Hello all!

Since I began a thread talking about "studded armour", and I mentioned the "studded and splinted" armour as seen on various German effigies of the 14th century, I thought I might make a list of what I've found to open another thread specifically about "studded and splinted armour". So, here are some examples of splinted or studded and splinted armour I've found in my library. Some may be seen as a form of brigandine, but not most. Some contain "studs" as well as "splints", but many more contain just "splints". Some are shown as drawings in the various sources, but most are photos of the actual effigies. I hope this reference list is of interest!

Armed warrior of 1345-1350 from a sculpture depicting the Guardians of the Holy Sepulchre, Breisgau Cathedral. The warrior with splinted armour wears what may be a "formed" or "hardened" leather vambrace. It has thin, widely-spaced splints. No studs. (Seen in Paul Martin's Arms and Armour and David Nicolle's Campaign 71: Crecy 1346: Triumph of the Longbow.)

Mid 14th century warrior carved on a wooden Levitic Pew end in Verden Cathedral. The warrior wears vambraces and rerebraces of narrow splints on a foundation material, possible leather. No studs. (Seen in Nicolle's Crecy 1346 and Christopher Gravett's German Medieval Armies 1300-1500.)

The effigy of Gotfried von Berheim, 1335, in Munstereifel Church. The knight wears vambraces consisting of fairly wide splints attached to a leather or cloth backing. (Seen in Gravett's German Medieval Armies 1300-1500.)

The effigy of Burkhard von Steinberg, 1397, in the Roemer-Museum. The knight wears vambraces of studded and splinted construction, narrow strips alternating with vertical rows of studs or rivets. (Seen in Gravett's German Medieval Armies 1300-1500 and J.H. Hefner-Alteneck's Medieval Arms and Armor: a Pictorial Archive.)

Effigy of Conrad von Seinheim, 1369, in the Church of St. John, Schweinfurt. The effigy shows splinted armour on the limbs. No studs. (Seen in Nicolle's Campaign 65: Nicopolis 1396: the Last Crusade.)

A miniature from De Bello Pharsalico of 1373 shows one soldier with "studded" cuisses and greaves (brigandine?). (Seen in Nicolle's Nicopolis 1396.)

Effigy of the Margrave Rudolph IV of Baden-Durlach, 1346, in Lichtental, Germany. This effigy shows fairly narrow, single splints without a backing material, worn over the sleeves of the haubergeon. (Seen in Stephen Turnbull's Campaign 122: Tannenberg 1410: Disaster for the Teutonic Knights.)

Effigy of Dieter von Hohenberg, 1381, Burg Homberg, Bavaria. The knight wears splint rerebraces and vambraces, and greaves constructed of formed splints held together with straps. (Seen in Vesey Norman's Arms and Armor.)

Effigy of Otto von Orlamunde, 1340, in the Convent Church at Himmelkron, Bavaria. The knight wears vambraces of fairly wide splints on a backing material. (Seen in Norman and Hefner-Alteneck.)

Effigy in Tewkesbury. The knight wears cuisses constructed of close-set, rivetted splints. (Seen in Charles Henry Ashdown's European Arms and Armor.)

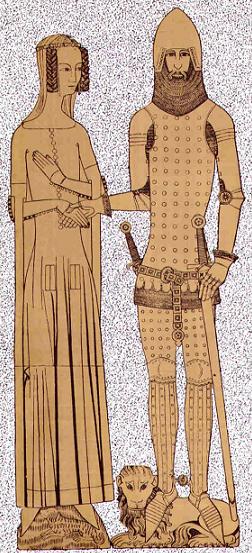

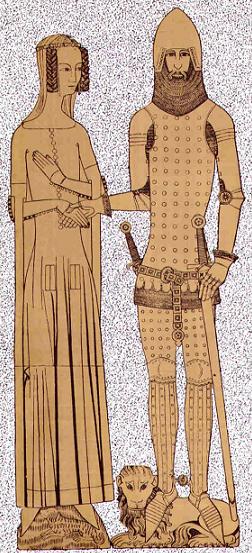

Brass (lost, but an impression remains) of Sir Miles de Stapleton, once in Ingham Church, Norfolk. The brass shows probable brigandine cuisses, coat-of-plates or brigandine coat, and splinted greaves. The narrow strips are held onto the backing material by visible rivets. (Seen in Ashdown, Henry Trivick's The Picture Book of Brasses in Gilt and David Edge and John Miles Paddock's Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight.)

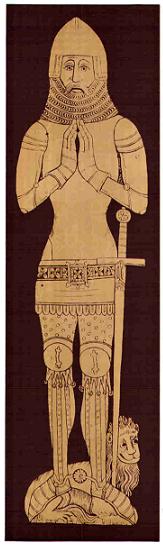

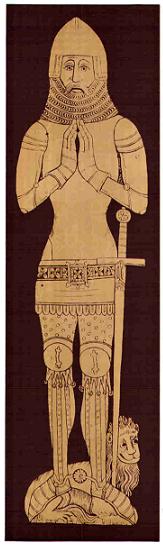

Sir Thomas Cheyne, 1368. The knight wears greaves of rivetted splints, very similar to that worn by Stapleton. (Seen in Ashdown.)

Effigy of Gunther von Schwarzburg, 1349, Frankfurt am Main Cathedral. The knight wears studded and splinted limb protection of long, narrow strips alternating with rows of studs, rivets, or disks attached to a backing material. (Seen in Martin and Hefner-Alteneck.)

Effigy of Walther Bopfinger, 1359, at Bopfinger (Wurttemberg). The knight wears vambraces and gauntlets cuffs constructed of fairly wide splints attached to a backing material. No studs or rivets. (Seen in Martin and Hefner-Alteneck.)

Effigy of Heinrich von Seinsheim, 1360, Wurtburg Cathedral. The knight's arms and lower legs bear armour of splints on a backing material. No studs or rivets. (Seen in Martin and Alteneck.)

Effigy of Gottfried, Count of Arensberg, 1370. The forearms are defended by rivetted splints attached to a backing material. The upper arms and shins bear narrow plates secured over mail. (Seen in Hefner-Alteneck.)

Effigy of Huglin of Shoeneck, 1374. The greaves are constructed of splints attached to a backing material. No studs. (Seen in Alteneck.)

Effigy of Sir William de Kerdiston, c. 1361, in Reepham Church. The knight wears cuisses constructed of ridged splints attached to a backing material. No studs. (A drawing by Stothard.) (Seen in Gravett's English Medieval Knight 1300-1400.)

Tomb slab of Lorenzo Acciaili, 1353, in Florence. The knight, in elaborately decorated armour, wears rivetted splint vambraces, and splint and possibly rivetted cuisses. (Seen in Ewart Oakeshott's Sword in Hand.)

There are a few more Italian and German examples in David Nicolle's Arms and Armour: the Crusading Era 1050-1350: Western Europe and the Crusader States, but the drawings lack detail, so I won't include them here.

Does anyone have any other examples of this type of armour that they wish to share on this thread? And, if so, can you post some pictures?

I hope this list was a helpful resource. it does seem to show that 14th century armour, especially in Germany, could vary a great deal from knight to knight. More materials than just iron and steel alone were used during the age of armour experimentation!

Stay safe!

The leg protection is usually called "gamboised cuisses". They are textile leg protection stuffed and quilted. They can't be classified as "studded armour" because the only time "studs" were used was when metal was added for reinforcing - either inside or outside (sometimes both). When reinforced with metal inside, only the rivets were visible. The image of Acciaioli on p123 of Oakeshott's "Sword in Hand" is an example of metal reinforcing both inside and outside.

Hello all!

Dan,

I must disagree again with your assessment. I am fully aware that knights sometimes wore "gamboised cuisses", padded tubular defences for the thighs. I've even made a couple pairs myself; nothing that would pass in a living history group, since I used "bargain fabric" from the local Wal-Mart, but just to get the general idea of the form of these defences. I could list several examples of this type of defence shown on effigies and other works of art, but it would detract from this thread. I believe the brasses of William de Setvans and Sir William fitz Ralph are good examples. They definitely show a padded garment worn above the poleyn. It only shows slightly from beneath the gambeson (or aketon), but it's there.

What I am describing is definitely made from strips of some material, most probably metal, attached to a backing material. Several German effigies, and a few English and Italian, show this sort of defence. It is usually worn as a supplement to the mail sleeves and chausses. If you look carefully at some of the photos of the sculptures (the figure on the wooden Levitic Pew is a good example), you can clearly see that the splints stand above the backing material. There is no reason to believe that these were constructed with splints alternating on the outside and the inside; this seems an awkward configuration at best. I wish I could post photos of what I am talking about, but unfortunately I have the type of scanner that only takes single pages, and I don't want to destroy my various books. I would suggest that you talk a look at some of the photos yourself; I tried to list the books I used for the sources of my information.

I also must disagree with your assessment that the studs or rivets always hold plates beneath the backing material. The ones that show splints (and these are indeed splints, like I already said, they stand proud from the backing material in the better sculptures and effigies) and studs or disks are in the minority, but they do exist. The effigy of Gunther von Schwarzberg is a good example. If you have access to the book, take a look at the colour plate by Angus McBride in Christopher Gravett's Osprey book German Medieval Armies 1300-1500 that shows von Schwarzberg. It gives a good idea of what the greaves may have actually looked like. I know Osprey books are sometimes suspect; but that particular reconstruction is taken directly off the effigy. The greaves, rerebraces, and vambraces definitely consist of vertical splints alternating with vertical rows of studs or disks. There is no reason to believe that the studs or disks are attached to larger plates underneath; many of the German effigies lack any sign of material other than the backing material between the splints. There is also no reason to believe that the Acciaioli effigy has any plates beneath the backing material. It appears that this idea is similar to the early coat of plates or reinforced surcoat where the plates did not overlap. Perhaps they felt some form of reinforcement was better than none!

I am not alone in my belief that these effigies show "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour; I am just following what others that have studied the actual effigies, like David Nicolle, have said about the armours' apparent construction. Nicolle and Gravett, as well as Hefner-alteneck and Ashdown (although the accuracy of the interpretations by these earlier authors may be a bit suspect) have all interpreted the armour the same way.

Perhaps it really just the name were disagreeing about; what if I called these armours on the German effigies merely "splinted armour"?

Oh, by the way, Rene d'Anjou's treatise on tournaments showed leather (cuir bouilli) full vambraces that were reinforced with cords. I've heard of a similar configuration, but reinforced with wooden splints. Perhaps this is a late survival for the tournament of the same sort of idea that I am describing.

I hope this clarifies my position regarding these 14th century German effigies. Again, maybe if you could see what I was talking about, it might help to clarify the matter.

Oh, and in the case of the 14th century German effigies, I'm not saying that it was ever merely just studded. I am saying that you occasionally would see a "studded and splinted" configuration alongside the more usual "splinted".

A final note; keep in mind that these "splinted" armours probably had formed or hardened leather as a backing material. The metal bits were just extra reinforcements. The warrior with the probable leather vambrace with splints depicted in Breisgau Cathedral is a good example of how little metal may actually have gone into the construction of the armour pieces. The splints are there, but so narrow and widely spaced that they couldn't have offered a great deal of added protection.

I hope this made sense!

Stay safe!

| Dan Howard wrote: |

|

The leg protection is usually called "gamboised cuisses". They are textile leg protection stuffed and quilted. They can't be classified as "studded armour" because the only time "studs" were used was when metal was added for reinforcing - either inside or outside (sometimes both). When reinforced with metal inside, only the rivets were visible. The image of Acciaioli on p123 of Oakeshott's "Sword in Hand" is an example of metal reinforcing both inside and outside. |

Dan,

I must disagree again with your assessment. I am fully aware that knights sometimes wore "gamboised cuisses", padded tubular defences for the thighs. I've even made a couple pairs myself; nothing that would pass in a living history group, since I used "bargain fabric" from the local Wal-Mart, but just to get the general idea of the form of these defences. I could list several examples of this type of defence shown on effigies and other works of art, but it would detract from this thread. I believe the brasses of William de Setvans and Sir William fitz Ralph are good examples. They definitely show a padded garment worn above the poleyn. It only shows slightly from beneath the gambeson (or aketon), but it's there.

What I am describing is definitely made from strips of some material, most probably metal, attached to a backing material. Several German effigies, and a few English and Italian, show this sort of defence. It is usually worn as a supplement to the mail sleeves and chausses. If you look carefully at some of the photos of the sculptures (the figure on the wooden Levitic Pew is a good example), you can clearly see that the splints stand above the backing material. There is no reason to believe that these were constructed with splints alternating on the outside and the inside; this seems an awkward configuration at best. I wish I could post photos of what I am talking about, but unfortunately I have the type of scanner that only takes single pages, and I don't want to destroy my various books. I would suggest that you talk a look at some of the photos yourself; I tried to list the books I used for the sources of my information.

I also must disagree with your assessment that the studs or rivets always hold plates beneath the backing material. The ones that show splints (and these are indeed splints, like I already said, they stand proud from the backing material in the better sculptures and effigies) and studs or disks are in the minority, but they do exist. The effigy of Gunther von Schwarzberg is a good example. If you have access to the book, take a look at the colour plate by Angus McBride in Christopher Gravett's Osprey book German Medieval Armies 1300-1500 that shows von Schwarzberg. It gives a good idea of what the greaves may have actually looked like. I know Osprey books are sometimes suspect; but that particular reconstruction is taken directly off the effigy. The greaves, rerebraces, and vambraces definitely consist of vertical splints alternating with vertical rows of studs or disks. There is no reason to believe that the studs or disks are attached to larger plates underneath; many of the German effigies lack any sign of material other than the backing material between the splints. There is also no reason to believe that the Acciaioli effigy has any plates beneath the backing material. It appears that this idea is similar to the early coat of plates or reinforced surcoat where the plates did not overlap. Perhaps they felt some form of reinforcement was better than none!

I am not alone in my belief that these effigies show "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour; I am just following what others that have studied the actual effigies, like David Nicolle, have said about the armours' apparent construction. Nicolle and Gravett, as well as Hefner-alteneck and Ashdown (although the accuracy of the interpretations by these earlier authors may be a bit suspect) have all interpreted the armour the same way.

Perhaps it really just the name were disagreeing about; what if I called these armours on the German effigies merely "splinted armour"?

Oh, by the way, Rene d'Anjou's treatise on tournaments showed leather (cuir bouilli) full vambraces that were reinforced with cords. I've heard of a similar configuration, but reinforced with wooden splints. Perhaps this is a late survival for the tournament of the same sort of idea that I am describing.

I hope this clarifies my position regarding these 14th century German effigies. Again, maybe if you could see what I was talking about, it might help to clarify the matter.

Oh, and in the case of the 14th century German effigies, I'm not saying that it was ever merely just studded. I am saying that you occasionally would see a "studded and splinted" configuration alongside the more usual "splinted".

A final note; keep in mind that these "splinted" armours probably had formed or hardened leather as a backing material. The metal bits were just extra reinforcements. The warrior with the probable leather vambrace with splints depicted in Breisgau Cathedral is a good example of how little metal may actually have gone into the construction of the armour pieces. The splints are there, but so narrow and widely spaced that they couldn't have offered a great deal of added protection.

I hope this made sense!

Stay safe!

Hello Richard,

You mention several splinted armours without visible rivets. Any ideas whats holding the plates on in those cases?

Also, is there a possibility that the 'disks' are large, decorative rivets for attaching internal plates?

Thanks of the information you provide.

-Steven

You mention several splinted armours without visible rivets. Any ideas whats holding the plates on in those cases?

Also, is there a possibility that the 'disks' are large, decorative rivets for attaching internal plates?

Thanks of the information you provide.

-Steven

Hello all!

Steven,

Since no pieces of this "splinted" armour have survived, we have to rely on interpretations of the brasses, effigies, and other sculptures to gain an understanding of construction. Perhaps the artists felt that the rivets were not a detail worth showing. Or, perhaps the rivets were ground flush with the splints. Also, I believe that the cord or wood splint reinforcements on the cuir bouilli vambraces in Rene D'Anjou's tournament treatise might have been glued or sewn on. The Osprey book Knights at Tournament by Christopher Gravett shows a color plate of knights in a mid 15th century melee with one knight wearing a vambrace constructed in such a manner. I suppose that the splints may have been glued on to the leather backing.

Dan Howard believes that studs must represent larger pieces of metal beneath the backing material, but I'm not so sure. More of the German effigies show vertical splints only, only a few show studs, rivets, or disks as well. The "studs" on the Schwarzburg effigy actually appear to be flat disks, spaced fairly close together. There are far more than would be needed to hold splints or plates inside. I think they might just be a case of adding a little bit more metal to the backing. Many more effigies show splints alone, with no trace of rivets or other evidence to suggest splints inside as well as outside. If they commonly mounted plates on the inside of the backing material as well as the outside, I think that rivets or something like that in the spaces between the visible splints would have been more common. Like I said earlier, "splinted" armour like favoured in 14th century Germany was probably attached to a leather backing; some of the photos of the effigies show that the backing material itself had a bit of thickness to it. The leather would actually be a part of the supplementary protection provided by these pieces. I think the effigy of Dieter von Hohenberg, with the splints clearly separate and attached by visible straps, proves that these German armours did not always offer "full" coverage. I believe the idea is the same behind the 15th century "jack chains" on the padded jacks of some common soldiers; a bit of extra protection was better than none! A few of the splints on the German effigies, those without a backing, look remarkable similar to the later "jack chains".

Oh, a final note about these "splinted armours". I am not saying that they were a perfect defence; if they were, they would never have been replaced with the "all white" harness of the 15th century. I am suggesting that the armourers of the 14th century experimented with a variety of styles and materials before they got it right. After all, the late 13th and early 14th centuries are known as a period of experimentation in armour!

I hope this clarifies things a bit. I wish I could say for certain what construction technique was used, but I suspect it varied a bit anyway!

Stay safe!

Richard

| Steven H wrote: |

|

You mention several splinted armours without visible rivets. Any ideas whats holding the plates on in those cases? Also, is there a possibility that the 'disks' are large, decorative rivets for attaching internal plates? Thanks of the information you provide. |

Steven,

Since no pieces of this "splinted" armour have survived, we have to rely on interpretations of the brasses, effigies, and other sculptures to gain an understanding of construction. Perhaps the artists felt that the rivets were not a detail worth showing. Or, perhaps the rivets were ground flush with the splints. Also, I believe that the cord or wood splint reinforcements on the cuir bouilli vambraces in Rene D'Anjou's tournament treatise might have been glued or sewn on. The Osprey book Knights at Tournament by Christopher Gravett shows a color plate of knights in a mid 15th century melee with one knight wearing a vambrace constructed in such a manner. I suppose that the splints may have been glued on to the leather backing.

Dan Howard believes that studs must represent larger pieces of metal beneath the backing material, but I'm not so sure. More of the German effigies show vertical splints only, only a few show studs, rivets, or disks as well. The "studs" on the Schwarzburg effigy actually appear to be flat disks, spaced fairly close together. There are far more than would be needed to hold splints or plates inside. I think they might just be a case of adding a little bit more metal to the backing. Many more effigies show splints alone, with no trace of rivets or other evidence to suggest splints inside as well as outside. If they commonly mounted plates on the inside of the backing material as well as the outside, I think that rivets or something like that in the spaces between the visible splints would have been more common. Like I said earlier, "splinted" armour like favoured in 14th century Germany was probably attached to a leather backing; some of the photos of the effigies show that the backing material itself had a bit of thickness to it. The leather would actually be a part of the supplementary protection provided by these pieces. I think the effigy of Dieter von Hohenberg, with the splints clearly separate and attached by visible straps, proves that these German armours did not always offer "full" coverage. I believe the idea is the same behind the 15th century "jack chains" on the padded jacks of some common soldiers; a bit of extra protection was better than none! A few of the splints on the German effigies, those without a backing, look remarkable similar to the later "jack chains".

Oh, a final note about these "splinted armours". I am not saying that they were a perfect defence; if they were, they would never have been replaced with the "all white" harness of the 15th century. I am suggesting that the armourers of the 14th century experimented with a variety of styles and materials before they got it right. After all, the late 13th and early 14th centuries are known as a period of experimentation in armour!

I hope this clarifies things a bit. I wish I could say for certain what construction technique was used, but I suspect it varied a bit anyway!

Stay safe!

Richard

Last edited by Richard Fay on Wed 18 Oct, 2006 8:23 am; edited 1 time in total

Greetings,

I've just stumbled upon your site here, and I'm finding it most enjoyable. I do wish there were more pictures. The information is wonderfull and I can almost picture what is being talked about in my head, but the pictures would definatly help. I do understand greatly that it isn't worth destroying your books to put through a single sheet scanner. That would be heresy as far as I'm concerned. :D If you have a digital camera though and can upload pics to your computer you can always take a picture of the page in the book. I know I know sounds really simple, but it took me a few years to figure out that trick. :D

I probably won't be posting much for awhile, there is quite a lot of information to digest, but look forward to maybe joining in on conversations more later, or I might chime in when my little bit of experiance might seem relevant.

Josh

PS Hopefully I didn't miss the new members introduce yourself here thread, and have just made a jack of myself. :D

I've just stumbled upon your site here, and I'm finding it most enjoyable. I do wish there were more pictures. The information is wonderfull and I can almost picture what is being talked about in my head, but the pictures would definatly help. I do understand greatly that it isn't worth destroying your books to put through a single sheet scanner. That would be heresy as far as I'm concerned. :D If you have a digital camera though and can upload pics to your computer you can always take a picture of the page in the book. I know I know sounds really simple, but it took me a few years to figure out that trick. :D

I probably won't be posting much for awhile, there is quite a lot of information to digest, but look forward to maybe joining in on conversations more later, or I might chime in when my little bit of experiance might seem relevant.

Josh

PS Hopefully I didn't miss the new members introduce yourself here thread, and have just made a jack of myself. :D

Hello all!

Josh, welcome to the forum! I'm fairly new here, too, but not new to the obsession with arms and armour! :D

I wish I could post pictures. Maybe someone else will get a chance to. My digital camera is not good for close-ups (or indoors, for that matter), so your idea won't work with my equipment. Thanks for the suggestion, though!

I could draw what I've been talking about, but I don't think that would really aid in the discussion much. I'll have to think about it a bit.

Again, welcome aboard, and enjoy! (I know I've been enjoying myself!) :)

Josh, welcome to the forum! I'm fairly new here, too, but not new to the obsession with arms and armour! :D

I wish I could post pictures. Maybe someone else will get a chance to. My digital camera is not good for close-ups (or indoors, for that matter), so your idea won't work with my equipment. Thanks for the suggestion, though!

I could draw what I've been talking about, but I don't think that would really aid in the discussion much. I'll have to think about it a bit.

Again, welcome aboard, and enjoy! (I know I've been enjoying myself!) :)

Greetings,

Thank you Richard. I know what you mean about it being hard to take pictures with a digital camera, at times they can be very finicky. I often have trouble getting good detailed shots of my maile.

Back to the topic at hand. I'm assuming what you mean by splints is narrow metal plates. I've heard that they can be sewn into pockets on the fabric. Thus the artist might show the raise where the plate is sewn in but not neccessarily the stitching of the pocket.

Josh

Thank you Richard. I know what you mean about it being hard to take pictures with a digital camera, at times they can be very finicky. I often have trouble getting good detailed shots of my maile.

Back to the topic at hand. I'm assuming what you mean by splints is narrow metal plates. I've heard that they can be sewn into pockets on the fabric. Thus the artist might show the raise where the plate is sewn in but not neccessarily the stitching of the pocket.

Josh

Hello all!

Josh,

This could very well be the case on some of the armours that have wide splints with little backing material between them. Although Osprey Publishing colour plate reconstructions are sometimes controversial in their details, they show just such a type of limb armour on a sergeant from Champagne, c. 1360, and a Rennes militiaman, c. 1370, in the book French Armies of the Hundred Years War by David Nicolle. On the same plate as the sergeant, they also show a northern French militiaman with a vambrace of splints of metal attached on the outside of a leather backing.

Some of the splints on the German effigies are narrow and quite widely spaced. I think it's clear that what were probably metal strips were only an addition to the protective qualities of the backing material, most likely leather. The carving depicting the sleeping guards at the Holy Sepulcher shows one soldier with extremely widely spaced, narrow splints on a vambrace. The vambrace follows the curvature of the arm and closes with straps and buckles on the inside of the arm. I believe the most likely interpretation of this piece is a formed or hardened leather vambrace with narrow metal strips to act as reinforcements or stiffeners. The Osprey book Knights at Tournament by Christopher Gravett describes the cuir bouilli vambraces for the tournament from Rene D'Anjou's treatise on the tournament as being stiffened by sticks glued to them, but it looks more like heavy cords in the illustration. The book Tournament by Richard Barber and Juliet Barker shows the actual images from the treatise, and the reinforcements (or decoration?) on the vambraces look more like cords in the original. Still, the general layout looks similar to the earlier splinted armour popular in 14th century Germany.

I suspect that the actual construction details varied, with many methods being used. There was no standardization as such during the 14th century, at least not until later in the century. Even then, German armour was often different from that used in the rest of Europe.

Still, what you described was used in some 15th century jacks. It is a possibility, at least for some of the "splinted" armours!

Stay safe!

| Josh B wrote: |

|

Back to the topic at hand. I'm assuming what you mean by splints is narrow metal plates. I've heard that they can be sewn into pockets on the fabric. Thus the artist might show the raise where the plate is sewn in but not neccessarily the stitching of the pocket. |

Josh,

This could very well be the case on some of the armours that have wide splints with little backing material between them. Although Osprey Publishing colour plate reconstructions are sometimes controversial in their details, they show just such a type of limb armour on a sergeant from Champagne, c. 1360, and a Rennes militiaman, c. 1370, in the book French Armies of the Hundred Years War by David Nicolle. On the same plate as the sergeant, they also show a northern French militiaman with a vambrace of splints of metal attached on the outside of a leather backing.

Some of the splints on the German effigies are narrow and quite widely spaced. I think it's clear that what were probably metal strips were only an addition to the protective qualities of the backing material, most likely leather. The carving depicting the sleeping guards at the Holy Sepulcher shows one soldier with extremely widely spaced, narrow splints on a vambrace. The vambrace follows the curvature of the arm and closes with straps and buckles on the inside of the arm. I believe the most likely interpretation of this piece is a formed or hardened leather vambrace with narrow metal strips to act as reinforcements or stiffeners. The Osprey book Knights at Tournament by Christopher Gravett describes the cuir bouilli vambraces for the tournament from Rene D'Anjou's treatise on the tournament as being stiffened by sticks glued to them, but it looks more like heavy cords in the illustration. The book Tournament by Richard Barber and Juliet Barker shows the actual images from the treatise, and the reinforcements (or decoration?) on the vambraces look more like cords in the original. Still, the general layout looks similar to the earlier splinted armour popular in 14th century Germany.

I suspect that the actual construction details varied, with many methods being used. There was no standardization as such during the 14th century, at least not until later in the century. Even then, German armour was often different from that used in the rest of Europe.

Still, what you described was used in some 15th century jacks. It is a possibility, at least for some of the "splinted" armours!

Stay safe!

A big problem many people here are running into here are making assumptions based solely on the artists rendition of a piece. We've seen time and time again artists who have used artistic license or were just too lazy to add in many of the needed details. You might not see studs on a boning because the rivet was well mated. You might cording when in fact it was decorative metal. And lets not get into the fact that sometimes people come up with weird ways to augment armor which may or may not work. Add that to an artist who might not understand the significance (or is just underpaid) and you might end up looking at klingon type armor.

Oh and Richard. You say you disagree with the assessment that studs always hold plates beneath the backing material based on comparisons with other effigies. However, you do forget to add in one factor which is style of that time. If we are going to theorize then we must theorize based on other flagrant examples that studs alone may have been in major vogue at the time which would explain why you see no hint of splints on the items themselves.

Oh and Richard. You say you disagree with the assessment that studs always hold plates beneath the backing material based on comparisons with other effigies. However, you do forget to add in one factor which is style of that time. If we are going to theorize then we must theorize based on other flagrant examples that studs alone may have been in major vogue at the time which would explain why you see no hint of splints on the items themselves.

Hello all!

Randall,

I'm not quite sure I'm following your train of thought. I do understand the weaknesses of using art to interpret construction; I think I did make it clear we can only arrive at assumptions based on what is seen on the effigies. Unfortunately, we don't have any extant pieces of "stud and splint" armour to examine, so we must rely on the art alone. However, many of the effigies and brasses show great detail, and many do match pretty closely to extant armour, so I think using these particular pieces of art as a tool is perfectly valid.

I suggest that the studs may not hold anything beneath the cover material based on a close examination of various photos and high-quality artistic reproductions (that pretty well exactly match the photos when compared side-by-side) of the various effigies. I believe I already mentioned that most of the German effigies so no trace of studs between or on the splints. Perhaps they were painted on and now lost, we really can't be sure. Some show definite carved "rivets" on the splints, but nothing on the backing material between the splints. Also, keep in mind that leather was probably most likely used as the backing material. These "stud and splint" armours are more like "reinforced or stiffened" formed or hardened leather armours. I believe the metal was only an additional protective measure.

Can I say for sure that there were no plates inside the cover? No, I cannot, but it seems unlikely to me. Am I alone in my proposed construction of these pieces? Again, no, others who have degrees or otherwise careers studying these things have reached the same conclusion. Christopher Gravett shows a drawing of a knight arming, wearing splint vambraces and greaves, in German Medieval Armies 1300-1500. In the same Osprey book, he describes the effigy of Burkhard von Steinberg as having forearms protected by "stud-and-splint" armour of metal strips attached to leather and reinforced with rivets. One of the colour plates by Angus McBride found in the same book contains a reconstruction based on the effigy of Gunther von Schwarzberg. The description of the plate states that von Schwarzberg is wearing "stud and splint" armour on his limbs; armour in which the strips are reinforced by rivets. (And, like I have said previously, the "rivets" on the von Schwarzberg effigy are more like very closely spaced disks, almost touching each other and the adjacent splints. There would be no real need for metal underneath, it would probably create an awfully heavy piece of armour if it bore strips both on the inside and the outside, along with the "disks".) There is a knight in the colour plates in Armies of Medieval Burgundy 1364-1477 by Nicholas Michael, plates by G. A. Embleton, that wears "splinted" greaves. The description states that the greaves are made of leather reinforced with rivetted metal strips. The strips are obviously on the outside. As I have already mentioned previously, David Nicolle also interprets this armour the same way. Earlier authors, such as Charles Henry Ashdown and J.H. Hefner-Alteneck did the same.

Yes, style can be a factor, so we must be careful, but few of the effigies show any "flagrant" stylistic tendencies. There might be a few "stylized" details rather than "authentic" details, but most look like fairly reliable representations of the armour worn at the time. Should we discount the study of the numerous 14th and 15th century English brasses because they are forms of art? Of course not, the study of the brasses is a perfectly valid tool in the study of armour! Do the superb effigies of the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral, or Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, at Warwick contain "fanciful" or "stylized" elements? Of course they don't, they are exacting representations of the armour of their time!

One other thing to add, there is evidence that leather was seen as a proper material for limb armour in the 14th century. An armorial treatise of the early 14th century describes the arming of the knight for tournament, war, and joust. It describes how he is to put plates of metal or cuir bouilli (hardened leather) on his calves and thighs. There are also a few 14th century manuscript images, such one showing jousting knights in the Manessa Codex and another showing jousting knights in the Romance of Alexander that show what certainly appears to be leather (brown in one case, black in the other, and both tied shut with laces) greaves. If leather alone was seen as sufficient protection, I don't see why we have to interpret the "stud-and-splint" armours as having splints both outside and inside. I think it's overkill!

I hope this clarified my position. I've tried to gather and study a lot of information to arrive at my assumption. Admittedly, since a lot is based on the interpretation of art, there will always be conflicting interpretations. That's what makes a forum such as this such a wonderful place, we can carry on a discussion regarding the various interpretations!

Stay safe!

| Randall Sanchez wrote: |

|

Oh and Richard. You say you disagree with the assessment that studs always hold plates beneath the backing material based on comparisons with other effigies. However, you do forget to add in one factor which is style of that time. If we are going to theorize then we must theorize based on other flagrant examples that studs alone may have been in major vogue at the time which would explain why you see no hint of splints on the items themselves. |

Randall,

I'm not quite sure I'm following your train of thought. I do understand the weaknesses of using art to interpret construction; I think I did make it clear we can only arrive at assumptions based on what is seen on the effigies. Unfortunately, we don't have any extant pieces of "stud and splint" armour to examine, so we must rely on the art alone. However, many of the effigies and brasses show great detail, and many do match pretty closely to extant armour, so I think using these particular pieces of art as a tool is perfectly valid.

I suggest that the studs may not hold anything beneath the cover material based on a close examination of various photos and high-quality artistic reproductions (that pretty well exactly match the photos when compared side-by-side) of the various effigies. I believe I already mentioned that most of the German effigies so no trace of studs between or on the splints. Perhaps they were painted on and now lost, we really can't be sure. Some show definite carved "rivets" on the splints, but nothing on the backing material between the splints. Also, keep in mind that leather was probably most likely used as the backing material. These "stud and splint" armours are more like "reinforced or stiffened" formed or hardened leather armours. I believe the metal was only an additional protective measure.

Can I say for sure that there were no plates inside the cover? No, I cannot, but it seems unlikely to me. Am I alone in my proposed construction of these pieces? Again, no, others who have degrees or otherwise careers studying these things have reached the same conclusion. Christopher Gravett shows a drawing of a knight arming, wearing splint vambraces and greaves, in German Medieval Armies 1300-1500. In the same Osprey book, he describes the effigy of Burkhard von Steinberg as having forearms protected by "stud-and-splint" armour of metal strips attached to leather and reinforced with rivets. One of the colour plates by Angus McBride found in the same book contains a reconstruction based on the effigy of Gunther von Schwarzberg. The description of the plate states that von Schwarzberg is wearing "stud and splint" armour on his limbs; armour in which the strips are reinforced by rivets. (And, like I have said previously, the "rivets" on the von Schwarzberg effigy are more like very closely spaced disks, almost touching each other and the adjacent splints. There would be no real need for metal underneath, it would probably create an awfully heavy piece of armour if it bore strips both on the inside and the outside, along with the "disks".) There is a knight in the colour plates in Armies of Medieval Burgundy 1364-1477 by Nicholas Michael, plates by G. A. Embleton, that wears "splinted" greaves. The description states that the greaves are made of leather reinforced with rivetted metal strips. The strips are obviously on the outside. As I have already mentioned previously, David Nicolle also interprets this armour the same way. Earlier authors, such as Charles Henry Ashdown and J.H. Hefner-Alteneck did the same.

Yes, style can be a factor, so we must be careful, but few of the effigies show any "flagrant" stylistic tendencies. There might be a few "stylized" details rather than "authentic" details, but most look like fairly reliable representations of the armour worn at the time. Should we discount the study of the numerous 14th and 15th century English brasses because they are forms of art? Of course not, the study of the brasses is a perfectly valid tool in the study of armour! Do the superb effigies of the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral, or Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, at Warwick contain "fanciful" or "stylized" elements? Of course they don't, they are exacting representations of the armour of their time!

One other thing to add, there is evidence that leather was seen as a proper material for limb armour in the 14th century. An armorial treatise of the early 14th century describes the arming of the knight for tournament, war, and joust. It describes how he is to put plates of metal or cuir bouilli (hardened leather) on his calves and thighs. There are also a few 14th century manuscript images, such one showing jousting knights in the Manessa Codex and another showing jousting knights in the Romance of Alexander that show what certainly appears to be leather (brown in one case, black in the other, and both tied shut with laces) greaves. If leather alone was seen as sufficient protection, I don't see why we have to interpret the "stud-and-splint" armours as having splints both outside and inside. I think it's overkill!

I hope this clarified my position. I've tried to gather and study a lot of information to arrive at my assumption. Admittedly, since a lot is based on the interpretation of art, there will always be conflicting interpretations. That's what makes a forum such as this such a wonderful place, we can carry on a discussion regarding the various interpretations!

Stay safe!

Last edited by Richard Fay on Wed 18 Oct, 2006 2:52 pm; edited 1 time in total

Hello all!

Okay, my wife's gonna get mad at me for doing this, since she knows how precious my books are to me (more precious than my MRL swords, certainly), but I felt that images might help the discussion. Since my copy of Henry Trivick's The Picture Book of Brasses in Gilt was already cut-up a bit by a previous owner (a couple pages were missing, presumably cut-out and used as framed art), I felt it wouldn't do too much damage cutting out a couple more. Since I have the frustrating sort of scanner that only scans single-page documents, that's what I had to do to post the pictures. That's also why I didn't post any pictures of the German effigies; I refuse to damage any more of my books!

Anyway, I managed to scan the plates from Trivick showing the de Stapleton and the Cheyne brasses. Note on the Stapleton brass the torso defence and thigh defences display rivets, but no lines. I think it's fairly safe to assume that this depicts a brigandine or coat-of-plate style of construction; overlapping plates or scales rivetted beneath a cloth (or sometimes leather, perhaps) cover. Note the lower legs are defended by strips of material rivetted to a fairly stiff backing material. The fact that the material is somewhat stiff can be deduced by how it stands up away from the foot. The leg defence can be interpreted as metal strips rivetted to leather greaves.

Note also the Cheyne brass wears similar (almost identical) defences on the lower legs. Again, it consists of strips rivetted to a backing, although the "stiffness" of the backing material is not as clearly evident as on the Stapleton brass. Again, Cheyne wears cuisses constructed just like a coat-of-plates or a brigandine coat.

Many of the German effigies depict greaves or complete armour for the limbs constructed in a very similar manner, although some don't show obvious rivets. The German effigies and sculptures do show this armour in three dimensions, something which the English brasses obviously do not. On the German sculptures and effigies, the "splints" (the rivetted strips on the English brasses) do definitely stand "proud" from the backing material.

I have also included a photo of my attempt at recreating the "studded and splinted" greaves on such effigies as Gunther von Schwarzberg. It would never be acceptable to a living history group since I was forced to use some modern materials to keep cost down, but it follows the general form. The splints are rivetted on; I used "rapid rivets" to save time and money. The "studs" are round spots from a leather retailer; if I was to make it more "authentic", I would have used disks just like that depicted on Schwarzberg's effigy, not "spots". I had the round spots readily available, so that's what I used. The greaves originally began life as full leather greaves; that's why they are in three pieces. (I originally rivetted two pieces together along one side and laced them shut on the other, but then decided that I would rather have a strap and buckle closure down the back.) I would imagine "authentic" greaves would have been made with only one piece of leather. Finally, if I was to make these again, I wouldn't use "wax-hardened leather", but that was the technique I knew about at the time. All disclaimers aside, they look generally similar to the German "studded and splinted" greaves.

A final note; I would still love to see any images of the German effigies showing "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour posted on this thread! It might help the discussion if we had images to look at!

Stay safe!

Attachment: 51.37 KB

Attachment: 51.37 KB

Sir Miles de Stapleton and wife Joan, 1364.

Attachment: 20.47 KB

Attachment: 20.47 KB

Sir Thomas Cheyne, 1368.

Attachment: 39.12 KB

Attachment: 39.12 KB

Richard's studded and splinted greaves, back and front.

Okay, my wife's gonna get mad at me for doing this, since she knows how precious my books are to me (more precious than my MRL swords, certainly), but I felt that images might help the discussion. Since my copy of Henry Trivick's The Picture Book of Brasses in Gilt was already cut-up a bit by a previous owner (a couple pages were missing, presumably cut-out and used as framed art), I felt it wouldn't do too much damage cutting out a couple more. Since I have the frustrating sort of scanner that only scans single-page documents, that's what I had to do to post the pictures. That's also why I didn't post any pictures of the German effigies; I refuse to damage any more of my books!

Anyway, I managed to scan the plates from Trivick showing the de Stapleton and the Cheyne brasses. Note on the Stapleton brass the torso defence and thigh defences display rivets, but no lines. I think it's fairly safe to assume that this depicts a brigandine or coat-of-plate style of construction; overlapping plates or scales rivetted beneath a cloth (or sometimes leather, perhaps) cover. Note the lower legs are defended by strips of material rivetted to a fairly stiff backing material. The fact that the material is somewhat stiff can be deduced by how it stands up away from the foot. The leg defence can be interpreted as metal strips rivetted to leather greaves.

Note also the Cheyne brass wears similar (almost identical) defences on the lower legs. Again, it consists of strips rivetted to a backing, although the "stiffness" of the backing material is not as clearly evident as on the Stapleton brass. Again, Cheyne wears cuisses constructed just like a coat-of-plates or a brigandine coat.

Many of the German effigies depict greaves or complete armour for the limbs constructed in a very similar manner, although some don't show obvious rivets. The German effigies and sculptures do show this armour in three dimensions, something which the English brasses obviously do not. On the German sculptures and effigies, the "splints" (the rivetted strips on the English brasses) do definitely stand "proud" from the backing material.

I have also included a photo of my attempt at recreating the "studded and splinted" greaves on such effigies as Gunther von Schwarzberg. It would never be acceptable to a living history group since I was forced to use some modern materials to keep cost down, but it follows the general form. The splints are rivetted on; I used "rapid rivets" to save time and money. The "studs" are round spots from a leather retailer; if I was to make it more "authentic", I would have used disks just like that depicted on Schwarzberg's effigy, not "spots". I had the round spots readily available, so that's what I used. The greaves originally began life as full leather greaves; that's why they are in three pieces. (I originally rivetted two pieces together along one side and laced them shut on the other, but then decided that I would rather have a strap and buckle closure down the back.) I would imagine "authentic" greaves would have been made with only one piece of leather. Finally, if I was to make these again, I wouldn't use "wax-hardened leather", but that was the technique I knew about at the time. All disclaimers aside, they look generally similar to the German "studded and splinted" greaves.

A final note; I would still love to see any images of the German effigies showing "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour posted on this thread! It might help the discussion if we had images to look at!

Stay safe!

Sir Miles de Stapleton and wife Joan, 1364.

Sir Thomas Cheyne, 1368.

Richard's studded and splinted greaves, back and front.

Modern production obviously but you might like looking at these by Mercenary's Tailor:

http://www.merctailor.com/catalog/product_inf...cts_id=101

http://www.merctailor.com/catalog/product_inf...cts_id=100

http://www.merctailor.com/catalog/product_inf...ucts_id=44

http://www.merctailor.com/catalog/product_inf...cts_id=101

http://www.merctailor.com/catalog/product_inf...cts_id=100

http://www.merctailor.com/catalog/product_inf...ucts_id=44

richard, in some circles its believed that there are 2 sets of splints. one inside the material and one outside. thus showing only rivet heads.

I believe I said that in my first post. The splints alternate inside and outside.

Hello all!

I suppose it's possible, but why do you believe it's necessary? My belief is that the backing material alone would be considered as part of the defense, certainly if it was made of formed or hardened leather. What benefit would be gained from "inside and outside" versus "outside only"? I think the splints are just a reinforcement to the leather, not the main protection. Wouldn't a few splints aid against a slash, if not a thrust or arrow hit? Wouldn't the idea of a few metal splints on the outside of a leather greave or vambrace be similar to the idea of 15th century "jack chains", a bit of reinforcement is better than none?

I have reason for suspecting that the splints are on the outside only, and I have voiced them repeatedly. It's only an interpretation, I know, so it is subject to debate, but I try to look at many of the effigies and compare examples.

The effigies of Heinrich of Seinsheim, Conrad of Seinsheim, Huglin of Shoeneck, and Gottfried, Count of Arensberg show no trace of rivets or other visible sign of splints alternating on the inside as well as those visible on the outside. This could be a case of the evidence being lost over time, but I don't believe that is the case with all. The effigy of the Count of Arensberg clearly shows rivets on the splints on the outside of the vambraces, but no sign of rivets for splints underneath. This is the same configuration on the English brasses, rivetted splints with no trace of rivets between. The effigy of Huglin of Schoeneck clearly shows rivets on the "brigandine" cuisses on his thighs and the armour on his feet, but no rivets at all on the greaves.

Furthermore, some German effigies show clear "splints" worn without a backing. The effigy of the Count of Arensberg already mentioned wears narrow plates laced onto the upper sleeves of his haubergeon, and narrow plates attached in some way not visible to the front of his shins, over his mail chausses. (In both cases, the plates are narrow enough to be called splints; about 3 inches wide at best.) The effigy of Hartmann of Kroneberg shows greaves made of splints held together by straps clearly visible in the gap between the plates. There are no apparent plates "underneath". The effigy of the Margrave Rudolph IV of Baden-Durlach, shown in a photo, not an "artistic rendition" in Tanneberg 1410: Disaster for the Teutonic Knights by Stephen Turnbull, clearly shows narrow plates attached to each other and a rondel at the elbow, worn over mail. The plates could definitely be classified as "splints", they are that narrow! It appears that the Germans sometimes felt a bit of plate was better than none, and clearly didn't always wear "complete plate" with full coverage in the 14th century.

If you have evidence that supports the existence of plates both on the outside of the backing material and on the inside, I would love to hear it, or better yet see it. Otherwise, you must admit that it is as much of an assumption as suggesting that there were no plates beneath the backing material. (Yes, I admit that I am making an assumption, but it's an assumption that comes from years of studying the images and descriptions and reading volumes about the effigies and brasses.)

One last thing, I'm not saying, nor ever have said, that "studded and splinted" or "splinted" armour was a perfect defence. If it had been, knights throughout Europe would never have adopted the "all white" harness. What I am saying is that they experimented with a lot of different designs before arriving at the "perfect (?) armour". Clearly German knights sometimes favoured a lighter protection over some of their contemporaries. Perhaps if they had encountered the longbow as frequently as the knights of France, then maybe they would have adopted a more complete plate protection sooner! (Just a thought!)

I believe I have said pretty much all I have to say regarding this issue, unless someone comes up with some new descriptions or pictures. I would just be repeating myself if I said any more!

Stay safe!

| Dan Howard wrote: |

|

I believe I said that in my first post. The splints alternate inside and outside. |

I suppose it's possible, but why do you believe it's necessary? My belief is that the backing material alone would be considered as part of the defense, certainly if it was made of formed or hardened leather. What benefit would be gained from "inside and outside" versus "outside only"? I think the splints are just a reinforcement to the leather, not the main protection. Wouldn't a few splints aid against a slash, if not a thrust or arrow hit? Wouldn't the idea of a few metal splints on the outside of a leather greave or vambrace be similar to the idea of 15th century "jack chains", a bit of reinforcement is better than none?

I have reason for suspecting that the splints are on the outside only, and I have voiced them repeatedly. It's only an interpretation, I know, so it is subject to debate, but I try to look at many of the effigies and compare examples.

The effigies of Heinrich of Seinsheim, Conrad of Seinsheim, Huglin of Shoeneck, and Gottfried, Count of Arensberg show no trace of rivets or other visible sign of splints alternating on the inside as well as those visible on the outside. This could be a case of the evidence being lost over time, but I don't believe that is the case with all. The effigy of the Count of Arensberg clearly shows rivets on the splints on the outside of the vambraces, but no sign of rivets for splints underneath. This is the same configuration on the English brasses, rivetted splints with no trace of rivets between. The effigy of Huglin of Schoeneck clearly shows rivets on the "brigandine" cuisses on his thighs and the armour on his feet, but no rivets at all on the greaves.

Furthermore, some German effigies show clear "splints" worn without a backing. The effigy of the Count of Arensberg already mentioned wears narrow plates laced onto the upper sleeves of his haubergeon, and narrow plates attached in some way not visible to the front of his shins, over his mail chausses. (In both cases, the plates are narrow enough to be called splints; about 3 inches wide at best.) The effigy of Hartmann of Kroneberg shows greaves made of splints held together by straps clearly visible in the gap between the plates. There are no apparent plates "underneath". The effigy of the Margrave Rudolph IV of Baden-Durlach, shown in a photo, not an "artistic rendition" in Tanneberg 1410: Disaster for the Teutonic Knights by Stephen Turnbull, clearly shows narrow plates attached to each other and a rondel at the elbow, worn over mail. The plates could definitely be classified as "splints", they are that narrow! It appears that the Germans sometimes felt a bit of plate was better than none, and clearly didn't always wear "complete plate" with full coverage in the 14th century.

If you have evidence that supports the existence of plates both on the outside of the backing material and on the inside, I would love to hear it, or better yet see it. Otherwise, you must admit that it is as much of an assumption as suggesting that there were no plates beneath the backing material. (Yes, I admit that I am making an assumption, but it's an assumption that comes from years of studying the images and descriptions and reading volumes about the effigies and brasses.)

One last thing, I'm not saying, nor ever have said, that "studded and splinted" or "splinted" armour was a perfect defence. If it had been, knights throughout Europe would never have adopted the "all white" harness. What I am saying is that they experimented with a lot of different designs before arriving at the "perfect (?) armour". Clearly German knights sometimes favoured a lighter protection over some of their contemporaries. Perhaps if they had encountered the longbow as frequently as the knights of France, then maybe they would have adopted a more complete plate protection sooner! (Just a thought!)

I believe I have said pretty much all I have to say regarding this issue, unless someone comes up with some new descriptions or pictures. I would just be repeating myself if I said any more!

Stay safe!

Hello again!

Jean,

I wanted to thank you for the links! I had seen these before, but they had slipped my mind. They are a "modern interpretation" of what I have been talking about. However, I feel that the medieval "studded and splinted" armour would have had formed or hardened leather as a backing, not latigo.

Thanks again!

Stay safe!

Jean,

I wanted to thank you for the links! I had seen these before, but they had slipped my mind. They are a "modern interpretation" of what I have been talking about. However, I feel that the medieval "studded and splinted" armour would have had formed or hardened leather as a backing, not latigo.

Thanks again!

Stay safe!

Last edited by Richard Fay on Thu 19 Oct, 2006 1:11 pm; edited 1 time in total

Hello all!

Okay, this is likely to be my last post regarding the topic of "studded and splinted" armour. (I know, some of you are probably saying "shut up already!") However, I thought a list of the resources I used researching this subject might be appreciated. I thought it may be useful to those that wish a further study regarding this subject. I know I already mentioned some in my previous posts. I've included some brief notes regarding the information contained in each source, and the apparent reliability of that information. I'm sure at least some of these volumes could be found right here on the myArmoury bookstore! This way, anyone can purchase or otherwise obtain the books to view the images and read the descriptions for themselves, and reach their own conclusion regarding the true form of "studded and splinted" armour.

Balir, Claude European Armour Circa 1066 to Circa 1700 (1958).

Blair makes a brief mention of cuisses and greaves shown with longitudinal reinforcements used up to 1380, and has a photo of the effigy of Ritter Burkhard von Steinberg showing "studded and splinted" vambraces.

Martin, Paul Arms and Armour (1967).

Martin has a photo and several drawings of German sculptures showing "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour. He describes it as "iron-plated leather".

Nicolle, David Arms & Armour of the Crusading Era 1050-1350: Western Europe and the Crusader States (1999).

Nicolle shows many examples of German and Italian "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour. His drawings are simplified and lack detail, but they are numerous. His text entries for the illustrations are brief but concise and informative. Nicolle has spent years studying the effigies, brasses, and other artwork depicting arms and armour, as well as existing pieces. He interprets the limb protection on the von Schwarzberg effigy as being of "splinted and rivetted" construction, possible for reasons of weight or cost. In other words, it most likely didn't have plates beneath the cover if it was trying to reduce weight, since they would be superfluous.

Gravett, Christopher German Medieval Armies 1300-1500 (1985).

Gravett includes a reconstruction drawing of a mid-14th century knight arming. The knight wears greaves of metal splints on leather. He also includes a photo of the von Steinberg effigy, as well as a colour plate by Angus McBride depicting von Schwarzberg. He describes "splinted" armour as being metal attached to leather, and "studded and splinted" being of metal strips attached to leather and reinforced with rivets.

Norman, Vesey Arms and Armor (1964).

Norman shows photos of the effigies of Dieter von Hohenberg and Otto von Orlamunde. Von Hohenberg wears limb armour of narrow splints on a backing, von Orlamunde vambraces of wide splints. In his text, Norman describes the German greaves that consisted of several metal splints strapped over mail.

Ashdown, Charles Henry European Arms and Armor (first published in the early 20th century).

Care must be taken when relying on Ahsdown's descriptions; this book contains many outdated ideas. Still, his illustrations are very well done, and accurately match other sources. He illustrates the "splinted" armour found on the greaves depicted on the Stapleton and Cheyne brasses. He describes splinted armour as consisting of parallel bands of steel arranged in vertical lines embedded in "pourpoint" or affixed to cuir bouilli. (By the way, Ashdown coined the term "studded and splinted' for a period in English armour development, I certainly didn't invent the term!)

Hefner-Alteneck, J.H. Medieval Arms and Armor: a Pictorial Archive (first published in 1903).

Again, care must be taken when relying on Hefner-Alteneck's outdated descriptions. He describes a plethora of things as being made out of leather. However, his drawings show many of the German effigies, and closely match those that I have photos for as well. He describes splinted armour as leather covered with metal strips.

Rothero, Christopher Medieval Military Dress 1066-1500 (1983).

This book contains many colour plate reconstructions. One shows von Schwarzberg. Rothero describes the limb protection as consisting of rivets placed between longitudinal strips of metal.

Saxtorph, Niels M. Warriors and Weapons 3000 BC to AD 177 in Colour (1971).

Again, this book contains many colour reconstructions, some better than others. Some are outdated, but some are more accurate. Again, Saxtorph shows von Schwarzberg. He states that the limbs armour was of cuir-bouilli, grained and painted or the pattern made with metal rivets that served as reinforcements.

Stone, George Cameron A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in all Countries and in all Times (originally published in 1934).

This book is rather outdated, but it still contains some interesting information. Stone describes splinted armour as "armour made of narrow plates or splints rivetted together, or to a backing of cloth or leather, so as to be flexible. Similarly constructed armor was worn in Turkey and China". In the entry on armour, Stone shows a photograph of a Tibetan arm guard of leather strapped with iron. This bears an interesting resemblance to the "splinted" armours of 14th century Europe.

Lindholm, D. and D. Nicolle Medieval Scandinavian Armies 1300-1500 (2003).

one of the colour plates by Angus McBride depicts a couple of warriors wearing "splinted" greaves. One, based on the effigy of Duke Chritopher of Denmark (shown in a photo in the same book) has one very narrow vertical strip over the shin and two equally narrow horizantal strips rivetted onto what are apparently leather greaves. Another figure depicts a nobleman wearing greaves of long narrow iron strips rivetted to thick, brightly colored "stockings" of cloth (?) or leather.

Kelly, Frances M. and Randolph Schwabe A Short History of Costume and Armour 1066-1485 (originally published in 1931).

This books a bit outdated, but it does show a photo of the von Steinberg effigy which clearly shows that the legs are protected by splints separated by a bit of space and connected together with straps. If the greaves had gaps in the metal defence, why not the vambraces? It also descibes studs being combined with vertical bands of metal as a common defence for the limbs in the period 1350-1380.

I know there are probably a few I neglected to list (I believe there may be a few more Osprey titles that describe the same sort of thing), but I think this is a fairly good representation of the material I have looked at. I hope this helped someone in a further study of "studded and splinted" armour. At least it should clarify where I got my information from!

Stay safe!

Okay, this is likely to be my last post regarding the topic of "studded and splinted" armour. (I know, some of you are probably saying "shut up already!") However, I thought a list of the resources I used researching this subject might be appreciated. I thought it may be useful to those that wish a further study regarding this subject. I know I already mentioned some in my previous posts. I've included some brief notes regarding the information contained in each source, and the apparent reliability of that information. I'm sure at least some of these volumes could be found right here on the myArmoury bookstore! This way, anyone can purchase or otherwise obtain the books to view the images and read the descriptions for themselves, and reach their own conclusion regarding the true form of "studded and splinted" armour.

Balir, Claude European Armour Circa 1066 to Circa 1700 (1958).

Blair makes a brief mention of cuisses and greaves shown with longitudinal reinforcements used up to 1380, and has a photo of the effigy of Ritter Burkhard von Steinberg showing "studded and splinted" vambraces.

Martin, Paul Arms and Armour (1967).

Martin has a photo and several drawings of German sculptures showing "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour. He describes it as "iron-plated leather".

Nicolle, David Arms & Armour of the Crusading Era 1050-1350: Western Europe and the Crusader States (1999).

Nicolle shows many examples of German and Italian "splinted" or "studded and splinted" armour. His drawings are simplified and lack detail, but they are numerous. His text entries for the illustrations are brief but concise and informative. Nicolle has spent years studying the effigies, brasses, and other artwork depicting arms and armour, as well as existing pieces. He interprets the limb protection on the von Schwarzberg effigy as being of "splinted and rivetted" construction, possible for reasons of weight or cost. In other words, it most likely didn't have plates beneath the cover if it was trying to reduce weight, since they would be superfluous.

Gravett, Christopher German Medieval Armies 1300-1500 (1985).

Gravett includes a reconstruction drawing of a mid-14th century knight arming. The knight wears greaves of metal splints on leather. He also includes a photo of the von Steinberg effigy, as well as a colour plate by Angus McBride depicting von Schwarzberg. He describes "splinted" armour as being metal attached to leather, and "studded and splinted" being of metal strips attached to leather and reinforced with rivets.

Norman, Vesey Arms and Armor (1964).

Norman shows photos of the effigies of Dieter von Hohenberg and Otto von Orlamunde. Von Hohenberg wears limb armour of narrow splints on a backing, von Orlamunde vambraces of wide splints. In his text, Norman describes the German greaves that consisted of several metal splints strapped over mail.

Ashdown, Charles Henry European Arms and Armor (first published in the early 20th century).

Care must be taken when relying on Ahsdown's descriptions; this book contains many outdated ideas. Still, his illustrations are very well done, and accurately match other sources. He illustrates the "splinted" armour found on the greaves depicted on the Stapleton and Cheyne brasses. He describes splinted armour as consisting of parallel bands of steel arranged in vertical lines embedded in "pourpoint" or affixed to cuir bouilli. (By the way, Ashdown coined the term "studded and splinted' for a period in English armour development, I certainly didn't invent the term!)

Hefner-Alteneck, J.H. Medieval Arms and Armor: a Pictorial Archive (first published in 1903).

Again, care must be taken when relying on Hefner-Alteneck's outdated descriptions. He describes a plethora of things as being made out of leather. However, his drawings show many of the German effigies, and closely match those that I have photos for as well. He describes splinted armour as leather covered with metal strips.

Rothero, Christopher Medieval Military Dress 1066-1500 (1983).

This book contains many colour plate reconstructions. One shows von Schwarzberg. Rothero describes the limb protection as consisting of rivets placed between longitudinal strips of metal.

Saxtorph, Niels M. Warriors and Weapons 3000 BC to AD 177 in Colour (1971).

Again, this book contains many colour reconstructions, some better than others. Some are outdated, but some are more accurate. Again, Saxtorph shows von Schwarzberg. He states that the limbs armour was of cuir-bouilli, grained and painted or the pattern made with metal rivets that served as reinforcements.

Stone, George Cameron A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in all Countries and in all Times (originally published in 1934).

This book is rather outdated, but it still contains some interesting information. Stone describes splinted armour as "armour made of narrow plates or splints rivetted together, or to a backing of cloth or leather, so as to be flexible. Similarly constructed armor was worn in Turkey and China". In the entry on armour, Stone shows a photograph of a Tibetan arm guard of leather strapped with iron. This bears an interesting resemblance to the "splinted" armours of 14th century Europe.

Lindholm, D. and D. Nicolle Medieval Scandinavian Armies 1300-1500 (2003).

one of the colour plates by Angus McBride depicts a couple of warriors wearing "splinted" greaves. One, based on the effigy of Duke Chritopher of Denmark (shown in a photo in the same book) has one very narrow vertical strip over the shin and two equally narrow horizantal strips rivetted onto what are apparently leather greaves. Another figure depicts a nobleman wearing greaves of long narrow iron strips rivetted to thick, brightly colored "stockings" of cloth (?) or leather.

Kelly, Frances M. and Randolph Schwabe A Short History of Costume and Armour 1066-1485 (originally published in 1931).

This books a bit outdated, but it does show a photo of the von Steinberg effigy which clearly shows that the legs are protected by splints separated by a bit of space and connected together with straps. If the greaves had gaps in the metal defence, why not the vambraces? It also descibes studs being combined with vertical bands of metal as a common defence for the limbs in the period 1350-1380.

I know there are probably a few I neglected to list (I believe there may be a few more Osprey titles that describe the same sort of thing), but I think this is a fairly good representation of the material I have looked at. I hope this helped someone in a further study of "studded and splinted" armour. At least it should clarify where I got my information from!

Stay safe!

Page 1 of 1

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum