I got thinking about the historical value of gold and silver recently. All through out time the value of one suit including belt, jacket, and tie has been approximately one gold ounce. Even as a far back as ancient Rome a good Toga, belt, and pair of shoes was about one gold coin. So I got to thinking, does anyone here have any historical knowledge of how many gold or silver ounces a fighting man's sword in the 12th to the 16th's century would cost? I don't mean something exquisite just a working solder's blade like your average XII military arming sword or later XVIIIb longsword.

Today most good replicas from companies like Del Tin, Albion, Arms and Armour, A Trim, etc. cost anywhere from 1/3 of an ounce of gold to a full ounce at the top end considering one ounce of gold has stayed around $1500 give or take $20-$30 or so. In those days I think they would of cost a few gold coins, but I'm not sure. I'm basing this on the fact tact that there was a smaller population and more specie go around during that time period than there was today and that swords tended to be the preferred weapon of the day. Still, it is a curious question. I wonder if the cost of quality swords has gone down or if it has remained the same. I know if you start throwing in budget Chinese and Indian forges it will go down even further in price but they don't tend to match the quality of the American and European forges. Though some of them come close like VA and Hanwei with their Tinker line.

Last edited by Steven Janus on Tue 05 Jul, 2011 11:34 am; edited 1 time in total

Only very recently did gold reach the current (absurdly) high price, only 2 years ago it was 1000$ and 6 years ago it was hovering around the 500$.

It looks like a bubble in the making to me, so I'd say the gold price isn't that useful to compare, even if it is interesting how they compare.

http://www.kitco.com/scripts/hist_charts/yearly_graphs.plx

It looks like a bubble in the making to me, so I'd say the gold price isn't that useful to compare, even if it is interesting how they compare.

http://www.kitco.com/scripts/hist_charts/yearly_graphs.plx

See this thread: http://www.myArmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.php?t...=colonists

During most of the dark ages/middle ages, silver rather than gold was the basis of the monietary system.

Before the late middle ages/renaisance, the only coin in use was a penny, rated at 1/240 pound or mark, depending on location (1 mark beeing roughly 1/2 pound)

Inflation was ripe, however, as governments progressively debased the coins, and more metal became avilable.

After the discovery of the new world, the supply of gold and silver increased dramaticaly, chainging their relation in value. At the same time, large scale transactions made gold coins a viable alternative.

Rather than gold cost, montly cost of living could be seen as a measure of relative value.

Before the late middle ages/renaisance, the only coin in use was a penny, rated at 1/240 pound or mark, depending on location (1 mark beeing roughly 1/2 pound)

Inflation was ripe, however, as governments progressively debased the coins, and more metal became avilable.

After the discovery of the new world, the supply of gold and silver increased dramaticaly, chainging their relation in value. At the same time, large scale transactions made gold coins a viable alternative.

Rather than gold cost, montly cost of living could be seen as a measure of relative value.

Elling no monetary system can escape the laws of inflation and deflation. The larger the monetary supply the more things cost, the smaller the less. Eventually equilibrium is reached once supply catches up to demand, population growth, among other measures. I know that a lot of European countries used a silver standard but I'm confused by what you said. Weren't most societies traditionally bimetal with silver usually being 1/16th the worth of one ounce of gold? As far as debasement, well that's nothing new even for that time period. Rome fell due to currency debasement which led to economic upheaval, civil unrest, crazy price inflation, and the eventual collapse. I know England in particularly was largely silver based. Correct me if I am wrong but their Stirling coins were .999 fine, a rarity among currencies.

Coin clipping, nothing new that's why they started milling coins later on! I disagree though Elling, precious metal is the most consistent method of measuring value. Yes true that the value of metal like anything else can inflate or deflate depending on supply but because the metal actually has to be mined the rate of change in value generally isn't too dramatic. In some instances where a large discovery is found can cause temporary price instability but the markets will work themselves sound again in time. For example, lets say in country A finds a huge silver deposit and prices sky rocket in country A due to the expansion of the monetary supply. Then there is country B which has a smaller monetary supply with cheaper goods and services. People from country A will purchase products from country B until country A starts to run out of monetary supply. As country B receives more silver their prices will start to inflate until they reach equilibrium with the falling prices in country A which is when balance is restored.

Sure there are times like the Tulip Mania of Holland where people jump in on bubbles that eventually collapse but that stuff only happens every so often. I am curious though are these pennies you speak of copper or bronze? Sean I wanted to thank you for that link. If what was said is true in that link that a sword would cost the price of a tiny economy car then you are looking at between seven to eight ounces of gold in today's money, quite expensive!

Job, I don't wish to strain too much into politics but dare I say the bubble is bond market and not precious metals. Yes there has been a great jump in the price recently if valued in paper money. I dare say that the rise in price is merely a response to the increase in monetary supply. The only way to fairly value things over a period of centuries is in precious metals because gold and silver have been consistently the primary currency through out most of humanity. Central banking in Europe wasn't founded until the mid 17th century with the first large one being the Bank of England. By the rise of Napoleon and the following wars Europe by that point had become nations of credit controlled by private banking interest. I don't want to ride too much into it as I do not wish to offend anyone here but from the early day's after the death of Christ up until about the 16th century most merchants demanded hard money with the only exception being a few select banks that were trustworthy enough to operate on full reserves. Those banks mainly just kept the gold in the vault while people traded their deposit receipts until someone decided to redeem it.

Coin clipping, nothing new that's why they started milling coins later on! I disagree though Elling, precious metal is the most consistent method of measuring value. Yes true that the value of metal like anything else can inflate or deflate depending on supply but because the metal actually has to be mined the rate of change in value generally isn't too dramatic. In some instances where a large discovery is found can cause temporary price instability but the markets will work themselves sound again in time. For example, lets say in country A finds a huge silver deposit and prices sky rocket in country A due to the expansion of the monetary supply. Then there is country B which has a smaller monetary supply with cheaper goods and services. People from country A will purchase products from country B until country A starts to run out of monetary supply. As country B receives more silver their prices will start to inflate until they reach equilibrium with the falling prices in country A which is when balance is restored.

Sure there are times like the Tulip Mania of Holland where people jump in on bubbles that eventually collapse but that stuff only happens every so often. I am curious though are these pennies you speak of copper or bronze? Sean I wanted to thank you for that link. If what was said is true in that link that a sword would cost the price of a tiny economy car then you are looking at between seven to eight ounces of gold in today's money, quite expensive!

Job, I don't wish to strain too much into politics but dare I say the bubble is bond market and not precious metals. Yes there has been a great jump in the price recently if valued in paper money. I dare say that the rise in price is merely a response to the increase in monetary supply. The only way to fairly value things over a period of centuries is in precious metals because gold and silver have been consistently the primary currency through out most of humanity. Central banking in Europe wasn't founded until the mid 17th century with the first large one being the Bank of England. By the rise of Napoleon and the following wars Europe by that point had become nations of credit controlled by private banking interest. I don't want to ride too much into it as I do not wish to offend anyone here but from the early day's after the death of Christ up until about the 16th century most merchants demanded hard money with the only exception being a few select banks that were trustworthy enough to operate on full reserves. Those banks mainly just kept the gold in the vault while people traded their deposit receipts until someone decided to redeem it.

Last edited by Steven Janus on Tue 05 Jul, 2011 11:28 am; edited 1 time in total

| Job Overbeek wrote: |

| Only very recently did gold reach the current (absurdly) high price, only 2 years ago it was 1000$ and 6 years ago it was hovering around the 500$.

It looks like a bubble in the making to me, so I'd say the gold price isn't that useful to compare, even if it is interesting how they compare. http://www.kitco.com/scripts/hist_charts/yearly_graphs.plx |

I suggest you check the M3 money supply for US $ or Euro, then check the published inflation levels. Then ask yourself wtf ?

| M van Dongen wrote: | ||

I suggest you check the M3 money supply for US $ or Euro, then check the published inflation levels. Then ask yourself wtf ? |

You mean growth in M3 vs inflation growth?

I can't compare it to US M3 anyway since they stopped publishing those in march 2006, probably because it skyrocketed so much.

Regarding the bubble, I agree that it's even more so in the bond market, but silver for example has dropped over 12% in 3 days a little over a month ago and has only been recently been rising again so to me that seems to indicate gold may be(is) valued too high as well.

There's also the fact that if you look at the gold price around between '95 and '00 it almost drops 50% (compared to 95') so the purchasing power of gold dropped significantly, even with the low inflation levels back then.

On inflation in o.a. the pre-17th century world, wasn't that caused beause they(people in charge) started minting coins of lesser purity, so the purchasing power of the precious metal itself did not become less but the PPP of the coin did?

I seem to recall having seen some graphs with lines showing prices in gold staying near flat until the 17-18th century when banking was introduced.

Anyway I've spend too much time on this very interesting topic, should be getting to back to learning for my exams.

There's an oft-quoted passage in Lord Beveridge's Prices and Wages in England, first published in 1939.

| Quote: |

| At Hinderclay in Suffolk, before the Black Death, wheat was being sold at prices varying with the harvest but ranging about 5s. a quarter; steel was being bought for ploughshares and other implements, at prices also varying from year to year and ranging about 6d. a lb., that is to say, at £50 and upwards per ton. To-day a normal price for wheat is about 50s. a quarter, and for steel is about £10 a ton. While the price of wheat has multiplied ten times, that of steel has fallen to a fifth; a quarter of wheat will buy fifty times as much steel as it once did. The contrast between the wheat age and the steel age could hardly be better illustrated. The difficulties of making index numbers to cover centuries need no further comment. |

Ah just give it time Job. The truth is that the peak for silver will go much higher once people learn about the manipulation in the ETF markets and learn that the world is running out of silver due to the fact that is being used up as an industrial metal. There is actually a lot less silver than there is gold above ground this century. Trust me, silver is LOW if anything now :D. I have no doubt it will be over valued some day, but when that day happens SHTF!

I'm a little confused about the English standard. One pound literately means a pound of silver, is that correct? The shilling penny was then broken up into either 60 or 62 pieces per pound of silver depending on what century you were talking about. One full shilling was 12 to a full pound. That should make one full Shilling 1.33 ounces according to the Frankish standard. It is hard to follow i must say.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_sterling

The reason why it seems hard to follow is because they kept diminishing the weights from what I saw. You're right though about that Job, the coins were debased but at least coin debasement is obvious when it happens. Fiat debasement is much easier to hide. I have to do more research into the monetary units of Shilling. I did make a mistake prior though. The British Stirling is .925 fine. It was before Stirling that they used .999 fine. I will concede that using a high purity coin is bad for currency because silver is too soft and wears too easily. So .9 fine or just above is usually the best, even in the US our coinage until 1965 was .9 fine silver except five cent and once cent pieces.

I'm a little confused about the English standard. One pound literately means a pound of silver, is that correct? The shilling penny was then broken up into either 60 or 62 pieces per pound of silver depending on what century you were talking about. One full shilling was 12 to a full pound. That should make one full Shilling 1.33 ounces according to the Frankish standard. It is hard to follow i must say.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_sterling

The reason why it seems hard to follow is because they kept diminishing the weights from what I saw. You're right though about that Job, the coins were debased but at least coin debasement is obvious when it happens. Fiat debasement is much easier to hide. I have to do more research into the monetary units of Shilling. I did make a mistake prior though. The British Stirling is .925 fine. It was before Stirling that they used .999 fine. I will concede that using a high purity coin is bad for currency because silver is too soft and wears too easily. So .9 fine or just above is usually the best, even in the US our coinage until 1965 was .9 fine silver except five cent and once cent pieces.

| Steven Janus wrote: |

| Elling no monetary system can escape the laws of inflation and deflation. The larger the monetary supply the more things cost, the smaller the less. Eventually equilibrium is reached once supply catches up to demand, population growth, among other measures. I know that a lot of European countries used a silver standard but I'm confused by what you said. Weren't most societies traditionally bimetal with silver usually being 1/16th the worth of one ounce of gold? As far as debasement, well that's nothing new even for that time period. Rome fell due to currency debasement which led to economic upheaval, civil unrest, crazy price inflation, and the eventual collapse. I know England in particularly was largely silver based. Correct me if I am wrong but their Stirling coins were .999 fine, a rarity among currencies. |

Most parts of medieval Latin Christendom issued silver coins (and sometimes copper small change). A few, like late medieval Florence, issued gold and silver. The exchange rate between different currencies was set by the market; the ratio between gold and silver could vary widely over time.

| Job Overbeek wrote: |

| On inflation in o.a. the pre-17th century world, wasn't that caused beause they(people in charge) started minting coins of lesser purity, so the purchasing power of the precious metal itself did not become less but the PPP of the coin did?

I seem to recall having seen some graphs with lines showing prices in gold staying near flat until the 17-18th century when banking was introduced. Anyway I've spend too much time on this very interesting topic, should be getting to back to learning for my exams. |

Debasing the currency was one way. But anything that changed the supply of silver could do it: (loss + exports) exceeding (production + imports), new mines or the exhaustion of old ones, a king from a gold-rich part of Africa setting out on the Haj with a train of bearers carrying gold dust, ...

Then we get into economic change affecting the prices of specific goods: iron objects tended to get cheaper over the course of the middle ages (more people better organized -> more efficient production), and animal products dearer (more people -> less pasture and game). Economic historians tend to use prices in days of labour or kilos of grain for comparative purposes over a long period.

its outside your chosen tme period, but this couple of paragraphs on the vikings swords might open a window somewhat but this might merely refer to the higher tier of sword quality.

| Quote: |

| More than anything else, the sword was the mark of a warrior in the Viking age. They were difficult to make, and therefore rare and expensive. The author of Fóstbræðra saga wrote in chapter 3 that in saga age Iceland, very few men were armed with swords. Of the 100+ weapons found in Viking age pagan burials in Iceland, only 16 are swords.

A sword might be the most expensive item that a man owned. The one sword whose value is given in the sagas (given by King Hákon to Höskuldur in chapter 13 of Laxdæla saga) was said to be worth a half mark of gold. In saga-age Iceland, that represented the value of sixteen milk-cows, a very substantial sum. Swords were heirlooms. They were given names and passed from father to son for generations. The loss of a sword was a catastrophe. Laxdæla saga (chapter 30) tells how Geirmundr planned to abandon his wife Þuríðr and their baby daughter in Iceland. Þuríðr boarded Geirmund's ship at night while he slept. She took his sword, Fótbítr (Leg Biter) and left behind their daughter. Þuríðr rowed away in her boat, but not before the baby's cries woke Geirmundr. He called across the water to Þuríðr, begging her to return with the sword. He told her, "Take your daughter and whatever wealth you want." She asked, "Do you mind the loss of your sword so much?" "I'd have to lose a great deal of money before I minded as much the loss of that sword." "Then you shall never have it, since you have treated me dishonorably." |

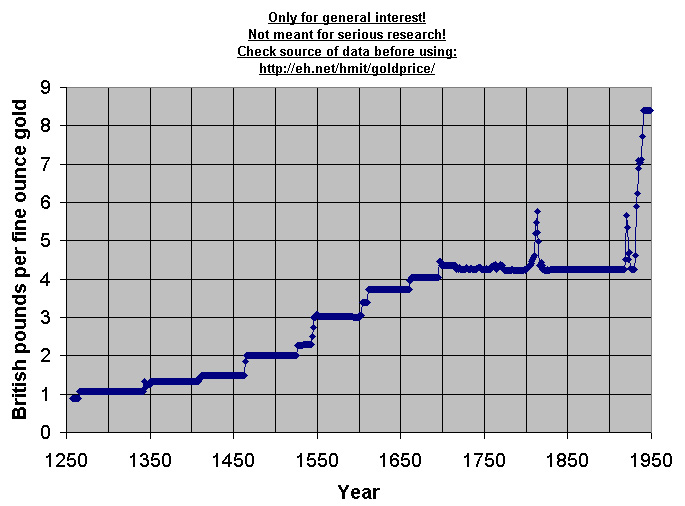

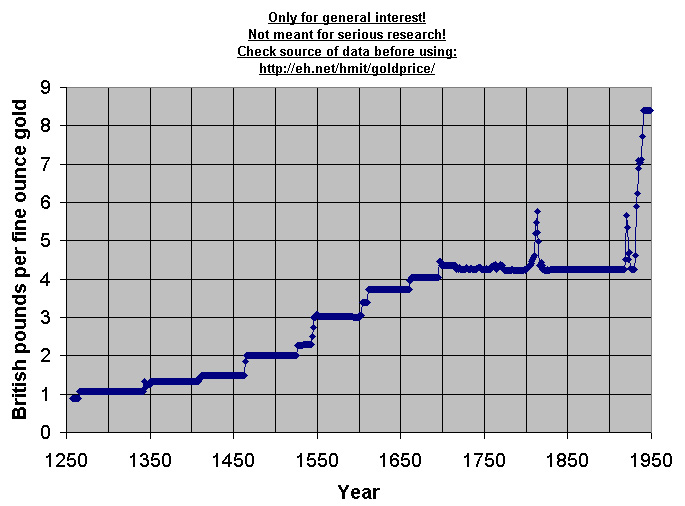

On this website: eh.net/hmit/goldprice you can find an overview of the gold price between 1257 and the modern age. Of course there are a lot of caveats, but it's interesting anyway. I've attached a chart from the data that I made a couple of years ago.

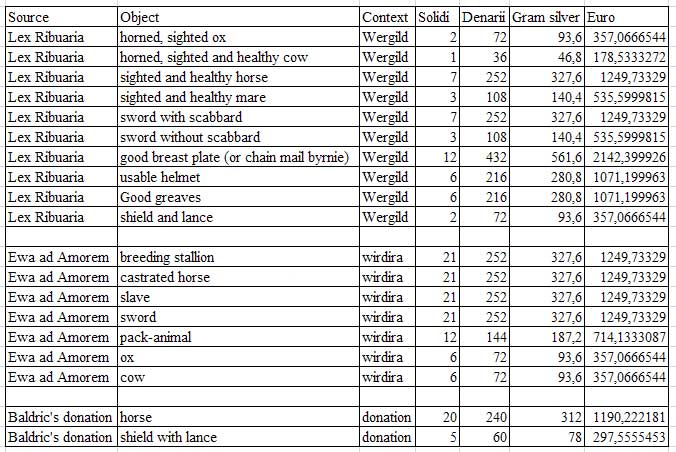

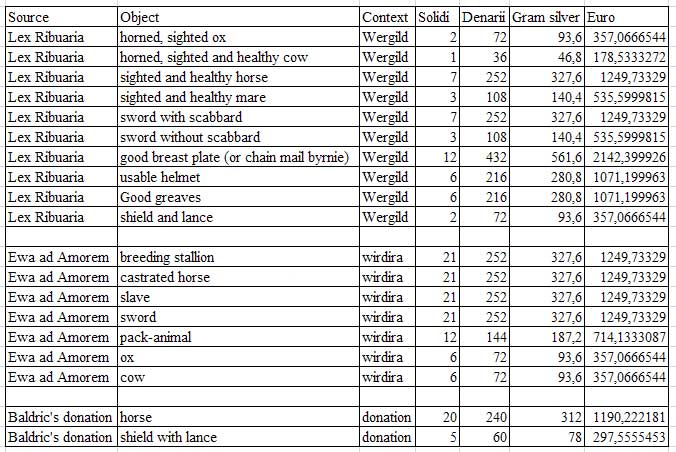

Regarding the price of a sword, there is this overview by Dr. Kees C. Nieuwenhuijsen:

http://www.keesn.nl/price/en2_sources.htm

For easy reference, I compiled it into a table and even translated it via silver weight (I counted 36 denarii per solidus, with a denarius weighing 1,3 grams of fine silver) into a value in Euro. Which is also something that you shouldn't do, obviously... ;) The silver price I used was that of 2009, so perhaps it changed a bit. It's just to give a very, very rough idea anyway. Living standards and wages are obviously completely incomparable. On the other hand, a price of about 1200 Euro for a sword does sound more or less right, doesn't it? :p

Attachment: 61.12 KB

Attachment: 61.12 KB

Attachment: 80.67 KB

Attachment: 80.67 KB

Regarding the price of a sword, there is this overview by Dr. Kees C. Nieuwenhuijsen:

http://www.keesn.nl/price/en2_sources.htm

For easy reference, I compiled it into a table and even translated it via silver weight (I counted 36 denarii per solidus, with a denarius weighing 1,3 grams of fine silver) into a value in Euro. Which is also something that you shouldn't do, obviously... ;) The silver price I used was that of 2009, so perhaps it changed a bit. It's just to give a very, very rough idea anyway. Living standards and wages are obviously completely incomparable. On the other hand, a price of about 1200 Euro for a sword does sound more or less right, doesn't it? :p

| Quote: |

| More than anything else, the sword was the mark of a warrior in the Viking age. They were difficult to make, and therefore rare and expensive. The author of Fóstbræðra saga wrote in chapter 3 that in saga age Iceland, very few men were armed with swords. Of the 100+ weapons found in Viking age pagan burials in Iceland, only 16 are swords.

A sword might be the most expensive item that a man owned. The one sword whose value is given in the sagas (given by King Hákon to Höskuldur in chapter 13 of Laxdæla saga) was said to be worth a half mark of gold. In saga-age Iceland, that represented the value of sixteen milk-cows, a very substantial sum. |

In high medieval Norway, the yearly income from a cow was rated to 1/2 silver mark in value. Half a mark of gold would equal about 10 silver marks, or the income from 20 cows.

Despite their saga tradition, Iceland was a definite backwater in the viking age. This could be amply demonstrated by the low number of weapon finds; In Norway, swords are actually the most common weapon find from the Viking age. This could of course be due to more of them beeing identified and reported, but they still numbered more than 1500 when Pettersen wrote his work on viking swords close to a century ago.

| Elling Polden wrote: |

| The one sword whose value is given in the sagas was said to be worth a half mark of gold. In saga-age Iceland, that represented the value of sixteen milk-cows, a very substantial sum.

(...) In high medieval Norway, the yearly income from a cow was rated to 1/2 silver mark in value. Half a mark of gold would equal about 10 silver marks, or the income from 20 cows. |

So does that mean that milk was more expensive in Iceland or does it mean that Icelandic cows produced more milk?

According to "my" list, a sword would cost 3.5 cows.

The sword in the saga costs 1/2 gold mark, according to you that means 20 cow-years in Norway.

So does that mean that a cow was supposed to be productive for 5.7 years?

Buying a cow outright was priced at about three times the yearly yield, as far as I remember.

Since this was an economy where produced goods where consumed rather than sold, there where fixed "exchange rates" between various agricultural products, and money.

For instance in the 13th century 1/2 mark silver equaled:

1 months provisions

1 years income of a cow

1 years income of 6 sheep.

1 (later increased to 3) laup (15,4 kg, roughly 30 pounds) of butter

1 bushel of corn

3 cow hides

12 goat hides

The most common way to pay large sums was by grating someone a yearly "share" of ones income defined by some unit of value; A cow's share, a month-of-food share (sounds better in norwegian :P), or in actual money; a øre (30 penning) share, a half mark share, and so on.

By these numbers, we can also see that a labourer would earn a little over 1/2 mark a month, as that was the cost of food. Men earning less than 6 marks a year where excempt from the Leidang (leavy).

Since this was an economy where produced goods where consumed rather than sold, there where fixed "exchange rates" between various agricultural products, and money.

For instance in the 13th century 1/2 mark silver equaled:

1 months provisions

1 years income of a cow

1 years income of 6 sheep.

1 (later increased to 3) laup (15,4 kg, roughly 30 pounds) of butter

1 bushel of corn

3 cow hides

12 goat hides

The most common way to pay large sums was by grating someone a yearly "share" of ones income defined by some unit of value; A cow's share, a month-of-food share (sounds better in norwegian :P), or in actual money; a øre (30 penning) share, a half mark share, and so on.

By these numbers, we can also see that a labourer would earn a little over 1/2 mark a month, as that was the cost of food. Men earning less than 6 marks a year where excempt from the Leidang (leavy).

So the big question is how many ounces is one mark of silver? Same thing for gold, how many ounces is one mark of gold?

A mark is a weight unit, which varies slightly from place to place. In high medevial Norway, it was 214,3 g. The Cologne mark, that formed the basis of the later german monitary system, was 233,85 g

An ounce is roughly 30 g. Thus a mark is about 8 ounces.

As for the exact exchange rate between gold and silver, I do not have it on top of my head. Mostly, value was given in silver.

An ounce is roughly 30 g. Thus a mark is about 8 ounces.

As for the exact exchange rate between gold and silver, I do not have it on top of my head. Mostly, value was given in silver.

Thank you for that information Elling. According to Paul's chart one sword with scabbard was 327.6 grams of silver. So I did a conversion of grams to ounces at the following webpage.

http://www.metric-conversions.org/weight/grams-to-ounces.htm

Answer: 327.6 g = 11.5557 oz

http://oil-price.net/

Silver is $36.43 US currently.per ounce. So that means that the sword with scabbard should be $420.97 US.

http://www.metric-conversions.org/weight/grams-to-ounces.htm

Answer: 327.6 g = 11.5557 oz

http://oil-price.net/

Silver is $36.43 US currently.per ounce. So that means that the sword with scabbard should be $420.97 US.

Page 1 of 1

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum