why did sabers, cutlasses, etc. supersede straight bladed weapon in the later eras?

i'm sure you could write a book about the topic, but i'm looking for a short, simple and general answer.

thank you.

Let's establish that I am in no way an expert on this subject,but here's a reason.Thinking about this logically,the "later eras" (1750-1900?) seen a steady decline and eventual demise of swords for combat as guns became evermore efficient.One of the last stands of the sword in warfare was in the calvary.It was MUCH easier to acquire the needed momentum for an effective blow from horseback with a curved blade than a straight one.Throughout history,you'll often see that groups who were skilled in horseback engagements(the Arabs,for example) usaully used curved blades,while skilled footsoldiers(such as the Scotts) would most often use a straight blade.Another reason possibly could have to do with the fact that a sword with a curved blade served more usefullness as a tool .I know I didn't deal with the question completely,but I'm only half awake anyways :lol: ;) Hope this gives you a small scrap of insight. :D

| Quote: |

| why did sabers, cutlasses, etc. supersede straight bladed weapon in the later eras? |

They never did, straight bladed weapons continued to be used alongside sabers and other curved blades until the demise of the military use of the sword in the early 20th century.

| Daniel Staberg wrote: | ||

They never did, straight bladed weapons continued to be used alongside sabers and other curved blades until the demise of the military use of the sword in the early 20th century. |

Yep...and the final calvary sword used by the US was a straight sword. Specifically the M1913 designed by Patton. So one could even argue that the straight sword won out over the curved swords even. I wouldn't...but somebody could ;) .

In short, curved blades are great for cutting soft targets. This is mainly because the curve makes them slide through the wound. They are also less likely to snag when performing draw cuts.

On the down side, you need a better angle to strike past the opponents block, and it will slide of hard armour.

However, ANY kind of sword swung with intent will kill a unarmoured man with little difficulty. Which is why there are so many different varieties.

On the down side, you need a better angle to strike past the opponents block, and it will slide of hard armour.

However, ANY kind of sword swung with intent will kill a unarmoured man with little difficulty. Which is why there are so many different varieties.

Um...the Pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry Sword? It was straight and of quite a late provenance. Not to mention that it also had a long heritage stretching through a succession of straight Austrian heavy cavalry swords right to the Walloons and Pappenheimers of the 17th century.

As has already been stated thoroughly already, straight blades never disappeared and are still in use today.

But neither did curved ones. Rather the question should be, why did we stop using swords in war? And the answer is pretty obvious... We didn't. Short swords like tactical wakisashi and O-tantos are being used by some US troops in Irak and Afghanistan today, because iraqi insurgents resort to trying to rush them with blades at times. Not the big swords of old, but still pretty decent cutters with some authority.

The eternal question, is a curved blade a better cutter or not isn't as simple as most think. And does it have to be a better cutter to be a good hand weapon, could it have other desirable or practical qualities?

For one, we see today that sharpness of the blade is what makes a katana cut a tatami well, and also what makes a straight Jian or europeean straight sword cut well, possibly just as well even. Slow motion photography prove that neither blade need to draw to cut properly, nor does a curved blade naturally tend to draw due to it's shape as many believe. Look at James Williams videos with both japanese and europeean blades. Where's the difference?

In gory detail, the curved blade will be easier to dislodge from a dispatched opponents cranium after a cut when riding past on horseback, possibly the curve of a saber also makes it easier and safer to retrieve the blade after a thrust from horseback. Backswords also tend to be easier to learn how to use safely for cutting, and I expect for combat because it's less risk of cutting oneself and you can rest it on an unarmored shoulder without risking injury. Curved blades tend to have surprising thrusting angles also, curving around a guard and still plenty of force.

Also, my personal theory of how a curved blade helps with cutting is because it has a smaller contact area for the force to work into the surface it cuts. So not so much better cutting as more efficiency of the force applied. Or perhaps that is indeed a better cutting ability after all, depends on how you look at it. Other blade shapes may lend themselves to this also, like the flamberge, modern serrated blades. Then there's the saw toothed Tulwars that are both curved and serrated possibly maximizing this to the extreme -if it actually works.

But neither did curved ones. Rather the question should be, why did we stop using swords in war? And the answer is pretty obvious... We didn't. Short swords like tactical wakisashi and O-tantos are being used by some US troops in Irak and Afghanistan today, because iraqi insurgents resort to trying to rush them with blades at times. Not the big swords of old, but still pretty decent cutters with some authority.

The eternal question, is a curved blade a better cutter or not isn't as simple as most think. And does it have to be a better cutter to be a good hand weapon, could it have other desirable or practical qualities?

For one, we see today that sharpness of the blade is what makes a katana cut a tatami well, and also what makes a straight Jian or europeean straight sword cut well, possibly just as well even. Slow motion photography prove that neither blade need to draw to cut properly, nor does a curved blade naturally tend to draw due to it's shape as many believe. Look at James Williams videos with both japanese and europeean blades. Where's the difference?

In gory detail, the curved blade will be easier to dislodge from a dispatched opponents cranium after a cut when riding past on horseback, possibly the curve of a saber also makes it easier and safer to retrieve the blade after a thrust from horseback. Backswords also tend to be easier to learn how to use safely for cutting, and I expect for combat because it's less risk of cutting oneself and you can rest it on an unarmored shoulder without risking injury. Curved blades tend to have surprising thrusting angles also, curving around a guard and still plenty of force.

Also, my personal theory of how a curved blade helps with cutting is because it has a smaller contact area for the force to work into the surface it cuts. So not so much better cutting as more efficiency of the force applied. Or perhaps that is indeed a better cutting ability after all, depends on how you look at it. Other blade shapes may lend themselves to this also, like the flamberge, modern serrated blades. Then there's the saw toothed Tulwars that are both curved and serrated possibly maximizing this to the extreme -if it actually works.

Cutless' were primarily designed for shipboard combat where armour in minimal but so was space. the curved heavy blade allowed quite good cuts with less swing and less chance of getting tangled up in rigging, woodwork and unintended targets (your people). There were still issued to boarding parties in the Second World War and a re sometimes seen on the hips of senior naval NCO's on parade.

Straight blades were never really superseded by curved blades, they just lost prominance was the common soldier switched to a short pike that went BANG (sometimes).

Straight blades were never really superseded by curved blades, they just lost prominance was the common soldier switched to a short pike that went BANG (sometimes).

| Daniel Staberg wrote: | ||

They never did, straight bladed weapons continued to be used alongside sabers and other curved blades until the demise of the military use of the sword in the early 20th century. |

Is WW2 early 20th cent? ;)

Plenty of tests have demonstrated that curved blades aren't any better at cutting than straight ones. Their benefit seems to come from improved manoeuverability in tight situations such as on a ship or when mounted on a horse.

There is a great article, I think on the Sword Forum Int. site, which compared the use of latter day curved and straight cavalry swords, where the first was used more for slashing and the second for stabbing, somewhat like a lance. From what I recall, the general conclusion was that, although the curved blade/slash often produced nasty surface wounds that bled a lot, the straight blade/stab was more likely to produce fatal wounds by damaging important organs and deep arteries. Overall, this analysis suggested that the type of sword used depended on the style of fighting advocated by a particular type of cavalry.

What was missing from the comparison is the heavy chopping and hacking one assumes was more common with earlier two-edged European war-swords - maybe this is what really went out of style.

What was missing from the comparison is the heavy chopping and hacking one assumes was more common with earlier two-edged European war-swords - maybe this is what really went out of style.

| J.D. Crawford wrote: |

| What was missing from the comparison is the heavy chopping and hacking one assumes was more common with earlier two-edged European war-swords - maybe this is what really went out of style. |

I don't think so--the article in question also discusses the Pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry Sword I mentioned above, which has been described by contemporaries as a crude weapon best suited to brutal hacks and chops. If anything, it could have been heavier and clumsier than a good early medieval sword of comparable properties--say, a type X or XI sword with its characteristic long, straight blade and relatively short grip.

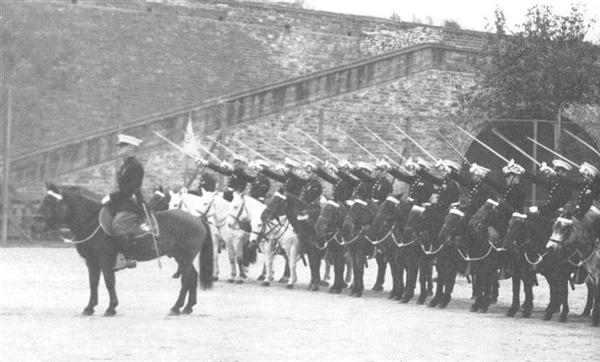

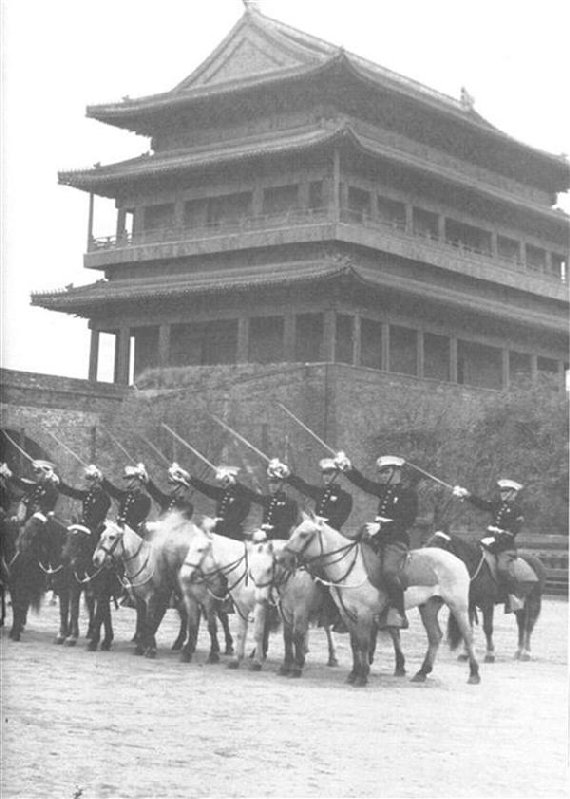

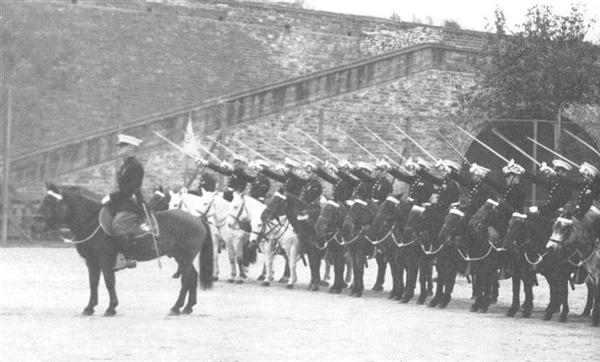

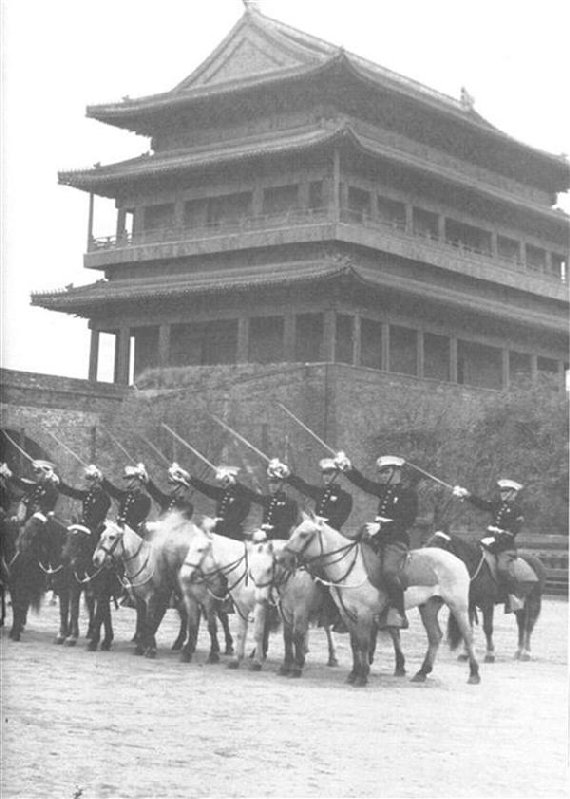

Many cutlass types were quite straight. Many land forces continued to field both straight and curved blades through WWI and into WWII. Patton took one from column A and one from Column B when "designing" what was approved by the U.S. Ordnance in response to European trends dating back some decades to make straight swords the universal fit (and their continuing to field curved blades along with them). U.S. adoption of trends and specific model types during the nineteenth century were generally a couple of decades late in widely using them. the U.S. went backwards in the 20th century to re-issue their mid 19th century sabre (there really was no 1860 but there was a 1906 designation). The Poles carried their 1934 curved blades into the beginning of WWII, with other countries also actually carrying curved swords with mounted troops. Nickel plated Patton swords were being carried and trained with in Peking by the U.S. Horse Marines until displaced by WWII brewing.

The truths, misconceptions, myths and disinformation can easily fill large volumes of text.

Didn't some European hussar troopers simultaneously field both poky straight lance substitutes for the massed charge and curved swords for melee? Oh ya, French lancers with armour used into WWI as well

Cheers

GC

Attachment: 38.99 KB

Attachment: 38.99 KB

Peking Horse Marines

Attachment: 76.05 KB

Attachment: 76.05 KB

Attachment: 106.47 KB

Attachment: 106.47 KB

The chicken and the egg discussion illustrated

The truths, misconceptions, myths and disinformation can easily fill large volumes of text.

Didn't some European hussar troopers simultaneously field both poky straight lance substitutes for the massed charge and curved swords for melee? Oh ya, French lancers with armour used into WWI as well

Cheers

GC

Peking Horse Marines

The chicken and the egg discussion illustrated

| Lafayette C Curtis wrote: | ||

I don't think so--the article in question also discusses the Pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry Sword I mentioned above, which has been described by contemporaries as a crude weapon best suited to brutal hacks and chops. If anything, it could have been heavier and clumsier than a good early medieval sword of comparable properties--say, a type X or XI sword with its characteristic long, straight blade and relatively short grip. |

I stand corrected!

| Lafayette C Curtis wrote: |

|

I don't think so--the article in question also discusses the Pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry Sword I mentioned above, which has been described by contemporaries as a crude weapon best suited to brutal hacks and chops. If anything, it could have been heavier and clumsier than a good early medieval sword of comparable properties--say, a type X or XI sword with its characteristic long, straight blade and relatively short grip. |

Sorry if I'm comign off a bit strong here, but the 1796 American Cavalry saber type happens to be one of my all time favorites.

I suspect those contemporary sources would be people used to rapier fencing only? Anything with some tip weight would feel crude then. I've had friends who are pure rapier fencers handle the light marine saber in my collection say the same about that and to me it feels quite well balanced, well rounded for fast cutting as well as thrusting.

The 1796 is the western version of the indian Tulwar and I've some experience with both. They're a bit of two-in-one, part saber and part light Falchion and if you're just used to that it feels like the extension of your arm. Quick and lively but still packs a mighty cut. Tip control was excellent especially with the odd looking indian gavel, I've seen modern fencer handles with a similar design. Yes it can do "crude" hacks and chops very well, but it's also a more than adequate thruster.

To get an idea of how the 1796 Cavalry saber works and enjoy a bit of drama one can look at the Cold Steel videos with their reproduction.

| Johan Gemvik wrote: | ||

Sorry if I'm comign off a bit strong here, but the 1796 American Cavalry saber type happens to be one of my all time favorites. I suspect those contemporary sources would be people used to rapier fencing only? Anything with some tip weight would feel crude then. I've had friends who are pure rapier fencers handle the light marine saber in my collection say the same about that and to me it feels quite well balanced, well rounded for fast cutting as well as thrusting. The 1796 is the western version of the indian Tulwar and I've some experience with both. They're a bit of two-in-one, part saber and part light Falchion and if you're just used to that it feels like the extension of your arm. Quick and lively but still packs a mighty cut. Tip control was excellent especially with the odd looking indian gavel, I've seen modern fencer handles with a similar design. Yes it can do "crude" hacks and chops very well, but it's also a more than adequate thruster. To get an idea of how the 1796 Cavalry saber works and enjoy a bit of drama one can look at the Cold Steel videos with their reproduction. |

Hi Johan,

I am a bit puzzled by your post and the differences between truths and what becomes confused. The two 1796 patterns being discussed previously in this thread are both British patterns and written of at length in the above linked article penned by Martin Read. Please do take a long read of that page for a good start in understanding more about history instead of Cold Steel and their poorly thought out ad copy. The article linked and written by Read is quite well done and researched. Lynn Thompson and his Cold Steel ad copy is not, despite his "wow" videos. Many of his sword designations are simply wrong headed, such as his Napoleonic 1830 sabre. Think about that ;) Really, think about that ;) ?8^)~

The British 1796 light cavalry sabre is absolutely not based on the Indian Tulwar

http://swordforum.com/articles/ams/cavalrycombat.php

American use of the British patterns went hand in hand with both the 1796 British LC sabre and the straight British 1796 heavy. However, there were contemporary contracts by makers such as Rose and Starr that grew in American arms use. I do have a couple photo examples I can share of both an Americanized sabre and the straight heavy blade but picking up a couple of books regarding American sword growth and use may be of great benefit to you. Peterson's American Sword, 1775 to 1945 is still considered a good basic bible you can pick up inexpensively and while dated, as is Neumann's Swords and Blades of the American Revolution are two great beginnings for not just American swords but those appearing from England and the European continent. Scandinavia as well fielded what is essentially the British 1796 LC as well.

Anyway, those two types used in America but of British origin. Another great picture book and quite well cataloged is the Medicus Collection of swords used in America over a couple of centuries. That by the younger Stuart Mowbray and Norm Flayderman. www.manatarmsbooks.com/

It is just sad to read the bad information repeated time and again without a thought about the real information just a click away.

Cheers

GC

American grafitti

Not as pretty an eagle as the Mowbray book example but representative of an Americanized British 1796 heavy cavalry sword.

There are also some excellent articles on the P1796 LC swords (and photos) available at www.swordsandpistols.co.uk

Last edited by Jonathan Hopkins on Fri 12 Nov, 2010 5:55 pm; edited 1 time in total

Another pair of thought from the late 1780s but patterns that went back a quarter century or more before that. Edit to add that some may note a trend in my own collecting and the thoughts of thrust vs cut over the decades and centuries :lol:

Cheers

GC

Attachment: 72.25 KB

Attachment: 72.25 KB

Two British pattern infantry types. One straight, one curved.

Cheers

GC

Two British pattern infantry types. One straight, one curved.

Last edited by Glen A Cleeton on Fri 12 Nov, 2010 5:01 pm; edited 2 times in total

Move forward again to the 19th century and we have here a pair from American use of quite similar proportion and purpose.

Attachment: 123.4 KB

Attachment: 123.4 KB

Berger sabre and Spies (New York, see Wolfe) retail spadroon both common patterns but of Solingen and Austrian make

Berger sabre and Spies (New York, see Wolfe) retail spadroon both common patterns but of Solingen and Austrian make

As stated they didn’t, but they did ‘come back into fashion’ over how much usage curved blades had been in use a few hundred years earlier. I think your better question is why did Europe eventually adopt a curved sword after so many years of using mostly strait blades?

My opinion is definitely armor. Europe was fond of very heavy armor, when compared with what the rest of the world was using, cutting chain mail is pretty useless, and cutting plate armor is even more futile. By the time Europe moved to adopt the Sabre they had dropped the heavy armor, which makes cutting from horseback a much more viable option. The foot soldiers would adopt a blade that fit their style of fighting, but some preferred a more curvy (sometimes shorter) blade for use in close quarters of a tight fight.

Here’s the article on infantry swords - http://swordforum.com/articles/ams/1776-1815britishinfantry.php

Why did they come in fashion for officers to use when directing the troops, because they just look cool.

My opinion is definitely armor. Europe was fond of very heavy armor, when compared with what the rest of the world was using, cutting chain mail is pretty useless, and cutting plate armor is even more futile. By the time Europe moved to adopt the Sabre they had dropped the heavy armor, which makes cutting from horseback a much more viable option. The foot soldiers would adopt a blade that fit their style of fighting, but some preferred a more curvy (sometimes shorter) blade for use in close quarters of a tight fight.

Here’s the article on infantry swords - http://swordforum.com/articles/ams/1776-1815britishinfantry.php

Why did they come in fashion for officers to use when directing the troops, because they just look cool.

Page 1 of 3

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum