https://artofswordmaking.com/gallery/stella-aurea-ii-14thc

I bought this sword a few years ago. It was a second hand purchase. The sword was advertised as sharp from the maker, yet it was not. The previous owner had sharpened the edges on a WorkSharp, which means that my review is not a review of the sword as it came from the maker. The sharpening was skillfully done and only affected a small part of the edge. It must be, nonetheless, noted.

In this review, I'm going to focus on the sword and my impressions of it. It is already very long, and I'm going to exclude any historical musings, descriptions and examples. myArmoury has a rich reservoir of articles and wonderful forum posts on typology and many other historical topics.

First impressions

When I first saw this sword on Maciej's website, I immediately wanted to have it. It looks so good in pictures. From the colour combination of the handle and the pommel, to the shape of the blade, it is just a very pretty sword. My favourite part of it is the guard, which tapers in both dimensions away from the centre. The sword looks simple, but has a certain regal feeling about it when you look at it. It is probably one of my favourite swords that Maciej has made, based on aesthetics only.

Fit and finish

Fit is very good and so is the finish. This sword is properly constructed and has an aura of solid craftsmanship and a hand-made feel, as it should. The blade has a lower grit polish, and it is possible to feel its roughness with a fingernail. It has, as the previous owner commented, an organic look when compared to a higher grit satin finish. Yet is is simply a result of a lower grit polish, possibly with some remains of a filework from the previous stages of sword manufacture. The guard is polished to a higher grit, perfectly adequate. The grip has three risers in the middle which give it a unique look. I also like the combined look of the maroon leather wrap and the brass pommel with a coin inside, which add a level of refinement to the sword.

Pommel

The pommel is shaped well. It is round and does not taper on the side. It looks bigger and heavier than other pommels I have seen on single handed swords. I cannot measure its weight though. The custom coin inside is made from a different metal and is very securely attached. The edges of the pommel are chamfered just a little bit, but I consider them too sharp. Handling the sword and cutting with it resulted in some abrasions first and then in my skin being cut on the outer part of the palm. After some time, patina started to develop on the pommel. I imagine it could be easily cleaned with some metal polish.

Handle

The handle is pretty. The leather grip is well done and has stayed in place without issues. There are five risers on the handle, two of them close to the guard and pommel, and three in the middle, with a special decorated riser in between the other two. The cord imprint on the leather was well done but has started to become less pronounced after some use. While the three risers in the middle look good, comfort wise they are a bit of a nuisance. They are too wide to simply fit in between your middle and ring fingers and get in the way a little when using the sword and changing grips. The shape of the handle is comfortable otherwise, at least in a bare hand. I imagine it might be too big to provide good feedback on blade alignment in a gloved hand, but I have not tested it on any targets this way. The handle is bigger than on the Albions I have held. This is neither a positive nor a negative, simply a matter of preference.

Guard

The guard is my favourite part of this sword. It is moderately thick in the middle, where it has an interesting swell, and then slowly tapers towards the tips. This taper is not linear and there are no straight lines on the guard at all. I think this is the reason why it looks so good. It cannot be fully appreciated from the pictures, but when you have the sword in hand, it shows. The guard is like a great sculpture - there is no more material left to remove in it.

Blade

As my favourite sword reviewer says, it is now time to talk about the pointy, pointy, stabby part. The blade is a cross between Oakeshott's type XV and XVI. It is straight and has no visible ripples. It starts quite wide and has a non-linear taper towards the tip. The profile taper looks hollow at first, as the wide shoulders of the blade get narrower, and then starts to look a tiny bit convex as it keeps tapering towards the tip. It is not simply a narrow triangle, the edges waver just the tiniest bit for this to be noticeable from the profile. I think this further adds to the handmade aesthetic of the sword. After the fuller, the grind looks to have a diamond cross section, but it is not very pronounced and in reality a cross between a diamond and a very thick convex cross section. The distal taper results in the sword having some unusual properties. It tapers from the base till the end of the fuller, where it again gets almost as thick as at the base. As a consequence the area just before the fuller ends is where the sword bends the most. From after the fuller, sword starts tapering again and gets very thin in the last 7cm before the tip. The tip can be easily bent with two fingers and does not inspire confidence.

Handling and performance

It is now time to talk about swords performance. I'm going to focus on two main areas - edge grind and handling.

Let's begin with handling. Based on looks, one would expect this to be a sword which primary function is thrusting, while cutting would play a secondary role. The problem is, the tip control of this sword is the worst of around 20 single-handed swords I have handled so far. Even my iron bar 1.5kg 'buhurt' type blunt has a better tip control.

When you point this sword at your target, the tip wanders when you extend the hand, and it is considerably more difficult to hit a small target compared to my other swords. I can only speculate why that is. It might be that the tip is too thin and too light, while the pommel is too heavy. Maybe it is a close point of balance connected with a pretty long blade. I really cannot tell. One can still use the sword to thrust of course, and it is still a dangerous weapon as long as the pointy end goes in the other guy ;)

Cutting wise, because of the heavy pommel and a close point of balance, it is easy to accelerate the tip. The problem is, there is not enough mass past the point of percussion to deal any considerable damage, even to a person wearing thick cotton clothing. The area around and past the CoP is also not ground for cutting. I tested the sword, as is, still decently sharp after the previous owner sharpened it, on a cotton jacket, and the sword was not able to cut through it. Only draw cuts with a lot of force applied to the jacket against a rigid padding resulted in small incisions. The sword does not feel natural to cut with CoP and it feels better designed to accelerate the tip. It might be because of the heavy pommel. It is also the only sword I have, where it feels like the pommel works against your hand in the cut. It takes extra effort to stop the pommel when dry handling, as it wants to keep moving in the opposite direction than the blade. It is a peculiar sensation, like your weapon wants to work against you, and not with you. In fact, the whole time I had the sword, I couldn't stop but to feel that this sword needs a lighter pommel and some material removed from the main bevel past the fuller. It can still just about cut a water bottle when your edge alignment is good.

It is hard to say how to best grip this sword. With a typical grip, firm or loose, it feels all right but the tip control isn't good and the pommel can cut your hand. Thumb on the blade doesn't feel useful and the risers do not help when holding the sword this way.. I found another way to grip it, with your pinky around the pommel and your thumb on the side of the grip, saber style. This improves the tip control a bit and makes the cuts with CoP feel better. Unfortunately it also decreases the control you have of the sword. The owner of another Stella Aurea told me that he also likes this grip.

Edge grind

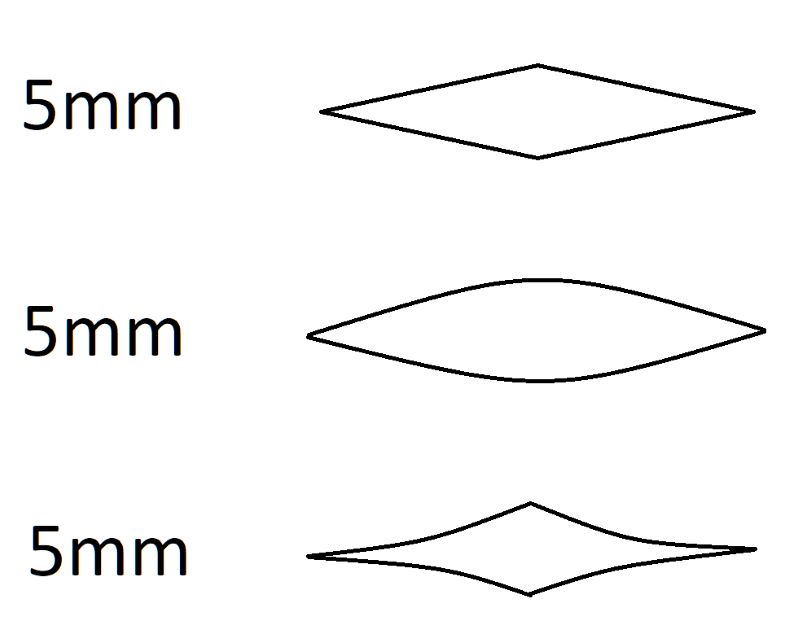

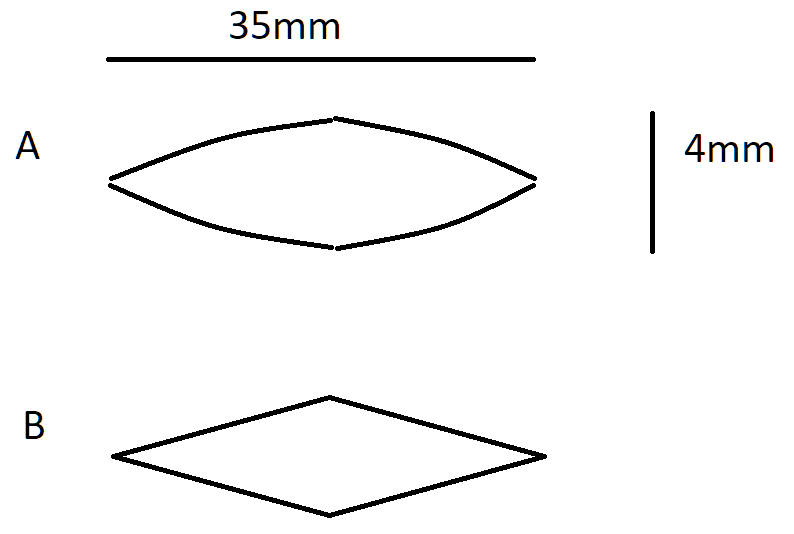

Now let me talk about the edge grind. I have attached a rough sketch that shows the cross-section around the point of percussion. The edge is thin and looks like I would expect a sword's edge to look like only in the part close to the grip. The trouble is that nobody uses that part to cut. Past the fuller and around the CoP the edge becomes extremely thick. I consider it thicker than an edge of a wood felling axe. I would expect things to be the other way around. To have a thicker, damage resistant grind (which would also help with mass distribution), in the half close to the grip, and more cutting oriented grind around the CoP and tip. Maciej has his own vision on sword's use. Here is one of his articles, which I personally find questionable and a little bit amusing. Responding to it fully would probably double the length of this review, so I'm not going to do that. Here is the link, so that every reader can form his own opinion:

https://artofswordmaking.com/gallery/sharpness-of-the-medieval-swords

I see a sword as a back-up weapon in times of danger or war, not as a main battlefield weapon. I also like knives and have a lot of experience with different types of grinds and edges. To me, a sword that cannot cut a single layer cotton jacket on a hard round pillow backing, which is supposed to roughly imitate a limb or a torso, is simply not a functional sword. Such a target is nothing compared to a gambeson. Most swords, especially arming swords are not very good as impact weapons. They need to cut. Some historical swords and sabres actually have edges thinner than a lot of modern utility knives. Maciej saying that his swords are not designed to cut paper, because they are designed to cut maille over gambeson without damage, like on historical battlefields, is just silly. None of us know how exactly were swords used in times of war 700 years ago. I, however, consider it likely that the physics behind cutting hasn't changed with time.

Back to Stella Aurea II - this sword would not do any cutting or impact damage to an opponent wearing maille or plate. The tip is also too thin to be considered usable in an armoured context. It feels like it would easily bend or snap after one misaligned thrust. It is clearly not a battlefield weapon. Is it a civilian duelling sword then? Its thick edge and its inability to cut a single layer of clothing would suggest otherwise. I consider it to be a very good looking sword, solidly constructed and pretty to look at. It just misses the mark in two areas important to me - handling and cutting performance.

One important area left to discuss is the thickness and distal taper. This sword is advertised to be 6mm thick at the base. Based on my electronic calipers it is between 4.5 - 4.8mm at base. The former value if squeezed tightly, the latter with a more relaxed measurement.

Blade length - 82.3cm

CoP - around 49cm

Distal taper (with relaxed measurements, subtract 0.3mm when pressing on the caliper's jaws):

0cm - 4.8mm

10cm - 4.3mm

20cm - 4mm

30cm - 4.5mm

40cm - 4.5mm

50cm - 4.3mm

60cm - 4mm

70cm - 3.3mm

80cm - 1.7mm

Summary

I have corresponded with the owner of another Stella Aurea and his experience related to his sword's thickness is the same. I have looked at many Maciej's swords on his website, read several reviews, and it feels to me that a lot of them share a similar trait - they are significantly thinner at base than advertised, do not distal taper much, and have heavy pommels to balance, no matter the type. I believe it would be better to do more balancing with distal taper and less with a pommel weight. My impression as an owner of Stella Aurea and an enthusiast of quality replicas is that Kopciuch also cuts some corners to increase his output and advertises it as a medieval aesthetic and authenticity. A good distal taper, nice polish and proper edges are very time consuming to do. But this is a purely personal opinion. On another note, I thought I was alone in these impressions until I saw that one of the sword youtubers published a video on the subject. Kane Shen has recently posted a video where he is very critical of Maciej's swords performance. Significantly more critical than me. He has a peculiar online persona but is very knowledgeable about swords and has a critical eye, which I value. His findings on Kopciuch's sword cutting performance agree with mine. Around 23.45:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Q9XH7FJOxY

Would I recommend Kopciuch's swords? It is not an easy question to answer. On the one hand they are well made and feel solid in hand. A lot of his swords and scabbards are also beautiful to look at. IIRC, I read on his website that Maciej graduated an arts high school, which would explain his eye for visual details. On the other hand, the one I had misses the mark on two most important sword qualities - handling and understanding of edge grind and cutting performance. I would consider buying another one of his swords in the future, but only after handling it in person.

I do not have many pictures and the sword is not longer in my possession. I will try to attach a few pics as a thank you to every reader who managed to get through this wall of text :)

Picture A is a rough illustration of the sword's cross section. Picture B is what it could be.