Specs – in inches

Overall Length – 17.25

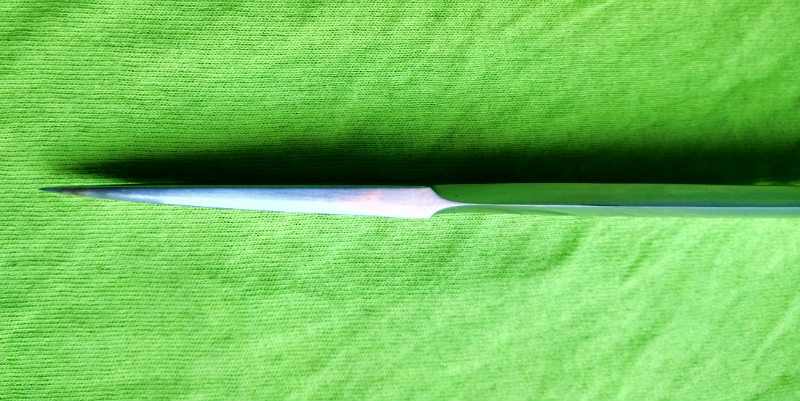

Blade Length – 12.25

Blade Width – 1.00 at guard

Grip Length – 4.00

POB – 1.25

Weight – 12.9 oz.

The blade shape is interesting. The dorsal side is wider and blunt. For most of its length it has an inverted V shape (to cut down on weight?) Near the tip it flattens to help reinforce that tip. The blade has almost a concave shape as it narrows down to the sharpened ventral edge. And of course, it has a very formidable point. This dagger type was made to fight an opponent in plate armor, to pierce its vulnerable areas (armpit, groin, visor, etc.) with a point strong enough to go through the mail and padding underneath. Wearing one at your side was a mark of high status. You will find rondel daggers as part of the armament on many 15th century effigies and brasses. Like I said at the top, this is a fairly inexpensive piece of high quality.