Hello Everybody!

I know about the wootz evolution in India but I would like to know when there is the first evidence of pattern welding in europe (or other areas)?

Thanks for any information

Herbert

| Herbert Schmidt wrote: |

| Hello Everybody!

I know about the wootz evolution in India but I would like to know when there is the first evidence of pattern welding in europe (or other areas)? Thanks for any information Herbert |

Dear Herbert,

Pattern welding began with the Hallstatt Iron Age in Central Europe, Southern Germany, Switzerland, Hungary and the Balkans. It Was contemporary with the Greek Iron Age but no examples of 10-7th Century swords are available for study that I know of. I have Celtic Naue II iron swords that are available for study if anyone is interested. In Thrace they were given the title of Xiphos, I have one of these.

I have books on Celtic LaTene swords if you are interested in doing further research on the metallurgy.

Hello John,

Excuse my stupid question, but how do you know that there was pattern welding in the Hallstadt period when no examples exist? Or did I get you wrong here?

Anyway, thank you very much for your info - seems like you have a tremendous collection!

Herbert

Excuse my stupid question, but how do you know that there was pattern welding in the Hallstadt period when no examples exist? Or did I get you wrong here?

Anyway, thank you very much for your info - seems like you have a tremendous collection!

Herbert

| John Piscopo wrote: | ||

Dear Herbert, Pattern welding began with the Hallstatt Iron Age in Central Europe, Southern Germany, Switzerland, Hungary and the Balkans. It Was contemporary with the Greek Iron Age but no examples of 10-7th Century swords are available for study that I know of. I have Celtic Naue II iron swords that are available for study if anyone is interested. In Thrace they were given the title of Xiphos, I have one of these. I have books on Celtic LaTene swords if you are interested in doing further research on the metallurgy. |

Dear John,

I whish I lived more close to you, as I´d love to take you up on that offer! Very generous of you.

I am presently collecting material on early iron age. Finds are rare, unfortunately, and those that are are usually just sword shaped lengths of rust.

In my part of Europe we generally do not get any La Tène swords and there are no finds, to my knowledge of Naue type iron swords. There was iron and steel production established already in the 7th or 6th C BC, but no weaponry is preserved from that time. (It might be telling that the last period(s) of the brinze age is low in finds of weapons and tools)

We do get a particular type of single edged sword/knife that is interesting, even if it is not very beautiful at first glance...

This was found in the Danish Hjorsrings find (from around 350 BC) but there are other finds that are earlier. One swedish find is from around 500 BC (I think).

I´d love to see what type of constrction was used in the early Naue type iron swords. Any traces of wild "pattern" or traces of construction techniques would be very interesting to see.

Herbert, as an example for you: below is a photo from the prehistorical museum in Munich, showing a La Tène sword from around 300-200 BC. The patternwelding is very evident on this one. Note that the edges are *not* patternwelded, only the core.

Peter, thanks a lot for the foto! Most interesting. Apparently the smithing technique was already high in those ages. What would be interesting also would be some metallurgical facts regarding composition of the steel, the alloys they used and what percentage they achieved of the key alloys. In short I am interested when the first good smithing started, capable of producing high quality weapons and tools.

Nearby where I live on the Lake of Constance there is a recreated village of "Pfahlbauten" which covers a settlement from 4000-850 b.c. and there are already quite impressive works (although not steel). It is worth a visit! http://www.pfahlbauten.de/index.htm

Thanks a lot

Herbert

By the way, Peter, your sword performs and handles like a dream! Thanks again for your superior work. I will be missing you in Solingen this year!

Nearby where I live on the Lake of Constance there is a recreated village of "Pfahlbauten" which covers a settlement from 4000-850 b.c. and there are already quite impressive works (although not steel). It is worth a visit! http://www.pfahlbauten.de/index.htm

Thanks a lot

Herbert

By the way, Peter, your sword performs and handles like a dream! Thanks again for your superior work. I will be missing you in Solingen this year!

Apparently the smithing technique was already high in those ages. What would be interesting also would be some metallurgical facts regarding composition of the steel, the alloys they used and what percentage they achieved of the key alloys. In short I am interested when the first good smithing started, capable of producing high quality weapons and tools.

Dear Herbert,

Pattern welding is the natural result of forging blades from small billets or ingots of bloomery iron, which was the technoloty in use during all Iron Age I cultures. They could not get the metal high enough to melt until they adopted the large bellows used to force air through the charcoal to achieve high temperatures, and in some cases coal. The iron billets would have to be hammered repeatedlyat red hot, reheated and hammered again to remove the slag and impurities, then several ingots would have to be hammer welded together to have enough metal to form a sword. I have several books that study this process in LaTene Era swords but Iron Age I Hallstatt sword have not been studied for their metallurgical construction, at least as far as I know about.

It would be a greater discovery to learn that these early swords were not hammer forged and welded rather than that they were, that would imply a much better technology than existed in Iron Age I.

Dear Herbert,

Pattern welding is the natural result of forging blades from small billets or ingots of bloomery iron, which was the technoloty in use during all Iron Age I cultures. They could not get the metal high enough to melt until they adopted the large bellows used to force air through the charcoal to achieve high temperatures, and in some cases coal. The iron billets would have to be hammered repeatedlyat red hot, reheated and hammered again to remove the slag and impurities, then several ingots would have to be hammer welded together to have enough metal to form a sword. I have several books that study this process in LaTene Era swords but Iron Age I Hallstatt sword have not been studied for their metallurgical construction, at least as far as I know about.

It would be a greater discovery to learn that these early swords were not hammer forged and welded rather than that they were, that would imply a much better technology than existed in Iron Age I.

Hello John,

So far I have only found and read The Celtic Sword and Early Irish Ironworking and I was wondering what other books you would recommend on the subject of metallurgy or even just more general swords of the La Tene.

I finally had the time to get a yahoo id and sign up to your group and check out the photos of your collection. Your La Tenes jumped out first thing as being very nice. I remember watching your british one with the bronze pommel piece sell on ebay wishing that I would have had the money to buy it just because the bronze piece was so different. Always wanted to come up with a hilt design that would work with that sword, but never come up with one that I though worked well. The large knives above the la tenes, are those germanic in origin?

Thanks

Shane

So far I have only found and read The Celtic Sword and Early Irish Ironworking and I was wondering what other books you would recommend on the subject of metallurgy or even just more general swords of the La Tene.

I finally had the time to get a yahoo id and sign up to your group and check out the photos of your collection. Your La Tenes jumped out first thing as being very nice. I remember watching your british one with the bronze pommel piece sell on ebay wishing that I would have had the money to buy it just because the bronze piece was so different. Always wanted to come up with a hilt design that would work with that sword, but never come up with one that I though worked well. The large knives above the la tenes, are those germanic in origin?

Thanks

Shane

Hi Peter,

You wrote:

Was it common for the edges to be patternwelded? I had always assumed it was normally just the core-- but my assumptions were just that... assumptions (I plead ignorance).

David

You wrote:

| Quote: |

| The patternwelding is very evident on this one. Note that the edges are *not* patternwelded, only the core. |

Was it common for the edges to be patternwelded? I had always assumed it was normally just the core-- but my assumptions were just that... assumptions (I plead ignorance).

David

Hi All…

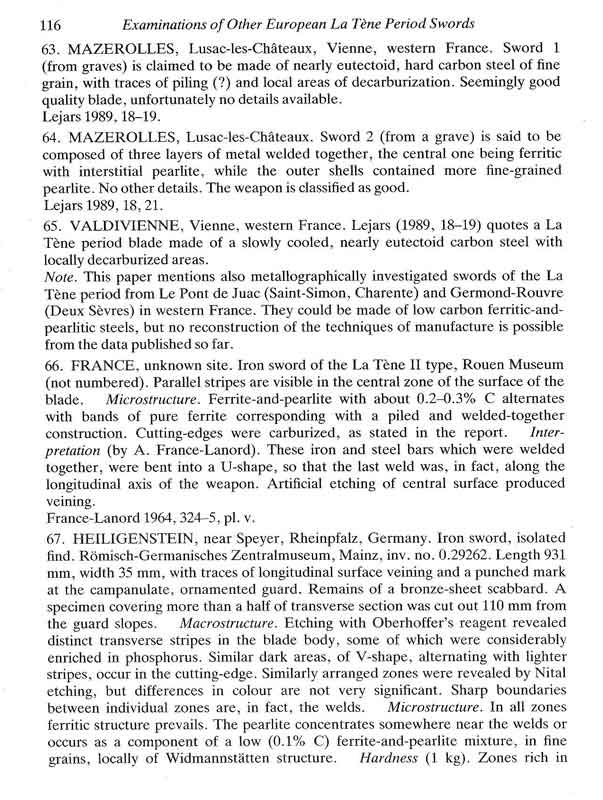

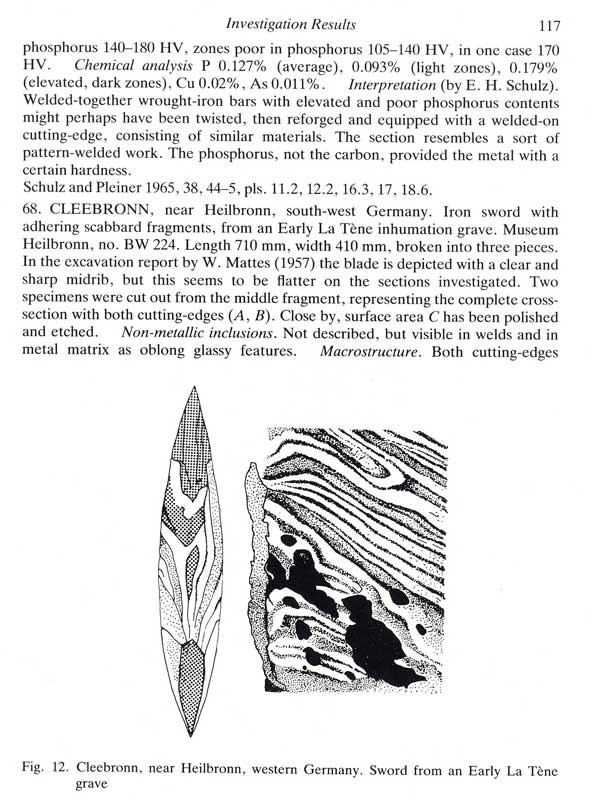

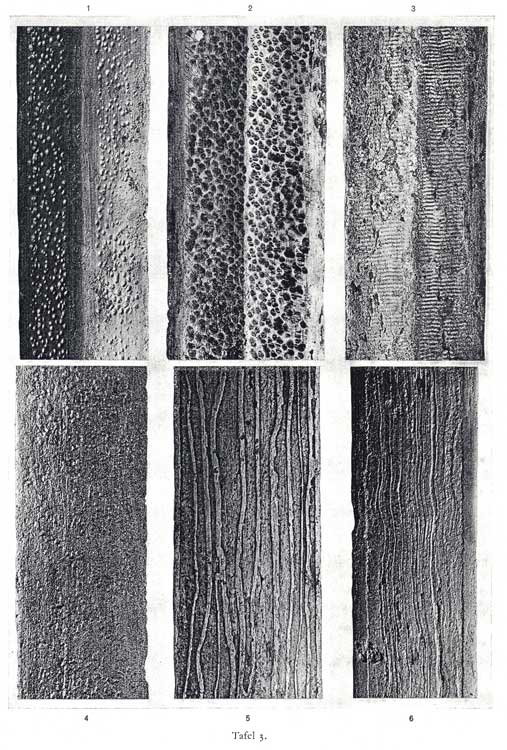

I really had not intended on posting on this thread since I am a real novice at this stuff… but then I found some copies I made of figures in an article I read about two years ago. I had only skimmed this article (on early Iron age metallurgy ) as I was researching the possibility of a pattern-welded double-fullered LaTene blade. I thought that would be a fine looking piece of steel. So when I found some stray figures I had Xeroxed from this article, I thought I would share them with you.

I didn’t remember much about the article except that these earliest composite blades were a very primitive form of proto pattern-welding called a “piled structure.” There really was not much of a pattern to it at all… rather it seemed to be a bundled of thin rods or wires that were welded to varying degrees during the forging process. Later piled LaTene blades, in the fourth century B.C., had a longitudinal core (as the pic that Peter posted in this thread). However, in these earlier blades, these bundles ran at odd diagonals across the blade.

[To reproduce this “piled” look in my LaTene blade, I had a local bladesmith forge me a blade blank out of cable Damascus. He used a large single cable to produce a look somewhat similar to this diagonal piled structure.]

Here are two pages that I saved out of the catalogue of blade descriptions at the end of the article. I think I copied these descriptions because they addressed this issue of proto pattern welding. In the case of the Cleebronn blade, the author shows sketches of etchings on the blade surface and cross section. The welds are defined by slag inclusions. Evidently I didn’t think the next page, discussing the cutting edges, was important…sorry. (see my next reply and I will try to remember what it said about the cutting edges.)

ks

Attachment: 80.76 KB

Attachment: 80.76 KB

Early Iron Age Metalurgy Blade Descriptions

Attachment: 85.31 KB

Attachment: 85.31 KB

Early Iron Age Piled Structure

I really had not intended on posting on this thread since I am a real novice at this stuff… but then I found some copies I made of figures in an article I read about two years ago. I had only skimmed this article (on early Iron age metallurgy ) as I was researching the possibility of a pattern-welded double-fullered LaTene blade. I thought that would be a fine looking piece of steel. So when I found some stray figures I had Xeroxed from this article, I thought I would share them with you.

I didn’t remember much about the article except that these earliest composite blades were a very primitive form of proto pattern-welding called a “piled structure.” There really was not much of a pattern to it at all… rather it seemed to be a bundled of thin rods or wires that were welded to varying degrees during the forging process. Later piled LaTene blades, in the fourth century B.C., had a longitudinal core (as the pic that Peter posted in this thread). However, in these earlier blades, these bundles ran at odd diagonals across the blade.

[To reproduce this “piled” look in my LaTene blade, I had a local bladesmith forge me a blade blank out of cable Damascus. He used a large single cable to produce a look somewhat similar to this diagonal piled structure.]

Here are two pages that I saved out of the catalogue of blade descriptions at the end of the article. I think I copied these descriptions because they addressed this issue of proto pattern welding. In the case of the Cleebronn blade, the author shows sketches of etchings on the blade surface and cross section. The welds are defined by slag inclusions. Evidently I didn’t think the next page, discussing the cutting edges, was important…sorry. (see my next reply and I will try to remember what it said about the cutting edges.)

ks

Early Iron Age Metalurgy Blade Descriptions

Early Iron Age Piled Structure

Last edited by Kirk Lee Spencer on Sun 25 Apr, 2004 4:23 pm; edited 1 time in total

(Here is what I remember about the cutting edges welded onto these piled structure cores.) It would be reasonable to assume that these applied edges would be high quality steel, yet, if I remember right, the edges were not much better than the core, in some cases worse. In a instances one edge of the blade would have a relatively high quality edge but the other would be really poor. I remember two theories offered for this circumstance:

1.The smiths were just guessing. In this early stage they really had know idea which rods were good quality steel and which were softer iron, so it was sort of a hit or miss proposition.

2.The smiths really did know which rods were better steel and made one side of the blade with good steel for precision cuts and the other with poorer steel for just banging around. In this case the owner needed to know which side was which. This theory seemed strange, however they used the fact that there are a few LaTene blades, which have very assymetrical shoulders. The suggestion was that the lost (or never made) hilt components would have been curved in such a way to suggest which edge was which.

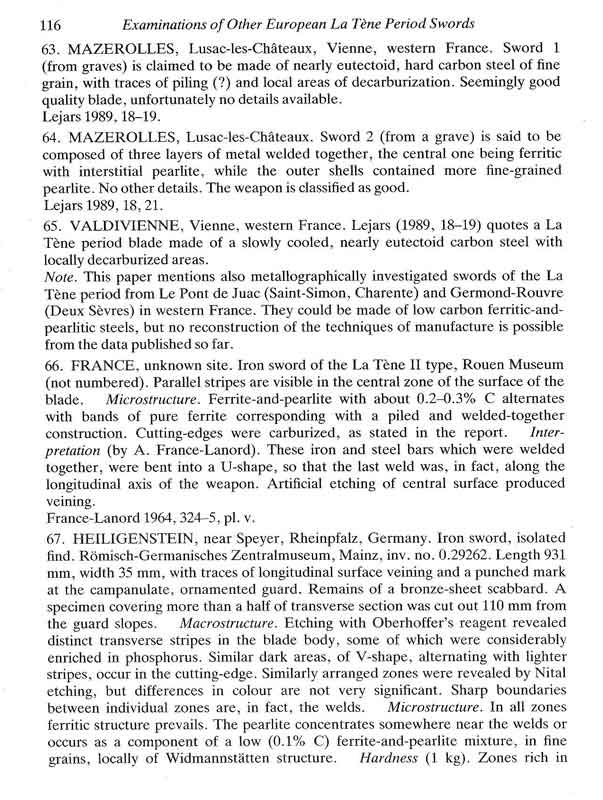

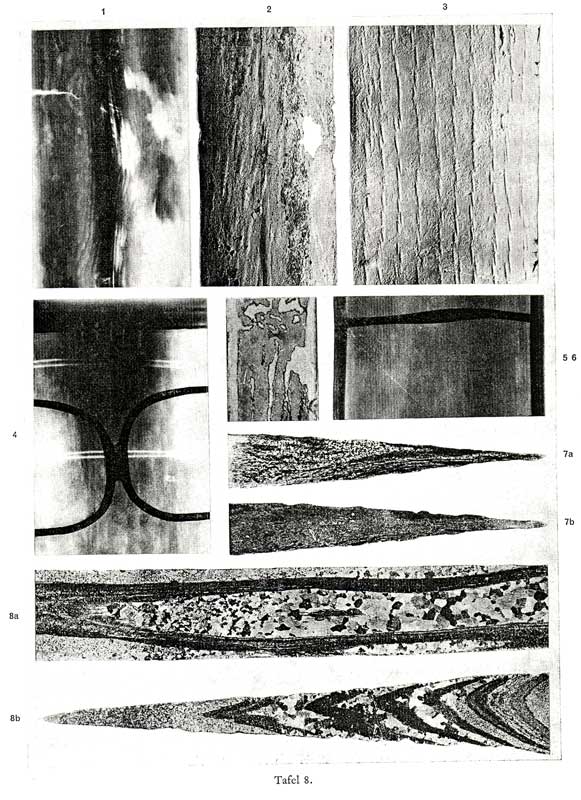

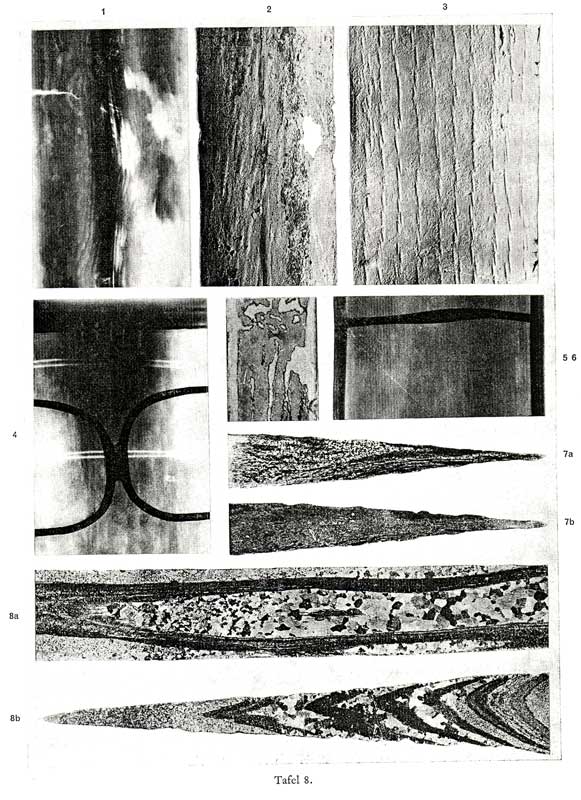

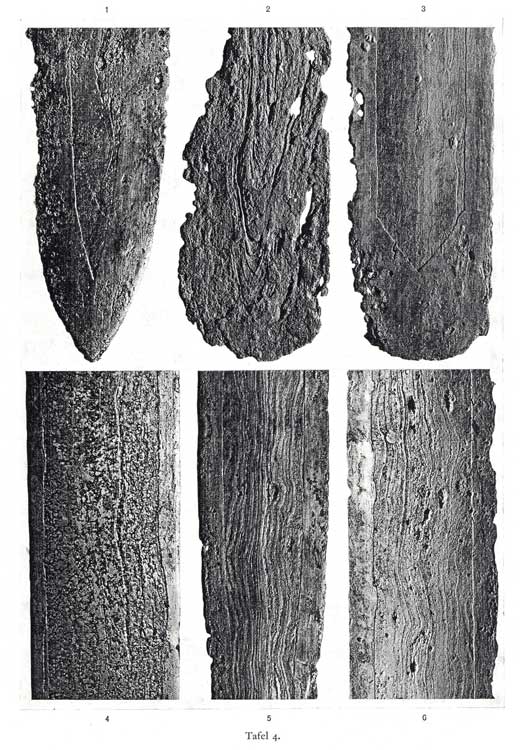

Here are photomicrographs of some LaTene blades from a German monograph. I would love to tell you about them… but I can’t read German… sorry. The bottom is clearly a cross-section of the blade showing the piled structure. I think the image above it is a longitudinal section of the blade.

ks

Attachment: 96.63 KB

Attachment: 96.63 KB

LaTene Blade Cross Section

1.The smiths were just guessing. In this early stage they really had know idea which rods were good quality steel and which were softer iron, so it was sort of a hit or miss proposition.

2.The smiths really did know which rods were better steel and made one side of the blade with good steel for precision cuts and the other with poorer steel for just banging around. In this case the owner needed to know which side was which. This theory seemed strange, however they used the fact that there are a few LaTene blades, which have very assymetrical shoulders. The suggestion was that the lost (or never made) hilt components would have been curved in such a way to suggest which edge was which.

Here are photomicrographs of some LaTene blades from a German monograph. I would love to tell you about them… but I can’t read German… sorry. The bottom is clearly a cross-section of the blade showing the piled structure. I think the image above it is a longitudinal section of the blade.

ks

LaTene Blade Cross Section

Hi Kirk,

You wrote:

I suppose you might have guessed that one of us would ask for some pics of the finished blade :) If you still have it, I would love to see the end result.

Cheers,

David

You wrote:

| Quote: |

| To reproduce this “piled” look in my LaTene blade, I had a local bladesmith forge me a blade blank out of cable Damascus. He used a large single cable to produce a look somewhat similar to this diagonal piled structure |

I suppose you might have guessed that one of us would ask for some pics of the finished blade :) If you still have it, I would love to see the end result.

Cheers,

David

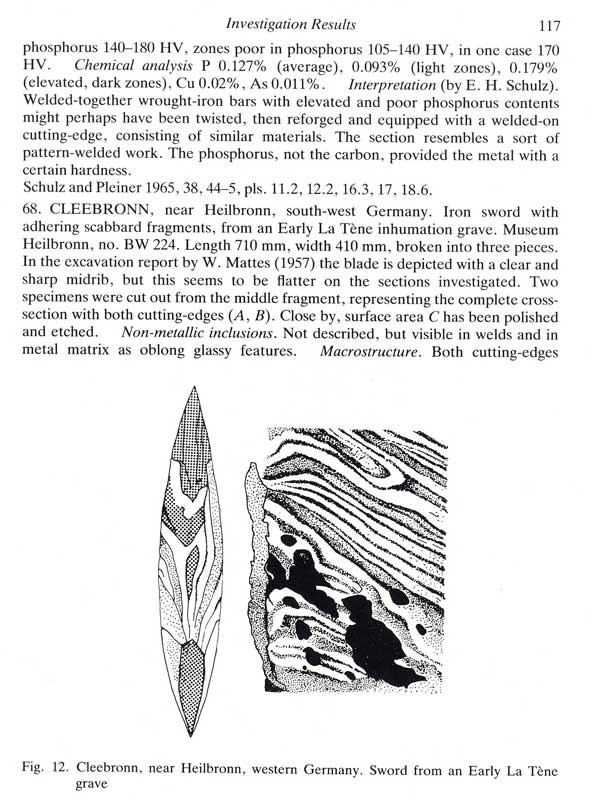

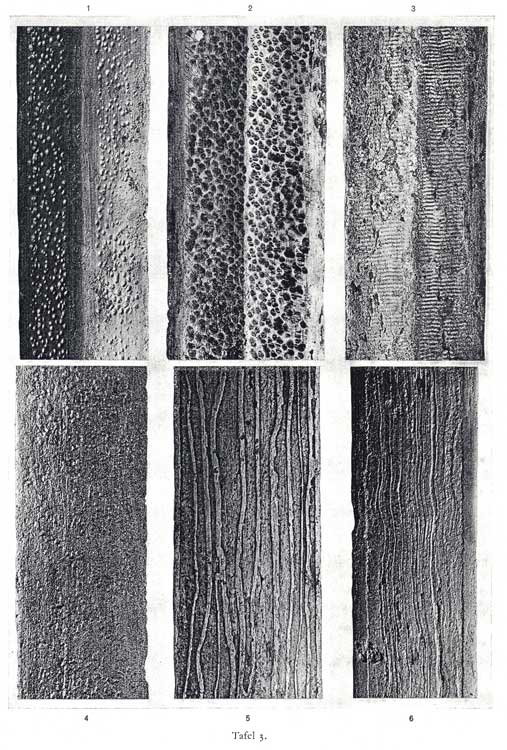

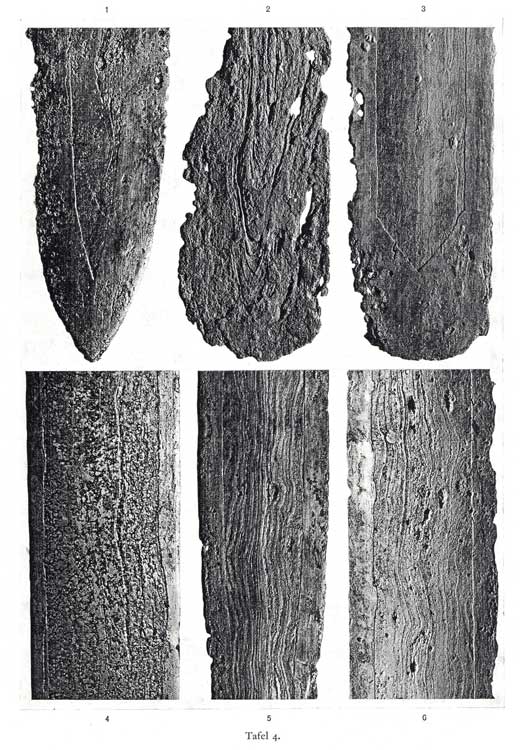

While we are on the subject, there is one more interesting feature to these blades. Many of these LaTene blades have patterns on the surface, which might appear to be evidence of this piled structure. Some times it is. But some times it can be produced by deliberate hammering with dies either for decoration or possibly as a form of work-hardening. Many other times it is just an artifact of the corrosion process in the scabbard or in the mud of the lake bottom.

Thanks for taking time to read these posts… remember I am working from memory here. If I spoke amiss please correct me.

ks

Attachment: 97.28 KB

Attachment: 97.28 KB

Top three blades are patterns hammered into the surface. Bottom three are corrosive patterns

Attachment: 91.22 KB

Attachment: 91.22 KB

Top three blades corrosive patterns of scabbard. Not sure about the bottom three?

Thanks for taking time to read these posts… remember I am working from memory here. If I spoke amiss please correct me.

ks

Top three blades are patterns hammered into the surface. Bottom three are corrosive patterns

Top three blades corrosive patterns of scabbard. Not sure about the bottom three?

| David McElrea wrote: | ||

| Hi Peter,

You wrote:

Was it common for the edges to be patternwelded? I had always assumed it was normally just the core-- but my assumptions were just that... assumptions (I plead ignorance). David |

Hi David,

You are correct, the edges may be of streaky steel but this material is as a rule not welded together to prodcue a pattern.

This is true for most european swords during the period when pattenrwelding was used as a regular production technique.

Hi Kirk,

Thank you for excellent posts!

An archaeolometallurgist once said to me that she suspected the La Téne blades with hammered surfaces might well be made (at least partially) from iron with a slight and well distributed phosphorous content. This material responds favourably to cold working.

This is just a theory and need to be tested to see its validity, but its interesting.

Hammering patterns could also have been done just to mimic patternwelding.

Fake patterns (of different design) were chiseled into spearheads of Scandinavian make during the roman iron age, found in the Danish bog finds.

Thank you for excellent posts!

An archaeolometallurgist once said to me that she suspected the La Téne blades with hammered surfaces might well be made (at least partially) from iron with a slight and well distributed phosphorous content. This material responds favourably to cold working.

This is just a theory and need to be tested to see its validity, but its interesting.

Hammering patterns could also have been done just to mimic patternwelding.

Fake patterns (of different design) were chiseled into spearheads of Scandinavian make during the roman iron age, found in the Danish bog finds.

Last edited by Peter Johnsson on Sun 25 Apr, 2004 11:30 pm; edited 1 time in total

| Quote: |

| The patternwelding is very evident on this one. Note that the edges are *not* patternwelded, only the core. |

I suspect the edges are patternwelded, but with a much finer grain than the core. In modern smithing terms, it would have a much higher layer count, indicating the steel in the edges was much more refined than the core. This can be seen in many older japanese blades, also. I admit that I am guessing, but the logic is there. It does not show any real pattern development, however. Facinating subject.

Thank you all for the very informative answers! The construction of blades with welded edges seems to be quite complex. However do you think that the smiths knew really how to purify their raw material or was it more of a trial and error base (although most of all learning goes this way). How deep has the knowledge of metallurgy really been?

Questions over questions....

Herbert

Questions over questions....

Herbert

| G Ezell wrote: | ||

I suspect the edges are patternwelded, but with a much finer grain than the core. In modern smithing terms, it would have a much higher layer count, indicating the steel in the edges was much more refined than the core. This can be seen in many older japanese blades, also. I admit that I am guessing, but the logic is there. It does not show any real pattern development, however. Facinating subject. |

By using the term patternwelding, I assume that some attempt att producing some form of decorative pattern was made. With this definition of the term, the edge steel was *not* patternwelded, but plied, layered, folded or whatever term you may choose. No attempt at producing a pattern was made.

The layering or streakiness of the edge steel is a result of a forging/welding process that was done to purify and homogenize the material. This was a necessary step in the making of steel of adequate quality.Today this is sometimes confused with patternwelding. It *is* a repeated folding and welding, but the result is a more or less irregular layering of straight layers without any aesthetic attempts. Any consious pattern effect is not seen in the edges of these weapons.

The best steel produced was pretty homogenous and did not show an obvious pattern. Today archaeological examples show a structure that is a result of corosion. At their time of use the layering of the steel the edges would have been very discreet or hardly visible at all.

| David McElrea wrote: | ||

| Hi Kirk,

You wrote:

I suppose you might have guessed that one of us would ask for some pics of the finished blade :) If you still have it, I would love to see the end result. Cheers, David |

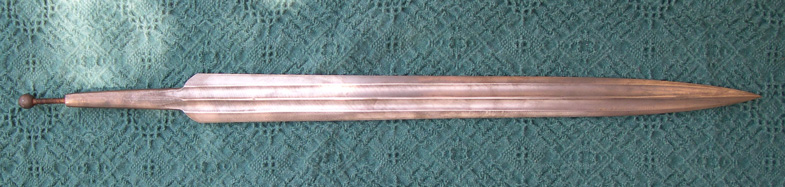

Hi David...

As with most of my projects, the aforementioned blade is in Spencerian pergatory... That half-finished waiting to be purified or condemed to hell Limbo in the back of my closet.

When I got the blade it was over 3.5 lbs. That means I've got to grind off at least a pound or so... probably more. Most of the mass will be removed widening, and deepening the fullers. A double fuller was forged into the blade. However, the early LaTene blades were more of a hollow grind with raised flats along the edge. To get this look I will need to widen the fullers, especially in the upper part of the blade near shoulders.

This is a difficult project because I can not seem to designing a hilt that is inspired by the rare historical evidence that exists and, at the same time, looks like it belongs with this type of blade. (The reconstructions I have seen of LaTene hilts look really goofy IMHO) However, Albions first attempt with their LaTene sword was very nice.

So far all I have done to this blade is polished it up and etched it to try to get an idea of the pattern and where the welds are. In the pics, you can see the cable pattern and it does resemble (somewhat) the earliest piled structures shown in the Cleeburn blade.

ks

Hi Kirk,

Thanks very much for the photos and commentary-- unfinished or not, that is a stunning blade! I trust it won't be condemned to Limbo for long, in any case.

In re: modern interpretations of hilts, I am in agreement with you-- many do look "wrong". Judging by one of Peter's comments in another thread, it seems like the complexity of the hiltwork presents some challenges for the one doing the interpreting.

I really hope to see a photo of the finished artlcle nonetheless. By the way, where is Cleeburn?

David

Edit: Sorry-- reading back over the other posts I've connected the dots-- you were referring to the "Cleebronn" blade from the texts you had scanned.

Also, how long is the blade itself, not including the tang?

Thanks very much for the photos and commentary-- unfinished or not, that is a stunning blade! I trust it won't be condemned to Limbo for long, in any case.

In re: modern interpretations of hilts, I am in agreement with you-- many do look "wrong". Judging by one of Peter's comments in another thread, it seems like the complexity of the hiltwork presents some challenges for the one doing the interpreting.

I really hope to see a photo of the finished artlcle nonetheless. By the way, where is Cleeburn?

David

Edit: Sorry-- reading back over the other posts I've connected the dots-- you were referring to the "Cleebronn" blade from the texts you had scanned.

Also, how long is the blade itself, not including the tang?

Hi David...

You're right. It is the piled structure of the "Cleebronn" blade that I was trying to duplicate.

The blade is 24 inches long... The finished sword will be around 29 to 30 inches.

What makes designing a hilt for the early LaTene so difficult---for me at least---is that the shape of the components are very "three dimensional." Like Celtic art itself, it is organic and the flowing lines must be integrated well. The delicate curves of the blade and fullers and bell-shaped guard should be reflected in the reconstructed wooden components. The pommel is especially difficult...

ks

You're right. It is the piled structure of the "Cleebronn" blade that I was trying to duplicate.

The blade is 24 inches long... The finished sword will be around 29 to 30 inches.

What makes designing a hilt for the early LaTene so difficult---for me at least---is that the shape of the components are very "three dimensional." Like Celtic art itself, it is organic and the flowing lines must be integrated well. The delicate curves of the blade and fullers and bell-shaped guard should be reflected in the reconstructed wooden components. The pommel is especially difficult...

ks

Page 1 of 2

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum