Renaissance Armies: The Scots

An article by George Gush

16th Century Scottish claymore swords

|

Like the Swiss, the Scots provided a steady flow of mercenaries to richer nations, serving with distinction, most notably in French, Dutch and Swedish armies, where they provided both complete regiments (including part of the French Royal Household) and many distinguished commanders. However, we are here concerned with actual Scottish armies of the period, and their service was confined to the British Isles. Like the Swiss, the Scots provided a steady flow of mercenaries to richer nations, serving with distinction, most notably in French, Dutch and Swedish armies, where they provided both complete regiments (including part of the French Royal Household) and many distinguished commanders. However, we are here concerned with actual Scottish armies of the period, and their service was confined to the British Isles.

In the 16th Century there was a continuous conflict of raid, counter-raid and minor battle on the Border, punctuated by the great clashes of Flodden (1514) and Pinkie (1547), both Scots defeats, plus internal conflict in the later part of the century, involving the expulsion of French forces with English aid. In the 17th Century the Scots played a notable part in the Civil Wars, raising both the grimly efficient armies of the Covenant, which fought in all three Kingdoms, and the dashing Royalist army of Montrose (in whom Scotland produced arguably the greatest general of the period).

The Lowland Pikemen

The spear was the traditional weapon of the Scots, suited to a poor land with little cash or metal to spare and dependent on an armed peasantry for defense; the solid blocks of spearmen or "schiltrons", which met the English on many a medieval battlefield, had a long history behind them, back possibly to the ancient Picts, who had also formed tight clumps of spearmen in battle.

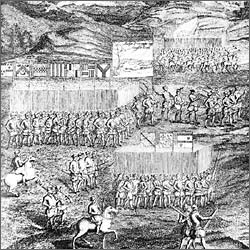

Carberry Hill. Forces of the (Scots) Confederate Lords. Note baronial banners, arquebusiers, and archers.

|

For the Flodden campaign, James IV replaced spears with imported "Swiss Pikes", 15 feet long, accompanied by 40 French captains to instruct the levies in Continental tactics. Scots pikemen formed shoulder to shoulder in columns at least as deep, and often deeper, than they were wide. In defense the front rank crouched so low that they almost knelt, with the pike-points of the rear ranks crossing those of the front, as easy to encounter as an "angrie Hedgehog". In attack they came on, at Flodden, "Almayne (German) fashion, very orderly and with no shouting", but it is reasonable to suppose that their levies, though very brave, were less well-drilled and disciplined than Swiss or German professionals.

Earlier they had been formed into units of about 500, and these may have remained, but the tactical columns were much larger: at Pinkie basically three huge "battles" which must have been at least 7,000 strong; at Flodden these were, perhaps with French advice, divided into about eight smaller columns, mostly around 5,000 strong.

Scots forces were based on a militia system not unlike that of England, Scots being obliged to equip themselves for war according to rank, and gentry to maintain feudal contingents, appearing for the Sheriff's inspection at biannual "Wappinshaws" (perhaps lured by the free drinks sometimes provided!). The weapons listed as acceptable at Wappinshaws of the 16th Century included spears and pikes, longbows, crossbows, two-handed swords, halberds, Leith axes and Jedwart Staves (the latter two were long, broad-bladed two-handed axes, similar to a halberd without its spike). Hand guns were also to be provided, and by 1535 landed men were ordered to equip themselves with an arquebus-a-croc, but at Pinkie the Scots had few firearms—in fact lack of missile power was a major weakness in their 16th Century armies.

Mid-century Scots pikemen mostly wore a simple iron helmet, a jack, and white doublet and hose, the sleeves and thighs of the latter being guarded against sword-cuts by four or five rows of brass chain. A large kerchief was wound three or four times round the neck, "Not for cold, but for cutting", and further protection was provided by a round buckler held in the left hand, even when grasping the pike; secondary weapons were broadsword and dagger. Lowlanders of the 16th Century commonly wore the "blue bonnet", and other usual clothing colors were grey and light blue.

Pikemen formed 70 percent or more of Scottish armies at the larger battles of the period.

a. 17th Century Highland mercenary with arquebus. Wears bonnet, baggy trews and a coat. Note short, broad single-edged sword. b. 16th Century Highlander with "skull", bow, targe and claymore, wearing leine. c. 16th Century Scots pikeman in jack. Note chain protection and shield, d. Mid-17th Century Highland chief. Belted plaid. Closely resembles later Highland costume, e. Highland archer in belted plaid and blue bonnet, 1630s. f. 16th Century Highlander. He has stripped to his shirt which he has tucked up and knotted round his waist. His equipment includes a conical helmet of "Celtic" type, which could probably still be worn in the early 16th Century; a spiked targe; and a Lochaber axe (note hook for cutting reins, etc).

The Highlanders

All Highlanders were warriors, following their chiefs to battle, and in the 16th Century still roused by the sending round of the "fiery cross" summoning them to the traditional mustering-place. They were found in all Scottish armies of the period; usually 15 percent of the larger ones.

Their arms, even in the 17th Century, were, firstly, the bow: Highland archers in Leslie's army in 1644 were said to be able "To kill a Deere in his Speed" and there is no reason to believe English strictures on Scottish shooting; secondly the claymore, which throughout our period was a two-handed sword. A dirk and a flat round "targe", usually leather-covered and decorated with embossing and metal nails and boss, sometimes spiked, would also be carried.

In the 17th Century, basket-hilted broadswords began to replace the original claymore, and firearms began to spread among the Highlanders. A roll of Athollmen in three parishes in 1638 shows the proportions of weapons available: 523 men had 110 "guns" and two "hagbuts" to 149 bows. There were also 11 pistols (probably the characteristic Scottish all-steel pistol with fishtail butt), 11 long axes and halberds. There were 448 'swords' to only three two-handed swords.

Only 11 men had helmets and mail shirts (perhaps indicating 11 with "Gallowglass" type equipment) but 125 had targes.

In the 16th Century the Highlanders, if not equipped with a helmet, would be bareheaded, but in the 17th Century they adopted the blue bonnet from the Lowlanders. Basic costume also changed around the turn of the century; 16th Century Highland dress consisted of the "leine croich", a linen knee-length shirt, usually dyed yellow with saffron, and worn with a voluminous mantle or plaid secured with a brooch. After 1600 the leine disappeared and was replaced with the belted plaid' which gave the appearance of the later kilt and plaid. Stockings were also adopted for the first time, footwear remaining slashed rawhide brogues.

In both centuries short coats and trews could also be worn, the latter being in the 16th Century sometimes knee-length, in the 17th sometimes baggy to the knee.

The only protection commonly worn by 16th Century Highlanders was a tar-stiffened leine covered with deerskin, but in any case they often stripped for battle, though sometimes retaining the shirt, the sides of which were tucked into the belt, the resultant "tails" at front and rear being tied between the legs; an Englishman described some in 1640 as the "nakedest fellows I ever saw", and they were on parade.

Up to the 16th Century, a chief might wear a padded quilted coat called a "cotun".

Plaids, often trews, and sometimes jackets were checkered, striped or parti-colored, frequently in early tartan patterns which were simple and with a large "set". As yet they did not identify clans, and a simple black and red Rob Roy style seems to have been popular. Other colors favored were purple, blue and brown.

Highlanders were ferocious but unreliable, relying either on skirmishing or a single volley followed by a wild charge; they hated, and would not stand up to, cannon, which they called "the mother of muskets".

The Cavalry

Guidon of David Boswell of Baimuto, captured at Pinkie.

|

A very small component of most Scots armies, at least in the 16th Century (about five percent at Pinkie). Even in the 17th Century the Scots suffered by being lightly-mounted on small, "scrubby nags" better suited to Border skirmishes than a stand-up fight. Wappinshaws suggest that the ordinary gentry would wear corselet, jack or brigantine, bascinet helmet, gorget, "splints" for arms and upper legs, and mail hand and knee protection. Great nobles could have full plate armour though even King James IV is mentioned as clad in a sallet with hauberk and jack under his silk emblazoned surcoat. Basic weapon would be the lance but at both the great 16th Century battles the King and nobles dismounted and fought in the front rank of the pike columns (incidentally rendering them practically invulnerable to English archery).

Usually the chief mounted troops of Scots armies were "Border Horse" armed with light lance, sword, and, by 1600, one pistol, with "steel bonnet"—often covered by a cap—and corselet, mail or jack as protection; leather breeches and boots. They were distinguishable, if at all, from their English counterparts only by checkered plaids and the saltire of St. Andrew on breast and back.

The Artillery

Usually a strong point with Scots armies, though not always very effectively used. The train as ordered for the Pinkie campaign was of: two Cannon, one Culverin Bastard, two other Culverins, one Pas Volant; and for Flodden: five Cannon, two Culverins, four Culverin Pykmayne and six Culverin Moyane.

Scottish cannon were nearly all brass, and largely ox-drawn, a cannon needing a team of 36, Culverin Pykmayne 16 and a horse, Culverin Moyane eight and a horse. The Pinkie train was of 500 men including pioneers, a drummer and their own standard-bearer.

The Scots were also fond of "battery" guns with multiple barrels on a single carriage, possibly to compensate for lack of infantry firepower; as early as 1522 they had "1,000 hagbushes carted upon trestles" and at Pinkie planned to use "20 brass pieces on little carts".

17th Century Covenant Armies

The force sent under the Earl of Leven to aid Parliament in the Civil War consisted of the following units:

Infantry

| Regiment | Colonel |

| Kyle and Carrick | Earl of Cassillis |

| Galloway | William Stewart |

| Fife | Earl of Crawford-Lindsay |

| East Lothian | East Lothian |

| Strathearn | Lord Coupar |

| Loudon-Glasgow | Earl of Loudon |

| Midlothian | Lord Maitland |

| The Merse | Sir David Home |

| Stirlingshire | Lord Livingston |

| Tweeddale | Earl of Buccleuch |

| Edinburgh | James Rae |

| Fife | Earl of Dunfermline |

| Clydesdale | Sir Alexander Hamilton |

| Perthshire | Lord Murray of Gask |

| Teviotdale | Earl of Lothian |

| Nithsdale and Annandale | Douglas Kilhead |

| Angus | Viscount Dudhope |

| Linlithgow and Tweeddale | Master of Yester |

| Mearns and Aberdeen | The Earl Marischal |

| The Ministers' Regiment | Arthur Erskine |

The Levied, or College of

Justice Regt | Lord Sinclair |

Only two or three of these Colonels had military experience, but nearly all the Lt-Cols had) |

Cavalry

| Colonels |

| Leven (C-in-C) |

| Leslie (Maj-Gen Sir David) |

| Earl of Eglington |

| Earl of Dalhousie |

| Lord Gordon (troop) |

| Lord Kirkudbright |

| Earl of Balcarres |

| Marquess of Argyll's Troop |

| Michael Weldon |

Dragoons

| Col Hugh Frazer (4 companies) |

The infantry were raised from all those eligible to serve, between the ages of 16 and 60. They were predominantly pikemen and musketeers, in the proportion of 2:3. However, those who could not be equipped with musket or pike were ordered to have halberd, Lochaber axe or Jedwart stave, and there were also some Highland archers in native dress. Lowland infantry would appear similar to English troops of the period, though some probably wore bonnets. The regiments were not generally uniformed though the Mearns and Aberdeen men were probably redcoats, as were those of at least one of the six Covenanting Regiments serving in Ireland over this period (Col Hume's). Pikemen are said to have lacked armour, but probably had jacks or buff-coats.

By 1644 regiments had from five to ten companies and the stronger ones were of about 450-500 men.

Carberry Hill (1560s). Mary Queen of Scots' troops, with royal and national standards, and artillery. (National Army Museum)

|

The cavalry had helmets and sleeveless buff-coats (though jacks were also permitted) and were supposed to carry either pistols and broadsword, or light lance, the latter being apparently carried by a great many, including the Commander-in-Chief's own regiment. Lances were somewhat anachronistic by this time, but seemingly effective, breaking a Royalist foot regiment at Marston Moor and causing some trouble to the Ironsides at Dunbar.

The regiments of Horse were supposed to be of eight 60 man Troops (the C-in-C's of ten).

A Scots trooper of the Bishops' Wars was said to be equipped with "fyve schot at the least, quhairof he had ane carrabin in his hand, two pistollis be his sydis, and uther tva at his sadill torr", but in general Scots cavalry seem to have had fewer pistols among them than the English.

As usual there was a strong train of artillery, which in 1644 had: six Demicannon, oneCul-verin, three Quarter cannon, 54 Demiculverin, three Irort pieces and 88 "Frames" (these were very light guns for infantry support, the brainchildren of the famous Scots artillerist "Sandy" Hamilton, who had served Gustavus Adolphus. He had invented an ultra-light 12 pounder gun, three feet long, which could be carried by one horse, and also some kind of multi-barrel infantry support weapon on a wheel-barrow-like mounting. The "frames" could well be these, or light field pieces like those used by Gustavus; their number makes it seem likely that about four were attached to each infantry regiment.).

A second army of nine infantry regiments and three Regiments and nine Troops of Horse was dispatched in 1644, and in 1647 the Scots recast their forces into a "New Modelled Army" of seven Infantry Regiments, each of 800 men in six companies, 15 Troops of Cavalry (80 each), and two 100 man companies of Dragoons.

Montrose's Army

Montrose won five victories for the King over greatly superior Covenant forces (they were second-line, most of the best troops being in England), with a tiny and improvised force never over 3,000 strong. The heart of his force was an "Irish Brigade" of three regiments about 1,100-1,500 strong in all, under the giant Alastair MacDonald (Colkitto). "Irish" was also used to describe West Highland Scots in this period and the Brigade was probably a mixture; they seem to have been mainly experienced soldiers, presumably from the European wars.

Primarily musketeers, they used the new three rank deep volley-firing tactics, but also acquired sword and targe and could follow their volley with a devastating charge; against cavalry they compensated for their lack of pikes by opening ranks and letting the horsemen through, then firing into them as they passed. They wore bonnet, coat and trews, as did Montrose himself, who carried sword, shield and half-pike.

The rest of the army consisted of highlanders with traditional dress and weapons (though they probably obtained firearms, etc, from the defeated enemy), and about 300 Gordon Horse, who were armed with pistols. Artillery from one to nine pieces according to captures and transport difficulties.

Flags

The national flag in use long before this time was the "auId blue blanket" with the white saltire of St. Andrew; Scots 16th Century armies would also display the banners and guidons of the nobility, some of which are shown. At Pinkie, one Scots flag bore the Church personified, kneeling before Christ, and the motto Ne Obliviscaris Domine Sponsae Afflictae.

The Royal banner—yellow with a red lion and red trellised border, would be flown by the King, but could also be used by his Lieutenants, such as Montrose.

In Montrose's separate and doomed campaign of 1650, his own flag was white, showing a lion about to leap a river between two rocks, and the motto Nil Medium. The horse and foot had black flags, bearing respectively three pairs of clasped hands holding swords and the motto Quos Pietas Virtus et Honor fecit Amicos, and the severed head of Charles I with the motto Deo et Victricibus Armis.

Some clans would have their own symbols, derived from leaders' badges, or like the bunch of heather on a spear still carried by the MacDonalds in this period.

About the Author

George Gush was educated at Tonbridge School, Kent, and won an Open Scholarship in History to Christ Church, Oxford, and has pursued a teaching career ever since graduation.

Acknowledgements

Article contents originally © Copyright George Gush and Patrick Stephens, Ltd 1975, 1982 and reproduced here with permission.

|

|