Jared;

Very good question there and it seems to me a viable if hard to prove either way theory.

On the other hand some more knowledgeable forum members may be able to quote historical sources.

If I remember correctly Gordon Frye has mentioned that the Spanish were very systematic in their record keeping of equipment issued to troops and expeditions.

I would assume that the richer nobles would be able to afford a complete harness but might, short of a major battle, use Helm, breast and back plate, gauntlets, all over maille or gambison ONLY.

The use of 3/4 or 1/2 seemed to have become more and more popular as full armour was slowly being phased out or going out of fashion.

At the beginning of the use of plate leg armour seems to have been adopted very early: I think this is because the legs when on horse back would be particularly vulnerable being for all practical purposed immobilized in the stirrups.

The arms even if only protected by maille sleeves and the hands gauntlets are at least mobile and can actively avoid blows.

I'm looking forward to what others will be able to contribute here: Should be interesting :cool:

| Tyler Weaver wrote: |

|

They were firing in organized three-rank volleys. This is 1575, about thirty years before Europeans started doing it with any kind of serious regularity. |

When I read the above "organized three-rank volleys", I immediately assume fire by introduction, etc (firing by rank or file, as Daniel Staberg previously stated). Frankly, I have difficulty with even this concept given the numbers stated and in the sense of an orderly rotation, but I'll defer the point lacking resource. What I don't imagine is salvo fire, or the firing of two or more ranks simultaneously.

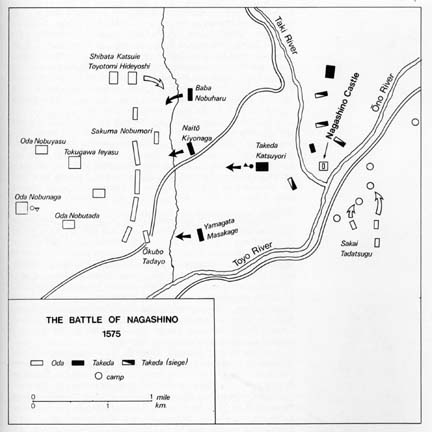

My curiosity in the topic stems from an interest in much later British formations and a burgeoning interest in the Thirty Years War, and I claim little to no interest in feudal Japan beyond the common. In following Daniel's example of a google search, I, too, looked up variations of Nagashino, Nagashino&volley&fire, Nagashino&salvo, Nagashino&arquebus, etc. And while it's true that there are scores of sites offering up info, the dozen or so I viewed all traced their info back to Osprey and Stephen Turnbull. Well, Turnbull does, indeed, describe Nobunaga's arquebusiers firing in volley. We know what constitutes a volley in the artillery sense. Yet, some of the sites I viewed do go on to directly compare (either outright or by date and inference) Nobunaga's accomplishmernts at Nagashino to the refinements in salvo fire of Gustavus Adolphus...though always refering to those later accomplishments in terms of volley fire. At least one site extended the courtesy of explaining the order of Nobunaga's forces firing rank by rank, only to then term it an innovation decades ahead of anything to be found in Europe.

As Daniel Staberg suggests, isn't it most likely that the disagreement here is simply a basic misunderstanding in regards to "volley" vs "salvo" which has been promulgated?

Michael

| Quote: |

| When I read the above "organized three-rank volleys", I immediately assume fire by introduction, etc (firing by rank or file, as Daniel Staberg previously stated). Frankly, I have difficulty with even this concept given the numbers stated and in the sense of an orderly rotation, but I'll defer the point lacking resource. What I don't imagine is salvo fire, or the firing of two or more ranks simultaneously. |

Mm. Some more research I've done on my own has turned up little evidence that Nobunaga's musketeers were using massed salvo fire at Nagashino, as I had previously understood, but that they were instead firing in countermarching volleys (pretty much the same as those described by Maurice of Nassau ten years later, though they may have been used in Europe before then) and that it was a more effective tactic for the situation. Also, Nobunaga's ashigaru were fighting in a three-rank formation and apparently keeping up rapid fire when contemporary European doctrine had musketeers in 6+ ranks, although they were in a static, well-defended position.

I have a hunch that the Japanese still developed and used salvo fire first (there are quite a few artistic depictions showing at least two ranks of teppo ashigaru ready to fire simultaneously, even in the stylized Japanese art of the period), but I can't exactly press the point at the moment for a severe lack of decent research material. Moreover, the teppo was at least as good, if not better, than contemporary European musketry - I've seen referenes to conical bullets used with them, and cartridge ammunition may have been invented and used widely in Japan first.

These articles by Stephen Turnbull, in particular, were highly informative as to both the tactical realities at Nagashino and the development of Japanese fortifications in the late Sengoku. http://www.ospreysamurai.com/castles_nagashino.htm

Last edited by Tyler Weaver on Mon 12 Sep, 2005 10:32 pm; edited 3 times in total

| Tyler Weaver wrote: |

| Moreover, the teppo was at least as good, if not better, than contemporary European musketry - I've seen referenes to conical bullets used with them, and cartridge ammunition may have been invented and used widely in Japan first. |

Cartridges made of paper may be proven to have been in service by Europeans by the middle of the 16th Century at the latest, and probably a few decades earlier, as patron boxes for use with pistols were in wide use prior to 1560. Paper was a fairly expensive commodity in Europe of course, thus cartridges were reserved for the rather elite Cavalry troops. As paper was somewhat more common in Japan, it wouldn't surprise me that this was looked into, but I had not heard of it's use for cartridges prior to this. Conical bullets, though experiemented with, don't work well with smoothbores (at least the types of conical bullets which were developed prior to around 1900). Rifles are another deal, but even at that, without a hollow base (not developed in the West until the second quarter of the 19th Century) it's a difficult bullet to use with a muzzle-loader. It would be interesting to see what the Japanese were managing to do with their experiments in this technology.

Cheers,

Gordon

So, it's not fire by salvo or Adolphus' refinement of mobility that is foreseen at Nagashino, but rather the initial gains in flexibility as demonstrated by the tactics first described by William and implemented by Maurice of Nassau against the Spanish which were realized by Nobunaga?

I see. I was originally going to reply with a "Gordon Frye said it better than I could, though anything is possible" sort of post, but your edit leaves me with a few more questions than the original post. I'm beginning my daily Nagashino--though we fight it with rubber bands and paper clips behind a bulwark of file cabinets--but I'll see if I can organize my questions and reply this afternoon.

Briefly, if we accept the three rank formation of three-thousand arquebus, have you considered that Nobunaga's tactics, given the terrain and numbers involved, might have had far more in common with those used by the enemy Maurice of Nassau faced? At least as far as rotation and the question of a fairly involved countermarch is concerned? Granted, the thousand man rank has me dubious for a variety of reasons. But then, there doesn't seem to be any hard data either way in this instance.

Michael

I see. I was originally going to reply with a "Gordon Frye said it better than I could, though anything is possible" sort of post, but your edit leaves me with a few more questions than the original post. I'm beginning my daily Nagashino--though we fight it with rubber bands and paper clips behind a bulwark of file cabinets--but I'll see if I can organize my questions and reply this afternoon.

Briefly, if we accept the three rank formation of three-thousand arquebus, have you considered that Nobunaga's tactics, given the terrain and numbers involved, might have had far more in common with those used by the enemy Maurice of Nassau faced? At least as far as rotation and the question of a fairly involved countermarch is concerned? Granted, the thousand man rank has me dubious for a variety of reasons. But then, there doesn't seem to be any hard data either way in this instance.

Michael

The counter-march doesn't have a lot of advantages and is in some ways riskier since it involves the musketeers moving in the space between the files. (Btw the Polish movie "Potop" aka "The Deluge" shows this very well in the final battle scene) A unit equipped with matchlock firearms has to maintain distances due to the risks involved in handling loose powder and lit matches. One of the major advantages of the firelock/flintlock was that it allowed a much tigther formation which resulted in more firepower for each yard of frontage.

The "normal" way prior to the introduction of the counter-march and the fire by division was to have the rotating ranks move back outside the formed ranks since this caused less disorder and was safer. The most important Dutch(?) innovation was firing by division, a units musketeers was divided into sub--units "divisions" of 3 to 8 files each and there was a space of 2-3 meters between each division. This meant that once a rank had fired it could move to the rear using this space http://www.geocities.com/ao1617/TactiqueUk.html#P56

The depth of European formations were only partly dictated by the rate of fire of the arquebus and musket, more important was the need for a unit which could operate on a battlefield were enemy cavalry would often have penetrated into the flank and rear of each sides army. The deep formations ensured that a cavalry unit appearing suddenly on one flank was faced with a fairly wide and well defended frontage rather than the narrow and vulnerable flanks of the later linear formations.

So the depth was to large degree determined by the depth in which the units pikes were formed. The shot units which formed up and operated more independently (the mangas or haufen) adopted thinner formations as needed.

When defending obstacles even thinner formations could and would be used to provide coverage of the entire length of the front. At La Bicocca (1522) the Spanish and Landsknecht arquebusiers formed up 4 ranks deep in order to man the the entrenchment and this was by no means an unique formation, similar formations can be found at Cerignola 1503 and even at Murten 1476. Seen from the european perspective Nagashino was nothing unusual or new.

Even if one accepts the pictorial japanese sources as evidence of multi-rank salvo fire it was nothing remarkable or new. That kind of "simple" salvo fire had been used in Europe from time to time since the early 16th Century. It is certainly not the equivalent of the Swedish style salvo fire introduced by Gustavus.

Cartridge ammunition doesn't really come in to it's own before you have soldiers armed with flintlock muskets equipped steel ramrods. The matchlock and the wood ramrod is a far greater hindrance to speedy (and proper) reloading than the way you carry your ball and powder once you have bandoliers and/or proper powder flasks. Rapid fire is somewhat overrated, once you get past a certain point it adversely affects unit control, accuracy and effectiveness.

Turnbull has one major problem, his knowledge of European warfare is limited, in a few instaces even poor compared to his knowledge on Eastern Subjects of the same period.

The speed and skill with which the Japanese were able to adopt and integrate firearms in their warfare is impressive in it's own right and IMHO there is no need to invent a supposed superiority that simply didn't exist.

Regards

Daniel

The "normal" way prior to the introduction of the counter-march and the fire by division was to have the rotating ranks move back outside the formed ranks since this caused less disorder and was safer. The most important Dutch(?) innovation was firing by division, a units musketeers was divided into sub--units "divisions" of 3 to 8 files each and there was a space of 2-3 meters between each division. This meant that once a rank had fired it could move to the rear using this space http://www.geocities.com/ao1617/TactiqueUk.html#P56

The depth of European formations were only partly dictated by the rate of fire of the arquebus and musket, more important was the need for a unit which could operate on a battlefield were enemy cavalry would often have penetrated into the flank and rear of each sides army. The deep formations ensured that a cavalry unit appearing suddenly on one flank was faced with a fairly wide and well defended frontage rather than the narrow and vulnerable flanks of the later linear formations.

So the depth was to large degree determined by the depth in which the units pikes were formed. The shot units which formed up and operated more independently (the mangas or haufen) adopted thinner formations as needed.

When defending obstacles even thinner formations could and would be used to provide coverage of the entire length of the front. At La Bicocca (1522) the Spanish and Landsknecht arquebusiers formed up 4 ranks deep in order to man the the entrenchment and this was by no means an unique formation, similar formations can be found at Cerignola 1503 and even at Murten 1476. Seen from the european perspective Nagashino was nothing unusual or new.

Even if one accepts the pictorial japanese sources as evidence of multi-rank salvo fire it was nothing remarkable or new. That kind of "simple" salvo fire had been used in Europe from time to time since the early 16th Century. It is certainly not the equivalent of the Swedish style salvo fire introduced by Gustavus.

Cartridge ammunition doesn't really come in to it's own before you have soldiers armed with flintlock muskets equipped steel ramrods. The matchlock and the wood ramrod is a far greater hindrance to speedy (and proper) reloading than the way you carry your ball and powder once you have bandoliers and/or proper powder flasks. Rapid fire is somewhat overrated, once you get past a certain point it adversely affects unit control, accuracy and effectiveness.

Turnbull has one major problem, his knowledge of European warfare is limited, in a few instaces even poor compared to his knowledge on Eastern Subjects of the same period.

The speed and skill with which the Japanese were able to adopt and integrate firearms in their warfare is impressive in it's own right and IMHO there is no need to invent a supposed superiority that simply didn't exist.

Regards

Daniel

"But for our current purpose, Tyler, I believe Daniel Staberg has already addressed this issue...both as it pertains to Gustavus Adolphus' adaptations in response to a specific threat and to the history of European shot formation in general."

As corrected.

My apology,

Michael

As corrected.

My apology,

Michael

| Tyler Weaver wrote: |

| Mm. Some more research I've done on my own has turned up little evidence that Nobunaga's musketeers were using massed salvo fire at Nagashino, as I had previously understood, but that they were instead firing in countermarching volleys (pretty much the same as those described by Maurice of Nassau ten years later, though they may have been used in Europe before then) and that it was a more effective tactic for the situation. Also, Nobunaga's ashigaru were fighting in a three-rank formation and apparently keeping up rapid fire when contemporary European doctrine had musketeers in 6+ ranks, although they were in a static, well-defended position. |

No. Just, no. You're vamping again, Tyler.

You really can't do anything else if the goal is to still support your thesis of prior development at Nagashino or with the Ikko-Ikki or anything else. The truth is that, beyond the generally given idea of three ranks, there is no hard fact which I've been able to determine regarding Nagashino and the order of Oda shot. Oh, I realize what a lot of internet sites say about the matter--wargame sites, this site, the Osprey site (though it changes from one Turnbull promo page and book to another), any number of sites, in fact--but the idea that something is often repeated simply doesn't, in and of itself, make it credible. Nor, quite frankly, does a desire for it to be so lend it any more credence.

What we can say with certainty is that Oda Nabunaga's goal was to break the cohesion of the Takeda cavalry and foot with his arquebus. To that end, the shot was necessarily placed in the vanguard of the Oda defenses. The exact relation of the shot is variously given as either forming directly behind the palisade or among the van proper of the Oda forces some fifty meters behind the roughly staggered and gapped palisade (Turnbull offers gaps for the purpose of counterattack every fifty yards). Now, in at least one account, the Oda line stretches for more than a mile. It was certainly a relatively long front, by any account.

The "palisade" itself begs the question of an accurate description since it is variously described as heaped earth surmounted with stakes; a bamboo and stretched net breastwork of some sort; a hasty fence of lashed wood and bamboo (Turnbull); or outward facing stakes of the more familiar variety with nothing more than the slowing and dividing of the Takeda horse as its goal (Turnbull). The height the palisade is either a disturbingly vague "high" or "just high enough to prevent a horse from jumping over"; while the supporting pike and archery is either mixed among the arquebus (Turnbull) or its disposition is simply never related (Turnbull).

At any rate, the combined Oda Nabunaga and Tokugawa forces are comprised of 38,000 men and have claimed their own ground and constructed a makeshift palisade overnight. The position is a good one. Since Takeda reinforcement isn't yet an issue, and seeing as how the Oda forces are not only entrenched but also enjoy a comfortable numerical superiority, the only possible concern is Takeda horse. Whatever the case, the Takeda obviously believed the Oda forces had fairly well dominated position. We can say this comfortably because rather than risk exposing their flank, the Takeda prove willing to oblige Oda forces by charging--over broken terrain and muddy ground--a palisaded barrier manned outright by more than three times their number.

In doing so, the Takeda cavalry first gives up preparation upon leaving the woodline to the tune of some 200 meters. And if the distance from the Oda lines to the woodline is only 200 meters and not the possible 400 mentioned, then It's still 100 meters from the initial woodline break to the supposed "high" banks of the Rengogawa. From here on, at least, the Takeda forces are exposed to Oda shot (the Oda aren't hunting, this is massed shot). Managing the far bank and cresting the near bank, it is still given as another 50 meters to the palisade.

The Takeda horse and foot (9,000 men with a 3,000 reserve by most all accounts) are usually portrayed as being divided into three groups attacking across the Rengogawa and along the Oda line (Turnbull, in at least one account, implies something more concentrated by vaguely describing the attack as wave after wave, though the waves may just as clearly be understood as individual regroupment after a volley). This makes sense to me, from the standpoint of attempting to expose a weakness in what little exists of the Oda flanks while seeking to forestall and protect against some sort of pincer movement. But, whatever the case, the goal of the Oda shot, breaking the cohesion of a "charge" of Takeda horse and foot from a position of defense, is well served by simple line formations as they would best allow for maximum contact with the opposing Takeda. It even possesses the added allure of being familiar to the Yumi rather than something radically different. You can form the lined "ranks" however you like with regard to volley. You can assume a more staggered echelon-like formation along the palisade; employ an 'every third man scenario; etc. In some accounts three commanders are given for the three ranks of shot. In others, the number is seven; though this may well reflect the three commanders and whatever passes for captains and sergeants in the Oda forces. The entire point is that no one seems able to say for certain one way or another. But, the line formation will serve the Oda forces admirably, still be groundbreaking in Japanese history for what it does undeniably accomplish, and not infer something which is nowhere in evidence.

And, at that, many of the Takeda made it through to engage the Oda lines. Remember, Tyler, in no account does the arquebus of the Oda and Tokugawa forces serve to settle the matter (well, in two of Turnbull's accounts it may be inferred, but...) in and of its' employment. On the contrary, the battle is almost universally said to have lasted from dawn to late afternoon with vicious hand-to-hand fighting being engaged early on and culminating in the retreat of the Takeda and an endgame pursuit by the Oda and Tokugawa forces.

Again, there is simply no reason beyond Turnbull's and others' sometime allusions to the methods of the Oda shot at Nagashino as bearing resemblance to the European countermarch to actually assume a European countermarch, Spanish or otherwise. A clear and uncontradicted description of the actual deployment is certainly nowhere to be found. Such a countermarch formation is far from necessary to gain the outcome as known, and actually poses the question of a weakened front line on the part of the Oda forces and exactly why the vaunted Takeda horse and foot would choose to attack in the teeth of such a shot formation when, assuming your countermarch of three thousand by three ranks, there were more vulnerable points of attack along the line. Nor is there any evidence that I can see of the inclusion of such tactics as the formed countermarch into later battles of feudal Japanese history, though the defensive earthworks tactics of Nagashino and simply line formation most certainly do see use in a movement towards even greater defensive postures.

And, once again, Turnbull himself is FAR from consistent in his descriptions of the Oda shot tactics.

Case in point? Why your very own link.

http://www.ospreysamurai.com/castles_nagashino.htm

Now, Tyler, while I appreciated the inclusion of a possible reference for your current assertion that a countermarch was employed by the Oda arquebus, I have to ask if you actually read what Turnbull offered in this particular account of the battle? I mean, like the fourth sentence?

Don't sweat it, though. I own Turnbull's The Book of the Samurai and Samurai Warfare and after reading some of his other writings on the topic of Nagashino, I feel more than confident in saying that Turnbull, himself, isn't sure about just what went down.

| Tyler Weaver wrote: |

| I have a hunch that the Japanese still developed and used salvo fire first (there are quite a few artistic depictions showing at least two ranks of teppo ashigaru ready to fire simultaneously, even in the stylized Japanese art of the period), but I can't exactly press the point at the moment for a severe lack of decent research material . |

Well, I can certainly understand the lack of reliable research material in this regard. But for our current purpose, Tyler, I believe Daniel Staberg has already addressed this issue...both as it pertains to Gustavus Adolphus' adaptations in response to a specific threat and to the history of European shot formation in general.

| Tyler Weaver wrote: |

| Moreover, the teppo was at least as good, if not better, than contemporary European musketry - I've seen referenes to conical bullets used with them, and cartridge ammunition may have been invented and used widely in Japan first. |

And Gordon Frye, a more knowledgable and certainly more patient gentleman than I, has already addressed these issues.

Michael

This topic has been promoted into a Spotlight Topic.

Hello everyone!

Tyler Weaver wrote

Spears had been widely used in warfare (both by cavalry and infantry) in Japan since the Onin Wars of the previous century, and almost certainly since well before that - possibly as far back as the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.

Actually, in all my books for Medieval Japan, this thing is described little different. The different types of yari were widely used by infantry, but not so wide by the cavalry. In fact, this so typical for Europe "lance cavalry charge" had been never adopted in Japan. The high rank samurais (those fighting on the horse-back) had always preferred to charge the enemy with bows and arrows, and swords at least to the end of Mongol invasion. The low ranks (those on foot) had charge (in order of use of weapons) first with bows and arrows, second with yari and at the end - with the swords. Of course we must consider that this had been a recommanded (desirable), but not mandatory order.

Boris

Tyler Weaver wrote

Spears had been widely used in warfare (both by cavalry and infantry) in Japan since the Onin Wars of the previous century, and almost certainly since well before that - possibly as far back as the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.

Actually, in all my books for Medieval Japan, this thing is described little different. The different types of yari were widely used by infantry, but not so wide by the cavalry. In fact, this so typical for Europe "lance cavalry charge" had been never adopted in Japan. The high rank samurais (those fighting on the horse-back) had always preferred to charge the enemy with bows and arrows, and swords at least to the end of Mongol invasion. The low ranks (those on foot) had charge (in order of use of weapons) first with bows and arrows, second with yari and at the end - with the swords. Of course we must consider that this had been a recommanded (desirable), but not mandatory order.

Boris

Before this gets too ascerbic, I was hoping someone could explain to me what Gustavus did, exactly, and how musket/harquebus formations worked before his innovation of salvo fire.

To put it more simply, what is salvo fire, what is fire-by-rank, and how do they compare? And, considering that this appears to be a slightly different subject, what is countermarching?

This is a very interesting conversation, I just wish I knew more than half of what was going on!

To put it more simply, what is salvo fire, what is fire-by-rank, and how do they compare? And, considering that this appears to be a slightly different subject, what is countermarching?

This is a very interesting conversation, I just wish I knew more than half of what was going on!

Hello guys!

I am sending picture of (another???) Tokugawa's "Namban Gusoku" armour, which is a modern replica. It looks similar to that posted by David in the begining of this topic. What do you think, are they the same, or are different armours?

I have a black-and-white picture of the original Tokugawa's "Namban Gusoku" in one of my books in Bulgaria (now I am in Slovakia for a short period of time). When I return home in begining of December, I will check this.

Regards!

Boris

Attachment: 32.44 KB

Attachment: 32.44 KB

I am sending picture of (another???) Tokugawa's "Namban Gusoku" armour, which is a modern replica. It looks similar to that posted by David in the begining of this topic. What do you think, are they the same, or are different armours?

I have a black-and-white picture of the original Tokugawa's "Namban Gusoku" in one of my books in Bulgaria (now I am in Slovakia for a short period of time). When I return home in begining of December, I will check this.

Regards!

Boris

Hello, guys!

Sorry that I misled you. I haven't a picture of Tokugawa's namban-do, I have just its schematic. I'm sending it.

Sorry again

Happy New Year! Cheers!

Regards!

Boris

Attachment: 98.3 KB

Attachment: 98.3 KB

[ Download ]

Sorry that I misled you. I haven't a picture of Tokugawa's namban-do, I have just its schematic. I'm sending it.

Sorry again

Happy New Year! Cheers!

Regards!

Boris

[ Download ]

Page 2 of 2

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum