I've split this off the "cuir boulli quandary" thread, since I think it deserves a discussion of its own.

| Dan Howard wrote: |

|

Current thinking is that "studded leather" is a misinterpretation of brigandine illustrations. Studded armour did not exist historically. Practical experimentation suports this. Adding metal studs to leather or quilted cloth provides virtually no additional protection against any of the weapons faced on a medieval battlefield. |

Dan,

I must disagree with your position regarding studded armour. There are a few examples of Chinese cloth armour that possess studs but no underlying plates. One of about 1840 is shown in a photo in George Cameron Stone's massive glossary of arms and armour. Granted, it's probably more ceremonial than practical, being armour of the officers of the Imperial Guard. Another is shown in Stephen Turnbull's An Historical Guide to Arms and Armour. This one from the Kienlung Period of 1736-95 has a few plates on the shoulders and chest, but the majority of the protection is provided by quilted fabric peppered with round studs.

Here are the actual descriptions of the Chinese studded cloth "armours" straight from my sources:

| George Cameron Stone wrote: |

|

Chinese armour of officers of the Imperial Palace Guard. About 1840. Gold brocade embroidered in colours and edged with black velvet. Gilt rivet heads but no plates. The shoulder pieces are gilded dragons. The helmet is plain steel with gilded ornaments. |

(From A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armour in all Countries and in all Times.)

I agree that the one in Stone seems to be purely a ceremonial, decorative garment. It is shown next to a more proper Chinese "brigandine", another Imperial Palace Guard Officer's armour with small plates held beneath the fabric by rivets. The next example, however, may serve some protective function.

| Stephen Turnbull wrote: |

|

Quilted Chinese armour of the Kienlung Period, 1736-95. Here quilted fabric is the main form of protection; plates appear only on the shoulder and in the helmet. The helmet itself has a quilted lining and the metal parts are decorated with dragons soaring in clouds (The Field Museum, Chicago). |

(From An Historical Guide to Arms & Armor)

Note that this second garment is quilted, which would offer a light protection like an ordinary gambeson. I'm not saying their is a direct evolutionary link between the Chinese "studded quilted armours" (if there was one, I assume there were others) and the garments on the early 14th century English brasses, but I'm utilizing the same notion that anthropologists use when they study modern "Stone Age" peoples to get an idea about how prehistoric "Stone Age" peoples lived.

I agree that this "studded quilted armour" must provide minimal protection at best, and many claims of medieval studded armour are misinterpretations of brigandine, but these studded cloth Chinese armours bear a striking resemblance to some of the torso protection worn over the hauberk on some of the early 14th century English brasses.

Some of the older authors (like Charles Henry Ashdown and Charles ffoulkes) used to call these garments of the "cyclas period" "gambesons" or "upper pourpoints". They used to think that these represented padded garments, not early coats-of-plates, but recent authors have rejected this notion. After taking a close look at quality illustrations and reproductions of some of these brasses (like the pictures in Henry Trivick's The Picture Book of Brasses in Gilt and the drawings in Charles Henry Ashdown's European Arms and Armor), I'm not sure the idea should be so easily discarded. (By the way, the Trivick book took almost all the images "off the top of the brass" originals and then reproduced these in positive "gilt and black". And, yes, this book shows all three brasses I refer to.)

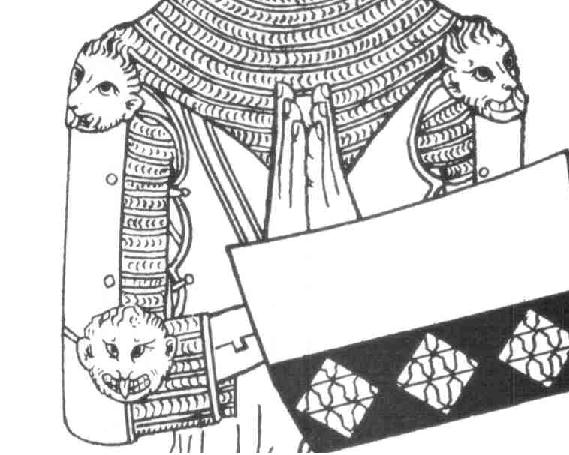

Take a close look at the brasses of Sir John D'Aubernoun the Younger of 1327 or Sir John De Creke of 1325. Both wear a studded garment beneath the "cyclas" and over the hauberk. Both garments show lines similar to the quilting lines on the gambesons or aketons underneath the mail. These possible (probable?) "stitching lines" are carved as double-lines, very similar to the way the stitching is shown on the gambesons or aketons depicted on even earlier brasses, like those of Sir William fitz Ralph and Sir William de Setvans. The lines can be seen at the armpit on each, and in each case it curves to follow the curve of the body. Also, there appear to be no studs in the armpit area. The hem line on these garments also seems awfully low for a coat-of-plates. Furthermore, the D'Aubernoun brass shows rivets or studs along the lines as well as down the middle of the rows, a strange configuration if the "studs' were holding plates beneath the fabric. Finally, the brass of Sir John de Northwood may show the garment worn beneath the mail, although the lower half is a palimpset and may be an inaccurate restoration.

Later brasses such as the lost brass of Sir Miles de Stapleton, from an impression in the British Museum, show armour that more clearly represents a coat-of-plates or early brigandine. There are no "stitching" lines, and the rivets are lined up in nice neat rows.

Apparently, English armour of the early 14th century was known as being old-fashioned. In Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: the English Experience by Michael Prestwich, the author states that Jean le Bel had commented on how old-fashioned English armour was compared to that on the continent. Gambesons were worn over mail occasionally in the 13th century; a few soldiers in the Maciejowski Bible are so equipped. Perhaps the D'Abernoun the Younger and the De Creke brasses show a late survival of this sort of thing. Even if these garments are a sort of gambeson rather than a coat-of-plates, the "studs" may be more decorative than protective. Again remember that these brasses are from a time of experimentation in armour; even if they are "studded cloth", the concept didn't last long!

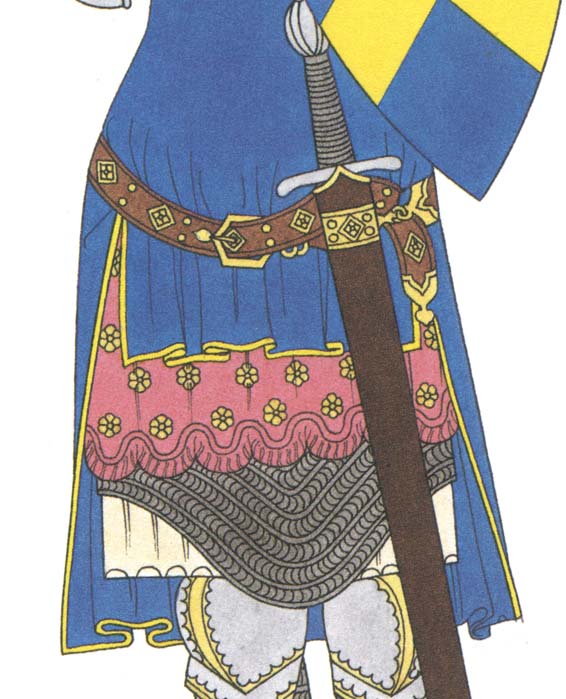

Now "stud and splint" or just "splinted" armour, armour made from leather (or perhaps cloth) reinforced with strips of metal, sometimes accompanied with "studs" or "disks" was widely used in Germany and sometimes elsewhere. Look at the effigy of Kaiser Gunther of Schwarzburg, for instance. The arms and legs are protected with mail supplemented with armour of leather (cloth?) reinforced with strips and disks. It was perhaps a "cheap" or "light" alternative to full plate. Or, could it be the Germans just thought it looked "mean"? (Line drawings of many of these effigies can be seen in J.H. Hefner-Alteneck's Medieval Arms and Armor: a Pictorial Archive. I've seen photos of some in other sources that closely match the drawings, so I have no reason to believe that the drawings are inaccurate.)

Of course, I agree with you that the typical "studded leather" armour so popular in role playing games was never used, as far as we know, as a torso defence!

I wish I could post the images of the brasses or the Chinese armours; perhaps someone else can!

I hope you found this of interest!

Stay safe!