Originating from John Jacob of the Scinde Horse, the scroll hilt (or acanthus hilt) is best known for its brass incarnation in the form of the British Pattern 1857 Royal Engineers Officer’s Sword. But well before 1857 a steel version was favored by officers serving in India, and continued to be produced for discerning officers of both the British and Indian Armies who wanted good fighting swords. My sword, serial number 13539, was made in 1865 for Captain Richard Topham of the 16th Bengal Cavalry. The 1 lb. 14 oz. sword is an excellent example of a weapon intended for service. The steel guard is engraved with an acanthus leaf design. The rest of the weapon is rather Spartan in design. Aside from the standard Wilkinson Pall Mall, and the proof disc, the only blade decoration is the officer’s family crest. The rest of the 34 ¼” blade is plain, and has been sharpened for service. The sharpening begins 8” from the guard and continues to the tip, while almost 7” of the false edge has been sharpened. The scabbard is steel with a German silver mouth, and the inside is lined with wood.

Richard Topham’s first commission was as an ensign in the Royal Lancashire Militia (1st March, 1855). Soon thereafter, he was promoted lieutenant (June, 1855). In July of the same year, he purchased his first regular army commission as a cornet in the 4th (The Queen’s Own) Regiment of Light Dragoons. Less than one year later, on 14 March 1856, Topham was promoted lieutenant (without purchase). At some point in 1857 he transferred top the 7th (The Queen’s Own) Regiment of Light Dragoons (Hussars) and embarked for service in India. Topham served with distinction during the Indian Mutiny (also known as India's First War of Independence, the Great Rebellion, the Indian Rebellion, the Revolt of 1857, the Uprising of 1857 and the Sepoy Mutiny). The Hart’s List for 1860 records:

| Quote: |

| Lieut. Topham served in the Indian campaign from Feb. 1858 to March 1859 and was present at the repulse of the enemy’s attack on the Alumbagh, siege and capture of Lucknow, affairs of Barree (wounded) and Sirsee, action of Nawabgunge (contused), occupation of Fyzabad, passage of the Goomtee at Sultanpore, throughout the Byswarra campaign, including the affairs at Kandoo Nuddee, Paleeghat, and Hyderghur, and pursuit of Benhi Madhu's force to the Goomtee; also the Trans-Gogra campaign, including the affair near Churda and pursuit, taking the fort of Meejeedia , attack on Bankee with pursuit to Raptee, advance it to Nepaul and affair at Sitkaghat (twice mentioned in despatches, Medal and Clasp). |

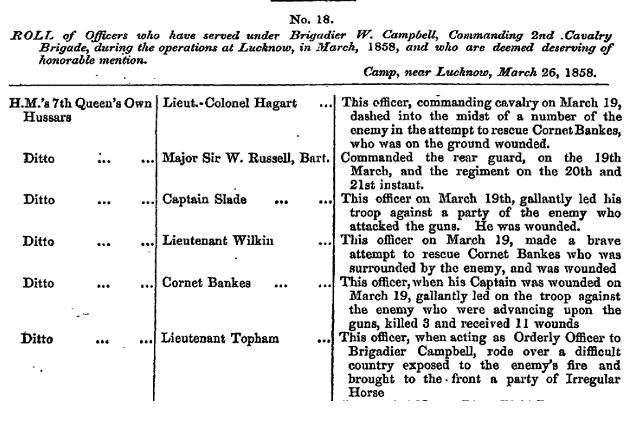

Topham’s mentions in dispatches are recorded in the London Gazette:

| Gazette Issue 22143 published on the 25 May 1858 wrote: |

|

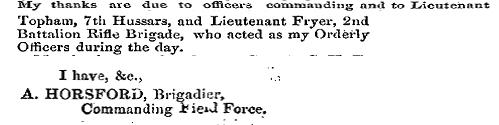

| Gazette Issue 22259 published on the 5 May 1859 wrote: |

|

And his actions in the field are recorded in several texts, including The Life of General Sir Hope Grant with selections from his correspondence:

| General Sir Hope Grant wrote: |

| On the 13th April we marched at daybreak, but had scarcely gone three miles on our way when I heard the advanced - guard commence firing. The road, or rather track, had been very bad, and I had remained behind to see the heavy guns brought across a nullah. I immediately galloped to the front, and found that a strong cavalry picket of the enemy had attacked our advanced- guard—had surrounded a troop of Wales' Horse, wounding one of the officers, Prendergast1 — and would have taken the two guns which were with it,—when they suddenly perceived a squadron of the 7th Hussars, which the dust had hitherto prevented them from seeing, ready to charge them, whereupon they wheeled about and galloped off. When I reached the scene of the conflict I saw this hostile force, which now amounted to some thousand men, working round our right flank, evidently bent on attacking our baggage, which extended over a line of nearly three miles. I instantly brought up 300 cavalry and two of Mackinnon's guns to protect our flank, and fired several shots at them, but without effect. In addition to our rear-guard, I ordered the Bengal Fusiliers to cover our right flank. I sent a troop of the 7th Hussars to patrol along both flanks, and another squadron to watch the movements of the sowars. The enemy came round in rear of a village, and were in the act of charging upon our baggage when the troop of the 7th Hussars, who were ready prepared for them, dashed down and galloped through them, putting them .to flight and sabring many of their number. Captain Topham, who commanded the troop, and who had run a native officer through the body, was wounded by a lance. He had two men mortally, and six men slightly, wounded. A little after, another body of the rebels charged down upon our baggage, but were met by two companies of the Bengal Fusiliers, who poured a volley into them when within 30 yards distant, which rolled a number in the dust. Thereupon they desisted from further attacks, and retreated as quickly as possible. The infantry were then ordered to advance. The enemy occupied a village on a hill in front of us, at the base of which a stream flowed. Large columns were posted on both sides of this valley. I threw out the Rifle brigade in skirmishing order, supported by the 5th Punjab corps. The main line in rear advanced close up to the village under a heavy fire and stormed it gallantly, capturing two colours. We afterwards advanced and took the higher ground, the rebels bolting without firing a shot. The cowardly fellows might, with a little resolution, have defended the position. |

Following the Mutiny, Topham remained in India and was attached as commandant to the 16th Bengal Cavalry in 1860. Topham purchased his captaincy 16 October 1863. In 1865 Topham officially transferred to the Bengal Staff Corps, and the occasion merited the purchase of his scroll hilt sword. He continued to serve as commandant of the 16th Bengal Cavalry—a position he would keep for the remainder of his career.

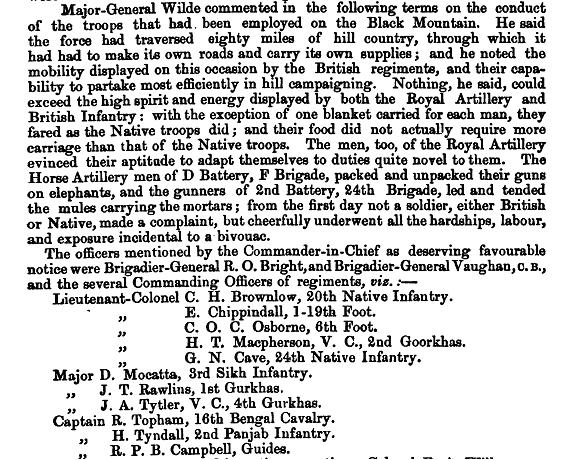

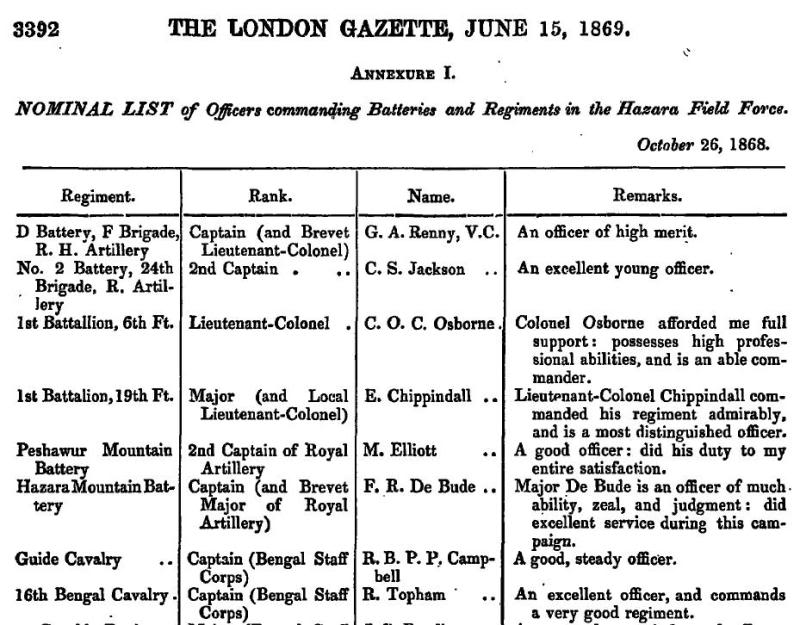

Topham’s next and final active service was during the Black Mountain (sometimes called 1st Hazara) Expedition of 1868. He would have carried his new scroll hilt during this campaign. Topham ably commanded his regiment and was mentioned in despatches for his service (William Henry Paget , A Record of the Expeditions Undertaken Against the North-West Frontier Tribes):

He received further commendations, as well:

| Quote: |

|

The remainder of Topham’s career appears to have been relatively quiet. He continued to command the 16th Bengal Cavalry:

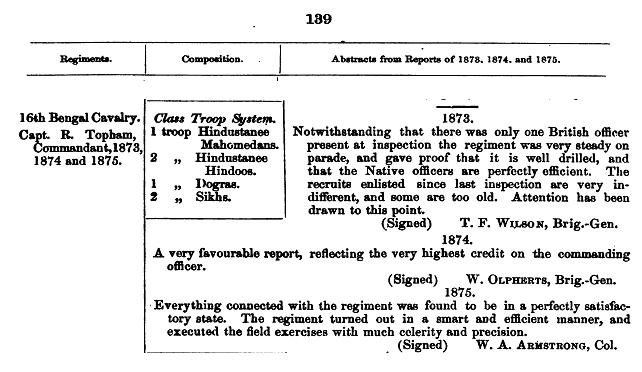

| Parliamentary Papers, 1877 wrote: |

|

Topham was promoted Major on 27 July 1875. Sadly, he died the following year while his regiment was station in Bareilly. I have not been able to determine his cause of death, but cholera seems a likely suspect as there was an outbreak in Bareilly just before he died.

Based on the regiments with whom Topham served, he was probably quite familiar with special patterns and may have owned several throughout his career. The 4th Light Dragoons carried a variation of the scroll hilt which feature their regimental device (see Stephen Wood’s “Swords for the Crimea: some Scottish officers’ swords manufactured for Britain’s war with Russia 1854-56”, Journal of the Arms and Armour Society, London, Vol. XVIII, No. 3, pp 115-135.) In addition to the individual flair of his previous British regiments, Topham would have been influenced by the fashion and preferences of officers of the HEIC and Indian Armies (see Graeme Rimer’s “The swords of John Jacob”, Royal Armouries Year Book 2, 1997), which probably led to the purchase of his final fighting sword.