The first is from when he describes Pero as an exemplar of strength:

| Quote: |

| Moreover, he used to bend the strongest crossbows from the girdle |

The second comes when the King of Castile entrusts Pero with a privateering expedition against North African pirates in 1404

| Quote: |

| the best crossbowmen should be sought for, men well knowing the handling of their arms, good marksmen and trained to bend the arbalest from the girdle |

The translator, Joan Evans, helpfully provides an endnote to the first passage, which includes the original Castilian "Armaba muy fuertes ballestas à cinto". Evans considers this a reference to goat's foot levers, but to me it seems more likely to be a reference to a spanning belt. Drawing very strong arbalests, especially at the turn of the 15th century, with a belt hook would be quite a feat. I thought that belt spanning had been devalued to the point of obsolescence by the invention of the goat's foot lever, the wider proliferation of armour and the use of heavier armour, so that was a ding against my interpretation.

However, after examining some 15th century artworks, I found some corroborating evidence for my view. The belt spanning method, far from going by the wayside, seemed to be common even to the end of the century.

First the crossbowmen in Uccello's Battle of San Romano. Of those that you see spanning their weapons, they all seem to be using belts.

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

And second, Signorelli's Martyrdom of St. Sebastian. In addition to the pulley system that seems to be in use here, the middle crossbowman is also wearing a spanning belt.

[ Linked Image ]

Another detail I've observed in this painting is that the prod on the belt-and-pulley spanned arbalest is distinctly made of organic material (horn, wood, I don't know what), rather than the steel prods of the other two of which at one is spanned by goat's foot lever. Similar prods also feature on all the bows in the Uccello painting.

[ Linked Image ]

I'm not sure of the significance of this, but it seemed worthwhile to mention!

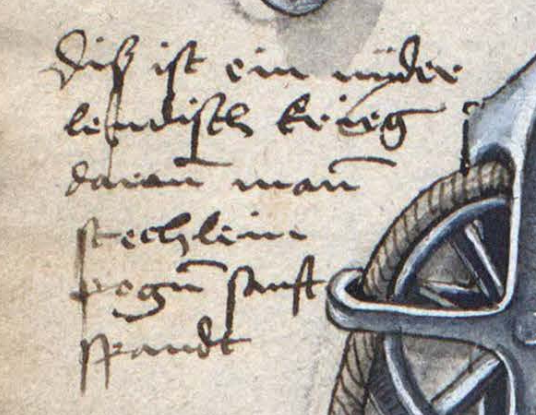

I've found a number of other artworks of which I don't know the exact provenance, but can post them later if desired.

If these prods had weaker draw weights than other types of crossbow, why do they see such frequent employment, even against heavily armoured foes? My best guess is that aiming for the face was a key tactic for fully-armoured opponents, and wounds to the limbs could be made against ones armored with only a breastplate or brigandine, and the psychological effect of arrow fire would still be valuable. However, these same tactics could be adopted by someone using a 200 lb crossbow, rather than the very strong examples preferred by Pero Niño. So it seems to me they must have some kind of effectiveness beyond what I can guess at.

If anyone can tell me why the "best crossbowmen" should be proficient in this method, or why it was preferred by Pero Niño, I would very much like to know.