting a thread on how to do this soon.

Jean

By contrast, a lighter nimbler sword with a closer point of balance can be much quicker in reaction and from the bind, and tends to result in better closer-in fighting. I would agree with Patrick though that a 3-4 pound sword doesn't necessarily mean a clumsy weapon, or an overly simple fighting style. The ergonomics of the WMA techniques actually help you cope with the issue of weight quite well, by staying in the guards, using false edge cuts, twitches, miesterhau etc., you can fight quite a 'complex' fight with a formidable sword.

Incidentally, with a little practice you can make yourself practice and sparring weapons which match exactly to the weight and balance of real swords with commonly available household materials, which can give you a very similar 'feel' to the real thing. I'll be posting a thread on how to do this soon.

Jean

Hello all!

Patrick,

Thanks! I was also leaning toward relying on Peirce's measurements instead of Oakeshott's. Oakeshott showed this same sword between two other type X's in plate 2 in The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. If the photos are roughly to scale, then the sword from the Musee de L'Armee would actually be of a fairly modest length. This would make it a bit less "heroic", but still very broad. I agree that Peirce presents a more "academic" approach to the subject.

I have tried to sit down and write out a summary of my thoughts regarding the particularly large and massive examples of the medieval war sword or great sword. Patrick, Angus, and others, tell me what you think about these statements regarding the larger great swords (obviously, this does not apply to all examples of the medieval great sword):

The particularly massive war swords or great swords used in the 12th through the 14th centuries appear to have been designed for a specific purpose: to strike hard, downward blows against an armoured opponent, almost in the fashion of how an axe is wielded. However, being swords, these weapons were capable of a greater variety of blows and movements than a simple axe. Still, the primary purpose of these large great swords seems to have been to deal great slashing blows from horseback. The greater length and mass of these swords meant they struck with authority, and could reach opponents at a greater distance, but also caused them to be less nimble than their more modestly-sized brethren. This comparative lack of agility was due in part to the greater recovery time demanded by the length and mass of these large great swords. Some of these great swords could have been used two-handed to aid in handling, but period art indicates that they were frequently used one-handed, especially by mounted warriors.

The fact that these great swords are slashing weapons is borne out by the fact that most have rounded, spatulate points. Thrusts would have been possible, but these swords weren't designed to deliver a powerful, well-aimed, thrust. The parallel-edges and balance points nearer the tip than many smaller swords seems to indicate that these great swords were designed primarily to deliver a hard, heavy-hitting, cutting blow. The longer hilts did help to counterbalance the long blades, and enabled the sword to be used two-handed if the need arose.

Other great swords possessed relatively less mass, or a different mass distribution. This seems to indicate that some were designed for a slightly different, more dynamic use, perhaps as more of a "general purpose" weapon. Period examples do seem to show a bit of variability in properties, indicating a variability in handling and usage. The larger examples of Oakeshott's types XII and XIII seem to have been referred to as "war swords" in many period sources, suggesting that they were designed specifically for the hurlyburly of the medieval battlefield. This isn't to say that they were horribly unwieldy, just that they were designed for an atmosphere where "power" was more important than "agility".

(A disclaimer: I apologize for the axe comparison, I'm not trying to say that these swords were axes, just that they could strike almost with the authority of an axe. Also, I don't know what else to compare the movement to. These swords were often, but not exclusively, used in a downward swing almost like an axe "chop".)

I hope this seemed to be a reasonable summation!

Stay safe!

| Patrick Kelly wrote: |

|

So if I had to take one set of measurements as being accurate I'd have to go with Mr. Peirces. |

Patrick,

Thanks! I was also leaning toward relying on Peirce's measurements instead of Oakeshott's. Oakeshott showed this same sword between two other type X's in plate 2 in The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. If the photos are roughly to scale, then the sword from the Musee de L'Armee would actually be of a fairly modest length. This would make it a bit less "heroic", but still very broad. I agree that Peirce presents a more "academic" approach to the subject.

I have tried to sit down and write out a summary of my thoughts regarding the particularly large and massive examples of the medieval war sword or great sword. Patrick, Angus, and others, tell me what you think about these statements regarding the larger great swords (obviously, this does not apply to all examples of the medieval great sword):

The particularly massive war swords or great swords used in the 12th through the 14th centuries appear to have been designed for a specific purpose: to strike hard, downward blows against an armoured opponent, almost in the fashion of how an axe is wielded. However, being swords, these weapons were capable of a greater variety of blows and movements than a simple axe. Still, the primary purpose of these large great swords seems to have been to deal great slashing blows from horseback. The greater length and mass of these swords meant they struck with authority, and could reach opponents at a greater distance, but also caused them to be less nimble than their more modestly-sized brethren. This comparative lack of agility was due in part to the greater recovery time demanded by the length and mass of these large great swords. Some of these great swords could have been used two-handed to aid in handling, but period art indicates that they were frequently used one-handed, especially by mounted warriors.

The fact that these great swords are slashing weapons is borne out by the fact that most have rounded, spatulate points. Thrusts would have been possible, but these swords weren't designed to deliver a powerful, well-aimed, thrust. The parallel-edges and balance points nearer the tip than many smaller swords seems to indicate that these great swords were designed primarily to deliver a hard, heavy-hitting, cutting blow. The longer hilts did help to counterbalance the long blades, and enabled the sword to be used two-handed if the need arose.

Other great swords possessed relatively less mass, or a different mass distribution. This seems to indicate that some were designed for a slightly different, more dynamic use, perhaps as more of a "general purpose" weapon. Period examples do seem to show a bit of variability in properties, indicating a variability in handling and usage. The larger examples of Oakeshott's types XII and XIII seem to have been referred to as "war swords" in many period sources, suggesting that they were designed specifically for the hurlyburly of the medieval battlefield. This isn't to say that they were horribly unwieldy, just that they were designed for an atmosphere where "power" was more important than "agility".

(A disclaimer: I apologize for the axe comparison, I'm not trying to say that these swords were axes, just that they could strike almost with the authority of an axe. Also, I don't know what else to compare the movement to. These swords were often, but not exclusively, used in a downward swing almost like an axe "chop".)

I hope this seemed to be a reasonable summation!

Stay safe!

Hi Richard,

Please forgive me for butting in, but while this sounds quite possibly accurate for how such a weapon could be used from horseback in circumstances where a single ride-by attack might be meted out by a charging horseman, I'm not sure this was the intended primary function of the weapon, I believe there is more to the whole picture. We know the primary weapon of most mounted warrior in this period was a lance or a thrusting spear. If their sword were intended for ride-by cutting attacks I would submit that they would have resorted to the use of sabers. If they needed specialized armor-piercing weapons, hammers, axes, or military picks (which were also known in this era) would have been preferable.

We also know well that knights and heavy cavalry soldiers or warriors of this period often fought on foot. This is where I would argue that the first greatswords proved their worth (as ever larger swords so often did in later places in later eras, whether Scottish or Irish 'Claymore' type weapons, or the so called "Dopplehanders" of the landsknechts)

On foot, the advantage of a longer hand-and-a-half-sword, even if only a matter of 6 inches or so, should not be underestimated. I've personally always been suspicious of the common assertion that the two-handed swords of the greatsword / longsword family were intended for use simply to cut through armor. Modern tests have shown that riveted Maille isn't very easy to cut through with most swords, for one thing. We can also speculate with some reasonable degree of certainty that complete cap-a-pied armor panoplies were fairly rare even in the 13th century, so cutting through armor may not have often been a better solution than cutting around armor (as the French seem to have done in the historical example cited earlier in this thread).

For another, this theory simply doesn't take into consideration the dynamics of the fight. Fighting (on foot) with a shorter weapon means generally fighting with a shield. Having participated in many hundreds of sparring bouts between longsword fighters and sword and shield fighters, I know a bit of the advantages that each has. The latter is more defensive, particulalry for less experienced fighters, but the former has much more of an ability to control the pace of the fight. Reach is incredibly important in hand to hand weapon combat. Thats why you see so many logn hafted weapons persisting since the dawn of time.

With all due respect, this sounds like it is spoken by someone with little experience of WMA. All other things being equal, in a situation wherre a man is armed with a 'typical' (if such an idea can be allowed for the sake of argument) Oakeshott XIIIa facing with an opponent armed with an Oakeshotte XIV, with or without a shield, the man with the XIIIa has a huge reach advantage which actually translates as a speed advantage even if his sword is a pound or more heavier. From my experience, if the two fighters were advancing toward each other the guy with the 'heavier and clumsier' XIIIa would get the first strike in nine times out of ten.

Think about it this way, if you have a 4' hand-and-a-half sword, and your opponent has a two foot baselard, your baselard may be theoretically faster due to being half the weight, but effectively the 4 foot sword is going to be much faster. Try this out with a couple of sticks with a friend, see who can touch the other first.

Jean

| Richard Fay wrote: |

| Hello all!

Still, the primary purpose of these large great swords seems to have been to deal great slashing blows from horseback. The greater length and mass of these swords meant they struck with authority, and could reach opponents at a greater distance, but also caused them to be less nimble than their more modestly-sized brethren. This comparative lack of agility was due in part to the greater recovery time demanded by the length and mass of these large great swords. Some of these great swords could have been used two-handed to aid in handling, but period art indicates that they were frequently used one-handed, especially by mounted warriors. |

Please forgive me for butting in, but while this sounds quite possibly accurate for how such a weapon could be used from horseback in circumstances where a single ride-by attack might be meted out by a charging horseman, I'm not sure this was the intended primary function of the weapon, I believe there is more to the whole picture. We know the primary weapon of most mounted warrior in this period was a lance or a thrusting spear. If their sword were intended for ride-by cutting attacks I would submit that they would have resorted to the use of sabers. If they needed specialized armor-piercing weapons, hammers, axes, or military picks (which were also known in this era) would have been preferable.

We also know well that knights and heavy cavalry soldiers or warriors of this period often fought on foot. This is where I would argue that the first greatswords proved their worth (as ever larger swords so often did in later places in later eras, whether Scottish or Irish 'Claymore' type weapons, or the so called "Dopplehanders" of the landsknechts)

On foot, the advantage of a longer hand-and-a-half-sword, even if only a matter of 6 inches or so, should not be underestimated. I've personally always been suspicious of the common assertion that the two-handed swords of the greatsword / longsword family were intended for use simply to cut through armor. Modern tests have shown that riveted Maille isn't very easy to cut through with most swords, for one thing. We can also speculate with some reasonable degree of certainty that complete cap-a-pied armor panoplies were fairly rare even in the 13th century, so cutting through armor may not have often been a better solution than cutting around armor (as the French seem to have done in the historical example cited earlier in this thread).

For another, this theory simply doesn't take into consideration the dynamics of the fight. Fighting (on foot) with a shorter weapon means generally fighting with a shield. Having participated in many hundreds of sparring bouts between longsword fighters and sword and shield fighters, I know a bit of the advantages that each has. The latter is more defensive, particulalry for less experienced fighters, but the former has much more of an ability to control the pace of the fight. Reach is incredibly important in hand to hand weapon combat. Thats why you see so many logn hafted weapons persisting since the dawn of time.

| Quote: |

|

This isn't to say that they were horribly unwieldy, just that they were designed for an atmosphere where "power" was more important than "agility". |

With all due respect, this sounds like it is spoken by someone with little experience of WMA. All other things being equal, in a situation wherre a man is armed with a 'typical' (if such an idea can be allowed for the sake of argument) Oakeshott XIIIa facing with an opponent armed with an Oakeshotte XIV, with or without a shield, the man with the XIIIa has a huge reach advantage which actually translates as a speed advantage even if his sword is a pound or more heavier. From my experience, if the two fighters were advancing toward each other the guy with the 'heavier and clumsier' XIIIa would get the first strike in nine times out of ten.

Think about it this way, if you have a 4' hand-and-a-half sword, and your opponent has a two foot baselard, your baselard may be theoretically faster due to being half the weight, but effectively the 4 foot sword is going to be much faster. Try this out with a couple of sticks with a friend, see who can touch the other first.

Jean

Hi Richard

I think maybe you're trying to get to detailed a picture of what these swords were used for. I personally don't think the heavier ones would be that handy on horseback {though that's an opinion}.....

I don't think you're going to have much success cutting through helmets....

I don't think you're going to have much success cutting thru maille backed by good padding.....

Etc.......

Things of the medieval world are fairly unclear today. For years, certain truths have been repeated, like only 10% of medieval combatants were armored to a large degree...... But do we really know that?

I'd be cautious about trying to close the door on these. Its obvious that some were designed with durability being prime, its also obvious that some had cutting ability more important {think edge geometry, weight, and tang construction}.......

I think Jean has a point, but even so, I'd suggest an open mind, and don't draw iron clad conclusions.........

I think maybe you're trying to get to detailed a picture of what these swords were used for. I personally don't think the heavier ones would be that handy on horseback {though that's an opinion}.....

I don't think you're going to have much success cutting through helmets....

I don't think you're going to have much success cutting thru maille backed by good padding.....

Etc.......

Things of the medieval world are fairly unclear today. For years, certain truths have been repeated, like only 10% of medieval combatants were armored to a large degree...... But do we really know that?

I'd be cautious about trying to close the door on these. Its obvious that some were designed with durability being prime, its also obvious that some had cutting ability more important {think edge geometry, weight, and tang construction}.......

I think Jean has a point, but even so, I'd suggest an open mind, and don't draw iron clad conclusions.........

Richard,

I think you're trying to define this type of sword within a set of parameters that are too narrow.

I was working out with my Albion Baron this morning in the backyard. I haven't done this with that particular sword in some time and was newly pleased with the swords dynamic handling. I found it to be easily transitioned between many of the guards and attacks of later schools of longsword use. It wasn't designed with these techniques specifically in mind but it does illustrate the point that this type of sword is capable of diverse usage. Far more so than just heavy downward blows. Part of this may be due to the fact that I've been spending 1-1.5 hours in the gym, 5-6 days a week since the beginning of the year but I'm not nearly as tough as our ancestors who used these things. The problem I have with this statement is it seems to put the sword into an operational box that is far too small. I don't agree with view that this type of sword was primarily meant for use on horseback. I think it would be effective when used in that manner but I don't see that as its primary purpose. The medieval knight could and often did fight on foot and I've always seen these swords as being at their best when used in that fashion.

I do feel these swords were primarily cutting dedicated designs, as were most other types of the day. However, as with some of their single-handed brethren there does seem to be a clear concern over developing a sword that was more thrusting capable. When using Oakeshotts typology we can see a clear difference between a Type XIIa and a XIIIa, etc.

I think you're trying to define this type of sword within a set of parameters that are too narrow.

| Quote: |

| The particularly massive war swords or great swords used in the 12th through the 14th centuries appear to have been designed for a specific purpose: to strike hard, downward blows against an armoured opponent, almost in the fashion of how an axe is wielded. However, being swords, these weapons were capable of a greater variety of blows and movements than a simple axe. Still, the primary purpose of these large great swords seems to have been to deal great slashing blows from horseback. |

I was working out with my Albion Baron this morning in the backyard. I haven't done this with that particular sword in some time and was newly pleased with the swords dynamic handling. I found it to be easily transitioned between many of the guards and attacks of later schools of longsword use. It wasn't designed with these techniques specifically in mind but it does illustrate the point that this type of sword is capable of diverse usage. Far more so than just heavy downward blows. Part of this may be due to the fact that I've been spending 1-1.5 hours in the gym, 5-6 days a week since the beginning of the year but I'm not nearly as tough as our ancestors who used these things. The problem I have with this statement is it seems to put the sword into an operational box that is far too small. I don't agree with view that this type of sword was primarily meant for use on horseback. I think it would be effective when used in that manner but I don't see that as its primary purpose. The medieval knight could and often did fight on foot and I've always seen these swords as being at their best when used in that fashion.

I do feel these swords were primarily cutting dedicated designs, as were most other types of the day. However, as with some of their single-handed brethren there does seem to be a clear concern over developing a sword that was more thrusting capable. When using Oakeshotts typology we can see a clear difference between a Type XIIa and a XIIIa, etc.

Hello all!

Okay, I've tried to present a thoughtful discussion about the issue of the use of great swords based on my research of history. I knew sooner or later my lack of "practical experience" would crop up. I would argue that certain swords might not be the best when used in a "modern" Western Martial Arts style, but now I know I am just banging my head against the wall. I have presented examples of descriptions of an actual period battle, and have repeatedly referred to period art. I am trying to draw conclusions of how these things were typically used in period, not how someone uses them today.

I believe the period name for these swords, war swords, says something about their intended use! That these were used by knights in a time (at least in the early years of the use of these swords) in which knights typically fought from horseback (but not exclusively) implies strongly that they were used from horseback. The fact that these were knightly weapons is again backed up by period art and textual references. I'm not saying that they were the best weapon to use from horseback, but history seems to indicate that they were used in this fashion!

How did the German mercenaries of Manfred of Sicily defeat the French knights (implying armoured mounted warriors, especially for the date of 1266) at the battle of Benevento, at least until the French utilized the specific property of their own smaller, more pointed swords to exploit gaps in the German armour? This historical battle, well-documented in period sources (although I will admit I'm taking my description from Oakeshott) describes the way in which the Germans used their big swords, and it is not in the least unclear. It also implies that the great swords of the Germans were effective against the French. If not, why were the French in such a predicament?

(Oakeshott's description of the German men-at-arms in the service of Manfred of Sicily called them "large, heavy, well-trained, disciplined warriors on big horses, armed with long war swords...")

I also thought I said "seems" and other less-than-absolute words enough to show that I was only implying a possible conclusion. There is always going to be variability and differences.

I have said much of this previously, and I am now tired of repeating myself.

I have had many suggestions flung my way, and some very useful and helpful, now I will fling one out for everyone else (and to those that already do this, ignore it): Read more books! Examine period art, read period accounts.

I feel that, no matter what I say, it will now get shot down. I feel this has turned from a discussion into an argument, and I think I've said all I can (or wish to) say.

I'm withdrawing myself from this discussion thread. I'm ready to move on to less volatile issues.

Thanks to everyone for their input.

Stay safe!

Okay, I've tried to present a thoughtful discussion about the issue of the use of great swords based on my research of history. I knew sooner or later my lack of "practical experience" would crop up. I would argue that certain swords might not be the best when used in a "modern" Western Martial Arts style, but now I know I am just banging my head against the wall. I have presented examples of descriptions of an actual period battle, and have repeatedly referred to period art. I am trying to draw conclusions of how these things were typically used in period, not how someone uses them today.

I believe the period name for these swords, war swords, says something about their intended use! That these were used by knights in a time (at least in the early years of the use of these swords) in which knights typically fought from horseback (but not exclusively) implies strongly that they were used from horseback. The fact that these were knightly weapons is again backed up by period art and textual references. I'm not saying that they were the best weapon to use from horseback, but history seems to indicate that they were used in this fashion!

How did the German mercenaries of Manfred of Sicily defeat the French knights (implying armoured mounted warriors, especially for the date of 1266) at the battle of Benevento, at least until the French utilized the specific property of their own smaller, more pointed swords to exploit gaps in the German armour? This historical battle, well-documented in period sources (although I will admit I'm taking my description from Oakeshott) describes the way in which the Germans used their big swords, and it is not in the least unclear. It also implies that the great swords of the Germans were effective against the French. If not, why were the French in such a predicament?