Yes I'll send you a more detailed description that was given to me privately, I owe you something else as well which I think I can get set up tonight. The thing on the spearhead is apparently not ready for publication yet so I don't want to spill any beans prematurely.

I think it's a combination of some of the specific qualities of certain metals as you described, and also something about the way different metals are put together. I've seen both in other contexts. The important role of impurities such as vanadium in wootz steel has been examined, and we know a lot about how Japanese swords were put together for example.

J

In The Sword and the Crucible, Alan Williams argues that - at least after 1400 in Europe - steel cores were strictly superior to iron cores as far as durability went because steel lower slag content. This counters the idea of iron as the optimal material for a sword's core.

As far as crossbow speed goes, note that some of the solid spring steel (MS416) crossbows listed here manage up to 71 m/s. That's likely approximately enough to send Payne-Gallwey's 85-gram bolt the recorded 400 or so meters. While the linked numbers aren't from medieval designs, the performance still suggest the possibility of achieving high velocity with steel bows. It's also interesting to observe that these nonmedieval steel crossbows drawing about 300lbs would make pretty decent weapons according to the linked numbers. It's uncanny how closely the performance of the Gamma v4 bow with the 29.39-gram bolt aligns with my calculations of Payne-Gallwey's famous shot. I'm admittedly using a very crude measure - kinetic energy output divided by power stroke times draw weight - but the consistency is impressive.

Gamma v4: 10-in power stroke x 300lb draw = 3000, 74 J/3000 = 0.02467

Payne-Gallwey: 7-in power stroke x 1,200 draw = 8400, 208 J/8400 = 0.02476

As far as crossbow speed goes, note that some of the solid spring steel (MS416) crossbows listed here manage up to 71 m/s. That's likely approximately enough to send Payne-Gallwey's 85-gram bolt the recorded 400 or so meters. While the linked numbers aren't from medieval designs, the performance still suggest the possibility of achieving high velocity with steel bows. It's also interesting to observe that these nonmedieval steel crossbows drawing about 300lbs would make pretty decent weapons according to the linked numbers. It's uncanny how closely the performance of the Gamma v4 bow with the 29.39-gram bolt aligns with my calculations of Payne-Gallwey's famous shot. I'm admittedly using a very crude measure - kinetic energy output divided by power stroke times draw weight - but the consistency is impressive.

Gamma v4: 10-in power stroke x 300lb draw = 3000, 74 J/3000 = 0.02467

Payne-Gallwey: 7-in power stroke x 1,200 draw = 8400, 208 J/8400 = 0.02476

I'm personally a lot more convinced by Alan Williams work on armor than on swords, which is a bit more complex of a subject.

J

J

Benjamin H Abbot wrote

Note though that the bows referred to are performance bows with a height to thickness ratio of about 2:1. Medieval bows generally have a ratio of 3.5:1 approx. This larger ratio makes for a much lazier bow and I guess they did this for safety reasons. It is possible to use the same material in different ratios, keep the same draw weight and have a very differently behaving bow. Our predecessors ran lazy bow sections rather than performance ones, so this document cannot really be used comparatively.

Tod

| Quote: |

| As far as crossbow speed goes, note that some of the solid spring steel (MS416) crossbows listed here manage up to 71 m/s. |

Note though that the bows referred to are performance bows with a height to thickness ratio of about 2:1. Medieval bows generally have a ratio of 3.5:1 approx. This larger ratio makes for a much lazier bow and I guess they did this for safety reasons. It is possible to use the same material in different ratios, keep the same draw weight and have a very differently behaving bow. Our predecessors ran lazy bow sections rather than performance ones, so this document cannot really be used comparatively.

Tod

It shows it is possible to achieve high speed with steel. They're certainly not medieval designs, but the basic material is similar. I'm inclined to believe Payne-Gallwey accurately reported his famous shot and that the crossbow used somehow made better use of the material for speed than many reproductions do. It's certainly possible he misrepresented or miscalculated, and that medieval steel crossbows couldn't shoot so far.

Looking at the numbers again, I'm not sure what you mean by this. I don't see a measure of height in the linked document, nor do any of the bow statistics combine to produce the ratio you list. The width to thickness ratio for Gamma v4 is nearly 5:1 (40/8.2). The the width to thickness ratio for the Payne-Gallwey bow is 2.5:1.

| Quote: |

| Note though that the bows referred to are performance bows with a height to thickness ratio of about 2:1. Medieval bows generally have a ratio of 3.5:1 approx. |

Looking at the numbers again, I'm not sure what you mean by this. I don't see a measure of height in the linked document, nor do any of the bow statistics combine to produce the ratio you list. The width to thickness ratio for Gamma v4 is nearly 5:1 (40/8.2). The the width to thickness ratio for the Payne-Gallwey bow is 2.5:1.

Well, maybe we are stuck on crossbows for the moment, but somebody seems to have moved the ball quite far on torsion spring weapons recently.

This is a pretty big deal potentially.

[ Linked Image ]

For non German speakers, you can copy and paste this into google translate

Quick summary, they did a test of 'scorpion' torsion spring crossbows (ok, not quite crossbows, shooting weapons?) which were allegedly used at the Battle of Teutoburg forest. First they did a computer simulation and then, apparently, they made replicas with the help of a bunch of engineers (which you can see in the image above).

The article says they had a range of 'several hundred meters', the energy was so high that they burnt the pig carcasses they were shooting? Wow. And a rate of shots at about 3-5 bolts per minute. According to records 60 of these were issued to each legion. From the image I posted above, (from the article) it does look like the targets are pretty far away.

I want to see video! As far as I know nobody had yet made a really effective torsion weapon of this type that really lived up to what it was supposed to be able to do - it sounds like they finally did in this case.

In "Gallic Wars" Caesar mentions these weapons as being extremely important, they saved him in Britain for example.

http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/technik/to...41289.html

G

This is a pretty big deal potentially.

[ Linked Image ]

For non German speakers, you can copy and paste this into google translate

Quick summary, they did a test of 'scorpion' torsion spring crossbows (ok, not quite crossbows, shooting weapons?) which were allegedly used at the Battle of Teutoburg forest. First they did a computer simulation and then, apparently, they made replicas with the help of a bunch of engineers (which you can see in the image above).

The article says they had a range of 'several hundred meters', the energy was so high that they burnt the pig carcasses they were shooting? Wow. And a rate of shots at about 3-5 bolts per minute. According to records 60 of these were issued to each legion. From the image I posted above, (from the article) it does look like the targets are pretty far away.

I want to see video! As far as I know nobody had yet made a really effective torsion weapon of this type that really lived up to what it was supposed to be able to do - it sounds like they finally did in this case.

In "Gallic Wars" Caesar mentions these weapons as being extremely important, they saved him in Britain for example.

http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/technik/to...41289.html

G

I've been thinking more about the 1200lb bow tested by Payne-Gallwey. Looking at the numbers from The Great Warbow assuming similar ballistic properties for the crossbow's bolts, it may have needed an initial speed of 75 m/s - or higher - to reach 450 yards. 75 m/s would be 245 J given the 3oz bolt. Assuming this is right, the same bow could probably deliver 300 J with a 5oz bolt.

Scaling down to the 1000lb crossbows Payne-Gallwey and others say saw infantry use in field - what are the sources for this, by the way? - you might get 200 J with a lighter bolt and 240 J with a heavier one. With the same efficiencies and assuming a linear force curve, the strongest of the goat's-foot-lever-spanned South Padre Island Spanish crossbows would deliver 85-115 J up close depending on bolt weight.

Scaling down to the 1000lb crossbows Payne-Gallwey and others say saw infantry use in field - what are the sources for this, by the way? - you might get 200 J with a lighter bolt and 240 J with a heavier one. With the same efficiencies and assuming a linear force curve, the strongest of the goat's-foot-lever-spanned South Padre Island Spanish crossbows would deliver 85-115 J up close depending on bolt weight.

This may be one of those elusive 'whistling' bolt heads

http://picasaweb.google.com/lh/photo/zurfz-7OvNyvJujj4KIOZg

J

http://picasaweb.google.com/lh/photo/zurfz-7OvNyvJujj4KIOZg

J

| Jean Henri Chandler wrote: |

| Well, maybe we are stuck on crossbows for the moment, but somebody seems to have moved the ball quite far on torsion spring weapons recently.

The article says they had a range of 'several hundred meters', the energy was so high that they burnt the pig carcasses they were shooting? Wow. And a rate of shots at about 3-5 bolts per minute. According to records 60 of these were issued to each legion. From the image I posted above, (from the article) it does look like the targets are pretty far away. |

This is not so new as the authors say. Effective reconstructions like this are around for 20 years now. So far we achieved a max range of ca. 220m.

Also, I think 3 - 5 bolts per minute is a low estimate. With some hours of scorpio drill over 2 days and a few adjustments on the weapon we (legio8augusta.de) managed a record of 12 bolts fired in 60 secs with a 3 man crew :-)

You can see the scorpio we used for that in when we had the chance to test it back in 2011 (I think it was) at the Fraunhofer Institute for High-Speed Dynamics (http://www.en.emi.fraunhofer.de/) here: www.planet-schule.de/sf/php/02_sen01.php?sendung=8624 (jump to minute 11:00, in German)

Interesting, thanks. What do you think the effective range is for aimed shots as opposed to sort of 'area' shots?

J

J

I'd say under 100m. I personally think this weapon was at its best when employed in larger numbers firing at a bigger body of opponents at ranges where the targets had a few minutes to cover in order to close with the enemy. During that time they would have suffered a steady rain of bolts without a chance to retaliate. The bolts hurt not only bodies but also morale. Not that I have any proof that this was the thinking back then, though.

Probably not too far from the mark. If the engines could concentrate on a small segment (or several small segments) of the enemy's line rather than spreading their shots evenly across the line, they'd create weak points that could be exploited with a countercharge -- or a plain charge if the Romans were the attacking side. Alternatively, a barrage of missiles like that could be used to incite the enemy to attack and leave a prepared or advantageous position they originally wanted to defend.

Hi all !

I'm bringing this thread back to life, they are some really nice stuffs that have been posted and I think it should continue, because more can be done about the whole thing.

Being quite experienced as an archer, and liking to go into the technical aspect of things, I wanted to gather information about medieval crossbows and process it the way things are done in modern archery technical reviews. Some people here started talking about kinetic energy, this is a good way to go if we want to have a good comparison point between crossbows themselves or in regard to the English warbow. (Sorry if that sounds a bit like the "know everything" guy, I'm not and it was not intended :D )

I will not try to guesstimate anything related to penetration performances. There is too much parameters as bolt speed, weight, balance point, point size and shape, target shape material and support, angle of strike, etc... This is just not realistic to try to asses any weapon performance on backyard home tests.

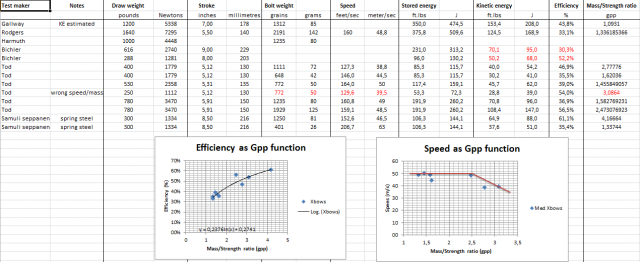

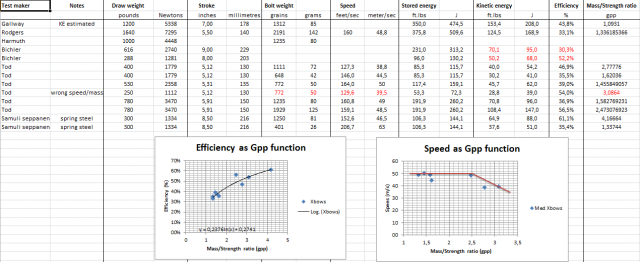

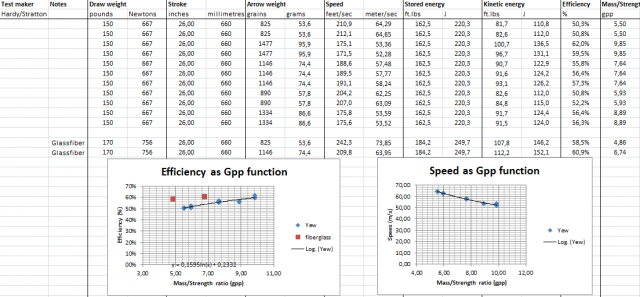

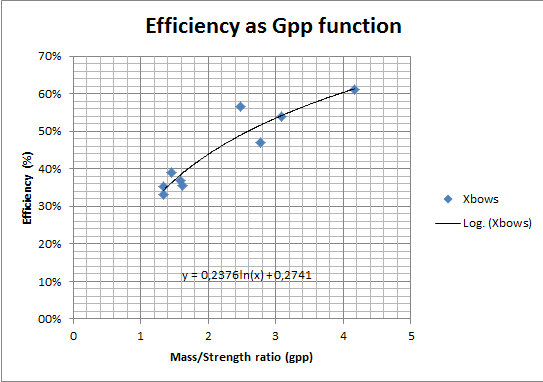

Now, I've put the data I found in this thread into an excel sheet and tried to come up with the kind of information that are usually used to compare trad bows. This is a simplified version assuming a linear relationship between stroke and draw weight, which is close to reality for an English longbow/warbow. I assume it shouldn't be much different with a bow from a medieval crossbow.

I have done this for crossbows using available data here in order to try to see the global trend of the performance of a "medieval" crossbow in relationship with it's draw weight, stroke and bolt weight.

I also entered the data from Robert Hardy's book The Great Warbow, given how it was performed this is just solid data about how a warbow would perform.

How it looks like :

For crossbows

For warbows

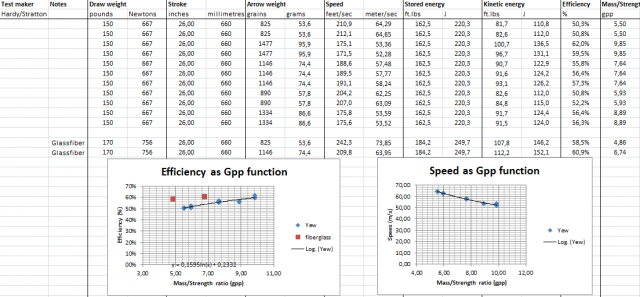

I will start with the warbow spreadsheet :

- All the shots with full information are entered here, except the first one (it's speed reading is way over the overall trend, and as we have no speed reading for shot n°2, I'm skeptical about that particular value). For each shot the Kinetic energy of the arrow as it leaves the bow is calculated (it is readily available in the book but this allows to compare for eliminating a possible stupid mistake !). The stored energy is also calculated, as the bow is said to be drawn at 32 inches, minus 6 inches of brace height. I also included the two shots from the 170# fiberglass bow he used, assuming also 32"DL and 6"BH

-From this point two results are calculated : first the efficiency of the bow for that particular arrow (arrow KE/stored E) and the second is the weight of the arrow in relationship with the bow strength, unit is the grain per pound (gpp) wich is in current use in the archery world.

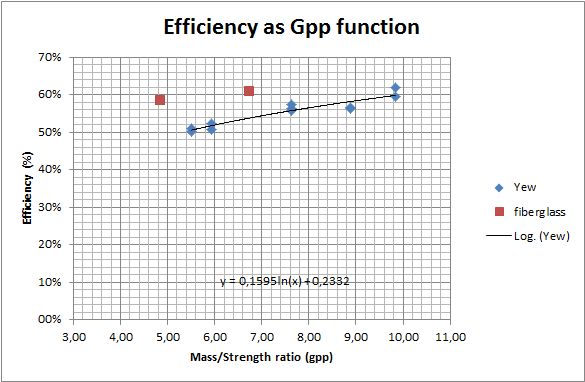

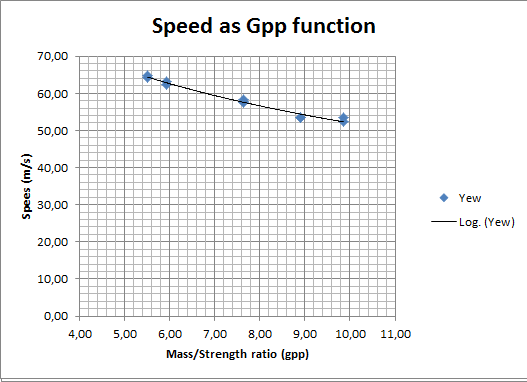

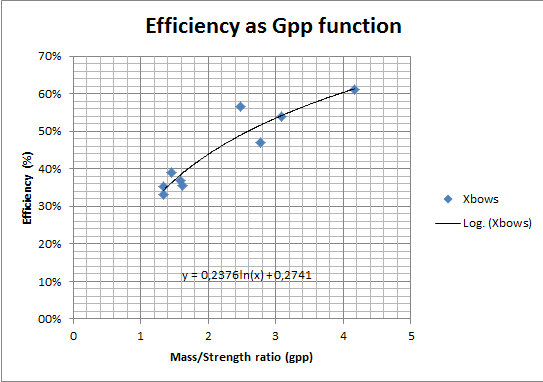

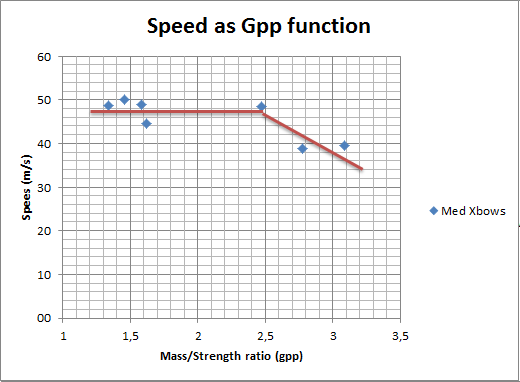

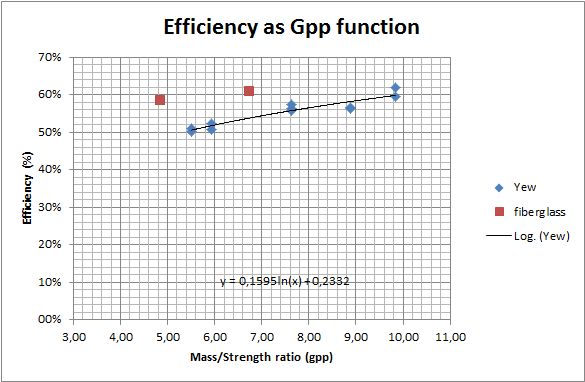

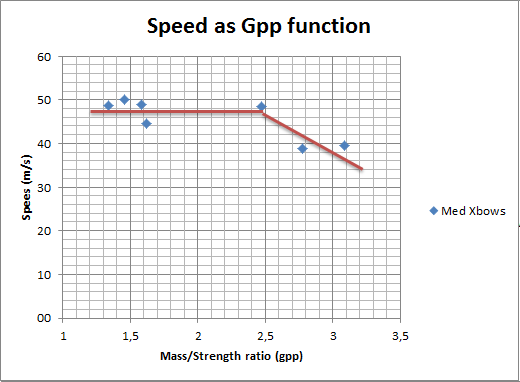

-Then I draw two charts, one giving the efficiency of the bow for a particular gpp value, and the second chart is the speed of that projectile also as function of the gpp value.

Here are a closeup views of these charts :

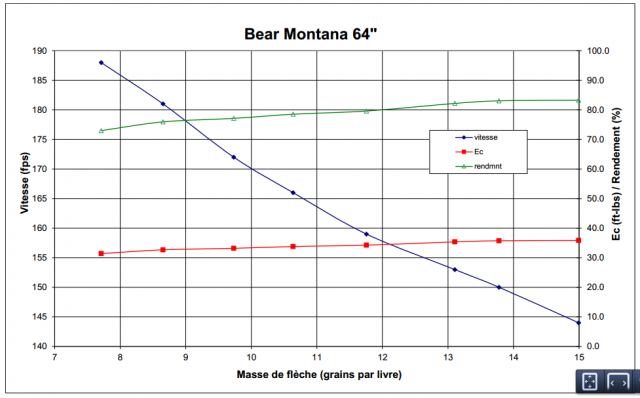

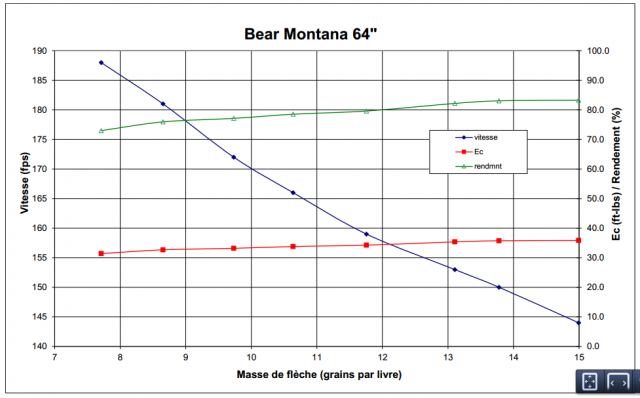

And for the sake of comparison, here is the graph of one of my own flatbows, a bear montana (64" long, 50# @28" and 7" brace height)

The format is a bit different but you still have the gpp value on X axis, speed value on left vertical axis (blue, fps) and both kinetic energy (red, ft.lbs) and efficiency (green, %) on the right vertical axis.

What can be told from the Warbow charts :

First, the efficiency is quite low, ranging from 50 to 60%, this is not as surprising regarding about the gpp value, as 5gpp is really low. Most of modern traditional bows will not accept anything under 8gpp. 10gpp is considered to be a good value, and 12gpp brings you a bit more penetration for hunting purposes, if your draw weight is a bit on the weak side. Around 10gpp, the warbow is around 60% efficiency. Old style fiberglass bows (howard hill) turns around 65% of efficiency at that value, depending on their length. Modern deflex/reflex bows usually climbs up to 75-80% at 10gpp

My own replicas of medieval war arrows (33" ash shafts, 1/2" diameter at the point tapering to 3/8" at the nock, horn nock reinforcement and three 7"3/4 feathers with a 200gr tudor bodkin (machined, not forged though) are weighting 80g on average. out of Stratton's bow it would be 8.21gpp, so an efficiency around 57%

The two red dots are the 170# fiberglass bow shot by Stratton, with a higher efficiency the the warbow even at low weight arrows. It would probably reach the classic 65% efficiency if the curve was extended to 10gpp.

From the second chart, yew warbows can hit a speed of 65m/s with "light" arrows but would probably settle between 50 and 55m/s with heavier war arrows.

Going a bit further, if we look at archaeological evidences, at it has already been pointed out that the Mary Rose arrows were only 30" long, and thus archers at that time would only draw their bows to 29 to 30 inches. Knowing the efficiency of the bow (60% with heavier arrows) :

150lbs drawn at 32" gives around 136J of kinetic energy (measured in the book)

150lbs at 30" would give 121.8J of kinetic energy, and 116.4 at 29" (10,5% and 14.5% decrease respectively)

Now on to the crossbows

About the spreadsheet : the data posted on the thread are here for the most part.

The shot taken by Sir Payne Gallwey lacks the values for speed and Kinetic energy. I entered the estimated 208J value from Benjamin.

For Harmuth test, I don't see any mention of the stroke of the bow used. Same for Bichler tests, no mention of the bolt weight used. If you have that info somewhere, I would gladly put them in the table. There is a mention of 67m/s for Harmuth crossbow on another forum but this is completely unrealistic given how all others crossbows perform.

Thanks a lot to Tod, his own tests are making the solid part of these data. There is a little something wrong in the number posted : both the 530# and the 250# crossbows shot the same 50g bolt at 50m/s. As the KE is different, I guess that the correct speed value for the 250# would be 39.5m/s

Of course all crossbows doesn't behave exactly the same, but what I try to achieve here is to get a rough curve of how medieval steel crossbows tend to perform.

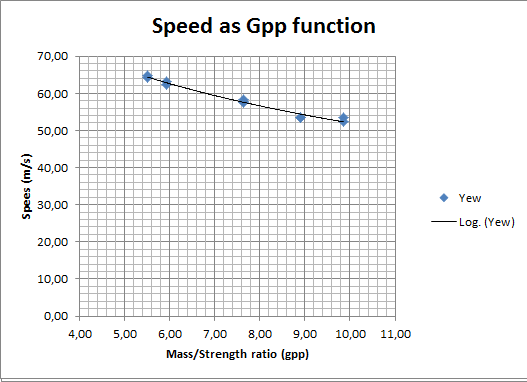

Using the same processing as for the warbow, here are the charts :

What can be told from these charts :

First, we can see that with the bolt used, the gpp value is way inferior to that of the warbows. The efficiency with light projectiles is also under the average warbow value, but not far off with heavier ones. There is a big bulk in the 33% to 39% with gpp values around 1.3-1.4. It must be noted that the extreme ends of these tests tells us the same : from the 1640# crossbow from Rodgers as well as the 300# crossbow from Samuli Seppanen, with Tod's 780#, 530# and 400# crossbows in between.

With heavier bolts, the efficiency seems to climb rather quickly to something around 50% at 3gpp and reaching the warbow's efficiency of 60% at 4gpp. I would like to have more data on these parts of the curve to be able to see a much clearer trend, or at least, make sure that these approximations are reliable.

On the second chart, we can see that crossbows indeed differ from selfbows in regard to maximum speed. The curve seems to stack somewhere under the 50m/s, no matter how light the bolt is. (This is why I discarded the second hand 67m/s value supposedly from Harmuth, plus the efficiency value gives 58% at 1.2gpp).

As I have no real info of how Samuli Seppanen built his crossbow, I did not put his values either, as the 63m/s is way over the trend (for now). Depending on how it is built, it could possibly reach higher values. For comparison a modern crossbow (excalibur matrix 355) with 240# recurve bow (not a compound design) and 12.2" stroke sends a 350gr bolt at 355fps (108.2m/s), this is 78% efficiency at 1.46gpp ! So there is a lot of room for improvement.

I draw the two red lines according to Tod experiments, as he said that speed noticeably decreases past a certain weight, which in his cases corresponds to 2.45gpp. The two values above that point are also from Tod, with 2.47 and 2.77 gpp.

For Samuli Seppanen values in the first curve, I'm not sure if I have to leave them or not. The speed readings are somewhat off but the efficiency at low gpp is spot on with the others and the value at 4.16gpp (also being the only one available) seems that it could fit with the others.

For now it could be said that using around 2.4gpp bolt weight would achieve the best compromise between speed and efficiency.

Personal thoughts

Even if this model is not complete, and I don't pretend that it is accurate either, but it gives a rough idea of what could be expected in terms kinetic energy and speed (the latter being the least solid value) from a medieval crossbow with a given set of draw weight, stroke and bolt weight.

On to the criticized shot from Sir Payne Gallwey :

@ Ben : with the 208J you estimated earlier, it would give something like 44% efficiency for 1.1gpp. If you crank it down to something like 180J, it will give something like 38% efficiency, which is still high but more in the trend with the others.

Personally, I don't think that using the same drag specs as english war arrow is accurate for these long shots. You have a projectile that is more than twice as short and with two fins instead of three feathers. Given how important size and shape of feathers is to archers practicing flight shooting or shooting at 100yds nowadays (with English longbows), as they trim it sometimes to something parabolic as small as 2" long and 1/2" height, the big three triangular 8" by 1" feathers with their floppy uncut tails do generate a great amount of drag. It stabilizes the arrow way better though. I think that a bolt with it's two rigid wooden fins is much more efficient as far as aerodynamic is concerned.

If you use a lower value for drag in your calculations (let's say half of that of a war arrow, no idea of the real drag of a medieval bolt) what would be the output for the KE needed ? (I don't know much about ballistics formulas :D )

Also things like a tail wind during the shot may have helped, even if he doesn't mention it in the book. If you include this also in the formula, using for example the same 9m/s tail wind that Stratton had during his testings for the warbow, will this push the bolt significantly further ?

Concerning the maximum achievable speed of bolts, your other post about the 206fps needed to carry the bolt to the 460yds puzzles me a bit. There is something Sir Gallwey mention : the fact that some bow limbs are bent upwards.

From Sir Gallwey book :

From the link given for Samuli Seppanen crossbow, it speaks of the same cant on the limbs. And surprisingly, his shot with his 300# 8.5"stroke crossbow and 26g bolt (1.34gpp) hits that 206fps mark. Could this design of the bow really improve how fast the bolt can be propelled ?

@Tod : Do your bows features this upward cant on the limbs (rather than on the bow itself) or have you already tried it on some prototypes before ?

Additionally, both these bows features a longer stroke than every other documented here (complete data about Bichler shots would be very welcome here), maybe the short stroke limits for some obscure reason the maximum speed of the bolt.

I hope you all carried out to the end without sleeping, and that the explanations given are clear enough (I'm not native english so apologies for the mistakes in the text). Any critics are welcome, and feel free to add any new serious data you can find in books or by testing it yourself. Also it could be great to have additional data about how wooden/composite crossbows behave to compare with steel ones.

I'm bringing this thread back to life, they are some really nice stuffs that have been posted and I think it should continue, because more can be done about the whole thing.

Being quite experienced as an archer, and liking to go into the technical aspect of things, I wanted to gather information about medieval crossbows and process it the way things are done in modern archery technical reviews. Some people here started talking about kinetic energy, this is a good way to go if we want to have a good comparison point between crossbows themselves or in regard to the English warbow. (Sorry if that sounds a bit like the "know everything" guy, I'm not and it was not intended :D )

I will not try to guesstimate anything related to penetration performances. There is too much parameters as bolt speed, weight, balance point, point size and shape, target shape material and support, angle of strike, etc... This is just not realistic to try to asses any weapon performance on backyard home tests.

Now, I've put the data I found in this thread into an excel sheet and tried to come up with the kind of information that are usually used to compare trad bows. This is a simplified version assuming a linear relationship between stroke and draw weight, which is close to reality for an English longbow/warbow. I assume it shouldn't be much different with a bow from a medieval crossbow.

I have done this for crossbows using available data here in order to try to see the global trend of the performance of a "medieval" crossbow in relationship with it's draw weight, stroke and bolt weight.

I also entered the data from Robert Hardy's book The Great Warbow, given how it was performed this is just solid data about how a warbow would perform.

How it looks like :

For crossbows

For warbows

I will start with the warbow spreadsheet :

- All the shots with full information are entered here, except the first one (it's speed reading is way over the overall trend, and as we have no speed reading for shot n°2, I'm skeptical about that particular value). For each shot the Kinetic energy of the arrow as it leaves the bow is calculated (it is readily available in the book but this allows to compare for eliminating a possible stupid mistake !). The stored energy is also calculated, as the bow is said to be drawn at 32 inches, minus 6 inches of brace height. I also included the two shots from the 170# fiberglass bow he used, assuming also 32"DL and 6"BH

-From this point two results are calculated : first the efficiency of the bow for that particular arrow (arrow KE/stored E) and the second is the weight of the arrow in relationship with the bow strength, unit is the grain per pound (gpp) wich is in current use in the archery world.

-Then I draw two charts, one giving the efficiency of the bow for a particular gpp value, and the second chart is the speed of that projectile also as function of the gpp value.

Here are a closeup views of these charts :

And for the sake of comparison, here is the graph of one of my own flatbows, a bear montana (64" long, 50# @28" and 7" brace height)

The format is a bit different but you still have the gpp value on X axis, speed value on left vertical axis (blue, fps) and both kinetic energy (red, ft.lbs) and efficiency (green, %) on the right vertical axis.

What can be told from the Warbow charts :

First, the efficiency is quite low, ranging from 50 to 60%, this is not as surprising regarding about the gpp value, as 5gpp is really low. Most of modern traditional bows will not accept anything under 8gpp. 10gpp is considered to be a good value, and 12gpp brings you a bit more penetration for hunting purposes, if your draw weight is a bit on the weak side. Around 10gpp, the warbow is around 60% efficiency. Old style fiberglass bows (howard hill) turns around 65% of efficiency at that value, depending on their length. Modern deflex/reflex bows usually climbs up to 75-80% at 10gpp

My own replicas of medieval war arrows (33" ash shafts, 1/2" diameter at the point tapering to 3/8" at the nock, horn nock reinforcement and three 7"3/4 feathers with a 200gr tudor bodkin (machined, not forged though) are weighting 80g on average. out of Stratton's bow it would be 8.21gpp, so an efficiency around 57%

The two red dots are the 170# fiberglass bow shot by Stratton, with a higher efficiency the the warbow even at low weight arrows. It would probably reach the classic 65% efficiency if the curve was extended to 10gpp.

From the second chart, yew warbows can hit a speed of 65m/s with "light" arrows but would probably settle between 50 and 55m/s with heavier war arrows.

Going a bit further, if we look at archaeological evidences, at it has already been pointed out that the Mary Rose arrows were only 30" long, and thus archers at that time would only draw their bows to 29 to 30 inches. Knowing the efficiency of the bow (60% with heavier arrows) :

150lbs drawn at 32" gives around 136J of kinetic energy (measured in the book)

150lbs at 30" would give 121.8J of kinetic energy, and 116.4 at 29" (10,5% and 14.5% decrease respectively)

Now on to the crossbows

About the spreadsheet : the data posted on the thread are here for the most part.

The shot taken by Sir Payne Gallwey lacks the values for speed and Kinetic energy. I entered the estimated 208J value from Benjamin.

For Harmuth test, I don't see any mention of the stroke of the bow used. Same for Bichler tests, no mention of the bolt weight used. If you have that info somewhere, I would gladly put them in the table. There is a mention of 67m/s for Harmuth crossbow on another forum but this is completely unrealistic given how all others crossbows perform.

Thanks a lot to Tod, his own tests are making the solid part of these data. There is a little something wrong in the number posted : both the 530# and the 250# crossbows shot the same 50g bolt at 50m/s. As the KE is different, I guess that the correct speed value for the 250# would be 39.5m/s

Of course all crossbows doesn't behave exactly the same, but what I try to achieve here is to get a rough curve of how medieval steel crossbows tend to perform.

Using the same processing as for the warbow, here are the charts :

What can be told from these charts :

First, we can see that with the bolt used, the gpp value is way inferior to that of the warbows. The efficiency with light projectiles is also under the average warbow value, but not far off with heavier ones. There is a big bulk in the 33% to 39% with gpp values around 1.3-1.4. It must be noted that the extreme ends of these tests tells us the same : from the 1640# crossbow from Rodgers as well as the 300# crossbow from Samuli Seppanen, with Tod's 780#, 530# and 400# crossbows in between.

With heavier bolts, the efficiency seems to climb rather quickly to something around 50% at 3gpp and reaching the warbow's efficiency of 60% at 4gpp. I would like to have more data on these parts of the curve to be able to see a much clearer trend, or at least, make sure that these approximations are reliable.

On the second chart, we can see that crossbows indeed differ from selfbows in regard to maximum speed. The curve seems to stack somewhere under the 50m/s, no matter how light the bolt is. (This is why I discarded the second hand 67m/s value supposedly from Harmuth, plus the efficiency value gives 58% at 1.2gpp).

As I have no real info of how Samuli Seppanen built his crossbow, I did not put his values either, as the 63m/s is way over the trend (for now). Depending on how it is built, it could possibly reach higher values. For comparison a modern crossbow (excalibur matrix 355) with 240# recurve bow (not a compound design) and 12.2" stroke sends a 350gr bolt at 355fps (108.2m/s), this is 78% efficiency at 1.46gpp ! So there is a lot of room for improvement.

I draw the two red lines according to Tod experiments, as he said that speed noticeably decreases past a certain weight, which in his cases corresponds to 2.45gpp. The two values above that point are also from Tod, with 2.47 and 2.77 gpp.

For Samuli Seppanen values in the first curve, I'm not sure if I have to leave them or not. The speed readings are somewhat off but the efficiency at low gpp is spot on with the others and the value at 4.16gpp (also being the only one available) seems that it could fit with the others.

For now it could be said that using around 2.4gpp bolt weight would achieve the best compromise between speed and efficiency.

Personal thoughts

Even if this model is not complete, and I don't pretend that it is accurate either, but it gives a rough idea of what could be expected in terms kinetic energy and speed (the latter being the least solid value) from a medieval crossbow with a given set of draw weight, stroke and bolt weight.

On to the criticized shot from Sir Payne Gallwey :

| Quote: |

| As far as English warbow to crossbow comparisons go, the 1200lb crossbow Ralph Payne-Gallwey used to a shoot a three-ounce bolt 460 yards would have delivered around 200 J at close range. (Sending a three-ounce bolt that distance would require 171 J in a vacuum. Air resistance brings that up to 190-210 J based on the ratios I've seen for heavy English warbow arrows) |

@ Ben : with the 208J you estimated earlier, it would give something like 44% efficiency for 1.1gpp. If you crank it down to something like 180J, it will give something like 38% efficiency, which is still high but more in the trend with the others.

Personally, I don't think that using the same drag specs as english war arrow is accurate for these long shots. You have a projectile that is more than twice as short and with two fins instead of three feathers. Given how important size and shape of feathers is to archers practicing flight shooting or shooting at 100yds nowadays (with English longbows), as they trim it sometimes to something parabolic as small as 2" long and 1/2" height, the big three triangular 8" by 1" feathers with their floppy uncut tails do generate a great amount of drag. It stabilizes the arrow way better though. I think that a bolt with it's two rigid wooden fins is much more efficient as far as aerodynamic is concerned.

If you use a lower value for drag in your calculations (let's say half of that of a war arrow, no idea of the real drag of a medieval bolt) what would be the output for the KE needed ? (I don't know much about ballistics formulas :D )

Also things like a tail wind during the shot may have helped, even if he doesn't mention it in the book. If you include this also in the formula, using for example the same 9m/s tail wind that Stratton had during his testings for the warbow, will this push the bolt significantly further ?

Concerning the maximum achievable speed of bolts, your other post about the 206fps needed to carry the bolt to the 460yds puzzles me a bit. There is something Sir Gallwey mention : the fact that some bow limbs are bent upwards.

From Sir Gallwey book :

| Quote: |

| B, Fig. 58, next page, shows how the arms of the bow are slightly canted

up from its center. If a thread is held from the center of one end of the bow to the center of its other end, as per dotted line, it should be \ in. higher at its center than the upper edge of the bow, as the latter lies on its side on a table, x x, B, fig. 5 8 If the bow had not this upward cant, its bow-string would press so hard on the top of the stock that it would be unable to propel the bolt with proper force. The friction of the bow-string against the stock would prevent the string from acting freely when the bow recoiled from a bent position All the best steel bows were made in this manner, especially those used in the chase. On the other hand, many of the military crossbows had straight bows, which were merely canted upwards in their stocks to enable their bow-strings to work freely. |

From the link given for Samuli Seppanen crossbow, it speaks of the same cant on the limbs. And surprisingly, his shot with his 300# 8.5"stroke crossbow and 26g bolt (1.34gpp) hits that 206fps mark. Could this design of the bow really improve how fast the bolt can be propelled ?

@Tod : Do your bows features this upward cant on the limbs (rather than on the bow itself) or have you already tried it on some prototypes before ?

Additionally, both these bows features a longer stroke than every other documented here (complete data about Bichler shots would be very welcome here), maybe the short stroke limits for some obscure reason the maximum speed of the bolt.

I hope you all carried out to the end without sleeping, and that the explanations given are clear enough (I'm not native english so apologies for the mistakes in the text). Any critics are welcome, and feel free to add any new serious data you can find in books or by testing it yourself. Also it could be great to have additional data about how wooden/composite crossbows behave to compare with steel ones.

We'd really need to know the aerodynamics of the crossbow bolt in question precisely calculate the Payne-Gallwey shot. However, if it performed like the arrows in The Great Warbow test, it must have had something around 75 m/s - or more - to reach 410-420m. The Great Warbow 73.85-m/s shot with the flatbow only managed 387.7m. So if Payne-Gallwey's numbers are correct and the bolt wasn't any more aerodynamic than a warbow arrow, it liked had around 245+ J initially. So 208 J is likely a low estimate unless bolts are dramatically better at distance shooting than arrows. Wind at time of shooting is also a factor; I don't know if Payne-Gallwey mentioned that.

Thanks for reviving the thread Arnaud! Very interesting post.

It's nice to see the piecing together of datapoints. I'd like to see this continue, we need some more data points for the thread. I agree with you that bolt weight is a big one. I've seen some bolts recently and I know people who actually own some antique ones, I'll try to get some measurements there.

I think we are still missing some important information in figuring all this out. The modern tests with the composite prod bows (which continued to be used in many area alongside or even in preference too the steel prod) failed because they couldn't make them properly - the bows lost efficiency dramatically with each shot and were nearly useless by the end of the test. So clearly they have a lot to learn about making those kinds of crossbow prods.

Though we have been much more successful with the steel prods, this may possibly mask a similar gap in comparison to the ancient world. Some of the incredibly subtle nuances we have learned from people like Peter Johnsson about medieval swords tells me that there may be some aspects to making the steel prods in the manner they were done before the 18th Century may be more difficult in terms of metallurgy, tempering etc. than we are assuming.

I'd really like to see more data about the antiques, there is a forum I've found which might be a good place to ask some questions:

http://thearbalistguild.forumotion.com/

The 'string' may be another important factor. I know Tod has some safety concerns which how he does the strings. Part of the problem is that making a weapon for testing which might potentially be destructive is a luxury probably none of us can afford!

Jean

It's nice to see the piecing together of datapoints. I'd like to see this continue, we need some more data points for the thread. I agree with you that bolt weight is a big one. I've seen some bolts recently and I know people who actually own some antique ones, I'll try to get some measurements there.

I think we are still missing some important information in figuring all this out. The modern tests with the composite prod bows (which continued to be used in many area alongside or even in preference too the steel prod) failed because they couldn't make them properly - the bows lost efficiency dramatically with each shot and were nearly useless by the end of the test. So clearly they have a lot to learn about making those kinds of crossbow prods.

Though we have been much more successful with the steel prods, this may possibly mask a similar gap in comparison to the ancient world. Some of the incredibly subtle nuances we have learned from people like Peter Johnsson about medieval swords tells me that there may be some aspects to making the steel prods in the manner they were done before the 18th Century may be more difficult in terms of metallurgy, tempering etc. than we are assuming.

I'd really like to see more data about the antiques, there is a forum I've found which might be a good place to ask some questions:

http://thearbalistguild.forumotion.com/

The 'string' may be another important factor. I know Tod has some safety concerns which how he does the strings. Part of the problem is that making a weapon for testing which might potentially be destructive is a luxury probably none of us can afford!

Jean

The reason I say that we may still be missing something here is because while the Payne Gallway test may seem to be an outlier compared to our tests with replicas, his was the only one we know of (at least in this thread so far) done on an antique, and it's also much more in line with what I keep reading in period sources.

I've been doing a lot of research in the last few years into the context of the medieval fencing manuals and as a result, I've been reading a ton of period documents from the 15th Century. These range from the Chronicles of Hamburg and Strasbourg, to the Annales of Jan Dlugosz, to letters and books of Piccolomini and the records of the Teutonic Order, chronicles of two expeditions (with longbowmen) by Henry of Bolingbroke (Henry IV of England (before he was king)) into the Crusades in Luthuania, and letters from Matthias Corvinus. In all of these sources, the crossbow, across the board, is treated with a certain palpable sense of awe and fear as a weapon, and the few data points that I can find* seem to indicate it was at least on par with the firearms of the time, and seems to be more effective than the replicas. More like Gallways test. So maybe we still have more to learn.

To cite just two prominent examples, the Dauphin of France being wounded in the knee through his armor, apparently at some significant distance from the shooter, during the siege of a small town in 1444, (from the Strasbourg chronicle), and Sultan Mehmet being wounded by a crossbow at the siege of Belgrade in 1456. The way the Teutonic Order and the Genoese both refer to it's use against the Tartars also suggest that they believed it could be used to fend off horse-archers.

J

I've been doing a lot of research in the last few years into the context of the medieval fencing manuals and as a result, I've been reading a ton of period documents from the 15th Century. These range from the Chronicles of Hamburg and Strasbourg, to the Annales of Jan Dlugosz, to letters and books of Piccolomini and the records of the Teutonic Order, chronicles of two expeditions (with longbowmen) by Henry of Bolingbroke (Henry IV of England (before he was king)) into the Crusades in Luthuania, and letters from Matthias Corvinus. In all of these sources, the crossbow, across the board, is treated with a certain palpable sense of awe and fear as a weapon, and the few data points that I can find* seem to indicate it was at least on par with the firearms of the time, and seems to be more effective than the replicas. More like Gallways test. So maybe we still have more to learn.

To cite just two prominent examples, the Dauphin of France being wounded in the knee through his armor, apparently at some significant distance from the shooter, during the siege of a small town in 1444, (from the Strasbourg chronicle), and Sultan Mehmet being wounded by a crossbow at the siege of Belgrade in 1456. The way the Teutonic Order and the Genoese both refer to it's use against the Tartars also suggest that they believed it could be used to fend off horse-archers.

J

| Benjamin H. Abbott wrote: |

| We'd really need to know the aerodynamics of the crossbow bolt in question precisely calculate the Payne-Gallwey shot. However, if it performed like the arrows in The Great Warbow test, it must have had something around 75 m/s - or more - to reach 410-420m. The Great Warbow 73.85-m/s shot with the flatbow only managed 387.7m. So if Payne-Gallwey's numbers are correct and the bolt wasn't any more aerodynamic than a warbow arrow, it liked had around 245+ J initially. So 208 J is likely a low estimate unless bolts are dramatically better at distance shooting than arrows. Wind at time of shooting is also a factor; I don't know if Payne-Gallwey mentioned that. |

Dunno about aerodynamics, but balance, and more importantly, stiffness, most probably plays large role.

It's not uncommon to read about slower bow sending given arrow further than faster one, because from one reason or another release was more stable, and arrow lost less energy bending/shaking.

Similar thing may be the case with many heavier bolts.

It's just hard to speculate about theoretical trajectories based on velocity, while in fact every projectile has it own quirks, especially when released from different weapons.

This has been a fascinating if somewhat frustrating discussion. I have enjoyed reading through it but I doubt I am knowledgeable enough to really contribute. It seems what everyone is still striving to come to terms with is the apparent underperformance of modern crossbow reproductions, and the choice of high power low powerstroke crossbows by our ancestors.

But a few thoughts occurred to me:

I tend to agree that it must have something to do with the metal used. Modern spring steel is not a normal carbon steel. It is infused with other elements particularly silicon to improve its elasticity. You could get away with far higher draw lengths for a given prod length with modern spring steel - and modern crossbows reflect this. OTOH, to use that material with the same draws as a medieval crossbow would be an inefficient use of the material. I suspect that spring steels property of elasticity would be counterproductive at these short powerstrokes it would, I suspect, make a lazier bow.

Secondly when people nowadays quench and temper spring they tend to aim for uniformity. Same hardness right through. But we all know medieval swords are best when a little softer in the core and medieval armour softer at the back than on the front. And we know they made things this way deliberately. Why then not crossbow staves? A steel prod hardened in front and soft at the back would mimic a composite in many ways. If they did this, what impact would it have on a steel bows efficiency?

Cheers,

Joseph

But a few thoughts occurred to me:

I tend to agree that it must have something to do with the metal used. Modern spring steel is not a normal carbon steel. It is infused with other elements particularly silicon to improve its elasticity. You could get away with far higher draw lengths for a given prod length with modern spring steel - and modern crossbows reflect this. OTOH, to use that material with the same draws as a medieval crossbow would be an inefficient use of the material. I suspect that spring steels property of elasticity would be counterproductive at these short powerstrokes it would, I suspect, make a lazier bow.

Secondly when people nowadays quench and temper spring they tend to aim for uniformity. Same hardness right through. But we all know medieval swords are best when a little softer in the core and medieval armour softer at the back than on the front. And we know they made things this way deliberately. Why then not crossbow staves? A steel prod hardened in front and soft at the back would mimic a composite in many ways. If they did this, what impact would it have on a steel bows efficiency?

Cheers,

Joseph

| Joseph Gora wrote: |

| I tend to agree that it must have something to do with the metal used. Modern spring steel is not a normal carbon steel. It is infused with other elements particularly silicon to improve its elasticity. You could get away with far higher draw lengths for a given prod length with modern spring steel - and modern crossbows reflect this. OTOH, to use that material with the same draws as a medieval crossbow would be an inefficient use of the material. I suspect that spring steels property of elasticity would be counterproductive at these short powerstrokes it would, I suspect, make a lazier bow.

Secondly when people nowadays quench and temper spring they tend to aim for uniformity. Same hardness right through. But we all know medieval swords are best when a little softer in the core and medieval armour softer at the back than on the front. And we know they made things this way deliberately. Why then not crossbow staves? A steel prod hardened in front and soft at the back would mimic a composite in many ways. If they did this, what impact would it have on a steel bows efficiency? |

The short answer is that it would have no effect.

The key point is that the heat treatment has almost no effect on the elastic modulus of the steel. What spring tempering does is let the steel be strained more and still be able to return back to the original shape. Harder than the spring temper, and it'll be just as easy, and just as hard, to bend the piece of steel by, say, 3 degrees. But bend it far enough, and the harder steel with fracture, while the spring tempered steel will survive (and spring back). Softer than the spring temper, and it'll stay bent at a point where the spring steel will still spring back.

(The alloy has almost no effect on the elastic modulus as well, for most steels. Wrought iron through to very high carbon steels, special spring steel alloys, etc. all have almost the same elastic modulus. Even most stainless steels have an elastic modulus close to that of carbon steels, despite being 15-30% non-iron.)

But perhaps something can be done by differential hardness of a steel prod. With a D-shaped cross section, with flat back (your "front"?) and rounded belly, with the rounded side, which will be under compression, being harder, might work. You do not want to over-strain the back of a too-hard prod, which is under tension. Cracks starting on the back are likely to cause catastrophic failure, while cracks on the belly are much more benign.

So you want to strain the belly more, and a D-section will do this. I don't know if you get benefit from an extra-hard belly, but you might.

Thanks for the reply, Timo.

I was just looking at the property of elasticity of various steels. I did not know that alloys had so little effect on this - although some research papers a quick google found might suggest the consistency of the elastic modulus has been exaggerated, I still don't think they are talking about differences that would really matter to us. Memo to me to do more research before posting!

My other suggestion is a stab (shot?) in the dark, really. But given precisely what you have just established, the same elastic modulus throughout the prod would eliminate (I would think) any real comparison to a composite sinew/horn bow. Oh well...

What else then could we be missing?

I was just looking at the property of elasticity of various steels. I did not know that alloys had so little effect on this - although some research papers a quick google found might suggest the consistency of the elastic modulus has been exaggerated, I still don't think they are talking about differences that would really matter to us. Memo to me to do more research before posting!

My other suggestion is a stab (shot?) in the dark, really. But given precisely what you have just established, the same elastic modulus throughout the prod would eliminate (I would think) any real comparison to a composite sinew/horn bow. Oh well...

What else then could we be missing?

Page 16 of 19

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum