A Fine and Rare Large Bohemian Pavise, circa 1400

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Of transversely curved rectangular shape with rounded corners, and formed of wood covered with gessoed canvas; the front painted with a red rampant lion bearing a writhen tie at the base of its tail, amid a pattern of brown volutes on a yellow ground, all within a red border; the rear painted black and fitted at its upper end with an iron ring bearing a leather suspension-loop, and at its lower end with an iron handle; and the lower edge fitted with two projecting iron spikes attached by rivets.

Overall height: 85 1/2 in Overall width: 30 1/2 in

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

The pavise--referred to in Italian and German documents as early as the first half of the 13th century--is thought to have taken its name from the North Italian city of Pavia. According to an anonymous chronicle of about 1330, 'The military renown of the Pavians is proclaimed all over Italy. After it are called large shields, rectangular at top and bottom, known as Papienses. It was perhaps through the influence of Italian mercenaries that the use of the pavise spread to other parts of Europe, most notably Bohemia where it was employed to impressive effect by the Hussite revolutionary armies of the late 14th and early 15th centuries. The bold heraldic design of the present example can be seen as a 'differenced' version of the arms of Bohemia, namely gules, a lion rampant or, occurring on a pavise of almost identical design that passed through the art market in 1994.

The pavise shown here is of notable size. Unlike most later examples of its kind, it has no prop at the rear to enable it to stand up by itself, and would therefore have had to be supported by a specialist pavise-bearer whose job it was to crouch down with it in front of the archer or crossbowman that he was assigned to protect. The use of the pavise in this manner is clearly seen in an illuminated manuscript of the third quarter of the 15th century, representing the taking of the town of Duras, in a copy of Froissart's Chronicles preserved in the Bibliotheque National, Paris (MS.2643). In Bohemia, the role of the pavise-bearer was recognized as an important one: by the second half of the 15th century, his pay had risen to twice that of the crossbowman.

The pavise under discussion can be compared in its form with a series deriving from the Town Hall of Erfurt in Saxony, of which the majority are now in the Anger-Museum of that town, one is in the Historisches Museum, Dresden, two more are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and another two were formerly in the Museum fur Deutsche Geschichte, Berlin. Several of these can be dated from the details of their heraldry to a period as early as 1385-87.

The Erfurt pavises, like the example under discussion, are fitted at their lower ends with a pair of projecting iron spikes that could be driven into the ground so as to better resist the onslaught of the enemy. A particular tactic of the Bohemians was to form a solid wall of pavises. This practice is recorded in a number of Landsknecht songs relating to the battle of Regensburg of 1504, as for example one that records how die Behmen hinder iren bafosen ... stunden vest wie die mauren (the Bohemians behind their pavises ... stood fast like the walls). The form of such a wall of pavises can be seen in one of the fine woodcuts illustrating the Weisskunig, prepared for the Emperor Maximilian I about 1516. In this semi-autobiographical work, the Emperor, in the guise of the 'Weisskunig', noted that as part of the education and training he received in his youth, he learnt various forms of battle and acquired a masterly command of battle 'with the Bohemian pavise on foot and the Hussar's targe on horseback', and later used this knowledge to good advantage against troops thus armed. The association of the pavise with Bohemia is further emphasised by four lines of verse appearing in the Emperor's Zeugbucherof 1519, which contrasts with the German manner of fighting, that of the Bohemians who carried 'large pavises':

Nicht allein auf die Teulschen art

is dieses paradeis bewart,

sonder nach Pehaimischem syt

tregt man uns gros pavesen rait.

This loosely translates as 'Not only in the German manner is this paradise preserved, but according to Bohemian custom do we carry large pavises with us'.

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Copyright © 2001 Peter Finer

A Fine Bohemian Pavise, circa 1480

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Of rectangular shape with rounded corners and a medial gutter of angular section narrowing slightly to a projecting 'beak' at the top, and formed of wood covered with gessoed canvas; the front painted on a white ground with red droplets falling from stylized blue clouds and yellow sun-rays at the top, to flowers of red, yellow and green at the bottom, and superimposed just below its centre with a large escutcheon charged with two rows of red piles or 'passion nails' on a white ground, all enclosed within a border of black, red and white bands; and the rear painted at its upper end, on a black background, with the red initials C and R separated by a white circle bearing in yellow gothic characters outlined in red the Christian device ihs, and fitted with a forked carrying-handle and two iron staples for the attachment of a suspension-loop.

Overall height: 50 1/4 in; Overall width: 21 in

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

The arms forming the central motif of this finely decorated pavise can be identified as those of the Bishopric of Olomouc (Olmutz) in Moravia, then a dominion of the kingdom of Hungary and Bohemia. The same arms are to be seen on three pavises formerly preserved in the Vienna Zeughaus, and now belonging to the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien. One of them (Inv. No. 126.150), is very like that shown here. Another (Inv. No. 126.158), is decorated at its centre with a representation of St George flanked on either side by the arms of Austria and Upper Hungary, and standing above the arms of the Bishopric of Olomouc paired with those of the Moravian family of Boskovic. The third (Inv. No. 126.123), is decorated at its centre with a Czech royal crown over the gothic letter b, almost certainly alluding, once again, to the Boskovic family. There can be little doubt that the pavises discussed above were made for the use of Taso of Boskovic, Prince Bishop of Olomouc from 1457 until his death in 1482. Allied with them is a further pavise in the Viennese collections (Inv. No. 126.114), which is decorated beneath the central figure of St George with the checkered eagle of Moravia, also used as the arms of the city of Olomouc. The pavises in question form part of a larger group evidently abandoned in Vienna by the forces of Matthias Corvinus (1443-90) who occupied the City in the period 1485-90. Some of them bear his personal arms and devices. In the Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, there is a pavise (Inv. No. 55.3264), which probably belonged originally to the group described above. Like the example shown here it is decorated with red droplets falling from the sky but overlain with the crowned gothic M of Matthias Corvinus.

Matthias Corvinus became King of Hungary and Bohemia in 1458, adding Moravia to his territories in 1478. Of the three military expeditions led by him against the Austrians in 1472, 1477 and 1480-85, only the last is likely to have involved the Moravian forces of the Bishop of Olomouc. It resulted in the conquest of the greater part of Austria, and the eventual occupation of Vienna from 1485 until the King's death in 1490. Of the pavises remaining in Vienna, that showing the arms of Upper Hungary in association with those of the Bishopric of Olomouc must have been made, or at the very least repainted, after 1478. On the other hand, the two pavises respectively bearing the personal arms and cipher of Taso of Boskowitz can only have been made and decorated before his death in August 1482, after which time the Bishopric of Olomouc was briefly ruled by an administrator. Taking all of the evidence into account, it seems reasonable to conclude that the Olomouc pavises discussed above were used by the Moravian followers of Matthias Corvinus in the period 1480-90, and in some, and probably all, cases made before 1482. The present example is likely to have been among the many such pieces plundered from the arsenal in Vienna during the course of the 19th century.

Pavises of this kind were designed to be propped up in front of the archer or crossbowman in the manner illustrated in the Pageant of the Birth, Life and Death of Richard Beauchamp Earl of Warwick of about 1485-90 in the British Library, London. Pavel Zidek recorded in his Liber Viginti Artium of 1413-17, that 'a pavise is made of wood, glue and pieces of canvas which are joined together as thoroughly as possible by glue and well interwoven by ligaments'. According to the herbal of Tadeas Hajek, published in Aventine in 1562, the wood used in making pavises was that of the willow-tree 'because of its stickiness and sinewed character'. A notable feature of the pavises produced in Bohemia was the high quality of their painted decoration. In Prague, there had for some years been a dispute between the shield-makers and the painters about who should apply this decoration. This was eventually resolved at some time before the middle of the 15th century when their two guilds merged into one. So highly valued were the products of the pavise-makers, that the City willingly accepted them in lieu of taxes and military service.

Copyright © 2001 Peter Finer

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Of rectangular shape with rounded corners and a medial gutter of angular section narrowing slightly to a projecting 'beak' at the top, and formed of wood covered with gessoed canvas; the front painted on a white ground with red droplets falling from stylized blue clouds and yellow sun-rays at the top, to flowers of red, yellow and green at the bottom, and superimposed just below its centre with a large escutcheon charged with two rows of red piles or 'passion nails' on a white ground, all enclosed within a border of black, red and white bands; and the rear painted at its upper end, on a black background, with the red initials C and R separated by a white circle bearing in yellow gothic characters outlined in red the Christian device ihs, and fitted with a forked carrying-handle and two iron staples for the attachment of a suspension-loop.

Overall height: 50 1/4 in; Overall width: 21 in

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

The arms forming the central motif of this finely decorated pavise can be identified as those of the Bishopric of Olomouc (Olmutz) in Moravia, then a dominion of the kingdom of Hungary and Bohemia. The same arms are to be seen on three pavises formerly preserved in the Vienna Zeughaus, and now belonging to the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien. One of them (Inv. No. 126.150), is very like that shown here. Another (Inv. No. 126.158), is decorated at its centre with a representation of St George flanked on either side by the arms of Austria and Upper Hungary, and standing above the arms of the Bishopric of Olomouc paired with those of the Moravian family of Boskovic. The third (Inv. No. 126.123), is decorated at its centre with a Czech royal crown over the gothic letter b, almost certainly alluding, once again, to the Boskovic family. There can be little doubt that the pavises discussed above were made for the use of Taso of Boskovic, Prince Bishop of Olomouc from 1457 until his death in 1482. Allied with them is a further pavise in the Viennese collections (Inv. No. 126.114), which is decorated beneath the central figure of St George with the checkered eagle of Moravia, also used as the arms of the city of Olomouc. The pavises in question form part of a larger group evidently abandoned in Vienna by the forces of Matthias Corvinus (1443-90) who occupied the City in the period 1485-90. Some of them bear his personal arms and devices. In the Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, there is a pavise (Inv. No. 55.3264), which probably belonged originally to the group described above. Like the example shown here it is decorated with red droplets falling from the sky but overlain with the crowned gothic M of Matthias Corvinus.

Matthias Corvinus became King of Hungary and Bohemia in 1458, adding Moravia to his territories in 1478. Of the three military expeditions led by him against the Austrians in 1472, 1477 and 1480-85, only the last is likely to have involved the Moravian forces of the Bishop of Olomouc. It resulted in the conquest of the greater part of Austria, and the eventual occupation of Vienna from 1485 until the King's death in 1490. Of the pavises remaining in Vienna, that showing the arms of Upper Hungary in association with those of the Bishopric of Olomouc must have been made, or at the very least repainted, after 1478. On the other hand, the two pavises respectively bearing the personal arms and cipher of Taso of Boskowitz can only have been made and decorated before his death in August 1482, after which time the Bishopric of Olomouc was briefly ruled by an administrator. Taking all of the evidence into account, it seems reasonable to conclude that the Olomouc pavises discussed above were used by the Moravian followers of Matthias Corvinus in the period 1480-90, and in some, and probably all, cases made before 1482. The present example is likely to have been among the many such pieces plundered from the arsenal in Vienna during the course of the 19th century.

Pavises of this kind were designed to be propped up in front of the archer or crossbowman in the manner illustrated in the Pageant of the Birth, Life and Death of Richard Beauchamp Earl of Warwick of about 1485-90 in the British Library, London. Pavel Zidek recorded in his Liber Viginti Artium of 1413-17, that 'a pavise is made of wood, glue and pieces of canvas which are joined together as thoroughly as possible by glue and well interwoven by ligaments'. According to the herbal of Tadeas Hajek, published in Aventine in 1562, the wood used in making pavises was that of the willow-tree 'because of its stickiness and sinewed character'. A notable feature of the pavises produced in Bohemia was the high quality of their painted decoration. In Prague, there had for some years been a dispute between the shield-makers and the painters about who should apply this decoration. This was eventually resolved at some time before the middle of the 15th century when their two guilds merged into one. So highly valued were the products of the pavise-makers, that the City willingly accepted them in lieu of taxes and military service.

Copyright © 2001 Peter Finer

A Very Rare Bohemian Pavise

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Pavise, of wood covered with gesso-covered canvas, and of rectangular form with central gutter of angular section, the front painted with the spear and vinegar-rod crossed, and the crown of thorns of Christ’s Passion, the later painted in green, the sacred monogram ihs above and Maria below, both in Gothic letters, against an overall design of downward-lapping blue scales edged with white, all within a broad red border with a design of running conventional foliage in white, and with original iron stapes and leather brace (incomplete) on the inside (some damage to the bottom and one edge), late 15th century.

Overall height: 50 in

A pavise with almost identical decoration but in poor condition from the Old City Arsenal of Vienna is in the Vienna City Museum, and appears to be the only other recorded example.

Copyright © 1994 Christie's

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Pavise, of wood covered with gesso-covered canvas, and of rectangular form with central gutter of angular section, the front painted with the spear and vinegar-rod crossed, and the crown of thorns of Christ’s Passion, the later painted in green, the sacred monogram ihs above and Maria below, both in Gothic letters, against an overall design of downward-lapping blue scales edged with white, all within a broad red border with a design of running conventional foliage in white, and with original iron stapes and leather brace (incomplete) on the inside (some damage to the bottom and one edge), late 15th century.

Overall height: 50 in

A pavise with almost identical decoration but in poor condition from the Old City Arsenal of Vienna is in the Vienna City Museum, and appears to be the only other recorded example.

Copyright © 1994 Christie's

A Rare Swiss Pavise

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Pavise, of wood covered with gesso-covered canvas, and of rectangular form with wavy top and central gutter of rounded section, the front almost entirely painted with a bold design of scrolling foliage in white against a dark green ground with, at the top, shields of arms comprising those of Habsburg, the League of St. George, and the town of Winterthur, all within a red border, and with original iron stapes and rings on the inside (minor damage and restoration), circa 1445

Overall height: 44 1/2 in

This belongs to a group of pavises, of which some bear only the arms of Winterthur and the League of St. George. The heraldry relates to the war between Austria and Zurich on one hand and the Swiss Confederation on the other. The League of St. George became involved on the Austrian side in 1445.

Copyright © 1994 Christie's

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Pavise, of wood covered with gesso-covered canvas, and of rectangular form with wavy top and central gutter of rounded section, the front almost entirely painted with a bold design of scrolling foliage in white against a dark green ground with, at the top, shields of arms comprising those of Habsburg, the League of St. George, and the town of Winterthur, all within a red border, and with original iron stapes and rings on the inside (minor damage and restoration), circa 1445

Overall height: 44 1/2 in

This belongs to a group of pavises, of which some bear only the arms of Winterthur and the League of St. George. The heraldry relates to the war between Austria and Zurich on one hand and the Swiss Confederation on the other. The League of St. George became involved on the Austrian side in 1445.

Copyright © 1994 Christie's

An Exceptionally Rare Austrian Pavise, circa 1480

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

A superb and rare late 15th century archer's shield or 'pavise' from the Arsenal of Klausen in the South Tyrol, where it was discovered preserved in a tower, forming part of the town walls, when they were demolished in 1871. Preserved in exceptionally good condition, it is made of wood covered with vellum, and is painted with the arms of the Austrian Bindenschild. It probably saw service with the forces of Archduke Siegmund of Tyrol (1427-1496). Shields of this type were either carried or used free-standing, being furnished with an integral prop for support. Due to their slow rate of fire, crossbowmen were particularly vulnerable whilst spanning their bows and therefore had a special need for such protection. This example retains its original handle enabling it to be carried on the march or into battle. This is stunningly simple but nonetheless extremely well-designed and effective, being nothing more than a stout wooden branch split at one end to form the arms of a 'Y', and nailed in place on the back of the shield just above its natural point of balance. This untouched and unrestored pavise is an exceptional survival from the Middle Ages.

Overall height: 49 1/4 in; Overall width: 21 1/2 in

Copyright © Peter Finer

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

A superb and rare late 15th century archer's shield or 'pavise' from the Arsenal of Klausen in the South Tyrol, where it was discovered preserved in a tower, forming part of the town walls, when they were demolished in 1871. Preserved in exceptionally good condition, it is made of wood covered with vellum, and is painted with the arms of the Austrian Bindenschild. It probably saw service with the forces of Archduke Siegmund of Tyrol (1427-1496). Shields of this type were either carried or used free-standing, being furnished with an integral prop for support. Due to their slow rate of fire, crossbowmen were particularly vulnerable whilst spanning their bows and therefore had a special need for such protection. This example retains its original handle enabling it to be carried on the march or into battle. This is stunningly simple but nonetheless extremely well-designed and effective, being nothing more than a stout wooden branch split at one end to form the arms of a 'Y', and nailed in place on the back of the shield just above its natural point of balance. This untouched and unrestored pavise is an exceptional survival from the Middle Ages.

Overall height: 49 1/4 in; Overall width: 21 1/2 in

Copyright © Peter Finer

Bohemian Crossbowman's Pavise, circa 1450

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

The crossbow was relatively slow to load, and the archer could himself become a target while preparing his next shot. One answer to this problem was the pavise, a tall shield which could be propped in front of the bowman when in action. The shield bears the arms of the town of Zwickan in Saxony, and the central monogram may be that of Albrecht of Bohemia. The back of this pavise still has its original T-shaped carrying handle. (The Royal Armouries, London)

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

The crossbow was relatively slow to load, and the archer could himself become a target while preparing his next shot. One answer to this problem was the pavise, a tall shield which could be propped in front of the bowman when in action. The shield bears the arms of the town of Zwickan in Saxony, and the central monogram may be that of Albrecht of Bohemia. The back of this pavise still has its original T-shaped carrying handle. (The Royal Armouries, London)

Very nice Nathan. Those are really cool. Is it just me or is the Swiss one upside-down?

Later,

Later,

| Nate C. wrote: |

| Very nice Nathan. Those are really cool. Is it just me or is the Swiss one upside-down? |

Not any more :) Thanks for the catch

I wish there were more texts out with assembled examples of a piece of equipment like this . Nice line up Nathan!

Can anyone explain to me exactly what gesso is?

| Darwin Todd wrote: |

| Can anyone explain to me exactly what gesso is? |

Plaster of Paris, or gypsum, esp. as prepared for use in painting, or in making bas-reliefs and the like; by extension, a plasterlike or pasty material spread upon a surface to fit it for painting or gilding, or a surface so prepared.

Very interesting topic, thanks again Nathan for all the work you put in researching and posting this one and the other recent armour related topics.

The amazing thing to me is the level of decoration applied to such vulnerable surfaces, that when used as intented would almost certainly be damaged: I guess to the "modern" mind decorations (Valuable art) should not be used where they would risk damage, think about how much a modern sword collector would worry about a single "ding" to even a plain sword.

Think of a highly decorated ship like the 17th century "Royal Sovereign" : All those sculpted and gilded cherubs exposed to potential cannon fire!

I guess pride in workmanship and the prestige of princes overode any concerns about cost and efficiency.

Maybe nicks and dings (Or perfect symmetrie) just didn't seem that much of a problem to the medieval mind?

Or "art/decoration" was just a functionnal thing: Unthinkable to not decorate and art was not put on a "pedestal" as something to be protected at all cost.

But then, for most of history and most cultures, this use of decoration was the norm.

The amazing thing to me is the level of decoration applied to such vulnerable surfaces, that when used as intented would almost certainly be damaged: I guess to the "modern" mind decorations (Valuable art) should not be used where they would risk damage, think about how much a modern sword collector would worry about a single "ding" to even a plain sword.

Think of a highly decorated ship like the 17th century "Royal Sovereign" : All those sculpted and gilded cherubs exposed to potential cannon fire!

I guess pride in workmanship and the prestige of princes overode any concerns about cost and efficiency.

Maybe nicks and dings (Or perfect symmetrie) just didn't seem that much of a problem to the medieval mind?

Or "art/decoration" was just a functionnal thing: Unthinkable to not decorate and art was not put on a "pedestal" as something to be protected at all cost.

But then, for most of history and most cultures, this use of decoration was the norm.

An Important Austro-Burgundian Pavise, circa 1480

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Of oblong, medially hollowed shape with rounded corners, tapering slightly to its lower end which projects downwards in the form of an iron-reinforced central spike; and made of wood covered with gessoed canvas; the front painted on a white ground with a red saltire separatingfour golden fire-steels ornamented with fleurons, each accompanied by a black briquet of elongated quatrefoil form and surrounded by red flames; and the rear fitted with the remains of carrying-handles and straps.

Overall height: 48 in; Overall width: 22 1/4 in

First introduced in the 13th century, the pavise quickly evolved into two main forms: the larger standing pavise that could be propped up in front of the archer or crossbowman, and the relatively smaller hand-pavise favored by other classes of foot-soldier. The stunningly decorated example shown here constitutes a notably large representative of the latter form, equipped at its lower end with an iron-clad spike that could be driven into the ground in order to better resist the onslaught of an opposing army. The method of carrying such a large pavise across the shoulder, by means of a diagonal strap or guige attached at its rear, is well shown in one of the woodcuts of the Ehrenpforte, prepared for the Emperor Maximilian I by Albrecht Dürer in 1515, depicting him among representatives of the different nationalities of his army.

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Interestingly, the principal devices painted on the pavise shown here, namely the saltire and the fire-steels, can also be seen, in conjunction with a double-headed imperial eagle superimposed with the arms of Austria, on a banner of the Emperor Maximilian I, possibly made about 1515 and now preserved in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna (Inv. No. A146). The saltire can be interpreted as the cross of St Andrew, a Burgundian emblem that, along with the fire-steels, briquets and flames seen on the pavise under discussion, became part of the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1470, with St Andrew as its patron. The Burgundian territories included the Low Countries, which, following the marriage of the Archduke Maximilian of Austria, later Emperor Maximilian I, to Mary, daughter and heir of Charles the Bold of Burgundy in 1477, became an imperial province. As a result, Burgundian traditions were appropriated by the Holy Roman Emperors who freely employed the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece as imperial emblems.

The cross of St Andrew, for example, frequently appears on the banners and livery of the imperial troops depicted in the woodcut illustrations of the Weisskunig, an allegorical account, circa 1516, of the life of the Emperor Maximilian I. It also appears as part of the decoration of several surviving suits of armours of the late 15th to early 16th centuries in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna (Inv. Nos. A7, S.VII & A109), and the Real Armeria, Madrid (Cat. No. A15), made not only for the Emperor himself, but also for his son, Philip the Handsome, King of Castile, and his grandson, the Archduke Charles, later Emperor Charles V, who respectively preceded and followed him as Grand Masters of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

On the pavise under discussion the fire-steels are embellished with fleurons, giving them the appearance of crowns, clearly with the intention of conveying to the observer the princely ownership of the piece. Significantly, the modification of the fire-steels to the form of a crown can also be seen in the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece worn by the Emperor Maximilian I in his portrait, painted by Bernard Strigel about 1515, in the Gemaldegalerie, Vienna (Inv. No. 832). It can further be seen in the ornament of a horse armour in the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London (Inv. No. VI. 6-12), given by the Emperor to Henry VIII of England about 1514, but perhaps originally made for his own use, as well as on a sword in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna (Inv. No. A139), recorded as having been worn by him as Archduke of Austria on his triumphal entry into Luxembourg on 29th September 1480. In these circumstances, it seems more reasonable to associate this pavise with Maximilian (1459-1519) than with his son Philip the Handsome (1478-1506) or his grandson Charles V (1500-58), who appear not to have employed the modified form of fire-steel described above. Accepting that, our pavise may even have been made for the use of the troops that followed Maximilian on his campaign into the Low Countries, its Burgundian emblems serving as a visual assertion of his authority over the territory.

Copyright © 2001 Peter Finer

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Of oblong, medially hollowed shape with rounded corners, tapering slightly to its lower end which projects downwards in the form of an iron-reinforced central spike; and made of wood covered with gessoed canvas; the front painted on a white ground with a red saltire separatingfour golden fire-steels ornamented with fleurons, each accompanied by a black briquet of elongated quatrefoil form and surrounded by red flames; and the rear fitted with the remains of carrying-handles and straps.

Overall height: 48 in; Overall width: 22 1/4 in

First introduced in the 13th century, the pavise quickly evolved into two main forms: the larger standing pavise that could be propped up in front of the archer or crossbowman, and the relatively smaller hand-pavise favored by other classes of foot-soldier. The stunningly decorated example shown here constitutes a notably large representative of the latter form, equipped at its lower end with an iron-clad spike that could be driven into the ground in order to better resist the onslaught of an opposing army. The method of carrying such a large pavise across the shoulder, by means of a diagonal strap or guige attached at its rear, is well shown in one of the woodcuts of the Ehrenpforte, prepared for the Emperor Maximilian I by Albrecht Dürer in 1515, depicting him among representatives of the different nationalities of his army.

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Interestingly, the principal devices painted on the pavise shown here, namely the saltire and the fire-steels, can also be seen, in conjunction with a double-headed imperial eagle superimposed with the arms of Austria, on a banner of the Emperor Maximilian I, possibly made about 1515 and now preserved in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna (Inv. No. A146). The saltire can be interpreted as the cross of St Andrew, a Burgundian emblem that, along with the fire-steels, briquets and flames seen on the pavise under discussion, became part of the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1470, with St Andrew as its patron. The Burgundian territories included the Low Countries, which, following the marriage of the Archduke Maximilian of Austria, later Emperor Maximilian I, to Mary, daughter and heir of Charles the Bold of Burgundy in 1477, became an imperial province. As a result, Burgundian traditions were appropriated by the Holy Roman Emperors who freely employed the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece as imperial emblems.

The cross of St Andrew, for example, frequently appears on the banners and livery of the imperial troops depicted in the woodcut illustrations of the Weisskunig, an allegorical account, circa 1516, of the life of the Emperor Maximilian I. It also appears as part of the decoration of several surviving suits of armours of the late 15th to early 16th centuries in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna (Inv. Nos. A7, S.VII & A109), and the Real Armeria, Madrid (Cat. No. A15), made not only for the Emperor himself, but also for his son, Philip the Handsome, King of Castile, and his grandson, the Archduke Charles, later Emperor Charles V, who respectively preceded and followed him as Grand Masters of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

On the pavise under discussion the fire-steels are embellished with fleurons, giving them the appearance of crowns, clearly with the intention of conveying to the observer the princely ownership of the piece. Significantly, the modification of the fire-steels to the form of a crown can also be seen in the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece worn by the Emperor Maximilian I in his portrait, painted by Bernard Strigel about 1515, in the Gemaldegalerie, Vienna (Inv. No. 832). It can further be seen in the ornament of a horse armour in the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London (Inv. No. VI. 6-12), given by the Emperor to Henry VIII of England about 1514, but perhaps originally made for his own use, as well as on a sword in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna (Inv. No. A139), recorded as having been worn by him as Archduke of Austria on his triumphal entry into Luxembourg on 29th September 1480. In these circumstances, it seems more reasonable to associate this pavise with Maximilian (1459-1519) than with his son Philip the Handsome (1478-1506) or his grandson Charles V (1500-58), who appear not to have employed the modified form of fire-steel described above. Accepting that, our pavise may even have been made for the use of the troops that followed Maximilian on his campaign into the Low Countries, its Burgundian emblems serving as a visual assertion of his authority over the territory.

Copyright © 2001 Peter Finer

15th century pavise, Florence?

Attachment: 45.23 KB

Attachment: 45.23 KB

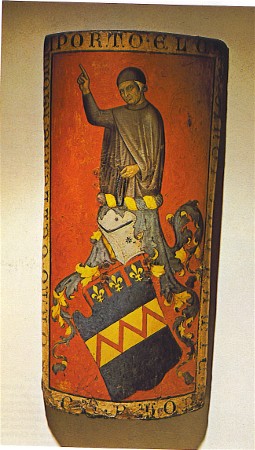

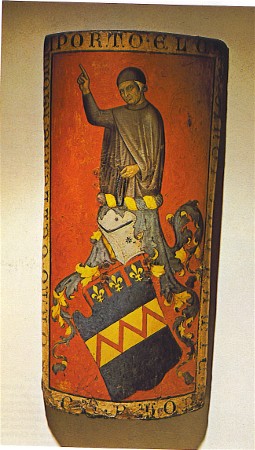

Viennese Master, Circa 1485-1490

The hand-pavise of Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary (1443-90; King, 1458)

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Numerous large, trapezoid pavises and small, rectangular hand-shields have been preserved from the 15th century; all were made with a wide, pronounced medial rib. Examples of this shape go back to western Slavonic sculpture and their traces are lost in the prehistoric darkness of Asia's steppes. In the early 15th century Czech Hussites were equipped with pavises, with which they carried heavy broadswords. The terror spread by the Hussites and their obvious military superiority led to the recruitment of Bohemian warriors for Central European armies and to the adoption of their arms.

A battle for power between the Emperor Frederick III and Matthias Corvinus, the son of the Hungarian regent Johannes Hunyadi, had long been raging in Hungary and devastated Lower Austria. In 1485 even Vienna, the imperial residence, fell to the victorious Hungarian king who reigned there in defiance of the Emperor until his death in 1490. During the war the Bohemian kings Georg Podjebrad and Wladislaw Jagiello had in turn been allied with both parties and Bohemian-Moravian foot-soldiers had fought in both armies. The attractive gilt gesso hand-pavise was modeled on the arms of this select troop and was probably made for King Matthias during his stay in Vienna by a Viennese artist. Around the combined coat of arms of New Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia and Ancient Hungary are grouped the king's further coats of arms and the inscription “Alma genitrix Maria interpella pro rege Mathia”. From the charge on the Hunyadi shield, which impales the central coat of arms, Matthias adopted the surname Corvinus ("The Raven"). After the death of the King, who was not only a doughty warrior but an equally great lover of the arts-the works in his "Corvina" library are world-famous-the young Hapsburg Maximilian fought a quick and victorious campaign to recover the lands lost by his father. It must have been on that occasion that the Hungarian king's pavise came into his possession, as it was in the imperial armoury for three centuries before 1805, when one of Napoleon's generals took it to Paris. Along, heavy broadsword with gilded hilt in Vienna (A 123) may once have belonged to it.

Warriors with this type of Bohemian equipment that occur in the woodcuts in Maximilian's "Triumphal Procession" reminded the aging emperor of the happy victories of his youth.

Paris, Musée de VArmée, I.7

The hand-pavise of Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary (1443-90; King, 1458)

[ Linked Image ]

Click for detailed version

Numerous large, trapezoid pavises and small, rectangular hand-shields have been preserved from the 15th century; all were made with a wide, pronounced medial rib. Examples of this shape go back to western Slavonic sculpture and their traces are lost in the prehistoric darkness of Asia's steppes. In the early 15th century Czech Hussites were equipped with pavises, with which they carried heavy broadswords. The terror spread by the Hussites and their obvious military superiority led to the recruitment of Bohemian warriors for Central European armies and to the adoption of their arms.

A battle for power between the Emperor Frederick III and Matthias Corvinus, the son of the Hungarian regent Johannes Hunyadi, had long been raging in Hungary and devastated Lower Austria. In 1485 even Vienna, the imperial residence, fell to the victorious Hungarian king who reigned there in defiance of the Emperor until his death in 1490. During the war the Bohemian kings Georg Podjebrad and Wladislaw Jagiello had in turn been allied with both parties and Bohemian-Moravian foot-soldiers had fought in both armies. The attractive gilt gesso hand-pavise was modeled on the arms of this select troop and was probably made for King Matthias during his stay in Vienna by a Viennese artist. Around the combined coat of arms of New Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia and Ancient Hungary are grouped the king's further coats of arms and the inscription “Alma genitrix Maria interpella pro rege Mathia”. From the charge on the Hunyadi shield, which impales the central coat of arms, Matthias adopted the surname Corvinus ("The Raven"). After the death of the King, who was not only a doughty warrior but an equally great lover of the arts-the works in his "Corvina" library are world-famous-the young Hapsburg Maximilian fought a quick and victorious campaign to recover the lands lost by his father. It must have been on that occasion that the Hungarian king's pavise came into his possession, as it was in the imperial armoury for three centuries before 1805, when one of Napoleon's generals took it to Paris. Along, heavy broadsword with gilded hilt in Vienna (A 123) may once have belonged to it.

Warriors with this type of Bohemian equipment that occur in the woodcuts in Maximilian's "Triumphal Procession" reminded the aging emperor of the happy victories of his youth.

Paris, Musée de VArmée, I.7

I believe it's Swiatoslawski who documents the pavise as being listed in period sources of the Teutonic Order as a "Prussian shield." Based on what I've seen here and there, I'm inclined to agree that the pavise is a Central or East-Central, rather than Southern European, creation.

it would seem to be related to economic things tho too. what i mean to say is that the value of time (man-hours) is much more exaggerated than it was before. Back then the expensive part of anything was the cost of materials and peoples time wasn't so valued. Everybody worked long hours and that was the way it was. Now days the most expensive commodity is hours. The other thing is that the knights didn't fight all the time with these things. We think of our weapons and things as tools that we use all the time in recreation and training but they used there things only in times of battle which wasn't that common. Its not like a war was happening all the time and every warrior fought daily. Swords arent like construction workers hammers, they're like police officer guns

| Jean Thibodeau wrote: |

| Very interesting topic, thanks again Nathan for all the work you put in researching and posting this one and the other recent armour related topics.

The amazing thing to me is the level of decoration applied to such vulnerable surfaces, that when used as intented would almost certainly be damaged: I guess to the "modern" mind decorations (Valuable art) should not be used where they would risk damage, think about how much a modern sword collector would worry about a single "ding" to even a plain sword. Think of a highly decorated ship like the 17th century "Royal Sovereign" : All those sculpted and gilded cherubs exposed to potential cannon fire! I guess pride in workmanship and the prestige of princes overode any concerns about cost and efficiency. Maybe nicks and dings (Or perfect symmetrie) just didn't seem that much of a problem to the medieval mind? Or "art/decoration" was just a functionnal thing: Unthinkable to not decorate and art was not put on a "pedestal" as something to be protected at all cost. But then, for most of history and most cultures, this use of decoration was the norm. |

| Adam Lloyd wrote: |

| it would seem to be related to economic things tho too. what i mean to say is that the value of time (man-hours) is much more exaggerated than it was before. Back then the expensive part of anything was the cost of materials and peoples time wasn't so valued. Everybody worked long hours and that was the way it was. Now days the most expensive commodity is hours. The other thing is that the knights didn't fight all the time with these things. We think of our weapons and things as tools that we use all the time in recreation and training but they used there things only in times of battle which wasn't that common. Its not like a war was happening all the time and every warrior fought daily. Swords arent like construction workers hammers, they're like police officer guns |

I was talking on the phone with Patrick Kelly the other day and we said almost exactly the same things.

| Nathan Robinson wrote: | ||

I was talking on the phone with Patrick Kelly the other day and we said almost exactly the same things. |

Indeed we were. Excellent points Adam!

Could you supply a bit more information about the action depicted in the woodcut showing Landsknecht and Men-at-arms attacking troops behind pavises? The imperial troops are very familiar for the early 16th century, but the gentlemen behind the shield-wall seem almost a "throwback", and have me quite at a loss.

Page 1 of 9

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum