After a decade or so of collecting weapons, my mind has started to turn the direction of armor. For context, I've targeted 1350 as my time frame (give or take a decade), German/English as my preferred regional influences.

I've found it easy enough to research the metal components as there's plenty of easily accessible information (antiques, period art, effigies, etc.). My problem is, I don't want to start ordering armor without the right foundation garments because the foundation garments affect the measurements. And, since the foundation garments are worn under the armor, and not of durable materials, art, effigies and antiques all leave me scratching my head.

Particularly when it comes to the legs.

At least in the early part of the 14th century, it appears that maille chausses were the norm, or at least one of several concurrent norms, with plate components strapped over them. So what's under those maille chausses? Some kind of "gamboised" or padded linen chausses? (I'd think you'd want padding in the system somewhere.) Normal civilian linen chausses? And what are all the layers pointed to? The fabric, maille, and plate layers all need to be suspended from the hips somehow. Are they all pointed together, or do we have the fabric layer suspended from braies, and the maille and plate suspended to an arming cotte or a padded foundation garment on the torso?

Further, have we got any evidence that shoes were worn in there anywhere? The sabatons have to be attached to something. Riveted directly to the "foot" of the textile chausses? Pointed through a maille layer to the textile layer?

Hopefully history leaves us something to point to and exclaim "aha!" but whatever such a thing might be, I haven't been able to dig it up.

So . . . any help out there?

| Michael S. Rivet wrote: |

| After a decade or so of collecting weapons, my mind has started to turn the direction of armor. For context, I've targeted 1350 as my time frame (give or take a decade), German/English as my preferred regional influences.

I've found it easy enough to research the metal components as there's plenty of easily accessible information (antiques, period art, effigies, etc.). My problem is, I don't want to start ordering armor without the right foundation garments because the foundation garments affect the measurements. And, since the foundation garments are worn under the armor, and not of durable materials, art, effigies and antiques all leave me scratching my head. Particularly when it comes to the legs. At least in the early part of the 14th century, it appears that maille chausses were the norm, or at least one of several concurrent norms, with plate components strapped over them. So what's under those maille chausses? Some kind of "gamboised" or padded linen chausses? (I'd think you'd want padding in the system somewhere.) Normal civilian linen chausses? And what are all the layers pointed to? The fabric, maille, and plate layers all need to be suspended from the hips somehow. Are they all pointed together, or do we have the fabric layer suspended from braies, and the maille and plate suspended to an arming cotte or a padded foundation garment on the torso? Further, have we got any evidence that shoes were worn in there anywhere? The sabatons have to be attached to something. Riveted directly to the "foot" of the textile chausses? Pointed through a maille layer to the textile layer? Hopefully history leaves us something to point to and exclaim "aha!" but whatever such a thing might be, I haven't been able to dig it up. So . . . any help out there? |

We actually know quite a bit about this, although some of it is, admittedly, extrapolation. The big question, however, is "when in the 14th century?" because transitional armor was, obviously, transitioning, and some kinds of gear required one thing and some another. If you're referring to the beginnings of plate, then we have pretty good evidence and extrapolation to go by.

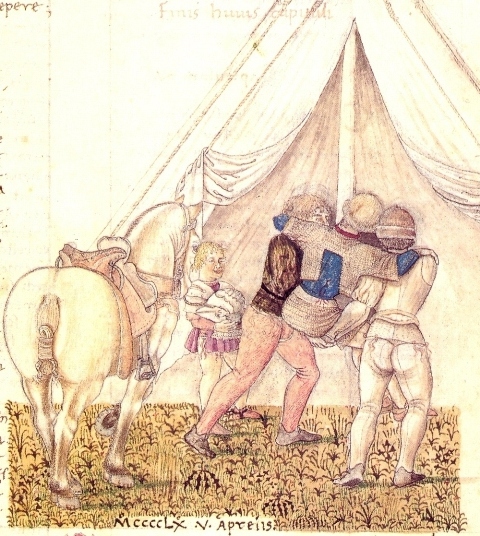

The first picture attached below from Français 343 fol. 32 shows a 14th-century French knight with his harness off; you can see the arming doublet quite plainly beside him. This doublet seems to have been similar to the Charles de Blois pourpoint, even though that garment was very clearly a civilian garment, but the principles of construction remain the same. You can't really see the grand aissette sleeve in the Graal painting, but the shape of the garment suggests it, to me, at least. I confess I'm confused by the straight sleeve on the Graal doublet, however, so either the garment isn't completely identical, or the artist was just sloppy. This garment would have supported both the hosen (although they could have been on a sleeveless pourpoint, too) and the cuisses.

As for the hosen themselves, I think it quite unlikely that mail chausses would have been worn. First, much art shows colored hosen; the figure on the right in Graal fol. 14r below, for example, clearly has a red leg with only a patch of mail at the knee, and second, full mail chausses just don't fit well under plate legs. My friend Will McLean has a theory about "panzerhosen" which I think adequately explains the probable solution--patches of mail sewn to hosen, just as with voiders on the doublet. You can read more about this, and see examples, here:

http://willscommonplacebook.blogspot.com/2010/11/panzerhose.html

As for the sabatons, we're fortunate in having an extant pair that show us the answer. You can see one of Charles' sabatons below. Note the two holes on the toe cap; these are for points which attach to the shoes below. You can see a picture of me wearing a pair of almost identical design below, too. Here is an excerpt from a 15th-century document entitled "How A Man Shall Be Armed To Fight on Foot" (Hastings MS. f.122b) which tells us about this:

"He should wear a pair of thick shoes, provided with points sewn on the heel and in the middle of the sole to a space of three fingers. First you must set the sabatons and tie them to the shoe with small points that will not break."

So he's wearing heavy leather shoes with knotted cords stitched to the soles to give traction (which I think is a neat insight), and then the sabatons are tied to the shoes with points, just as in the Charles VI examples.

I hope this helps.

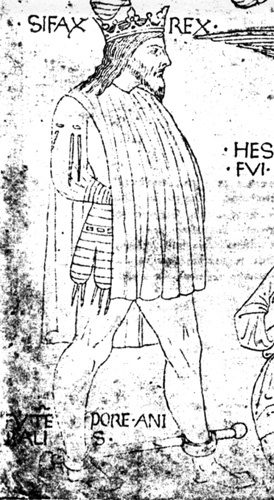

Français 343 - Queste del Saint Graal fol. 32

Français 343 - Queste del Saint Graal fol. 14r

Hugh's Sabatons

Charles VI sabaton [ Download ]

I actually did state at the beginning that I'm looking at 1350, approximately. Which is almost as good as not specifying a date at all because just about everything seems to have been common, be it on its way in or on its way out at that point.

The sabaton bit makes perfect sense! Thanks so much for that. I'd somehow never caught the toe holes. So the points on the soles of the feet, do you pull those around and attach them to the sides of the sabatons?

Regarding the arming doublet . . . what you're saying makes sense, but the artist hasn't given us any lines to indicate points. And, of course, the extant "pourpoint" or "cotte" or "jack" of Charles de Blois isn't an arming garment per se so it doesn't have any points, either. Unless they're not visible from the outside. Frankly, the way the hem of that particular type of garment is designed, and how low it appears to want to hang, makes it look really awkward for hanging chausses or cuisses. The idea of having a sleeveless pourpoint underneath it makes all kinds of sense, though.

Lastly, the notion of "leg voiders" seems very efficient and sensible. But I'm not sure I buy it as "the" solution. The full hauburgen persisted for a long time under plate or coat-of-plates. If they were stacking plate on their existing arm and torso maille, I can't imagine that wasn't the practice for the legs as well. In varying degrees over time, of course, as folks start to ask themselves "why am I wearing all this steel under all this steel?"

Also, just a quirky observation: the blog article you linked to shows several paintings all of which appear to be from the Graal. Many show the brown or red colored back of the thigh. But only ever on one leg. One leg will have a red back to the thigh, the other will have gray -- like the rest of the armor. It's sometimes a little hard to figure out which leg is which, but it looks like the artist is only intending to show the inner part of the thigh as unarmored. For a while I wondered if that was meant to be leather, but since you can clearly see the strap holding the cuisses on I don't know why there'd be leather there. I still wouldn't want to be stabbed there, mind.

The sabaton bit makes perfect sense! Thanks so much for that. I'd somehow never caught the toe holes. So the points on the soles of the feet, do you pull those around and attach them to the sides of the sabatons?

Regarding the arming doublet . . . what you're saying makes sense, but the artist hasn't given us any lines to indicate points. And, of course, the extant "pourpoint" or "cotte" or "jack" of Charles de Blois isn't an arming garment per se so it doesn't have any points, either. Unless they're not visible from the outside. Frankly, the way the hem of that particular type of garment is designed, and how low it appears to want to hang, makes it look really awkward for hanging chausses or cuisses. The idea of having a sleeveless pourpoint underneath it makes all kinds of sense, though.

Lastly, the notion of "leg voiders" seems very efficient and sensible. But I'm not sure I buy it as "the" solution. The full hauburgen persisted for a long time under plate or coat-of-plates. If they were stacking plate on their existing arm and torso maille, I can't imagine that wasn't the practice for the legs as well. In varying degrees over time, of course, as folks start to ask themselves "why am I wearing all this steel under all this steel?"

Also, just a quirky observation: the blog article you linked to shows several paintings all of which appear to be from the Graal. Many show the brown or red colored back of the thigh. But only ever on one leg. One leg will have a red back to the thigh, the other will have gray -- like the rest of the armor. It's sometimes a little hard to figure out which leg is which, but it looks like the artist is only intending to show the inner part of the thigh as unarmored. For a while I wondered if that was meant to be leather, but since you can clearly see the strap holding the cuisses on I don't know why there'd be leather there. I still wouldn't want to be stabbed there, mind.

| Michael S. Rivet wrote: |

| The sabaton bit makes perfect sense! Thanks so much for that. I'd somehow never caught the toe holes. So the points on the soles of the feet, do you pull those around and attach them to the sides of the sabatons? |

No, the cords attached to the soles of the shoes aren't points, they're actually like medieval cleats, for traction. I just realized I copied the wrong bit of text for that--the one I used is a version that's floating around the web, but it's actually incorrectly modernized and also incomplete. Here's a more accurate modernization I did:

"He should wear a pair of shoes of thick leather, and they must be fretted with thin whipcord with three knots and three such cords must be sewn on the heel of the shoe and in the middle of the shoe and there must be a space of three fingers between the frets on the heel and the frets on the middle of the shoe."

So, you see, you take six pieces of whipcord (not heavier material such as you'd use for points), and tie 3 knots in each (the knots are what provide the traction--they're the cleats, if you will). You sew three pieces of the knotted whipcord to the heel, and three to the middle of the shoe. That way, you get better traction on smooth ground.

Having said that, on the Charles VI sabatons, Mac put a strap under the instep of the foot and the strap ties to the inside side of the sabaton to hold it on. You don't need to do that with sabatons that have a heel plate because you can point the heel plate to the back of your shoe.

| Quote: |

| Regarding the arming doublet . . . what you're saying makes sense, but the artist hasn't given us any lines to indicate points. And, of course, the extant "pourpoint" or "cotte" or "jack" of Charles de Blois isn't an arming garment per se so it doesn't have any points, either. Unless they're not visible from the outside. Frankly, the way the hem of that particular type of garment is designed, and how low it appears to want to hang, makes it look really awkward for hanging chausses or cuisses. The idea of having a sleeveless pourpoint underneath it makes all kinds of sense, though. |

I don't believe that arming doublet is any longer than a Charles de Blois poirpoint, and I know *lots* of reenactors who have used that design to hold up their legs (including me), so it's definitely not too long. The points don't need to be at the bottom edge of the doublet, they can be farther up inside, just as the points are in the Charles de Blois poirpoint. As for the artist not showing the points, this MS just isn't that detailed--little 14th century art is. The coat armor is lying on the ground, so this *must* be the arming doublet.

| Quote: |

| Lastly, the notion of "leg voiders" seems very efficient and sensible. But I'm not sure I buy it as "the" solution. The full hauburgen persisted for a long time under plate or coat-of-plates. If they were stacking plate on their existing arm and torso maille, I can't imagine that wasn't the practice for the legs as well. In varying degrees over time, of course, as folks start to ask themselves "why am I wearing all this steel under all this steel?" |

I hope I didn't come across as saying this was the only way it was done. As you know, I'm sure, this period was one of experimentation, and I'm sure lots of techniques were tried for all of these things.

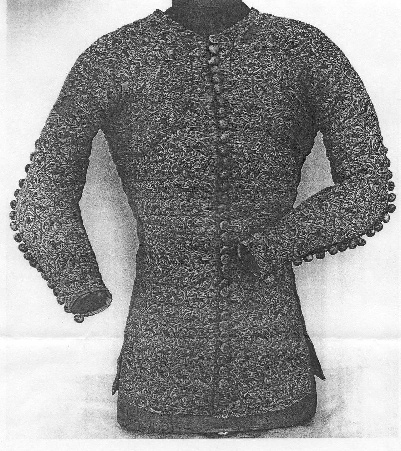

As for "stacking plate over mail" as you put it, I don't agree. The sleeves of a haubergeon would come down just inside the upper edge of the lower cannons, no more. Haubergeons were worn, but when they were complete it was usually because they needed the protection, for example, with a breastplate with no backlplate (e.g., the Pistoia alterpiece). When full body armor was worn, we know that at least some of the time they wore partial haubergeons, as in the attached picture showing one. Worn with a mail skirt, this would show up in a fully armed picture as if it was a full haubergeon, but it's not.

The legs are like the vambraces in this regard: If the cuisses are like the upper cannons and the greaves like the lower cannons of the vambraces, then the mail doesn't extend into the greaves any more than it does into the lower cannons of the vambraces. Sure, you can wear mail shorts (and they did), but they won't extend down into the greaves.

| Quote: |

| Also, just a quirky observation: the blog article you linked to shows several paintings all of which appear to be from the Graal. Many show the brown or red colored back of the thigh. But only ever on one leg. One leg will have a red back to the thigh, the other will have gray -- like the rest of the armor. It's sometimes a little hard to figure out which leg is which, but it looks like the artist is only intending to show the inner part of the thigh as unarmored. For a while I wondered if that was meant to be leather, but since you can clearly see the strap holding the cuisses on I don't know why there'd be leather there. I still wouldn't want to be stabbed there, mind. |

There are quite a few other examples where you can see color on both thighs--I think this is just a quirk of this MS artist.

Precursor to voiders

| Michael S. Rivet wrote: |

| Regarding the arming doublet . . . what you're saying makes sense, but the artist hasn't given us any lines to indicate points. And, of course, the extant "pourpoint" or "cotte" or "jack" of Charles de Blois isn't an arming garment per se so it doesn't have any points, either. Unless they're not visible from the outside. Frankly, the way the hem of that particular type of garment is designed, and how low it appears to want to hang, makes it look really awkward for hanging chausses or cuisses. The idea of having a sleeveless pourpoint underneath it makes all kinds of sense, though. |

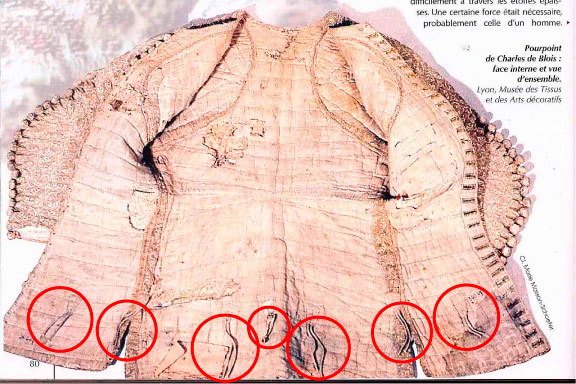

I just realized from the way that you wrote that that you may not have seen the points on the Charles de Blois pourpoint. It definitely is a pourpoint, or "for points." It's not a cotte or jack because it's clearly a civilian garment. First, it's made of very high-quality brocade, and the brocade isn't worn in the way armor would have worn it. Second, the sleeve buttons are much too large to fit under the lower cannons of vambraces. So the CdeB garment is *clearly* not an arming doublet, but we can extrapolate from the set of the grande aissette sleeves how an arming doublet of this style would work; note that the body is shaped just as the body of the arming doublet in the Graal painting in my first post.

As for the points, please see the first attached picture. As you can see, there are 7 points, all intended to hold up hosen (not cuisses). I'm have a source that says the 4 to the front are fabric and the three in the back are kid, but I can't find my reference for that right at the moment. Note how far up inside the garment the points are: This is why a longer garment can still hold up cuisses.

Please look at the 2nd attached picture to see that there are no armor wear marks, demonstrating that this is obviously a civilian garment.

Inside of the CdeB pourpoint

CdB pourpoint, front

I think it is important to look deeper into some points her.

First of all, it is a common misconception "pourpoint" comes from "for the points". "Pourpoint" is middle french and means nothing else then "quilted": "pourpoindre" means "stiched through". "Pour points" is a mixture between modern french and middle english. The garment of charles de blois is dated about 1363, and first mentionings of exact that type of garment, called "paltock" can be found in 1367 in the english wardrobe accounts. I would not expect it any earlier in english wardrobe, and there is no indication it was common in germany at all up to my knowledge. In the 1360s, is is pretty hard to find any trace of a doublet-like garment in german sources. All sources I know still show chausses being attached to the brais.

Secondly: As mentioned, the garment of charles de blois is civil. Made to hold up chausses (wuite modern ones extending to the back, or even early closes ones). You don't need that cut for something worn underneath armour. Of course you _can_ war something alike, but more of that lateron.

Next: why always the search for a specific arming garment? In fact you don't need any in the 1350s to 1360s. We have lots of sources, both text sources (again, the wardrobe accounts of the english crown as a common example, which can be found e.g. in "fashion in the age of the black prince") as well as effigies showing partly textile armour being worn underneath the maille shirt, named "aketon" (but interchangingle with "doublet etc.!).

Textile armour. Important difference. Textile armour is made to protect the wearer. -NOT- For padding. -NOT- For showing a specifiy body shape. The garment of charles de blois is quilted, yes, but a lot of garments were quitled in the middle ages. It is fileld with raw cotton wool, yes, which is also true for most surviving textle armours. -BUT_ the garment of charles de blois is _padded_ at the chest, to achieve a specific shiluette.

Now the thing is: you _can_ wear simply civil clothing underneath armour. There are lots of examples for different parts of the middle ages. From the 13th century, the 14th, the 15th. You do not need something quilted. You don't need something padded. Even if the civil garment of that period, which is fashionable, is quilted, this is not why you wear it.

And even if you really really really really need laces to lace your armour to the garment you are wearing underneath (which is only true for very few occurances, and for many examples which are common among reenactors there are hardly evidences), then you simply sew laces to the garment. Takes less than 5minutes,works finde.

You can even sew laces to textile armour, in case what you wear underneath is some kind of that, because you want to get extra safetly (which seems to had been the case for about 1350). There are also examples for that in the 1350s.

But is one of the garments a specific arming garment? No, it isn't. Either textile armour, or a civil garment.

And even if sources mention "arming doublets" (and so on) we hardly ever know what makes them "arming".

I think it is very very important to do three things:

-Not mix post-1350s surviving garments and armour with that of 1350, and over all regions

-To make a distinction between the construction of garments, not between the purpose: we often don't know it

-Not to stick to old reenactorisms

Now for the sake of the initial post:

If you want to build a 1350 armour, please be specific. As good as you can. Armour from 1355 may look differently than from 1350, and especially there are -huge- differences between regions, or nations. German armour from 1350 is often completly different from englis in 1356.

German armour from 1350 would not have sabatons. It would consist, generally, of shirt, brais, old-fashioned chausses, maille chausses -attached to some kind of belt-, textile armour cuisses (attached to the same belt), perhaps shinbards, knee cops, aketon, perhaps vambraces, haubergion, perhaps seperate maille collar, coat of plates, early gauntlets (NO hourglas!), bascinet, great helmet.

Germany was old fashioned when it came to armour in the 14th century.

As for the attachment of the lag armour: I know no real source pointing to attach it to a doublet. If anyone knows any, please quote it, I would be happy. The sources I know for the 13th and 14th century mention the "lendenier" which was sometimes attached to the "huffenier". The "lendenier" can be made from textile, quilted, and laced, according to second haft-of-the-14th-century sources (limburg chronicles being a prominent example). In the 13th century it seems to had been simply a belt.

As for underneath maille chausses: civil ones. No "padding" or textile armour. The textile armour cuisses come _over_ them, reducing the energie of incoming projectiles, so that they cannot pass the maille. Which is also the sense of the textile armour in general, by the way, not because it is more comfortable to wear maille...

First of all, it is a common misconception "pourpoint" comes from "for the points". "Pourpoint" is middle french and means nothing else then "quilted": "pourpoindre" means "stiched through". "Pour points" is a mixture between modern french and middle english. The garment of charles de blois is dated about 1363, and first mentionings of exact that type of garment, called "paltock" can be found in 1367 in the english wardrobe accounts. I would not expect it any earlier in english wardrobe, and there is no indication it was common in germany at all up to my knowledge. In the 1360s, is is pretty hard to find any trace of a doublet-like garment in german sources. All sources I know still show chausses being attached to the brais.

Secondly: As mentioned, the garment of charles de blois is civil. Made to hold up chausses (wuite modern ones extending to the back, or even early closes ones). You don't need that cut for something worn underneath armour. Of course you _can_ war something alike, but more of that lateron.

Next: why always the search for a specific arming garment? In fact you don't need any in the 1350s to 1360s. We have lots of sources, both text sources (again, the wardrobe accounts of the english crown as a common example, which can be found e.g. in "fashion in the age of the black prince") as well as effigies showing partly textile armour being worn underneath the maille shirt, named "aketon" (but interchangingle with "doublet etc.!).

Textile armour. Important difference. Textile armour is made to protect the wearer. -NOT- For padding. -NOT- For showing a specifiy body shape. The garment of charles de blois is quilted, yes, but a lot of garments were quitled in the middle ages. It is fileld with raw cotton wool, yes, which is also true for most surviving textle armours. -BUT_ the garment of charles de blois is _padded_ at the chest, to achieve a specific shiluette.

Now the thing is: you _can_ wear simply civil clothing underneath armour. There are lots of examples for different parts of the middle ages. From the 13th century, the 14th, the 15th. You do not need something quilted. You don't need something padded. Even if the civil garment of that period, which is fashionable, is quilted, this is not why you wear it.

And even if you really really really really need laces to lace your armour to the garment you are wearing underneath (which is only true for very few occurances, and for many examples which are common among reenactors there are hardly evidences), then you simply sew laces to the garment. Takes less than 5minutes,works finde.

You can even sew laces to textile armour, in case what you wear underneath is some kind of that, because you want to get extra safetly (which seems to had been the case for about 1350). There are also examples for that in the 1350s.

But is one of the garments a specific arming garment? No, it isn't. Either textile armour, or a civil garment.

And even if sources mention "arming doublets" (and so on) we hardly ever know what makes them "arming".

I think it is very very important to do three things:

-Not mix post-1350s surviving garments and armour with that of 1350, and over all regions

-To make a distinction between the construction of garments, not between the purpose: we often don't know it

-Not to stick to old reenactorisms

Now for the sake of the initial post:

If you want to build a 1350 armour, please be specific. As good as you can. Armour from 1355 may look differently than from 1350, and especially there are -huge- differences between regions, or nations. German armour from 1350 is often completly different from englis in 1356.

German armour from 1350 would not have sabatons. It would consist, generally, of shirt, brais, old-fashioned chausses, maille chausses -attached to some kind of belt-, textile armour cuisses (attached to the same belt), perhaps shinbards, knee cops, aketon, perhaps vambraces, haubergion, perhaps seperate maille collar, coat of plates, early gauntlets (NO hourglas!), bascinet, great helmet.

Germany was old fashioned when it came to armour in the 14th century.

As for the attachment of the lag armour: I know no real source pointing to attach it to a doublet. If anyone knows any, please quote it, I would be happy. The sources I know for the 13th and 14th century mention the "lendenier" which was sometimes attached to the "huffenier". The "lendenier" can be made from textile, quilted, and laced, according to second haft-of-the-14th-century sources (limburg chronicles being a prominent example). In the 13th century it seems to had been simply a belt.

As for underneath maille chausses: civil ones. No "padding" or textile armour. The textile armour cuisses come _over_ them, reducing the energie of incoming projectiles, so that they cannot pass the maille. Which is also the sense of the textile armour in general, by the way, not because it is more comfortable to wear maille...

| Jens Boerner wrote: |

| First of all, it is a common misconception "pourpoint" comes from "for the points". "Pourpoint" is middle french and means nothing else then "quilted": "pourpoindre" means "stiched through". "Pour points" is a mixture between modern french and middle english. |

Thank you for that correction of the translation; it seems that's one of those mistranslation's that's become so accepted that no one even questions it any longer.

| Quote: |

| Next: why always the search for a specific arming garment? |

That should be obvious: So that we can copy it accurately.

| Quote: |

| In fact you don't need any in the 1350s to 1360s. We have lots of sources, both text sources (again, the wardrobe accounts of the english crown as a common example, which can be found e.g. in "fashion in the age of the black prince") as well as effigies showing partly textile armour being worn underneath the maille shirt, named "aketon" (but interchangingle with "doublet etc.!). |

I'm sorry, but the term aketon should, more correctly, be used to refer to the quilted garment worn under great hauberks in the 12th and 13th centuries (see Blair pp. 32-33). Thus, the term is not interchangeable with "arming doublet," which is usually used today to refer to a more fitted garment, such as the type shown in the Graal MS.

| Quote: |

| Now the thing is: you _can_ wear simply civil clothing underneath armour. |

You can do anything you want, but many things will be uncommon. I don't understand your point. As with the CdB pourpoint, many civilian garments will be unsuitable for arming garments for one reason or another. In the case of the CdB pourpoint, for example, the sleeve buttons are too big and will not allow the lower cannons of the vambraces to fit correctly.

| Quote: |

| There are lots of examples for different parts of the middle ages. From the 13th century, the 14th, the 15th. You do not need something quilted. You don't need something padded. Even if the civil garment of that period, which is fashionable, is quilted, this is not why you wear it. |

You need it to be quilted if the garment was typically quilted in period. Again, however, I'm not sure of your point. No one in this thread has discussed a single quilted arming garment. Yes, the pourpoint of CdB is quilted, but as I said (and you agreed) that's a civilian garment which is quilted in order to give a specific body shape. As far as my research has shown, arming doublets were typically *not* quilted because they didn't need to be. You don't need padding under a breastplate! They were, however, stitched with narrow lines to give support to the garment and to hold the outer shell to the lining without sliding under stress, just as we see in the Graal painting above. On the other hand, King Rene's book of the tournament specifically calls for arming doublets to be padded over the shoulders, but we can't be sure how common that was; it may have been specific to the type of tournament (fought with rebated swords and clubs) to which Rene was referring.

| Quote: |

| And even if you really really really really need laces to lace your armour to the garment you are wearing underneath (which is only true for very few occurances, and for many examples which are common among reenactors there are hardly evidences), then you simply sew laces to the garment. Takes less than 5minutes,works finde. |

They're you're wrong, if I understand you correctly (and I'm not sure I do). Armor *was* pointed to arming clothing with points. Whether it was attached to tabs or directly to the foundation garment varies from source to source, but we have *lots* of evidence that points were used to attach armor to foundation garments. The Hastings MS I referenced above talks about this very specifically, even telling us how to make the points.

| Quote: |

| But is one of the garments a specific arming garment? No, it isn't. Either textile armour, or a civil garment.

And even if sources mention "arming doublets" (and so on) we hardly ever know what makes them "arming". |

I think we're having a language problem here. This makes no sense to me; can you explain it differently?

| Quote: |

| -Not mix post-1350s surviving garments and armour with that of 1350, and over all regions |

No one has done that here.

| Quote: |

| -To make a distinction between the construction of garments, not between the purpose: we often don't know it |

Sure we do, we have lots of art showing this.

| Quote: |

| -Not to stick to old reenactorisms |

Again, no one has done that here.

| Quote: |

| As for the attachment of the lag armour: I know no real source pointing to attach it to a doublet. If anyone knows any, please quote it, I would be happy. |

As far as I know, the *only* sources we have showing the attachment of cuisses shows them being attached to the doublet. It is late here and I need to go to bed, but I will look some up for you if you like.

| Quote: |

| As for underneath maille chausses: civil ones. No "padding" or textile armour. The textile armour cuisses come _over_ them, reducing the energie of incoming projectiles, so that they cannot pass the maille. Which is also the sense of the textile armour in general, by the way, not because it is more comfortable to wear maille... |

Who said anything about wearing padded garments under chausses?

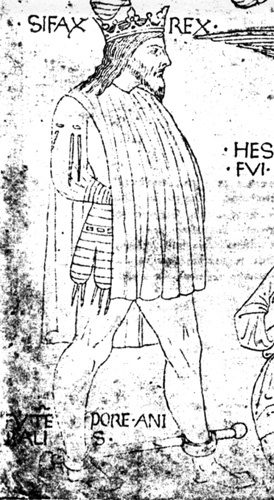

I found one picture I have showing arming points for both the vambraces and the cuisses. Please see attached. Note that the points on his arm are not merely stitched to the sleeve, but are laced through holes.

Attachment: 103.02 KB

Attachment: 103.02 KB

Hey Hugh, do you think that those lines on his forarms and waist represent some form of extra 'padding' as it were?

And, refering to Rene, he does say to pad the length of ones arms more? Off topic, but just a query.

And, refering to Rene, he does say to pad the length of ones arms more? Off topic, but just a query.

| Sam Gordon Campbell wrote: |

| Hey Hugh, do you think that those lines on his forarms and waist represent some form of extra 'padding' as it were?

And, refering to Rene, he does say to pad the length of ones arms more? Off topic, but just a query. |

Hello,

I don't know exactly what those lines mean--a lot of Italian doublets show lines in that direction on the forearm (or even entire arm), even when the stitch lines are in the other direction on the upper arms and body. I do know that the lines don't necessarily refer to padding (they were often used to stitch the outer to the inner shell for more stability) and that arming garments weren't typically padded, but that doesn't necessarily preclude you from being right.

Here is exactly what Rene says about the arming garment:

"in whatever kind of body harness you wish to tourney, it is necessary that the harness be big and ample enough in all places that you may wear a pourpoint or corset underneath. It is necessary that the pourpoint be padded to three fingers' thickness on the shoulders and the length of the arms up to the neck, and on the back also, because the blows of maces and swords fall more frequently on these places than elsewhere." (Rene of Anjou, King Rene's Tournament Book: Traictie de la forme et devis d'ung tournoy. Translated by Elizabeth Bennett. 2nd ed. rev., 1997.)

You can read the entire illustrated translation here: http://www.princeton.edu/~ezb/rene/renehome.html

In my opinion, when Rene says "three fingers' thickness" what he means is the original, uncompressed thickness and that the stuffing is to be quilted down into something *much* less thick--obviously, you couldn't wear a garment that was padded this thickly otherwise. Remember, too, that this book refers to a tournament that was never held; Rene was harking back to his interpretation of tournaments of the older days of chivalry, so take everything here wit that in mind. This was to have been a specialized kind of event where the combatants used blunted swords with thick edges and heavy wooden clubs in a very plaisance-oriented environment, which may have explained his requirement for a padded garment.

Ah, cheers Hugh. I must say I did wonder if three fingers thick was a tad overkill :lol:

Page 1 of 1

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum