Posts: 14 Location: Turku, Finland

Mon 25 Aug, 2008 9:43 am

Thanks for your comments, Jeremy.

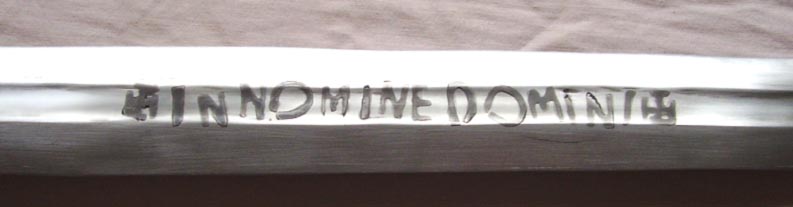

To begin with, there are numerous disc-pommeled swords in Finland dating to the so-called Crusade period in Finnish chronology, i.e. circa 1050-1150 AD. Some of these swords are most likely a bit later. Many of these types of swords bear iron inlays, most often incomprehensible series of letters, perhaps illiterate versions of INNOMINEDOMINI or something else. As I am currently x-raying Finnish swords, these kinds of small inlays appear continually, and so their amount in the Finnish material cannot be accurately stated. By now there are around twenty swords bearing small iron/steel inlays, some of which are uncertain due to the very bad preservation of the finds.

What is noteworthy, is the material of the inlays. A common assumption is that the inlays are iron while the blade or its surface is steel. In Finnish material this is true in some rare cases. Most often though the inlays appear darker than the blade when etched with Nital or some other mild acid. Moreover, the inlays seem to be corroded more than the blade. Both these observations indicate that either the material of the inlays has a greater carbon content than the blade (or the surface of the fuller to be more precise), or there is some other element present in the blade material, which prevents corrosion. In any case accurate analyses are needed.

In my personal opinion the steel inlays make more sense than iron inlays. When etched the steel inlays appear darker against the polished blade. If blade with iron inlays is etched, the inlays will appear lighter while the surface of the blade etches darker and deeper. In this case the bottom (or the surface) of the fuller is hard to re-polish after the etch, because the inlays will also be polished and the contrast is then destroyed. Of course the welding seams around the edges of the inlaid letters will become more visible due to etching.

A note should also be made about these small inlays executed with pattern-welded material. So far two of these are found in Finnish material, both unpublished since the materials of the inlays have not been considered noteworthy. The patterns in the inlays are VERY fine, but can be observed with bare eyes.

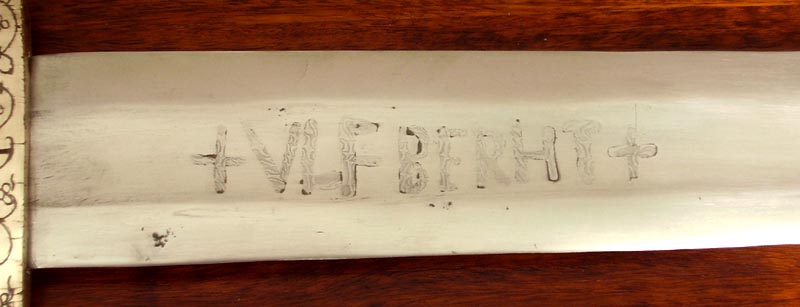

I have once tried to make a sword with GICELINMEFECIT on one side, and INNOMINEDOMINI on the other. The material of the blade was modern carbon steel with a carbon content of 0.5 %, while the inlays were almost pure iron. I welded the inlays straight on the surface of the blade blank, just like I have experimented with ULFBERHTs. The problem was that the inlays did not get deep enough – just as with ULFBERHTs too. Since the inlays were also smaller in scale, they were more easily ground off while finishing the fuller. Also the problem of etching struck me while finishing the blade.

Just as with bigger inlays, the smaller ones should also be sunk deeper in the blade. This in turn can be achieved with multiple ways. One way is to carve the grooves for the letters. This is functional, although very laborious. Alternatively, the grooves could be struck with different punches. This I have done once to create an ULFBERHT-inscription, quite successfully. This also corresponds to archaeological finds, since the structure of the blade is sharply bent underneath the inlays, rather than cut. Still it should be mentioned that inlays of three blades have been analysed, so alternative techniques must have been in use… And none of these analysed inlays were the smaller ones, but big pattern-welded inlays.

Recently I had a commission to make a GICELINMEFECIT-sword. I will intend to sink the inlays by hammering them cold against the hot blade before welding them. At least this technique worked the best for bigger inlays. It is also the fastest one. Still it is yet to be seen, if the smaller inlays can be hammered into the blade before they heat up too much on the glowing blade…

And finally some overall pictures of swords:

Attachment: 17.78 KB

Attachment: 17.78 KB

The Petersen type K sword, model from the famous Ballinderry find.

Attachment: 24.58 KB

Attachment: 24.58 KB

The INGELRIIMEFECIT blade. Still without a hilt.

Attachment: 60.83 KB

Attachment: 60.83 KB

A Mannheim-type sword with INGELRII inscription. [ Download ]