While looking up more information on the subject, I was surprised to discover that Wikipedia mentions,"The earliest known depiction of a cross-hilt dagger is the so-called 'Guido Relief' inside the Grossmünster of Zürich (c. 1120)" (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dagger#Middle_Ages). Intrigued, I looked to see if I could find a photograph of this relief, and fortunately, the Bildarchiv foto Marburg has one. Those of you who have spent much time perusing David Nicolle's books might recognize this image, although for most everyone else, I imagine it will be new. Although I had seen it before, I believe that I had previously only seen a line drawing by Nicolle, and I had assumed the weapon was a sword. Contrary to what Wikipedia says, Foto Marburg dates the relief to circa 1160-1180 AD; however, this still places it well within the 12th century.

The question is, do you think the weapon shown is indeed a dagger, or is it really a sword? Given how clearly the disk pommels are represented on the other swords in the image, not to mention their crosses, it seems somewhat unlikely that it is a sword. Sadly, the image gives us little indication of the shape of the blade. If a dagger, is there a dark line in the blade because it has "three sharp edges" like the new weapons observed by William the Breton in his prose account of the Battle of Bouvines? (http://deremilitari.org/2014/03/the-battle-of-bouvines-1214/). Or should it be interpreted as a fuller?

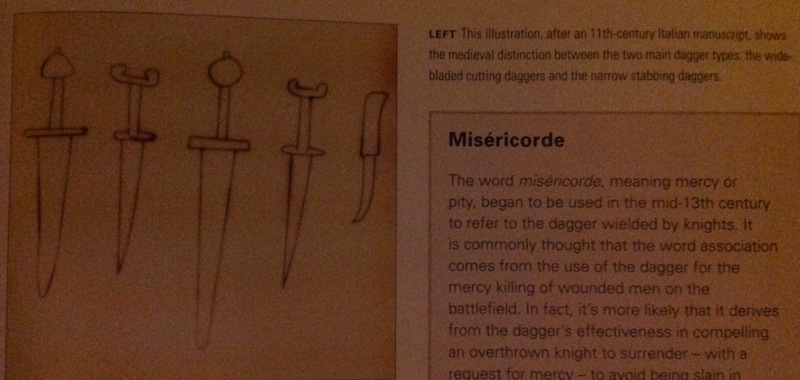

One thing that seems reasonably certain is that the shape of the guard and the grip is rather like those of the misericords Tod has for sale. See the attached image from his webpage (http://www.todsstuff.co.uk/knives-military/mi...knives.htm) below. But should the grip be interpreted as wood? Or should it be interpreted some other way?

An equally pertinent question we might ask is, assuming that the weapon is not a sword, is it even a military knife? Or is it just a civilian tool being used in a military context?

Although this image raises more questions that it answers, it may nevertheless serve as an invaluable piece of period evidence for pre-13th century military knives.

[ Download ]