Greetings,

long time lurker here, finally decided to register.

I searched the forum(and the internet in general) a bit and found no results for this topic so I decided to make a new thread about it.

Namely, what resulted in the creation and the popularity of flat top helmets during the time they were in use?

It is not as if various designs, both rounded and pointy top skull were unknown of before, the flat top was developed and used long after those were widespread and also alongside them.

Is there any argument for it apart from aesthetics?

Literally the only thing I found online as an argument is this image done by a random forum member at taleworlds;

http://i.imgur.com/0V4drZU.png

I find it very intriguing that men would choose a helmet design which pretty much guarantees that every downward blow will connect with his head and through his head...his neck.

Hello Mario,

Welcome to the community! Nice to see a fresh name from Croatia - I recently spent a couple months in your country and am smitten (my mother's family is from Hvar and Split). Where are you located particularly? As to your question...

Almost all evidence for the development of flat-topped helmets in the High Middle Ages coincides with the evolution of multi-plate helmets - including brims, visors and wrap-around protection. This advancement in crafting helmets from multiple plates implies that a simplification of the process of forming individual plates was probably good for production purposes. Having to fit a bunch of plates together with rivets adds a lot of time to the process of crafting a helmet, whereas in the past they had simply been hammered from single plates and made into conical or spherical forms.

As the 13th century progresses we notice a quick return of conical forms even with complex construction, and by the 14th century the flat top is almost entirely out of vogue even among the simplest helmet styles. This suggests that from a practical perspective the flat top was actually not a good invention - or it would have stuck around longer. So, my vote goes for production experimentation in the early phases of multi-plate construction as being one of the major reasons why we see the development of the flat top helmets.

Cheers!

-Gregory

Welcome to the community! Nice to see a fresh name from Croatia - I recently spent a couple months in your country and am smitten (my mother's family is from Hvar and Split). Where are you located particularly? As to your question...

Almost all evidence for the development of flat-topped helmets in the High Middle Ages coincides with the evolution of multi-plate helmets - including brims, visors and wrap-around protection. This advancement in crafting helmets from multiple plates implies that a simplification of the process of forming individual plates was probably good for production purposes. Having to fit a bunch of plates together with rivets adds a lot of time to the process of crafting a helmet, whereas in the past they had simply been hammered from single plates and made into conical or spherical forms.

As the 13th century progresses we notice a quick return of conical forms even with complex construction, and by the 14th century the flat top is almost entirely out of vogue even among the simplest helmet styles. This suggests that from a practical perspective the flat top was actually not a good invention - or it would have stuck around longer. So, my vote goes for production experimentation in the early phases of multi-plate construction as being one of the major reasons why we see the development of the flat top helmets.

Cheers!

-Gregory

| Gregory J. Liebau wrote: |

| Welcome to the community! |

Thank you :)

| Gregory J. Liebau wrote: |

| Where are you located particularly? |

In the general Zagreb area, I move around a bit between locations at the moment.

| Gregory J. Liebau wrote: |

|

Almost all evidence for the development of flat-topped helmets in the High Middle Ages coincides with the evolution of multi-plate helmets - including brims, visors and wrap-around protection for the lower head and neck (commonly referred to as 'kettle' and 'great' helmets). This advancement in crafting helmets from multiple plates implies that a simplification of the process of forming individual plates was probably good for production purposes. Having to fit a bunch of plates together with rivets adds a lot of time to the process of crafting a helmet, whereas in the past they had simply been hammered from single plates and made into conical or spherical forms. |

I see.

Though, how do you explain spangenhelms then?

They were widespread centuries earlier and also done with multiple plates constructed in a single shape, yet they were rounded or conical.

Seems very strange to me as I see it.

They went from segmented conical helmets to the single piece nasal helms and then switched from the rounded/conical/pointy skull top to the flat top as soon as face plates started pushing in.

Has it something to do with the desire protecting the entire face?

The first enclosed helms were flat topped from what I know.

The earliest helms with face guards appear in the last couple of decades of the 12th century, and seem to have conical or domed skulls, but no protection over the nape. Around 1200, the style seems to have evolved towards the flat top, and an extra plate is being added at the back of the neck by 1220. Alan Williams and David Edge strongly suggest the flat-top construction is largely due to the inability to make the necessary plates in heavy enough pieces (>0.5-1 kg) to allow anything other than a riveted construction until the early 14th century.

It could be that the men who wore these helms, mounted knights, thought the threat of a lance or spear strike from the front or below outweighed the risk of a sword strike from another mounted man.

Also keep in mind that there was almost always a second line of defense for the knightly class - the mail coif worn beneath the helm, and after c.1230 a cervelliere as well. Some helms with single-piece caps also have a reinforcing band riveted below the corner of the skull which must have added resistance to downward cuts at the corner (Linz, Madeln B). In others, the top cap is a riveted plate which would have given double thickness at the junction, so the weak area of the riveted join is at least two layers thick. By 1260 or 1275 the more rounded or conical "sugarloaf" style had become prominent, and even great helms eventually started to have a shaped upper plate (Pembridge, RA IV.600, Black Prince), though this might have been a change to cover the more pointed bascinets beneath.

| Quote: |

| I find it very intriguing that men would choose a helmet design which pretty much guarantees that every downward blow will connect with his head and through his head...his neck. |

It could be that the men who wore these helms, mounted knights, thought the threat of a lance or spear strike from the front or below outweighed the risk of a sword strike from another mounted man.

Also keep in mind that there was almost always a second line of defense for the knightly class - the mail coif worn beneath the helm, and after c.1230 a cervelliere as well. Some helms with single-piece caps also have a reinforcing band riveted below the corner of the skull which must have added resistance to downward cuts at the corner (Linz, Madeln B). In others, the top cap is a riveted plate which would have given double thickness at the junction, so the weak area of the riveted join is at least two layers thick. By 1260 or 1275 the more rounded or conical "sugarloaf" style had become prominent, and even great helms eventually started to have a shaped upper plate (Pembridge, RA IV.600, Black Prince), though this might have been a change to cover the more pointed bascinets beneath.

| Mart Shearer wrote: |

| Alan Williams and David Edge strongly suggest the flat-top construction is largely due to the inability to make the necessary plates in heavy enough pieces (>0.5-1 kg) to allow anything other than a riveted construction until the early 14th century. |

Alright, but why a flat top construction?

Nasal helms were constructed out of a single piece(+the nose guard), why could they not just expand upon it and rivet the new additions to a single piece rounded/conical skullcap?

| Mart Shearer wrote: |

| It could be that the men who wore these helms, mounted knights, thought the threat of a lance or spear strike from the front or below outweighed the risk of a sword strike from another mounted man. |

I also considered this, and, from what I can deduce, a flat top construction has that one advantage, which is that it is more protective from frontal strikes to the forehead and downward strikes to the forehead, since even if he helm dents/caves in, or the weapon penetrates, the front plate is more removed from the upper part of the wearers skull than a rounded/conical helmet, which follows the curvature of the head.

| Mart Shearer wrote: |

| Also keep in mind that there was almost always a second line of defense for the knightly class - the mail coif worn beneath the helm, and after c.1230 a cervelliere as well. Some helms with single-piece caps also have a reinforcing band riveted below the corner of the skull which must have added resistance to downward cuts at the corner (Linz, Madeln B). In others, the top cap is a riveted plate which would have given double thickness at the junction, so the weak area of the riveted join is at least two layers thick. By 1260 or 1275 the more rounded or conical "sugarloaf" style had become prominent, and even great helms eventually started to have a shaped upper plate (Pembridge, RA IV.600, Black Prince), though this might have been a change to cover the more pointed bascinets beneath. |

True, but that is also the case for later, rounded helms.

| Mario M. wrote: | ||||||

Alright, but why a flat top construction? Nasal helms were constructed out of a single piece(+the nose guard), why could they not just expand upon it and rivet the new additions to a single piece rounded/conical skullcap?

|

To remove the face and neck plates further from the head, a larger conical cap would be needed. A larger cap would require a larger starting piece of metal.

Of course there are a few transitional styles like this:

http://manuscriptminiatures.com/4809/11903/

We have good dimensions and weights for a number of flat-topped great helms, weights for cervellieres, and for a number of later bascinets when production of larger starting pieces of metal were available. Does anyone have dimensions or weights on the surviving conical helms?

I'm backtracking a bit from where the conversation is now...

but I strongly disagree with that linked drawing from the beginning of the thread. It attempts to represent an interaction between three-dimensional objects in only two dimensions, and thus it assumes incorrectly that all blows and weapon points are going to impact more or less perpendicular with the helmet surface. The person inside that helmet is going to be moving around, trying very hard to make sure that this doesn't happen, so most blows will be glancing. If a weapon of any sort strikes a glancing blow against the surface of a round or conical helm, it is much more likely to get deflected harmlessly than if it hits the comparatively well-defined edge of a flat-topped helm, which it is much more likely to dig into (and thus transmit the force much more efficiently to the wearer's head and neck, which will not be good for him. Anyway, cutting or shooting arrows through a helmet is not exactly easy or commonly done, to say the least - that is why helmets were used.

So I'm inclined to agree with those who say they were made that way due to some or other manufacturing limitations rather than for additional protection. A similar thing happened to the turrets of battle-tanks in WWII - initially the turrets were slab-sided because it was easy to assemble them out of flat plate armour that way. But as anti-tank guns improved and started punching through the nice flat vertical sides of the turrets, the manufacturers started to take the extra trouble to bevel and curve the sides of their tank turrets, because it gave them a chance of deflecting the incoming projectiles. (if I remember correctly, modern tank armour uses ceramic plates which are actually intended to shatter to harmlessly absorb the energy of projectiles, which is why modern tanks have gone back to slab-sided turrets).

Edit: the spacing argument also doesn't really work: you can achieve a better result (uniform spacing all round the skull) with a large domed or conical helm and the appropriate internal helmet suspension system.

but I strongly disagree with that linked drawing from the beginning of the thread. It attempts to represent an interaction between three-dimensional objects in only two dimensions, and thus it assumes incorrectly that all blows and weapon points are going to impact more or less perpendicular with the helmet surface. The person inside that helmet is going to be moving around, trying very hard to make sure that this doesn't happen, so most blows will be glancing. If a weapon of any sort strikes a glancing blow against the surface of a round or conical helm, it is much more likely to get deflected harmlessly than if it hits the comparatively well-defined edge of a flat-topped helm, which it is much more likely to dig into (and thus transmit the force much more efficiently to the wearer's head and neck, which will not be good for him. Anyway, cutting or shooting arrows through a helmet is not exactly easy or commonly done, to say the least - that is why helmets were used.

So I'm inclined to agree with those who say they were made that way due to some or other manufacturing limitations rather than for additional protection. A similar thing happened to the turrets of battle-tanks in WWII - initially the turrets were slab-sided because it was easy to assemble them out of flat plate armour that way. But as anti-tank guns improved and started punching through the nice flat vertical sides of the turrets, the manufacturers started to take the extra trouble to bevel and curve the sides of their tank turrets, because it gave them a chance of deflecting the incoming projectiles. (if I remember correctly, modern tank armour uses ceramic plates which are actually intended to shatter to harmlessly absorb the energy of projectiles, which is why modern tanks have gone back to slab-sided turrets).

Edit: the spacing argument also doesn't really work: you can achieve a better result (uniform spacing all round the skull) with a large domed or conical helm and the appropriate internal helmet suspension system.

Yeah, that first drawing is a little silly. The bottom line with any helmet or armor which people like to imagine all kinds of disadvantages for, is: Fine, don't wear it! The "default" is always *no* armor, not "complete perfect armor". If you really think you'd be better off bare-headed than wearing a flat-topped helmet, go for it. As Andrew points out, you can't assume a weapon is ever going to be at the right angle to get a square hit on any helmet--for all we know, they may have noticed that a flat top was generally at a good angle to deflect the major threats (such as a couched lance).

The shape of the crown is irrelevant to the shape or position of the face guard, since that would be attached to the rim, which was always a horizontal band fitting closely around the head. (Or fitting around whatever was on the head already!) You always want the face of the helmet close to your eyes in any case, to allow the best possible vision through the eyeholes.

The flat-topped helmet protected the head. It was made by men who had generations of expertise behind them, and was undoubtedly tough and effective.

These men also had plenty of experience in forging iron into whatever shape they wanted, so I have a little trouble with the whole assumption that they couldn't make it round or pointed, or were so crippled by some perceived inability to get a bigger piece of metal. They made the shape their clients wanted. If *we* can't handle the "why", that's our problem, not theirs!

These helmets were made one-off for nobility. There was no mass production to worry about, nor need to cut corners and save money or production time. That may have been a little more of a factor with the shops turning out spears and arrows for the masses of grunts, but not for anyone making anything for a knight.

That said, I don't have any problem with general idea that pointed and rounded helmets *do* offer better protection all around, and that this was eventually recognized. I'm just saying that we should not assume that the best-armored men in the world were constantly concerned with the DISadvantages of what they wore, and constantly obsessed over the physics of angles, velocities, impacts, joules, etc.

I *do* think that the concern with neck damage is way over-hyped. For a lance impact from a mounted man, sure, but the whole idea was NOT to get hit on the head with those! You were supposed to deflect a lance with your *shield*, or dodge it entirely. Getting hit in any wrong spot was called "losing". If you think of how many people suffer broken necks from being punched in the face, it really doesn't seem like the major concern. Really, I can't think of ANY battle helmets or helms that actually supported neck and could keep it from flexing. *Jousting* helms did that, yes, by completely sacrificing the mobility which is essential in combat.

Basically, it's a good helmet! Maybe not perfect from the viewpoint of modern physics, but it was way better than anything else at that time. It seems pretty clear to me that armor was never assumed to be perfect in the first place. If it worked for the guys wearing it, who are we to think ill of it?

Matthew

The shape of the crown is irrelevant to the shape or position of the face guard, since that would be attached to the rim, which was always a horizontal band fitting closely around the head. (Or fitting around whatever was on the head already!) You always want the face of the helmet close to your eyes in any case, to allow the best possible vision through the eyeholes.

The flat-topped helmet protected the head. It was made by men who had generations of expertise behind them, and was undoubtedly tough and effective.

These men also had plenty of experience in forging iron into whatever shape they wanted, so I have a little trouble with the whole assumption that they couldn't make it round or pointed, or were so crippled by some perceived inability to get a bigger piece of metal. They made the shape their clients wanted. If *we* can't handle the "why", that's our problem, not theirs!

These helmets were made one-off for nobility. There was no mass production to worry about, nor need to cut corners and save money or production time. That may have been a little more of a factor with the shops turning out spears and arrows for the masses of grunts, but not for anyone making anything for a knight.

That said, I don't have any problem with general idea that pointed and rounded helmets *do* offer better protection all around, and that this was eventually recognized. I'm just saying that we should not assume that the best-armored men in the world were constantly concerned with the DISadvantages of what they wore, and constantly obsessed over the physics of angles, velocities, impacts, joules, etc.

I *do* think that the concern with neck damage is way over-hyped. For a lance impact from a mounted man, sure, but the whole idea was NOT to get hit on the head with those! You were supposed to deflect a lance with your *shield*, or dodge it entirely. Getting hit in any wrong spot was called "losing". If you think of how many people suffer broken necks from being punched in the face, it really doesn't seem like the major concern. Really, I can't think of ANY battle helmets or helms that actually supported neck and could keep it from flexing. *Jousting* helms did that, yes, by completely sacrificing the mobility which is essential in combat.

Basically, it's a good helmet! Maybe not perfect from the viewpoint of modern physics, but it was way better than anything else at that time. It seems pretty clear to me that armor was never assumed to be perfect in the first place. If it worked for the guys wearing it, who are we to think ill of it?

Matthew

Mario,

As far as spangen helmets are concerned, I consider them technically alien by way of comparison with these high medieval forms we're discussing. The 'spangen' plates were very small and likely produced as one-offs for nobility. As far as the historical sources are concerned and what archaeology has gleaned, wearing a metal helmet of any type was reserved for the elite warrior class during the early Middle Ages.

However, as we come to the 12th-13th centuries there is ample evidence to suggest that throughout Western Europe the advancement of urban society and new role of royal authorities in raising armies for international conflicts, all contributed to a burgeoning arms industry. It was particularly notable in places such as Tuscany and northern Germany. Orders began to be placed by local and royal government officials, mercenary leaders and high nobility investing in their own protection, that would often amount to hundreds or thousands of pieces of armour meant to be handed out to servicemen ranging from urban levies to professional squadrons.

It is this particular phenomenon that correlates in time and space both to the development of the flat-topped helmets and new forms of multi-plate construction, that I had in mind when writing my initial post.

Great helms probably were, yes - but certainly not all of them. Many liege lords outfitted their young knights and squires for battle and tournament purposes even as early as the period in question. To suggest that each one of them went in to have a helm custom fitted to their head is unreasonable given the fact that we know good armorers were not located willy-nilly all over the place. Blacksmiths who could repair things were in plentiful supply, but no evidence survives to suggest that every castle or hamlet possessed a quality armorer or the facilities necessary to do such work!

You also ignore the fact that a majority of helmets made with flat tops were more likely to be the little brimless or kettle types, which were used by the masses in the large feudal levies of the period. Just look through the Maciejowski Bible for so many possible varients... These were surely made by industry such as that which I mention above, and virtually no level of customization would have been feasible during the production of these pieces.

-Gregory

As far as spangen helmets are concerned, I consider them technically alien by way of comparison with these high medieval forms we're discussing. The 'spangen' plates were very small and likely produced as one-offs for nobility. As far as the historical sources are concerned and what archaeology has gleaned, wearing a metal helmet of any type was reserved for the elite warrior class during the early Middle Ages.

However, as we come to the 12th-13th centuries there is ample evidence to suggest that throughout Western Europe the advancement of urban society and new role of royal authorities in raising armies for international conflicts, all contributed to a burgeoning arms industry. It was particularly notable in places such as Tuscany and northern Germany. Orders began to be placed by local and royal government officials, mercenary leaders and high nobility investing in their own protection, that would often amount to hundreds or thousands of pieces of armour meant to be handed out to servicemen ranging from urban levies to professional squadrons.

It is this particular phenomenon that correlates in time and space both to the development of the flat-topped helmets and new forms of multi-plate construction, that I had in mind when writing my initial post.

| Matthew Amt wrote: |

| These men also had plenty of experience in forging iron into whatever shape they wanted, so I have a little trouble with the whole assumption that they couldn't make it round or pointed, or were so crippled by some perceived inability to get a bigger piece of metal. They made the shape their clients wanted. If *we* can't handle the "why", that's our problem, not theirs!

These helmets were made one-off for nobility. There was no mass production to worry about, nor need to cut corners and save money or production time. That may have been a little more of a factor with the shops turning out spears and arrows for the masses of grunts, but not for anyone making anything for a knight. |

Great helms probably were, yes - but certainly not all of them. Many liege lords outfitted their young knights and squires for battle and tournament purposes even as early as the period in question. To suggest that each one of them went in to have a helm custom fitted to their head is unreasonable given the fact that we know good armorers were not located willy-nilly all over the place. Blacksmiths who could repair things were in plentiful supply, but no evidence survives to suggest that every castle or hamlet possessed a quality armorer or the facilities necessary to do such work!

You also ignore the fact that a majority of helmets made with flat tops were more likely to be the little brimless or kettle types, which were used by the masses in the large feudal levies of the period. Just look through the Maciejowski Bible for so many possible varients... These were surely made by industry such as that which I mention above, and virtually no level of customization would have been feasible during the production of these pieces.

-Gregory

| Matthew Amt wrote: |

| These men also had plenty of experience in forging iron into whatever shape they wanted, so I have a little trouble with the whole assumption that they couldn't make it round or pointed, or were so crippled by some perceived inability to get a bigger piece of metal.

These helmets were made one-off for nobility. There was no mass production to worry about, nor need to cut corners and save money or production time. That may have been a little more of a factor with the shops turning out spears and arrows for the masses of grunts, but not for anyone making anything for a knight. |

Yet Dr. Williams doesn't feel the 13th century bloomeries could turn out bigger pieces of metal.

| Dr. Alan Williams wrote: |

| The more sophisticated metallurgy of the 14th century provided

larger pieces of steel, and skilled metalworkers were able to take full advantage of that, so that the production of one-piece helmets becomes practicable because they are made of better metal. |

Do we really know great helms were all one-offs and not mass produced? Compare the Pembridge helm with RA IV.600.

[ Linked Image ]

| Dr. Nickolas Dupras wrote: |

| The Royal Armouries great helm is an excellent example of a helm for war, and one of

three ‘English’ great helms, along with the Pembridge helm in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the helm of Edward the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral. It is identical in construction to the Pembridge helm and so similar in details and form that it was initially thought to be a well-made fake |

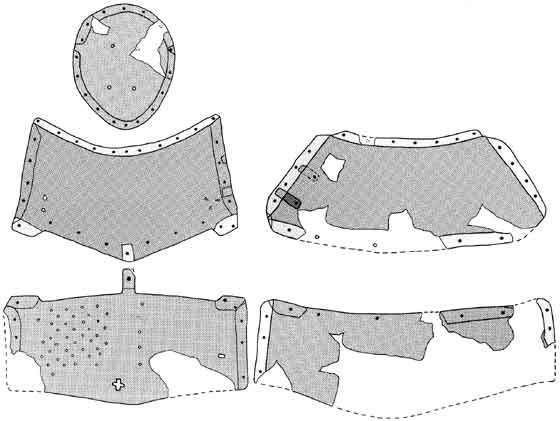

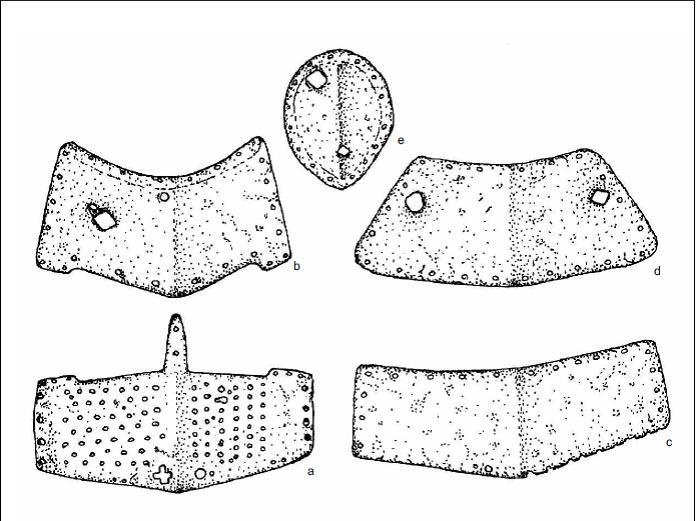

Compare the patterns for Madeln A and the Dalečín helms. Is it too hard to believe they aren't made from the same pattern?

Madeln A

Dalečín

Dr. Randall Storey's thesis contains a fine example of the numbers involved in such contracts, confirming Gregory's point.

Even subcontracting out, and presuming the majority of the 2853 helmets were cervellieres and kettle hats, some standardized production methods were almost certainly implemented. I feel fairly certain that manufacturing to a single pattern was likely employed by more than one shop. "Do one thing and do it well."

| Quote: |

| For example, in 1295 Phillip IV's emissary purchased at Bruges a hoard

of arms to equip a fleet .... The entire purchase included 1885 crossbows, 1254 lbs. of hemp for cords, 666,258 quarrels with 1691 quivers, 6309 shields, 2853 helmets, 4511 aketons, 751 pairs of gauntlets, 1374 gorgets, 5067 coats of plates, 13,495 lances, 1989 hatchets, 14,599 swords and daggers and 40 springalds,C. Gaier, (Paris,1973), p. 118.L'Industrie et le Commerce des Armes dans les Anciennes Principautés Belges du XIIIme à la fin du XVme Siècle |

Even subcontracting out, and presuming the majority of the 2853 helmets were cervellieres and kettle hats, some standardized production methods were almost certainly implemented. I feel fairly certain that manufacturing to a single pattern was likely employed by more than one shop. "Do one thing and do it well."

Can i add in a wee point about the early great helm design. Despite the many repro's beloved of reenactors out there which have the top plate on the outside of the upper section, I'm not convinced this is the common way to do it. Most surviving examples have the opposite and the oft cited King Louis bible, if studied closely, also shows that kind of design, where such is discernible.

Its certainly easier, and of course stronger, but apart from the Wells cathedral example, others and rather trickier to pin down. I keep meaning to get a table together to look at this but life/work/armour balance is a bit skewed at the moment!

Griff

Its certainly easier, and of course stronger, but apart from the Wells cathedral example, others and rather trickier to pin down. I keep meaning to get a table together to look at this but life/work/armour balance is a bit skewed at the moment!

Griff

The Dargen has the top plate over, though others have it beneath, or the entire upper half made of a single piece. Many are three plates instead of five.

| Gregory J. Liebau wrote: | ||

Great helms probably were, yes - but certainly not all of them. Many liege lords outfitted their young knights and squires for battle and tournament purposes even as early as the period in question. |

Those are nobles, aren't they? ;)

| Quote: |

| To suggest that each one of them went in to have a helm custom fitted to their head is unreasonable given the fact that we know good armorers were not located willy-nilly all over the place. Blacksmiths who could repair things were in plentiful supply, but no evidence survives to suggest that every castle or hamlet possessed a quality armorer or the facilities necessary to do such work! |

No, I don't maintain that every aristocratic piece of armor was carefully custom-fit to the client! But that liege isn't going to hand great helms out to young aristocrats with the common grunt's "too big or too small" method, either.

| Quote: |

| You also ignore the fact that a majority of helmets made with flat tops were more likely to be the little brimless or kettle types, which were used by the masses in the large feudal levies of the period. Just look through the Maciejowski Bible for so many possible varients... These were surely made by industry such as that which I mention above, and virtually no level of customization would have been feasible during the production of these pieces. |

True, I wasn't thinking about kettle hats and other low-end helmets, since the initial post had me thinking mainly of full-face great helms and such. Absolutely the armor industry was huge and productive. To me that still denies the idea that flat-topped helmets of any sort inherently gave significantly inferior protection. Or a lot more guys would have refused to wear them, wouldn't they? Even with smaller pieces of metal, there was nothing to prevent those helmets from having round or conical tops. A flat top was not some suicidal victory of fashion over function.

Thanks for those tidbits, Mart! It's something to think about. I certainly have no problem with armorers sticking rigidly to fashions or actual patterns in general, we see that all the time with Greek and Roman stuff for sure. And it's funny because especially with the Greek stuff there is a tendency to assume that every Corinthian helmet was custom-made for a specific buyer, while I argue that they did not all have to be custom-fit! So here I find myself arguing in the opposite direction, ha! Score one for human inconsistency, eh? I guess I have long envisioned an armor shop having a table full of cheap helmets at the market, for the local militia and mercenaries to try on and buy, in between large mass orders for a lord or town arsenal stocking up. It's a little harder to imagine a young knight browsing a similar table of great helms--maybe it's just my own preconceptions that see him going straight to the armorer (who may certainly have a few finished items for his lordship to try on), or even have the armorer come to him for measurements and discussion of options.

I'll just put my hands over my ears and tell everyone else to keep an open mind, ha! La la laaaa la la la laaaaa...

Matthew

| Matthew Amt wrote: |

| Yeah, that first drawing is a little silly. |

That was the point, I wanted to comically present just how little information I managed to find and how useless that little was :)

| Gregory J. Liebau wrote: |

| The 'spangen' plates were very small and likely produced as one-offs for nobility. |

Spangen plates were smaller, but so would the high medieval ones be if they used the exact same segmented construction for the skullcap only with added face protection.

What prevented them from doing so?

Using the exact same construction as used with spangenhelms if they were not able do craft it from a single piece?

Was the additional surface of the metal so much bigger that they could not simply expand the already present single piece skull that was widespread through helms like the nasal helm?

I also find the arguments for mass production stated by others here to be arguable, from what I see, flat tops are very often depicted as being worn by completely armored men, a solid chunk of them on horseback.

From the pictorial depictions I collected so far, I do not see how those men wearing them needed a price drop so desperately that the design was sacrificed to such an extent solely in favor of a lower cost.

| Gregory J. Liebau wrote: |

| Blacksmiths who could repair things were in plentiful supply, but no evidence survives to suggest that every castle or hamlet possessed a quality armorer or the facilities necessary to do such work! |

I was not aware that it was necessary at all for a smith to actually be near the future wearer constantly during the craft period of the item.

From my understanding, a simple set of measurements taken once(or a few times over the crafting period) will allow a smith to produce an item properly fitted for the wearer without ever seeing him again.

Of course, it is much better if the wearer is present on demand at all times, however, considering my friend ordered a helmet from Ukraine based on some scanned and sent squibbles on a paper and received a helmet a couple months later that fitted him like a glove, I would say that it is not exactly a requirement.

Am I mistaken or was ordering full suits of armor from foreign armories(e.g. Milan) not common and done by men who never even once traveled to the location?

Your first question is very broad. Military technology, tactics, developing urban society and arms industry all play factors into the reasons why small plates derived from spangen helmets were not utilized to create more advanced forms of helmet. The need may not have been pressing, the concept not yet imagined, etc. To transfer this mentality to the high Middle Ages implies that spangens were still popular as the industry came to prominence. They were not. One piece helmets were the norm in Western Europe throughout the 12th century up until the development of the more advanced forms. Iron bloomery and the armourer's art had already surpassed the need to use small plates on a regular basis.

However, the demand for further protection produced a need for additional plates beyond even what contemporary industrial capabilities may have been, so we see a reversion to multi-plate construction that is in fact not a direct evolution of the spangen helmet at all. It is an invention preceded by the larger plates already being favored for single-piece helmets.

As to fitting,

Armorers were not even so common as to be available in every town or perhaps many in between. Men did not travel for days on horseback simply to go get measurements taken for a helm that could be produced in three or four adequate sizes in an arms facility and purchased from a local merchant. Helmets during the 12th-13th centuries (when flat-tops were in vogue) were never so technically precise that a made-to-measure fit is necessary. Even today the mass-production in India (think Windlass or Deepeeka) churn out helmets in two or three sizes, one or the other of which is satisfactory for almost any head size.

It was not until the later centuries of the middle Ages (late 4th-16th) and the advent of advanced plate armament that men took care to take measurements and finance the work of specific artisan craftsmen. Even at that time we are aware that most armour made for all but the richest men might have been sold in merchant settings and had nothing to do with custom sizing.

Just because something might seem reasonable from our perspective does not mean that things occurred that way. It is easy to email an armourer across the world today and make sure that your helmet will fit decently. Yet there is virtually no evidence for helmets being custom fitted during the High Middle Ages. We have many inventories and orders suggesting that dozens or hundreds of helmets were being made at a time, and sold at standard prices, etc... Yet there is not a single scrap of evidence for a man during this period having his head measured for a helmet. If I'm wrong I'll be happily corrected, but after a decade of study such a detail has eluded me.

A nice example is a surviving tournament roll from Windsor in 1278. Roughly two dozen cuir helms were delivered in time for the event to be used in a bohort by some of the highest nobility in England. They were all assembled in the same shop under the same set of criteria, without a single mention of size. If the great Earls and Dukes of England were fine fighting in off-the-shelf helmets gifted at the time of an event, I think generally we can be safe to say that most people would be.

I'm sure that custom fitting occurred when the occasion allowed. Certainly many men-at-arms could take advantage of living close to or passing through a center of the arms industry. But there is nothing to facilitate any historical claim that this was a preoccupation or considered an important part of the process of finding a good helmet during the High Middle Ages, whether it would go on the head of a king or a peasant. Any thought of the sort is conjecture that we must be careful about espousing as historical.

-Gregory

However, the demand for further protection produced a need for additional plates beyond even what contemporary industrial capabilities may have been, so we see a reversion to multi-plate construction that is in fact not a direct evolution of the spangen helmet at all. It is an invention preceded by the larger plates already being favored for single-piece helmets.

As to fitting,

Armorers were not even so common as to be available in every town or perhaps many in between. Men did not travel for days on horseback simply to go get measurements taken for a helm that could be produced in three or four adequate sizes in an arms facility and purchased from a local merchant. Helmets during the 12th-13th centuries (when flat-tops were in vogue) were never so technically precise that a made-to-measure fit is necessary. Even today the mass-production in India (think Windlass or Deepeeka) churn out helmets in two or three sizes, one or the other of which is satisfactory for almost any head size.

It was not until the later centuries of the middle Ages (late 4th-16th) and the advent of advanced plate armament that men took care to take measurements and finance the work of specific artisan craftsmen. Even at that time we are aware that most armour made for all but the richest men might have been sold in merchant settings and had nothing to do with custom sizing.

Just because something might seem reasonable from our perspective does not mean that things occurred that way. It is easy to email an armourer across the world today and make sure that your helmet will fit decently. Yet there is virtually no evidence for helmets being custom fitted during the High Middle Ages. We have many inventories and orders suggesting that dozens or hundreds of helmets were being made at a time, and sold at standard prices, etc... Yet there is not a single scrap of evidence for a man during this period having his head measured for a helmet. If I'm wrong I'll be happily corrected, but after a decade of study such a detail has eluded me.

A nice example is a surviving tournament roll from Windsor in 1278. Roughly two dozen cuir helms were delivered in time for the event to be used in a bohort by some of the highest nobility in England. They were all assembled in the same shop under the same set of criteria, without a single mention of size. If the great Earls and Dukes of England were fine fighting in off-the-shelf helmets gifted at the time of an event, I think generally we can be safe to say that most people would be.

I'm sure that custom fitting occurred when the occasion allowed. Certainly many men-at-arms could take advantage of living close to or passing through a center of the arms industry. But there is nothing to facilitate any historical claim that this was a preoccupation or considered an important part of the process of finding a good helmet during the High Middle Ages, whether it would go on the head of a king or a peasant. Any thought of the sort is conjecture that we must be careful about espousing as historical.

-Gregory

Interesting discussion!

Just in my opinion, the flat-top helmet was popular 13th-14th centuries, when medium and large shields were still being used as a matter of course, and likely, the one attack to which the flat-top is weak, an overhead downward strike from a sword or pole weapon, is all but trivial to defend against with a sword and shield.

There simply weren't enough drawbacks to offset the advantage of ease of manufacture, until manufacturing made the distinction academic.

Just in my opinion, the flat-top helmet was popular 13th-14th centuries, when medium and large shields were still being used as a matter of course, and likely, the one attack to which the flat-top is weak, an overhead downward strike from a sword or pole weapon, is all but trivial to defend against with a sword and shield.

There simply weren't enough drawbacks to offset the advantage of ease of manufacture, until manufacturing made the distinction academic.

Since Gregory brought up the flat-topped kettle hats in the Maciejowski Bible (and they do appear in other 13th century sources), it's worth noting that kettle hats with rounded skulls continue to be made of spangen-construction. There's even one depiction of the older spangen- conical helms, so they were at least familiar with them, even if they were considered obsolete or foreign by that point in time. It's possible that spangen-construction was still used on the lower-class helmets because the material cost of smaller plates made it more economical to do so.

Attachment: 153.83 KB

Attachment: 153.83 KB

Morgan M.638, fo.9v

Attachment: 154.15 KB

Attachment: 154.15 KB

Morgan M.638, fo.10r

Attachment: 118.29 KB

Attachment: 118.29 KB

Morgan M.638, fo.22r

Morgan M.638, fo.9v

Morgan M.638, fo.10r

Morgan M.638, fo.22r

im also unconvinced by the 'they were used by mounted troops' line

since mounted troops also fought OTHER mounted troops and it was fairly inevitable that it was going to come to blows with sword axe and mace

to my mind whats confusing is why the flat topped design was invented at all either as a flat topped nasel helm/ cerveliere, or as later greathelms,

we also know that some of the transitional helmets were conical i.e just a conical nasel helmet with a faceplate riveted onto it... it feels like history could have easily skipped the entire 13th century and just gone straight from transitionals to sugarloaf helmets.

since mounted troops also fought OTHER mounted troops and it was fairly inevitable that it was going to come to blows with sword axe and mace

to my mind whats confusing is why the flat topped design was invented at all either as a flat topped nasel helm/ cerveliere, or as later greathelms,

we also know that some of the transitional helmets were conical i.e just a conical nasel helmet with a faceplate riveted onto it... it feels like history could have easily skipped the entire 13th century and just gone straight from transitionals to sugarloaf helmets.

| William P wrote: |

|

to my mind whats confusing is why the flat topped design was invented at all either as a flat topped nasel helm/ cerveliere, or as later greathelms, |

We don't get to see directly what's under the flat topped helmets My understanding is that the large 'jousting helmets' went over the top of a bascinet or skull-cap style under-helmet, which would have provided substantial protection against blows that any flat top was never designed to resist by itself. I assume the flat-top helmets were a class of the oversize jousting helmets & so were never worn alone but were the top layer of head protection over a bascinet. The primary role of the flat-tops would have been to add facial protection to bascinets at a time when bascinets lacked visors.

The industrial & economic aspects of armor production should not be forgotten. Flattop designs may have been the easiest products for apprentices to turn out in large numbers. They may not have been at the top of the shopping list of the wealthiest knights but they may have been exactly what a limited budget allowed.

Page 1 of 1

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum