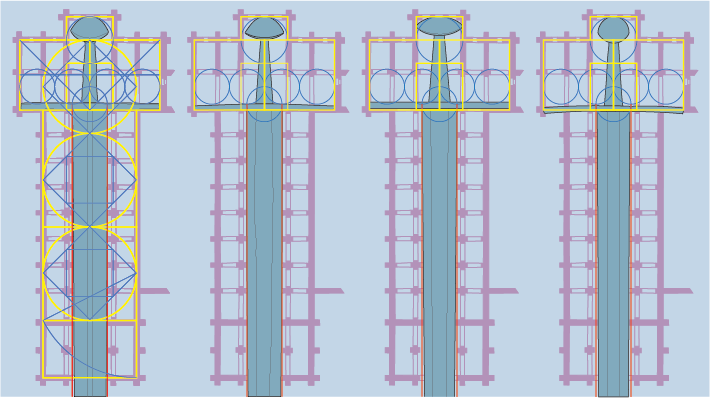

In a very different way, Peter's theories on sword geometry are inspiring. Me and my buddies are currently building a HEMA club in our city, and I'm working on our logo...

... and we are thinking of putting a sword with proportions as a background. The first resulting drawings are pretty neat!

| Niels Just Rasmussen wrote: | ||

Hi Mark. Interesting that the sword from the Christensen collection also shows an asymmetrical crossguard that doesn't really fit the geometry - just like on the Esrum sword! So do we have a later repair/fix on the crossguard here as well since they also here, as the Esrum sword - are "flaring" out. But to see the inscribed hexagon (a perfect number 6) outlined by the exact pommel shape makes you think -> is it that shape because of function and/or because the need to make a hexagon?! With Christ you have an octagon and square around his eye connected with his right hand (and the divine halo circle within the square is already painted from the start). Still a good result, even if no Pythagoras ;) |

I do not think the fact that the guard is not perfectly true suggests that the guard fails to conform to the geometry. Rather it is a result of the process of making. Swords are often asymmetrical. When you consider how swords were made this is not so strange. The asymmetry of medieval swords exist not because the makers were unable to produce more symmetrical work but rather a result of the division of labour between different workshops and craftsmen and time constrains, I would think.

Guards that are askew or off to one side are more the norm than an exception.

If we allow ourselves to centre the guard from its now of centre position, I suspect it form and proportion will conform well to the grid.

You also see this rather carefree attitude to precise dimensions and symmetry in other arts and crafts of the period. In all these arts we can see proportion and underlying structure being a fundamental element.

This combination of less than perfect symmetry together with coherent and commensurable proportions is in fact one good argument for that geometric and/or modular principles were used as design tools.

As an example of possible inherent symbolic meaning of the geometry of a sword design there is a short text about a sword found at Søborg (available online as a PDF).

(http://albion-swords.com/images/swords/johnsson/Soeborg/SoeborgTeaser.pdf)

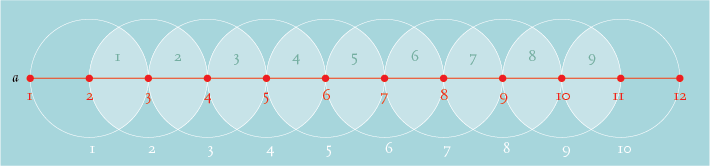

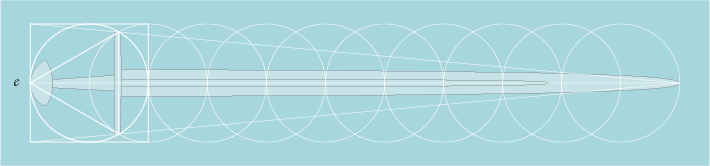

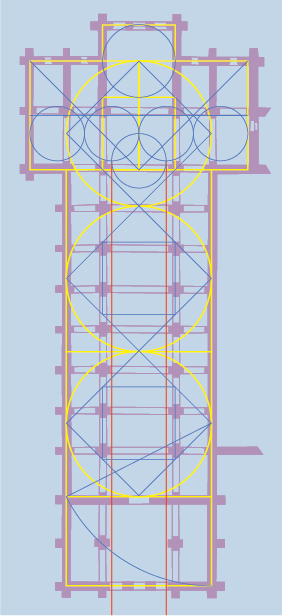

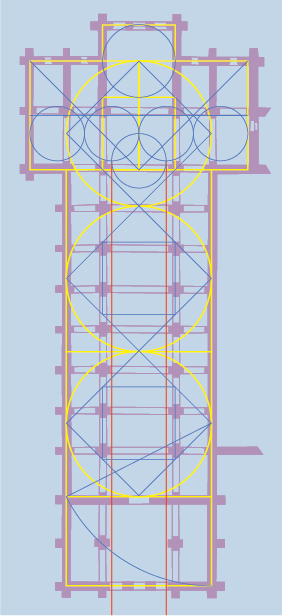

The proportions of this sword can be defined by a series of 10 circles (a type II structure where the guard is placed in the middle of the first vesica). The 10 circles marks the line in 12 points, creating 9 vesica shapes. The numbers 10, 12 and 9 are of course deeply meaningful in the medieval understanding of reality as reflected in the holy mysteries and Creation and so it is perhaps not far fetched to suggest that these symbolic meanings were also fundamental elements of the design.

-10 is among other things the Commandments, 12 are the Disciples and 9 is Thrice Holy and the Hierarchy of Angels.

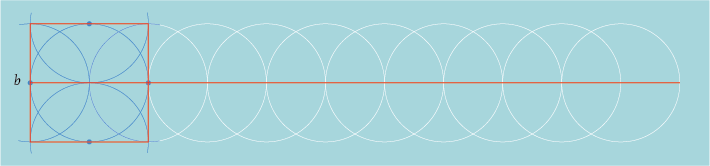

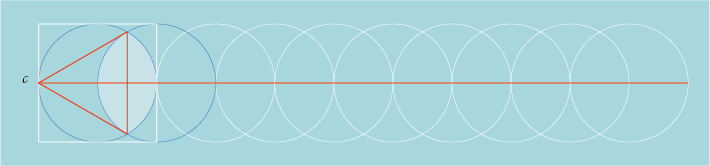

The hilt is defined in the first circle of the series together with a square and an equilateral triangle. Each by themselves, these forms carry meaning, but that might also be considered in combination. If the sword is "Verbum Dei" (the word of God) it is only fitting that its hilt is defined by the shape that signifies Trinity. The square is Righteousness (as Clemens of Alexandria tells us) but also Stability and the framework of the physical world (the four corners of the compass and the four humors of man).

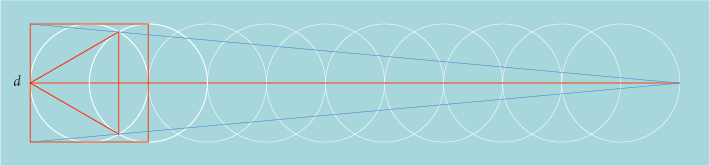

The proportions of the structure is in itself interesting. You can draw a straight line from the corner of the square, via the corner of the triangle and it will meet the midline of the structure at the periphery of the last circle. Even though this is not mathematically exact, the discrepancy is so small (0,2 mm) that it would be hidden within the thickness of the lines if drawn to full scale. Such discrepancies are almost to be expected when you construct geometry with compass and straight edge and would be very difficult to tell apart from other flaws in the lay out. Medieval designers did not calculate the geometry but rather constructed it directly. It is therefore quite possible that the diagonal line that unites the square and the triangle with the beginning and end of the construction carried the meaning of "Alpha and Omega" (I Am the Beginning and the End).

The hilt of the sword is defined by geometric cuts of the square in combination with the original circle.

The width of the blade is defined by two tangent arcs that cut the side of the square in the proportion of the golden section (this particular cut occurs fairly commonly in the analysis I have done).

A note on analysis of proportion and geometric construction:

When we do this kind of backwards engineering of a design method, through the analysis of art and artefacts it is important to observe some rules. Even if we cannot know exactly what the original methods were or what kind of rules they followed (even though we know there *were* rules to follow!) we can at least now that they followed Euclidian principles. Any element that is added to the structure must be defined by elements that already exist in the structure. A new geometric form must be constructed from ell defined points that are already present. The diameter of a circle or the sides of and octagon cannot hover unrelated to the rest of the structure: they must be "grounded" in the existing grid.

This poses a rather severe stricture on the analysis. A proportion or form must not only meet the dimensions of a geometric form, it must do so in a way that completes the overall structure. Using geometry as a tool for design will define both proportion and position of each element simultaneously.

Last edited by Peter Johnsson on Tue 13 Dec, 2016 3:09 am; edited 2 times in total

Below, another observation about the layers of possible symbolic meaning inherent in geometric constructions. Two circles that are drawn so that their peripheries cut through each others centres create a vesica. The vesica was in itself a symbol for the generative force, rebirth and transformation.

We have reason to believe that two circles combined in such a way among other things signified Heave and Earth as the Lord´s Dominion, the totality of creation.

Chirst in Majesty on his heavenly throne is often depicted in a vesica shaped halo, sitting on the rainbow or an arc.

From the two circles and the vesica several important forms can be derived. The vesica is naturally also the Fish, "ICHTUS" or (Iesous Christos Theou Uios Soter: Jeusus Christ God´s Son Saviour).

That the vesica was seen as a symbol for generative power of the pregnant woman is not a new age fantasy. It is supported in medieval art. The Vesica is therefore a symbol for birth and resurrection and is also associated with the Virgin.

A number of important symbols can be derived with the geometry of the square, circle and vesica. The underlying geometric structure is important for the form far beyond being a method to organise proportions in an aesthetically pleasing way.

Attachment: 28.73 KB

Attachment: 28.73 KB

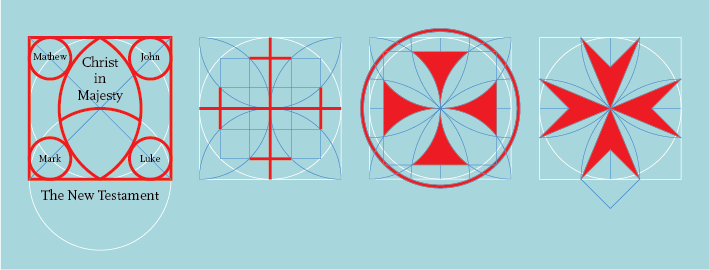

Some central ideas of the Cristian faith expressed by the geometry of the combined circles and the vesica.

Attachment: 223.05 KB

Attachment: 223.05 KB

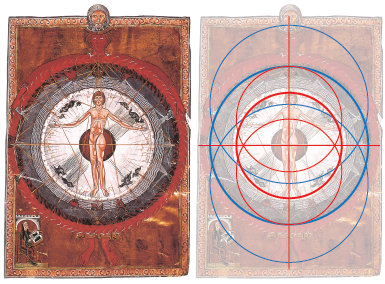

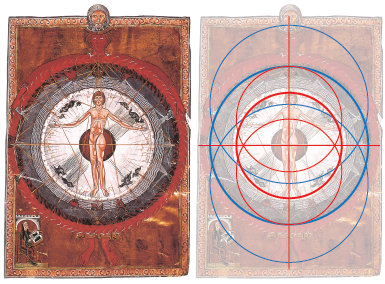

Microcosm and macrocosm illustrated in a way so that the geometric proportions of the lay out express the symbolism of the image. Man is in harmonic proportion to Creation. Being defined by a circle, also in the image of God.

Attachment: 40.26 KB

Attachment: 40.26 KB

Mary and Elisabeth greeting each other. The vesica shaped windows show they are pregnant with Jesus and John.

Attachment: 49.52 KB

Attachment: 49.52 KB

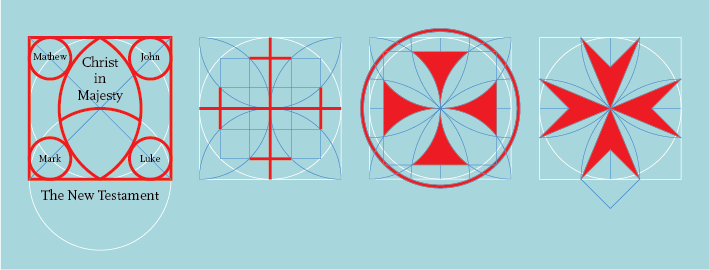

Illuminations of the New Testament is often layer out in a way that combine geometric forms in significant ways.

Some common cruciform emblems may involve geometric proportions.

We have reason to believe that two circles combined in such a way among other things signified Heave and Earth as the Lord´s Dominion, the totality of creation.

Chirst in Majesty on his heavenly throne is often depicted in a vesica shaped halo, sitting on the rainbow or an arc.

From the two circles and the vesica several important forms can be derived. The vesica is naturally also the Fish, "ICHTUS" or (Iesous Christos Theou Uios Soter: Jeusus Christ God´s Son Saviour).

That the vesica was seen as a symbol for generative power of the pregnant woman is not a new age fantasy. It is supported in medieval art. The Vesica is therefore a symbol for birth and resurrection and is also associated with the Virgin.

A number of important symbols can be derived with the geometry of the square, circle and vesica. The underlying geometric structure is important for the form far beyond being a method to organise proportions in an aesthetically pleasing way.

Some central ideas of the Cristian faith expressed by the geometry of the combined circles and the vesica.

Microcosm and macrocosm illustrated in a way so that the geometric proportions of the lay out express the symbolism of the image. Man is in harmonic proportion to Creation. Being defined by a circle, also in the image of God.

Mary and Elisabeth greeting each other. The vesica shaped windows show they are pregnant with Jesus and John.

Illuminations of the New Testament is often layer out in a way that combine geometric forms in significant ways.

Some common cruciform emblems may involve geometric proportions.

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

|

The width of the blade is defined by two tangent arcs that cut the side of the square in the proportion of the golden section (this particular cut occurs fairly commonly in the analysis I have done). |

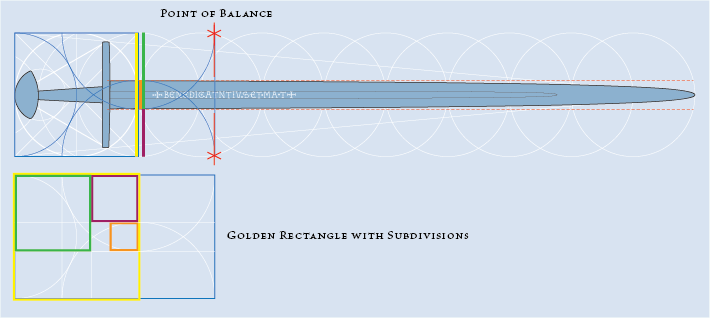

This one particular detail was not clear to me until now - previously I had been trying to use only arcs based on the diameter of the basic circle. That last diagram showing the subdivisions of the Golden Rectangle is very helpful! I think this construction really improved the next diagram I was about to share...

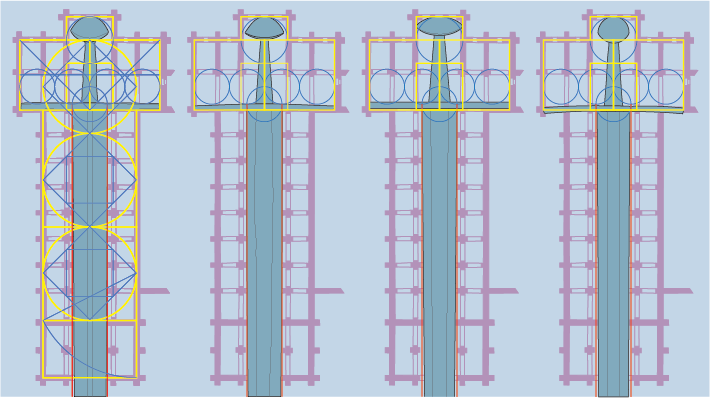

I went back to revise my diagram of the broad sword from Brussels, and found that another sword from Christensen's collection (and formerly Boissonas') matches it's length almost exactly. Both have the same structure and primary ratio of 3:19 as the Soborg sword, as can be confirmed from the published measurements (another correction to my first post.)

[ Linked Image ]

The Boissonas sword is more similar to the Soborg sword with the width of the blade based on the Golden Rectangle, and the hilt forms another. It and the Brussels sword both have blades that are approximately one fifth the width of the cross.

The extra wide cross and blade of the latter don't seem to be based on any Golden Rectangle however... instead I've suggested arcs based on a 5:6 rectangle that is commensurate with the width of the blade, and seems to be compatible with other geometric elements.

[ Linked Image ]

The Soborg sword really seems exceptional in how consistent every element is with the overall design!

Mark, I cannot really express how wonderful it is to see you perform this analysis with results that are so parallel to what I have come across. Even more so because I have only published a small part of the material and have yet to describe many important details. You have not simply copied stuff or tried to force a square peg in a round hole. You show many of the same strategies I have found but in other swords and from your own conclusions.

I will return with some more observations and comments later.

-I just had to get this of my chest :-)

I will return with some more observations and comments later.

-I just had to get this of my chest :-)

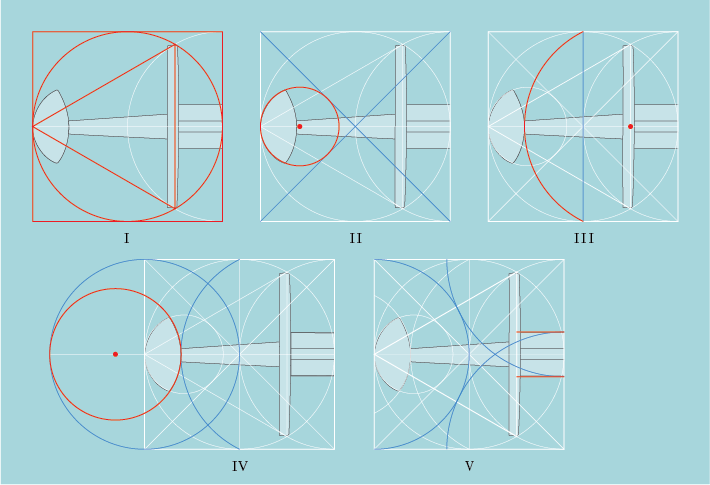

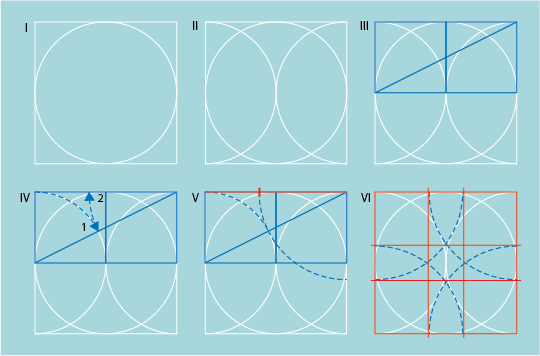

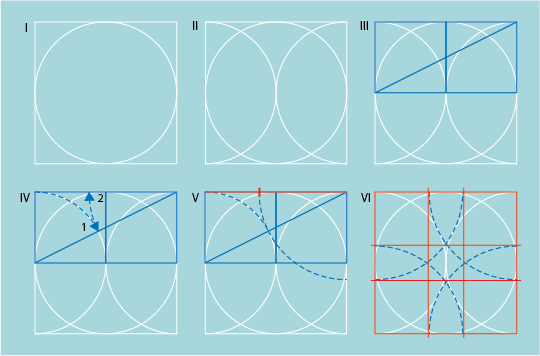

This diagram might be helpful in explaining how the golden section can be performed in a square.

At some time I came to realise that the classic way to construct the golden section from two squares and their diagonal, was already built in to the square and circle. If you make a diagonal across *half* the width of the square, it is the same as a diagonal across two squares. The arc you draw to cut the diagonal, is already present in the radius of the basic circle.

The arc you project from the diagonal is an arc that is tangent to the basic circle.

That way, the square and the circle are together a kind of golden section calculator :-)

To me this was a revelation of sorts.

I may be slow sometimes, but when the apple finally falls into your hand it is oh so sweet. :-)

Attachment: 31.01 KB

Attachment: 31.01 KB

At some time I came to realise that the classic way to construct the golden section from two squares and their diagonal, was already built in to the square and circle. If you make a diagonal across *half* the width of the square, it is the same as a diagonal across two squares. The arc you draw to cut the diagonal, is already present in the radius of the basic circle.

The arc you project from the diagonal is an arc that is tangent to the basic circle.

That way, the square and the circle are together a kind of golden section calculator :-)

To me this was a revelation of sorts.

I may be slow sometimes, but when the apple finally falls into your hand it is oh so sweet. :-)

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

|

I do not think the fact that the guard is not perfectly true suggests that the guard fails to conform to the geometry. Rather it is a result of the process of making. Swords are often asymmetrical. When you consider how swords were made this is not so strange. The asymmetry of medieval swords exist not because the makers were unable to produce more symmetrical work but rather a result of the division of labour between different workshops and craftsmen and time constrains, I would think. Guards that are askew or off to one side are more the norm than an exception. You also see this rather carefree attitude to precise dimensions and symmetry in other arts and crafts of the period. In all these arts we can see proportion and underlying structure being a fundamental element. This combination of less than perfect symmetry together with coherent and commensurable proportions is in fact one good argument for that geometric and/or modular principles were used as design tools. As an example of possible inherent symbolic meaning of the geometry of a sword design there is a short text about a sword found at Søborg (available online as a PDF). (http://albion-swords.com/images/swords/johnsson/Soeborg/SoeborgTeaser.pdf) |

Hi Peter.

Thanks for all this fantastic information on the Søborg Sword and how the guard asymmetry is not unusual.

When I think about it you are probably very correct to be prudent, as those who have already tried earlier to delve into sacred geometry of landscape and churches have been ridiculed by academics -> mostly based on their focus on possible involvement of Templar Knight in their hypotheses. I'm talking about Henry Lincoln (The Holy Place - about Rennes le Chateau) and Erling Haagensen on the placement of churches on Bornholm in a geometric pattern.

I'm not skilled enough to evaluate if their geometric results are correct, but to me it does actually seem that they follow the guideline you gave here Peter: "Any element that is added to the structure must be defined by elements that already exist in the structure. A new geometric form must be constructed from well defined points that are already present. The diameter of a circle or the sides of and octagon cannot hover unrelated to the rest of the structure: they must be "grounded" in the existing grid." Another project for Mark, perhaps :lol:

The problem is more their involvement of the Templar Knights, who as a group we have basically no evidence for in Denmark (inc. Bornholm) - Sweden have it's own "Templar rage" with the Arn books and movie - but what people tend to forget is the huge involvement of Cistercian monks in Denmark (and Sweden) in the second half of 1100 and 1200's. So some academics use the lack of evidence for Templar's as the focus to knock down basically ALL their data, the geometric findings as well.

But here are some historical informations, which really are food for thought:

Esrum Kloster is for instance a daughter cloister of Clairvaux itself (established with monks from Clairvaux) and St. Bernard of Clairvaux and Archbishop Eskil of Lund were personal friends and Eskil was buried in Clairvaux. St. Bernard did actually wrote the (latin) Rule of the Templar Order, so that is perhaps the "red herring" that makes people see Knights Templar's as those doing geometric "secrets", when the Cistercians (or even other monk-orders brought up from Europe by Eskil) are the obvious candidates to me at least when it comes to Bornholm's possible geometric church layout.

It is VERY interesting that the "most geometric" sword you have found so far is the Søborg sword that could very well be connected with Eskil of Lund or his successor Absalon (who was with all likelihood educated in Paris - so another French connection). A sword like that must have been a very deliberate construction and given/ordered by a man with both a high status and a sense for the geometric. How many people in Denmark could that have been in the late 1100 early 1200?

It could basically only be the leading Herremænd - the Thrugot family (including Archbishops of Lund: Asser & Eskil) or the Hvide family (Archbishops of Lund: Absalon & Anders Sunesen) who send their sons to be educated in the major learnings centers of Europe. Especially the abbey schools of Sainte-Geneviéves og Saint-Victors in Paris were popular among danes from the second half of the 1100's

Arnold of Lübeck writes this in 1212 these highly interesting things about Danes - both warfare, trade and education:

“ The Danes having for a long time carried on an extensive trade with Germany, have adopted the arms and dress

used by other nations. Formerly they were clothed in the garb of mariners, because the nation was always engaged

in expeditions by sea. Now they are luxuriously dressed in stuffs of various colours, and even purple and fine linen. The

source of their riches is the fishery on the coast of Scania, which is frequented by the vessels of all nations, who

exchange their most valuable wares for the fish which the divine goodness so liberally bestows upon this people.

The country of the Danes is also full of fine horses, fed in their fertile pastures ; and they distinguish themselves in

war by their cavalry as well as naval armaments. They have besides made no inconsiderable progress in learning.

The nobility of that country are accustomed to send their sons to Paris, to be instructed in the learning necessary for

the ecclesiastical profession as well as civil life. In this manner they have acquired a thorough knowledge of the French

tongue, and have become well versed in theology and the belles-lettres ; and as they have a natural aptitude for study,

have be come not only subtle logicians, but able canonists, and deeply versed in the learning necessary for the

management of ecclesiastical affairs. Lastly, religion flourishes eminently among the Danes, as one may judge by

the great numbers of convents of monks of various orders founded by the Archbishop of Lund, the pious Eskill, who,

after resigning all his dignities, retired to finish his holy life in the monastery of Clairvaux."

Monks would not carry swords around (?), but Scandinavian Archbishops and Bishops certainly would be very martial and expected to arrive in full battle gear with their knights, if the king called for a leding (actually stated in the Valdemar II Sejr's Law of Jutland from 1241, and several bishops also died on the battlefield of Fotevik in 1134).

So you don't need warrior monks like Templars to explain "martial christianity" when it comes to Scandinavia, since the church members were from martial families conducting both offensive and defensive warfare.

Danish Archbishops and Bishops were also often OFFICIALLY married (they have to keep the family line going) - Archbishop Eskil was married and had a daughter.

Esrum Kloster is around 5-6 km from Søborg Castle. The castle was given by the King to the Bishop of Roskilde. Under Eskil that would actually be Absalon!

A sword of quality like the Søborg Sword would most likely have been owned by an Archbishop or Bishop or at least a knight attached to these leading men (a prominent Thrugot or Hvide member himself?).

Niels, thank you for more valuable details about Denmark in the time of the Søborg sword! It gives more depth to the picture and I am happy to hear how your thoughts align with mine. :-)

Geibig can help us with dating the sword which will place it as contemporary to the arch bishop Eskil.

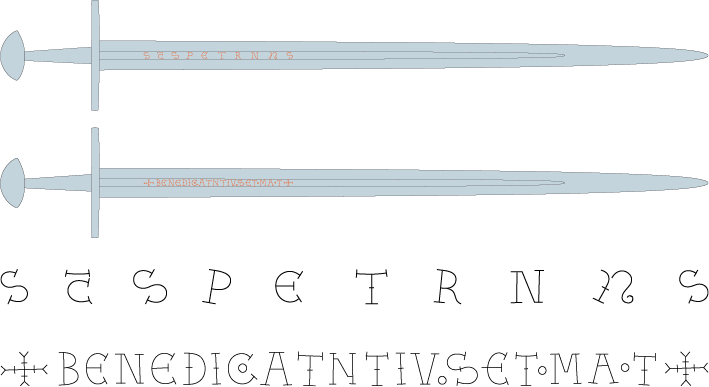

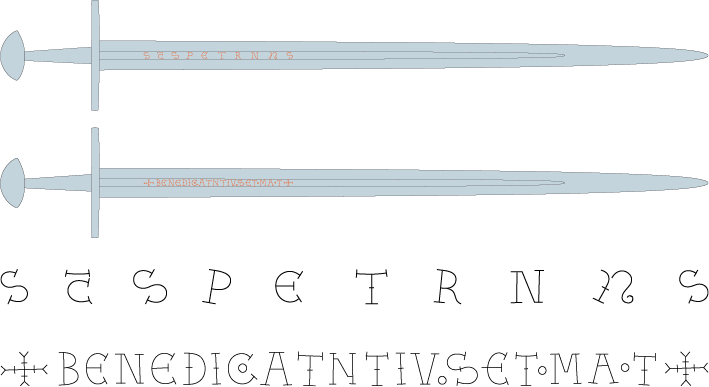

From my short text introducing the Søborg sword: "The blade conforms to type 9 (a type that was in use during the 12th century) and the hilt is of combination type 16 variant 1 (mid 10th century to the third quarter of the 12th century). A further basis for dating is the inscription that according to Geibig is of a type that is in use from the mid 11th century to the end of 12th century. This suggests a span for dating from around AD 1100 - 1175 for Søborg D 8801."

And further: "The inscriptions in the fullers show that its owner viewed his weapon and his role as a warrior in a religious perspective. The lettering is

cryptic, but part of its meaning might be descipherable. The first part of the inscription is probably a prayer for blessing from someone upon "Us" since the N after BENEDICoAT could indicate "Nos". TIoSEToMAoT could be an acronym for a saint (or saints) or religious persona(- s). MA(oT) towards the end might stand for "Mater" or "Maria".

The inscription "SctSPETRNnuS" on the other side is probably an invocation to Saint Peter, the protector of the Catholic Church.

In its time it would have belonged to a man of means and power. It was a weapon that vouched for his martial prowess, his sense of duty as well as his privileges. It did not express its owner ́s status through any gold or silver on the hilt but through a stark form that shows a dedication to severe knightly ideals."

...and:" This was a period when the political necessities of kings

clashed dramatically with the interests of the Holy See. Eskil took active part in the internal conflicts of the kingdom as well as the powerstruggle within the Church. As a loyal follower of Pope Alexander III, he put the interests of the Catholic church before those of the Danish monarchy. He was also much in favor of the Cistercian order and it expanded its influence during this time period.

The inscriptions in the fullers of ther Søborg sword makes clear that it was a weapon intended for a holy purpose and that its owner most probably favored the cause of the Catholic church. If we let our imagination have some free rein it is not difficult to imagine that the original owner could have been a man at arms in the service of Archbishop Eskil."

It is naturally also a possibility that the sword belonged to the bishop himself, but I have refrained from suggesting that ;-)

Attachment: 20.93 KB

Attachment: 20.93 KB

Geibig can help us with dating the sword which will place it as contemporary to the arch bishop Eskil.

From my short text introducing the Søborg sword: "The blade conforms to type 9 (a type that was in use during the 12th century) and the hilt is of combination type 16 variant 1 (mid 10th century to the third quarter of the 12th century). A further basis for dating is the inscription that according to Geibig is of a type that is in use from the mid 11th century to the end of 12th century. This suggests a span for dating from around AD 1100 - 1175 for Søborg D 8801."

And further: "The inscriptions in the fullers show that its owner viewed his weapon and his role as a warrior in a religious perspective. The lettering is

cryptic, but part of its meaning might be descipherable. The first part of the inscription is probably a prayer for blessing from someone upon "Us" since the N after BENEDICoAT could indicate "Nos". TIoSEToMAoT could be an acronym for a saint (or saints) or religious persona(- s). MA(oT) towards the end might stand for "Mater" or "Maria".

The inscription "SctSPETRNnuS" on the other side is probably an invocation to Saint Peter, the protector of the Catholic Church.

In its time it would have belonged to a man of means and power. It was a weapon that vouched for his martial prowess, his sense of duty as well as his privileges. It did not express its owner ́s status through any gold or silver on the hilt but through a stark form that shows a dedication to severe knightly ideals."

...and:" This was a period when the political necessities of kings

clashed dramatically with the interests of the Holy See. Eskil took active part in the internal conflicts of the kingdom as well as the powerstruggle within the Church. As a loyal follower of Pope Alexander III, he put the interests of the Catholic church before those of the Danish monarchy. He was also much in favor of the Cistercian order and it expanded its influence during this time period.

The inscriptions in the fullers of ther Søborg sword makes clear that it was a weapon intended for a holy purpose and that its owner most probably favored the cause of the Catholic church. If we let our imagination have some free rein it is not difficult to imagine that the original owner could have been a man at arms in the service of Archbishop Eskil."

It is naturally also a possibility that the sword belonged to the bishop himself, but I have refrained from suggesting that ;-)

The abbey of Fontenay was built by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who was deeply involved with the founding of the order of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon (the Templars).

The Fontanay abbey still exists with many of its original buildings still intact. The monks of this abbey were among other things known for their iron work. A smithy survives where the (one of?) oldest surviving water powered hammers is situated. The hammer was powered from the overflow of water from the fish pond. The smithy is huge: like sizeable church. There is only one black smith hearth surviving, however. Either there were more hearths originally, that have later been removed, or there ere other activities in the smithy that did not require heating of iron. A favourite fantasy of mine is naturally that they forged swords for the crusaders in this smithy, but there is no evidence for this being the case.

The cistecians were well known for their deep interest in geometry.

St Bernard famously said: "No decoration, only proportion" about how churches should be built.

When we take a closer look at the proportions of the abbey church of Fontenay it seems that its plan conforms to a simple geometric lay out.

(It should be noted that my analysis below is simply made from published plans of the abbey church, and therefore at best a suggestion.)

12th century swords have a likeness in the severe but sublime aesthetics of ecclesiastic buildings of the same period. The wide guards and the short grips undeniably have something romanesque or early gothic about them.They also show the same commensurable proportions of contemporary church architecture, combining simple geometric relations and modular ratios.

Making an overlay of some swords over the plan of the abbey church of Fontenay makes for some striking correlations. This is naturally not proof of anything, but perhaps something to reflect on at least.

Attachment: 36.86 KB

Attachment: 36.86 KB

Attachment: 61.79 KB

Attachment: 61.79 KB

The Fontanay abbey still exists with many of its original buildings still intact. The monks of this abbey were among other things known for their iron work. A smithy survives where the (one of?) oldest surviving water powered hammers is situated. The hammer was powered from the overflow of water from the fish pond. The smithy is huge: like sizeable church. There is only one black smith hearth surviving, however. Either there were more hearths originally, that have later been removed, or there ere other activities in the smithy that did not require heating of iron. A favourite fantasy of mine is naturally that they forged swords for the crusaders in this smithy, but there is no evidence for this being the case.

The cistecians were well known for their deep interest in geometry.

St Bernard famously said: "No decoration, only proportion" about how churches should be built.

When we take a closer look at the proportions of the abbey church of Fontenay it seems that its plan conforms to a simple geometric lay out.

(It should be noted that my analysis below is simply made from published plans of the abbey church, and therefore at best a suggestion.)

12th century swords have a likeness in the severe but sublime aesthetics of ecclesiastic buildings of the same period. The wide guards and the short grips undeniably have something romanesque or early gothic about them.They also show the same commensurable proportions of contemporary church architecture, combining simple geometric relations and modular ratios.

Making an overlay of some swords over the plan of the abbey church of Fontenay makes for some striking correlations. This is naturally not proof of anything, but perhaps something to reflect on at least.

This is awesome. I'll definitely go to Fontenay one day (it is not so far from my parent's home by the way)...

I saw you talked about rapiers some posts ago. As I'm deeply into rapiers (mainly end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century) I tried to see historical specimens, mainly in the Musée de l'Armée (they have an incredible collection). Some of them, like one I saw in the Musée Renaissance in Écouen, are very huge: the said Écouen one was 149cm of full length, with a ca. 135cm blade.

I have tried to look on the subject of the rapier to choose according to its own body proportions, but I never thought about the sword proportions themselves. Have you got an exemple of a rapier of this time with proportions?

I saw you talked about rapiers some posts ago. As I'm deeply into rapiers (mainly end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century) I tried to see historical specimens, mainly in the Musée de l'Armée (they have an incredible collection). Some of them, like one I saw in the Musée Renaissance in Écouen, are very huge: the said Écouen one was 149cm of full length, with a ca. 135cm blade.

I have tried to look on the subject of the rapier to choose according to its own body proportions, but I never thought about the sword proportions themselves. Have you got an exemple of a rapier of this time with proportions?

An interesting detail about the Søborg sword is that we have illustrations in a contemporary manuscript of swords that look very similar in appearance to it.

Medieval manuscripts are problematic as visual evidence for swords because the illustrations frequently are less than exacting. However, there is a manuscript that shows swords which nevertheless look strikingly similar to the Søborg. That manuscript is ThULB Ms. Bos. q.6 Chronicle of Otto of Freising.

Manuscript Miniatures gives its date as between 1157 to 1185 AD, meaning it falls within the range of dates predicted by Peter for the real Søborg sword. In folio 68 recto, there is an image of the warring sons of Louis the Pious, namely Charles the Bald, Lothair and Louis II, all represented as contemporary 12th century knights. Their swords look unmistakably similar to the Søborg. First, the swords all have Brazil nut pommels, and the triangular shape is suggestive of a Type A Brazil nut. Secondly, the swords all have blades of longer proportions, yet without being particularly wide. Third, they have narrow fullers (shown with a line) in which there is inlay, and the impression given is of a fairly long inscription. Last, they have a moderately wide rectangular cross, although it must be noted that medieval artists are not known for illustrating Gaddhjalt-type cross guards, which could also be found on swords from this time.

Clearly, the images in this manuscript could be representative any number of 12th century swords, and not just the Søborg. However, given the limitations of realism in 12th century art, it is undeniable that the swords here look similar to the Søborg. Cautiously, we might suggest that this particular image provides plausibility to dating a sword like the Søborg a bit more precisely to the second half of the 12th century, during the heart of the reigns of Henry II, Frederick Barbarossa, and Valdemar the Great of Denmark.

Attachment: 126.53 KB

Attachment: 126.53 KB

[ Download ]

Medieval manuscripts are problematic as visual evidence for swords because the illustrations frequently are less than exacting. However, there is a manuscript that shows swords which nevertheless look strikingly similar to the Søborg. That manuscript is ThULB Ms. Bos. q.6 Chronicle of Otto of Freising.

Manuscript Miniatures gives its date as between 1157 to 1185 AD, meaning it falls within the range of dates predicted by Peter for the real Søborg sword. In folio 68 recto, there is an image of the warring sons of Louis the Pious, namely Charles the Bald, Lothair and Louis II, all represented as contemporary 12th century knights. Their swords look unmistakably similar to the Søborg. First, the swords all have Brazil nut pommels, and the triangular shape is suggestive of a Type A Brazil nut. Secondly, the swords all have blades of longer proportions, yet without being particularly wide. Third, they have narrow fullers (shown with a line) in which there is inlay, and the impression given is of a fairly long inscription. Last, they have a moderately wide rectangular cross, although it must be noted that medieval artists are not known for illustrating Gaddhjalt-type cross guards, which could also be found on swords from this time.

Clearly, the images in this manuscript could be representative any number of 12th century swords, and not just the Søborg. However, given the limitations of realism in 12th century art, it is undeniable that the swords here look similar to the Søborg. Cautiously, we might suggest that this particular image provides plausibility to dating a sword like the Søborg a bit more precisely to the second half of the 12th century, during the heart of the reigns of Henry II, Frederick Barbarossa, and Valdemar the Great of Denmark.

[ Download ]

| Guillaume Vauthier wrote: |

| This is awesome. I'll definitely go to Fontenay one day (it is not so far from my parent's home by the way)...

I saw you talked about rapiers some posts ago. As I'm deeply into rapiers (mainly end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century) I tried to see historical specimens, mainly in the Musée de l'Armée (they have an incredible collection). Some of them, like one I saw in the Musée Renaissance in Écouen, are very huge: the said Écouen one was 149cm of full length, with a ca. 135cm blade. I have tried to look on the subject of the rapier to choose according to its own body proportions, but I never thought about the sword proportions themselves. Have you got an exemple of a rapier of this time with proportions? |

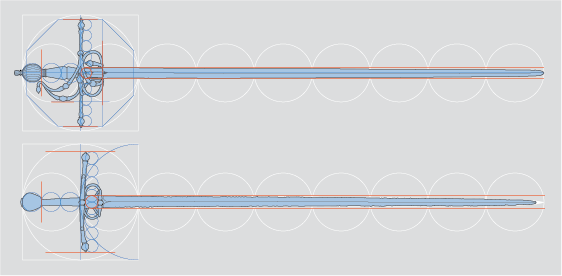

Guillaume, because of the complexity of rapier hilts any geometry that may form the basis for their proportions it will likewise also be complex and because of this perhaps less convincing than the simple beauty that is often the case with the geometry for medieval swords.

Another factor we must factor in is that hilts and blades were much more separate entities in the age of the rapier.

The quote from the play I posted earlier "The Weeding of Covent Garden" specifically mentions a sword with the *mathematical hilt*. I suspect that we will less often find the commensurable proportions that are typical for medieval swords in rapiers. By commensurable, I mean that *all* parts are included in the same structure. All parts combine into a whole.

This idea of wholeness of parts into a harmonious total was very much at the core of medieval religious and aesthetic philosophy.

"When the parts are arranged in this way, they all combine into the whole; so

that out of all the parts in the universe, there emerges one single wholeness of

things"

Thomas of Aquino, AD 1225-1274

However, the hilts of rapiers were possibly made as self sufficient objects, that could and often were mounted with new blades. It might therefore be that case that a geometry that defines the hilt of a rapier hilts will not include the blade (its length and width). The analysis of rapiers I have made so far has non the less yielded some results that encourage further study.

For an example of the geometry of rapiers, see below an analysis of a rapier from the Deutsches Klingenmuseum compared with another from the Royal Armouries in Stockholm. They share some similar elements in their design. This illustration was published in the catalogue for the exhibition "The Sword - Form & Thought" at the Klingenmuseum. If you find this interesting, I recommend that you buy the catalogue from the museum. There might still be a few copies left.

[quote="Craig Peters"][size=12]An interesting detail about the Søborg sword is that we have illustrations in a contemporary manuscript of swords that look very similar in appearance to it.

Medieval manuscripts are problematic as visual evidence for swords because the illustrations frequently are less than exacting. However, there is a manuscript that shows swords which nevertheless look strikingly similar to the Søborg. That manuscript is ThULB Ms. Bos. q.6 Chronicle of Otto of Freising.

/quote]

Craig, thank you for posting this beautiful illumination! It is great to see a contemporary image of the men at arms of this period in this context.

Medieval manuscripts are problematic as visual evidence for swords because the illustrations frequently are less than exacting. However, there is a manuscript that shows swords which nevertheless look strikingly similar to the Søborg. That manuscript is ThULB Ms. Bos. q.6 Chronicle of Otto of Freising.

/quote]

Craig, thank you for posting this beautiful illumination! It is great to see a contemporary image of the men at arms of this period in this context.

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| Niels, thank you for more valuable details about Denmark in the time of the Søborg sword! It gives more depth to the picture and I am happy to hear how your thoughts align with mine. :-)

Geibig can help us with dating the sword which will place it as contemporary to the arch bishop Eskil. From my short text introducing the Søborg sword: "The blade conforms to type 9 (a type that was in use during the 12th century) and the hilt is of combination type 16 variant 1 (mid 10th century to the third quarter of the 12th century). A further basis for dating is the inscription that according to Geibig is of a type that is in use from the mid 11th century to the end of 12th century. This suggests a span for dating from around AD 1100 - 1175 for Søborg D 8801." And further: "The inscriptions in the fullers show that its owner viewed his weapon and his role as a warrior in a religious perspective. The lettering is cryptic, but part of its meaning might be descipherable. The first part of the inscription is probably a prayer for blessing from someone upon "Us" since the N after BENEDICoAT could indicate "Nos". TIoSEToMAoT could be an acronym for a saint (or saints) or religious persona(- s). MA(oT) towards the end might stand for "Mater" or "Maria". The inscription "SctSPETRNnuS" on the other side is probably an invocation to Saint Peter, the protector of the Catholic Church. In its time it would have belonged to a man of means and power. It was a weapon that vouched for his martial prowess, his sense of duty as well as his privileges. It did not express its owner ́s status through any gold or silver on the hilt but through a stark form that shows a dedication to severe knightly ideals." ...and:" This was a period when the political necessities of kings clashed dramatically with the interests of the Holy See. Eskil took active part in the internal conflicts of the kingdom as well as the powerstruggle within the Church. As a loyal follower of Pope Alexander III, he put the interests of the Catholic church before those of the Danish monarchy. He was also much in favor of the Cistercian order and it expanded its influence during this time period. The inscriptions in the fullers of ther Søborg sword makes clear that it was a weapon intended for a holy purpose and that its owner most probably favored the cause of the Catholic church. If we let our imagination have some free rein it is not difficult to imagine that the original owner could have been a man at arms in the service of Archbishop Eskil." It is naturally also a possibility that the sword belonged to the bishop himself, but I have refrained from suggesting that ;-) |

Hi Peter.

Is is possible that a person receiving this sword in the younger parts of his life could have carried it into old age (so into very early part of 1200), so that is why Absalon is still also a possible candidate as would his brother Esbern Snare.

If the sword had been found at the Cistercian Esrum Kloster, then the Eskil connection would have been more secure, but it is the question of finding it at Søborg Castle, that makes for a possible Hvide connection as well.

So here I will start with the Hypothesis A - tying the sword to Eskil.

The Thrugot family:

The Jutish Herremand Thorkil (called Svend) Thrugotsen - (son of Thrugot Ulfsen "fagrskinna") had been part of the hird to King Canute IV the Holy (King 1080-1086) and killed with the King in St Albani Kirke during the rebellion in 1086 against the issued poll-tax (when the King was preparing a massive attack to take back the Danish throne in England).

Svend Thrugotsen had a sister - Bodil - who married the Danish King Erik Ejegod (King 1095-1103). They went on pilgrimage and visited Emperor Alexios Komnenos and the Varangian guard in Constantinople in 1103. King Erik died in Cyprus, but Bodil reached the Holy Land before she died as well. The survivors brought home the bones of St. Nikolaos of Myra (the real Santa Claus and patron saint of sailers and students - off course Danes would need that) to Denmark, which the Danish King had received from the Byzantine Emperor.

Svend (Thorkil) Thrugotsen had the following sons: They expanded the family's influence from Jutland, to also include Scania!

Svend Svendsen - Bishop of Viborg. Died on pilgrimage in Jerusalem 1153.

Christian Svendsen - died 1140.

Asser Svendsen (~1055-1137) - Bishop of Lund 1089-1104. Archbishop of Lund 1104-1137.

Aage Svendsen. ? except name ?

Eskil Svendsen "hærfører" (= army commander) - died on Pilgrimage in 1151.

Asser became Bishop of Lund in 1089 and was Regent of Denmark with Harald Kesja in 1103-1104 (while Erik Ejegod was away and until Niels became elected King - 1104-1134).

From 1104-1137 Asser was Archbishop of Lund.

Asser was a supporter of Erik II Emune (King 1134-1137) in the civil war 1131-1134 and Asser participated in the battle of Fotevik in 1134 on the winning side against the forces of Magnus and 5 Bishops who died on the battlefield or later from wounds. [The Bishops are Peder of Roskilde, Thore of Ribe, Ketil of Vestervig, Adelbjørn of Slesvig & Henrik of Sigtuna from Sweden]. King Niels is later in 1134 slain in Slesvig Town.

The civil war had started after Magnus (the son of King Niels) had killed the Duke of Slesvig, Knud Lavard (son of King Erik Ejegod and the father of future King Valdemar I the Great) in 1131. The events was written down in the latin "Roskilde Chronicle" by a pro-Magnus supporter in 1138.

Christian Svendsen has three sons:

Svend Christiansen.

Eskil Christiansen - "our" Archbishop Eskil of Lund (~1100-1181)

Agge Christiansen.

Svend Christiansen had two sons:

Christian Svendsen.

Asser Svendsen - The Dean of Lund.

They were both part of a conspiracy who tried to murder King Valdemar the Great of which we will return to.

Agge Christiansen had one son:

Svend Aggesen - the Danish historian, who wrote the "Brevis Historia Regum Dacie" in 1186-87.

Svend Aggesen wrote that both his father Agge and grandfather Christian fought for Erik II Emune during the civil war 1131-1134 and Svend Aggesen joined the "Thinglid" (Housecarls) of King Valdemar the Great and Canute VI and went on numerous expeditions with them.

He also wrote the "Lex Castrensis" a latin version/retelling of the Witherlogh in 1181-82 (the Hird law of Canute the Great).

Eskil was thus the nephew of Archbishop Asser.

As a young man he is send to Hildesheim in Germany to be educated and at some point he met (or became acquainted through letters) with the ~10 year older St. Bernard of Clairvaux and they became personal friends.

After finishing his education around ~1130 he became the Dean of Lund, while his uncle Asser was Archbishop there.

King Erik II Emune appoints him to become the new Bishop of Roskilde in 1134 (Peder of Rosklde died at Fotevik); but Eskil personally think the new king a dictator.

Together with Peder Bodilsen (we will return to this important person later in another thread) he launches a rebellion on Sjælland against King Erik II Emune, who has to flee the Island. The King returns with a leding army from Jutland and crush the rebellion.

Eskil and Peter Bodilsen escapes this with fines and together in 1135 Eskil and Peder starts the Benedictine monastery at Næstved - later Skovkloster (Herlufsholm).

Just before Erik II Emune's death in 1137, Eskil is named the next Archbishop of Lund because of heavy support from Peder Bodilsen. Eskil has good relations to the next King Erik III Lam and they mint coins together in Lund.

A pretender Oluf Haraldsen (son af Harald Kesja, a bastard son of King Erik I Ejegod) attacked Sjælland and Scania from Sweden and at Ramløse he killed Bishop Rike of Roskilde and either drove Eskil from Lund in 1139 and again in 1140 [it seems Eskil is captured and probably first freed in 1143].

Oluf is declared King of Scania by the Scanians (1140-1143) and he names his own Archbishop of Lund (keeping Eskil in captivity). In 1143 Erik III Lam kills Oluf at the battle at Tjutebro and reconquers the area.

After regaining his freedom and with help send from his friend St. Bernard he starts in 1144 the Monastery of Herrevad in Scania with 12 monks from Citeaux - the mother itself of the Cistercian order. All this is paid by Eskil out of his own pocket.

Robert from Citeaux became the first abbot of Herrevad. Later 9 Cistercian laybrothers arrived to teach the Danes in crafts and agricultural practices of the Cistercians. This could be very essential for our discussion of sacred geometry!

Eskil changed some land with King Erik III Lam and acquired territory at Esrum. After visiting Clairvaux himself he brought back some monks to start the Monastery of Esrum in 1151 to take over a failing Benedictine monastery establish there in 1140.

So further Cistercian French monks arriving in Denmark, who could bring theoretic geometric and craft knowledge.

In 1155 Eskil travels to Rome and get final confirmation that the Danish church is free of Hamburg-Bremen. Norway gets their own Archbishopry of Nidaros (Trondheim), while the Swedish Archbishopy of Uppsala is still under the control of the Danish Archbishopy of Lund.

In his way home Eskil is taken captive by a Burgund Knight (probably by order from Friedrich Barbarossa). First with the help from King Valdemar the Great in 1158 is he released. King Valdemar also appoints Absalon of the Hvide family as Bishop in Roskilde in 1158!

King Valdemar and the Hvide family tries to make friends with Eskil by giving gifts to the Cistercian Order, so Eskil will allow the Danish King to appoint his own Bishops.

In 1160 when the King wants to appoint the new Bishop of Slesvig, Eskil is adamant that the Roman Church should decide and not the Danish King. Eskil has to flee Denmark and in 1161 King Valdemar conquers Eskil's stronghold Søborg Castle. It is likely that the sword can be tied to this event (though it could also be a lake offering before or after).

Eskil had a daughter Asa Eskilsdatter, who had married the Jarl Karl of Halland. They had two sons

Karl Karlsen & Knud Karlsen.

According to Saxo King Valdemar had tried to siege Søborg, but is was dragging out beyond his patience. King Valdemar had gotten hold of Eskil's grandson Karl, who was attending school at Esrum Kloster and threatening to hang him from a gallows in front of Søborg Castle if they didn't surrender. The King also forged a letter (looking like it was written by Eskil) which said that the castle should surrender so Karl wouldn't be killed. Saxo finds this very cunning!

Eskil is finally brought back to Denmark from his exile by Absalon, but it seems that Eskil had to accept that Knud Lavard - the father of King Valdemar the Great - is made into a saint; which Eskil had been very opposed to.

In 1170 at Ringsted Eskil is the one who officially makes Knud Lavard into a saint and crowns both King Valdemar the Great and his son Canute VI.

In 1177 he retires as Archbishop and names Bishop Absalon of Roskilde as his successor and not his own nephew Asser the Dean at Lund.

This is likely because his nephews Asser & Christian Svendsen and his own grandsons Karl Karlsen and Knud Karlsen was part of the conspiracy to kill King Valdemar lead by Magnus a son of King Erik III Lam.

In 1176 they were discovered and Asser spilled all the beans to the King to save his own skin.

Asser & Christian Svendsen was send into exile, while Eskil's grandsons Karl Karlsen and Knud Karlsen went into open rebellion. In 1178 they flee to Sweden, but returns in 1179 with an army, but are both killed on the battlefield in Scania in 1179.

After 1177 where Eskil retired, he moved to Clairvaux living as a Cistercian monk and he died there in 1181 (as around 80 years old). He lived to see both the rise and almost total fall from power of his family, except his nephew and historian Svend Aggesen, who was in the inner circle of King Valdemar the Great as a "housecarl".

But certainly his life was far from boring.

From now on the Hvide family sits on the "Catholic throne" in Denmark.

Last edited by Niels Just Rasmussen on Sun 18 Dec, 2016 10:46 am; edited 6 times in total

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| Below, another observation about the layers of possible symbolic meaning inherent in geometric constructions. Two circles that are drawn so that their peripheries cut through each others centres create a vesica. The vesica was in itself a symbol for the generative force, rebirth and transformation.

We have reason to believe that two circles combined in such a way among other things signified Heave and Earth as the Lord´s Dominion, the totality of creation. Chirst in Majesty on his heavenly throne is often depicted in a vesica shaped halo, sitting on the rainbow or an arc. From the two circles and the vesica several important forms can be derived. The vesica is naturally also the Fish, "ICHTUS" or (Iesous Christos Theou Uios Soter: Jeusus Christ God´s Son Saviour). That the vesica was seen as a symbol for generative power of the pregnant woman is not a new age fantasy. It is supported in medieval art. The Vesica is therefore a symbol for birth and resurrection and is also associated with the Virgin. A number of important symbols can be derived with the geometry of the square, circle and vesica. The underlying geometric structure is important for the form far beyond being a method to organise proportions in an aesthetically pleasing way. |

I had heard about the vesica "cut into two halves" would give an upper "heaven" and a lower "earth" (probably from you Peter when I think about it), but I had not considered the "ichtus" sign at all.

It is interesting that for a long time in the early church the symbol of Christianity (a religion demanding rebirth) was the fish.

The cross is first widely used in the 300's. Probably because of the myth of Constantine the Great's conversion by the "in hoc signo vinces" cross he saw in the sun (or actually in greek: /en toútōi níka/ )

The halo in Christian iconography is actually a solar disc. Constantine was a follower of Sol Invictus and possibly made his own personal syncretism of Sol Invictus and Christianity. His "Christian" belief might have been somewhat "original", as it possibly often is for adult converts of power, not used to being argued with.

The halos used in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople are not vesica shaped.

Theotokos (Mother of God with Christ baby) in the center and Justinian to the left and Constantine the Great to the right:

[ Linked Image ]

Source: http://static.panoramio.com/photos/large/68301122.jpg

The oldest Byzantine image of "Christos Pantokrator" (Christ as world ruler) has neither a vesica shaped halo.

From the Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai from ~565 AD.

[ Linked Image ]

So a "vesica shaped fish" was used by the very early church, but when the vesica was first used within the Christian iconography (halos etc) is unknown to me?

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| Mark, I cannot really express how wonderful it is to see you perform this analysis with results that are so parallel to what I have come across. Even more so because I have only published a small part of the material and have yet to describe many important details. You have not simply copied stuff or tried to force a square peg in a round hole. You show many of the same strategies I have found but in other swords and from your own conclusions.

|

Thanks for your very kind words Peter! This whole question of geometric design in swords and in medieval art in general is very interesting to me. My academic background is actually in mathematics, so a little rigorous geometry work does not discourage me. :D

| Niels Just Rasmussen wrote: |

| "Any element that is added to the structure must be defined by elements that already exist in the structure. A new geometric form must be constructed from well defined points that are already present. The diameter of a circle or the sides of and octagon cannot hover unrelated to the rest of the structure: they must be "grounded" in the existing grid." Another project for Mark, perhaps :lol: |

I have definitely tried to keep this principle in mind... each diagram feels like a puzzle to be solved. It's very satisfying when the connections and similarities start to appear and everything begins to feel more systematic and less ad-hoc.

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| This diagram might be helpful in explaining how the golden section can be performed in a square |

That definitely constructs a very elegant figure! It's very similar to the so-called Sacred Cut of the square:

[ Linked Image ]

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| The inscription "SctSPETRNnuS" on the other side is probably an invocation to Saint Peter, the protector of the Catholic Church. |

Just to expand on one very minor detail of this inscription, the sequence of letters "NN" seems to recur on a number of other swords... often with the letters in different scripts (particularly "Nn"). Here's one such example, and another where it appears on a finger ring. I think it's interesting that in all three cases, the sequence seems to immediately follow a name: Peter, Maurice (Mauricius), and Maria... all important saints. So it seems to me that this sequence has a use as a sort of concluding invocation in these inscriptions, possibly as an abbreviation of nomine nostri - referring to either the name of God, or an ungrammatical reference to the aforementioned saint...

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/607989

If I have time later today, I'll redo the diagram of the sword with the type N pommel and the 3:19 ratio, for better comparison with the others...

Here's the new version of the type N sword from L. Morat (in the Swiss National Museum in Zurich). I've tried combining elements of the Soborg and Brussels swords. The profile of the pommel appears like it may be less than a complete semi-circle... offsetting the 5:6 rectangle so that it aligns with the diameter of the pommel's circle instead of the pommel itself seems to give the best connections with the rest of the geometry. Coincidentally, this also makes the rectangle a near match in size for the rectangle of the larger Brussels sword... I don't have enough measurements to verify how closely the commensurate blade widths may coincide. If the photo can be trusted, the inscription on the blade is placed neatly within the third interlocking circle of the type II structure.

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

Mark, It is interesting to see what you do with the strategy of the arcs in the rectangle. In my analysis I have fund a number of different applications of arcs. One of these is the cut of the square according to the golden section shown previously.

I will take a closer look at how this method of projecting the long side of rectangles may play a role in the swords I have already made an analysis of.

So far, I have mostly made use of the cuts that can be generated in the basic square. By basic square I mean the square that has a side that is equal to the diameter of the first circle of the diagram. This circle is the first in a row or the large circle in a type I structure, that is further developed by a series of smaller circles with a diameter that equal the radius of the basic circle.

You can naturally also use the square and circle that are the "children" of the basic circle.

Involving further squares or rectangles that are derived from the basic structure, in series of subdivisions and cuts may compromise the precision of the construction. It could also make it more difficult to memorise and complicate its use in manufacture of the sword.

I think it is important to *always* keep the end of the pommel and the point of the sword in contact with each end of the basic lay out. -This is from the reason of the makers perspective. The geometry must be kept as simple as possible and it must be a simple affair to relate the sword that is being made back to the geometry.

The sword itself will therefore express a direct commensurability to the lay out. If the sword is put to hover inside the structure it is difficult to properly relate to the proportions of the geometric diagram during the process of manufacture. It makes it difficult to take direct dimensions for existing work and compare it to the ideal of the geometry.

When the sword in itself is directly commensurable to the underlying geometry it is also more powerfully expressing the idea of a wholeness of parts that combine into a meaningful creation. I think this matters.

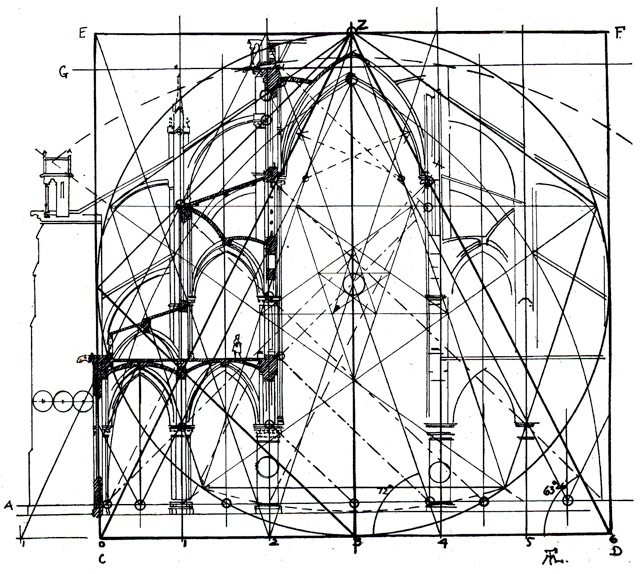

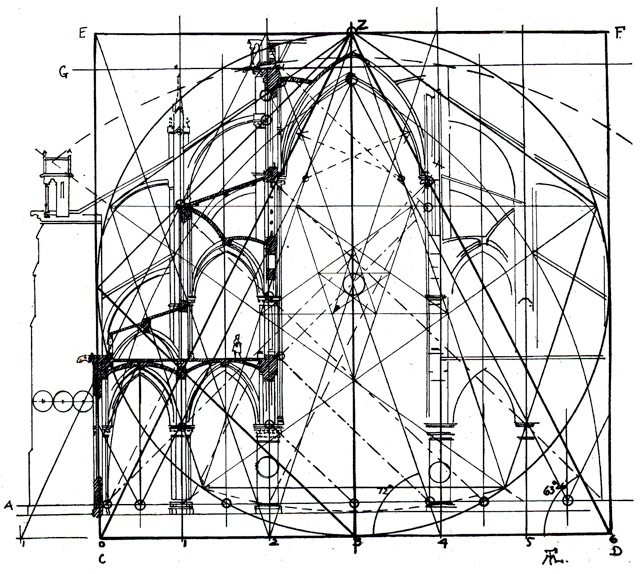

As an example of how geometric analysis can lead us astray, I keep an image of Macody Lund at hand. He was convinced that the pentagram was the basis for the proportions of the Notre Dame in Paris.

The way I see it, he worked really hard to force a square peg into a round hole.

The analysis he presented to prove this is so full of complicated solutions and multi layered steps that it should pretty clear to anyone that the solution is completely unrealistic. The strongest argument against the solution is however the fact that the poor builder has no way of correlating the building with the geometry, since important points are left hovering in empty space. The base of the square is situated a few meters under ground and many of the important crossing points are situated high up in the air between the vaults.

Those points that do correlate to the architecture do so at glancing angles that are very difficult to draw with a degree of exactness.

To me this is a parody of geometric analysis.

That is why I follow a set of simple rules that form a kind of hierarchy from the overall down through steps to the individual detail. The number of steps used to reach final solution also matters. The fever steps from overall to individual detail, the better. It limits the complexity of the construction and helps with precision in both drawing and manufacture.

-The complete length of the sword is always the same as the complete length of the basic geometric structure.

-The placing of the guard must be positioned in a way that is directly defined by the basic structure.

-All important elements of the design should refer back to the basic structure by a minimum of intervening steps, or directly from an already existing sub structure that is used to define another feature.

In addition to these rules we must also observe that:

-Any solution or strategy must make sense from the perspective of a maker.

-All elements of the geometry must be possible to construct using the simple drawing tools at hand during the period in question.

There exist a series of simple geometric cuts of the square that involves arcs that are constructed from corners and mid points. You can work with these and their tangent arcs and have a kind of a library of strategies.

Many of these cuts result in proportions that are harmonic or geometrically meaningful.

Dividing the square in diagonals is another effective way to generate powerful points and proportional ratios.

When working like this, I suspect you will find that it is not necessary to construct further squares or rectangles outside the structure that already exist.

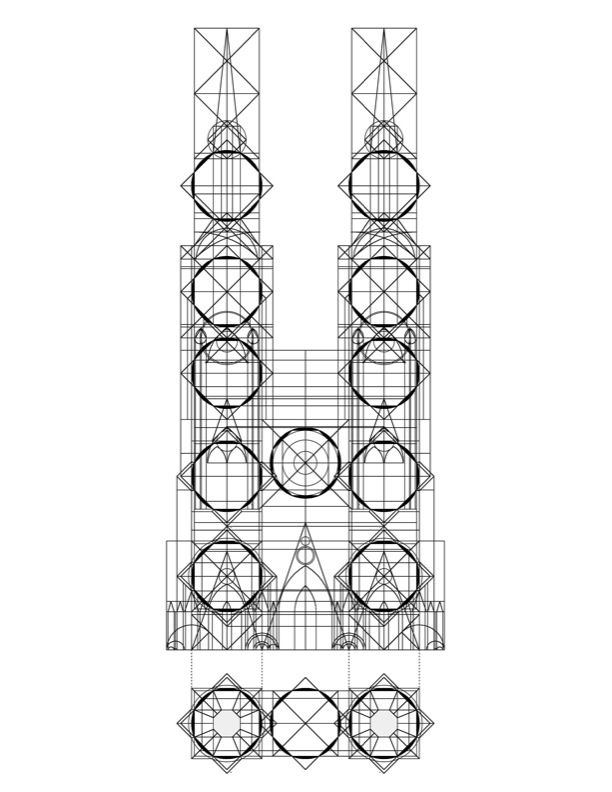

Naturally, I cannot know if this set of rules that I am following was in fact in use in the design of swords back in the day, but it is fully in accordance to what we can observe in surviving geometric plans for cathedrals and abbeys (from the work done by Robert Bork and others). By conforming to these rules, I am at least not inventing something that was not part of the medieval artisans knowledge and traditions.

Remember the words of the goldsmith Hanns Schmuttermeyer (in his book "Fialenbuchlein" from the end of the 15th century):

"Fundamenatally, this art is more freely and truly planted and developed out of the centre of the circle, together with its circumference, correct rules, points and setting out".

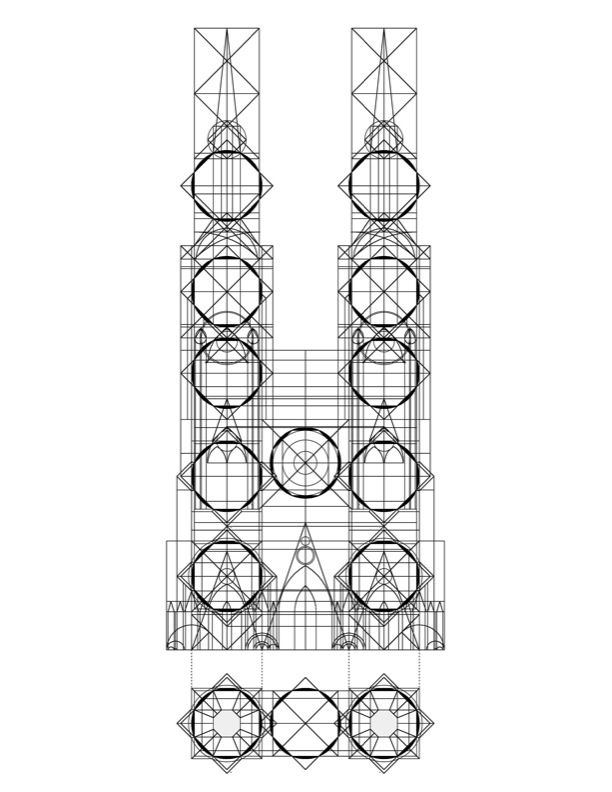

See below the fanciful and unrealistic geometry suggested by Fredrik Macody Lund and in contrast the coherent and commensurable geometry that forms the basis for the construction of the Strassbourg cathedral, revealed by Robert Bork from studying the pin pricks an scratch marks preserved in the parchment of the original medieval drawings.

Attachment: 167.92 KB

Attachment: 167.92 KB

The geometry of Notre Dame as suggested by Fredrik Macody Lund

Attachment: 93.22 KB

Attachment: 93.22 KB

The geometric armature of the Strassbourg cathedral as revealed by robert Bork from analysis of preserved drawings on parchment. Robert Bork based his analysis of scratch marks and pricks from the points of the compass.

I will take a closer look at how this method of projecting the long side of rectangles may play a role in the swords I have already made an analysis of.

So far, I have mostly made use of the cuts that can be generated in the basic square. By basic square I mean the square that has a side that is equal to the diameter of the first circle of the diagram. This circle is the first in a row or the large circle in a type I structure, that is further developed by a series of smaller circles with a diameter that equal the radius of the basic circle.

You can naturally also use the square and circle that are the "children" of the basic circle.

Involving further squares or rectangles that are derived from the basic structure, in series of subdivisions and cuts may compromise the precision of the construction. It could also make it more difficult to memorise and complicate its use in manufacture of the sword.

I think it is important to *always* keep the end of the pommel and the point of the sword in contact with each end of the basic lay out. -This is from the reason of the makers perspective. The geometry must be kept as simple as possible and it must be a simple affair to relate the sword that is being made back to the geometry.

The sword itself will therefore express a direct commensurability to the lay out. If the sword is put to hover inside the structure it is difficult to properly relate to the proportions of the geometric diagram during the process of manufacture. It makes it difficult to take direct dimensions for existing work and compare it to the ideal of the geometry.

When the sword in itself is directly commensurable to the underlying geometry it is also more powerfully expressing the idea of a wholeness of parts that combine into a meaningful creation. I think this matters.

As an example of how geometric analysis can lead us astray, I keep an image of Macody Lund at hand. He was convinced that the pentagram was the basis for the proportions of the Notre Dame in Paris.

The way I see it, he worked really hard to force a square peg into a round hole.

The analysis he presented to prove this is so full of complicated solutions and multi layered steps that it should pretty clear to anyone that the solution is completely unrealistic. The strongest argument against the solution is however the fact that the poor builder has no way of correlating the building with the geometry, since important points are left hovering in empty space. The base of the square is situated a few meters under ground and many of the important crossing points are situated high up in the air between the vaults.

Those points that do correlate to the architecture do so at glancing angles that are very difficult to draw with a degree of exactness.

To me this is a parody of geometric analysis.

That is why I follow a set of simple rules that form a kind of hierarchy from the overall down through steps to the individual detail. The number of steps used to reach final solution also matters. The fever steps from overall to individual detail, the better. It limits the complexity of the construction and helps with precision in both drawing and manufacture.

-The complete length of the sword is always the same as the complete length of the basic geometric structure.

-The placing of the guard must be positioned in a way that is directly defined by the basic structure.

-All important elements of the design should refer back to the basic structure by a minimum of intervening steps, or directly from an already existing sub structure that is used to define another feature.

In addition to these rules we must also observe that:

-Any solution or strategy must make sense from the perspective of a maker.

-All elements of the geometry must be possible to construct using the simple drawing tools at hand during the period in question.

There exist a series of simple geometric cuts of the square that involves arcs that are constructed from corners and mid points. You can work with these and their tangent arcs and have a kind of a library of strategies.

Many of these cuts result in proportions that are harmonic or geometrically meaningful.

Dividing the square in diagonals is another effective way to generate powerful points and proportional ratios.

When working like this, I suspect you will find that it is not necessary to construct further squares or rectangles outside the structure that already exist.

Naturally, I cannot know if this set of rules that I am following was in fact in use in the design of swords back in the day, but it is fully in accordance to what we can observe in surviving geometric plans for cathedrals and abbeys (from the work done by Robert Bork and others). By conforming to these rules, I am at least not inventing something that was not part of the medieval artisans knowledge and traditions.

Remember the words of the goldsmith Hanns Schmuttermeyer (in his book "Fialenbuchlein" from the end of the 15th century):

"Fundamenatally, this art is more freely and truly planted and developed out of the centre of the circle, together with its circumference, correct rules, points and setting out".

See below the fanciful and unrealistic geometry suggested by Fredrik Macody Lund and in contrast the coherent and commensurable geometry that forms the basis for the construction of the Strassbourg cathedral, revealed by Robert Bork from studying the pin pricks an scratch marks preserved in the parchment of the original medieval drawings.

The geometry of Notre Dame as suggested by Fredrik Macody Lund

The geometric armature of the Strassbourg cathedral as revealed by robert Bork from analysis of preserved drawings on parchment. Robert Bork based his analysis of scratch marks and pricks from the points of the compass.

Hi Peter,

You make excellent points, and Macody Lund is certainly a cautionary tale... The 5:6 rectangle is easily removed from the diagram of the Morat sword leaving the rest of the design that is essentially similar to the Soborg sword, which just goes to show that it was floating and not properly connected to the rest of the geometry. I was hesitant to share it, but I thought the coincidences that it had with various other details were interesting... :blush:

I'd be very pleased if this leads somewhere, but I have just realized that even for the Brussels sword the rectangle is probably not an essential constructive element... it's no more than an additional (and possibly approximate?) relationship generated from the underlying design. Whether or not it is accurate for the actual sword, I think my diagram can be most efficiently constructed as follows:

[ Linked Image ]

All this linework was present or implied in the previous diagram... the final small circle is the same as before, measuring very close to 1/5 of the cross. The rectangle and arcs can then be placed on top of this fundamental design to illustrate the additional relations... but I think it looks much better without it!

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

The photo of the Morat sword in my previous post is taken from Marko Aleksic's book Medieval Swords of Southeastern Europe. Something that may be worth considering is that Aleksic is quite confident that the type N pommel is not original with the rest of the sword. From p. 60 of the book:

I also noticed now that he mentions in passing the height of the pommel is 28 mm... my diagram predicted this to within 1 mm of accuracy. :)

You make excellent points, and Macody Lund is certainly a cautionary tale... The 5:6 rectangle is easily removed from the diagram of the Morat sword leaving the rest of the design that is essentially similar to the Soborg sword, which just goes to show that it was floating and not properly connected to the rest of the geometry. I was hesitant to share it, but I thought the coincidences that it had with various other details were interesting... :blush:

| Peter Johnsson wrote: |

| I will take a closer look at how this method of projecting the long side of rectangles may play a role in the swords I have already made an analysis of. |

I'd be very pleased if this leads somewhere, but I have just realized that even for the Brussels sword the rectangle is probably not an essential constructive element... it's no more than an additional (and possibly approximate?) relationship generated from the underlying design. Whether or not it is accurate for the actual sword, I think my diagram can be most efficiently constructed as follows:

[ Linked Image ]

All this linework was present or implied in the previous diagram... the final small circle is the same as before, measuring very close to 1/5 of the cross. The rectangle and arcs can then be placed on top of this fundamental design to illustrate the additional relations... but I think it looks much better without it!

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

The photo of the Morat sword in my previous post is taken from Marko Aleksic's book Medieval Swords of Southeastern Europe. Something that may be worth considering is that Aleksic is quite confident that the type N pommel is not original with the rest of the sword. From p. 60 of the book:

| Marko Aleksic wrote: |

| the Type Xa blade with inscription + INIOMINICII + suggests more extensive time interval, around the transition from the 11th to the 12th century and short hilt for one hand and short straight cross-guard are in accordance with that date. Nevertheless, it could be noticed on the photograph of this sword that pommel is made of different kind of iron and that it is of conspicuously darker color than other parts of the sword. It seems that this is rather good example how new pommel had been mounted on the sword used and retained for almost a century. |

I also noticed now that he mentions in passing the height of the pommel is 28 mm... my diagram predicted this to within 1 mm of accuracy. :)

The 1:1/√2 cut of the basic square may give the solution for the width of the blade and pommel of the Morat sword. :idea:

[ Linked Image ]

[ Linked Image ]

Page 3 of 9

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum