On the Golden Section and its use in design and engineering can be written volumes. It is difficult to address this in a good way in short post. One alwys runs the risk of creating new "truths" that are actually just one aspect or version of what is possible.

I am still working with this hypothesis. There certainly are trends in how this is applied in swords, but I feel reluctant to go into too much detail at this stage. I have hopes to publish these ideas with thorough ilustrations and examples: it is not a very good idea to present the work while it is still only halfway done.

I do not intend to hide this under a blanket, but I would like to have opportunity to make a full presentation in due time.

The presentation I did during the "Swordfest" at Albion was using the sword of Svante Nilsson as example.

It was actually this sword that put me on the track of finding ways to analyze swords in the aspect of the Golden Section.

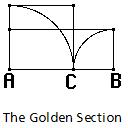

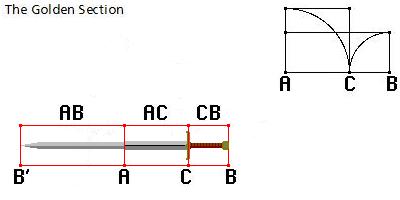

One day some years ago I was trying to find a way to implement harmonic proportions in sword design just as it it used in typography and sat scribbling witth a pencil in a sketch book. To start with I drew a line on a peice of paper to represent the length of the blade. I divided this in eight parts resutling in a module to be used as a "building block"(8 being a number in the fibonacci series). I then could use 1, 2, 3, and 5 to multiply the module with as all these belong to the Fibonacci series. This is a rather basic way to use the tool but I wanted to keep it simple to begin with.

I tried to have the hilt 3 times the module and the guard two times the module.

The resulting pencil cross on the paper started to look strangely familiar...

Half the module was assigned to blade width and width and length of pommel and I now saw the sword of Svante Nilsson emerge from the pencil lines on the paper...

I double checked the measurement of the sword as I had noted them and found a high degree of correspondence. The deifference was less than a milimeter in many cases and well within acceptable variation given that the sword was not made with a precision caliper or pocket calculator at hand.

Going further I found interesting correspondances in how the

distal taper varied along the blade and how these sections of the blade related to each other.

Next I started to look through other swords I had documented and saw that you could see harmonic proportions being applied in many aspects. Especially in how blade width , thickness and distal taper varied rythmically in different swords, but also in over all proportions of hilt components and outline of the blade.

Interestingly it seems that the use of harmonic proportions in the shaping of a blade will have effects in the placing of nodes, pivot points and resonance. This has a direct effect on performance and handling.

Harmonic proportions therefore seem to have an effect not only on the aesthetic aspects of a sword, but also its performance.

It is to be likened with how many musical insteuments are built according to harmonic proportions, to make the most of their accoustic potential.

In the case of swords the desired effect is the opposite: you want to minimize the influence of vibrations.

I hope this short text will give you an idea of the scope of this topic: Harmonic proportions can influence many different aspects of the sword and can also be a tool in our understanding of their functional principles.

To make a more thorough presentation of this I would have to write a much longer text and provide illustrations and examples from historical swords. This will have to wait till a possible future publication.

So how much of this was ancient swordsmiths aware of?

It would have varied of course. You need not have theoretical schooling in these matters to be able to do work that express harmonic propotions. It only takes a good eye and a developed understanding of form.

I would not be surpriced if cutlers in urban areas who socialized with masons, artisans or artists of various kinds knew about and discussed these ideas. It is not unreasonable to assume cutlers defined some aspects of the blades they ordered from blade smiths.

Likewise, I think that blade smiths through history (a few or many?) would have developed a theoretical understanding of proportions. It is reasonable to work according to rules of thumb and well defined processes when producing volumes of blades to set standards. Before the blade is shaped the billet is drawn out to a bar of specific taper and cross setction. This is then given the correct crosss section and possibly a fuller. The proto blank need to have the correct distribution of mass for the final blade to have the correct balance. If many blades are forged in a series, which would have been normal, then it makes good sense to designate the proportions of the proto-blank. Those proportions would carry through in the finished blade even after grinding.

This is actually an important aspect in my design work for Albion: My blade designs are much like the forged blank that the blade smith would have sent to the grinder. That semi finished blade need to have the right proportions or the sword willl not have the correct heft or perfomance.

Harmonic proportions is a design tool that is of great help in acheiving swords that have the same heft and feel as their historical counterparts.